Africa and the European Union: Summit Number Four

EU-Africa Summit, April 2, 2014

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D. (Hist.), Senior Research Fellow, Research Fellow of the Center for Development and Security Studies, Faculty of World Politics, Moscow State University

With the 4th EU-Africa Summit just finishing in Brussels, the time is ripe for an analysis of the key problems within the partnership as well as for coming up with ideas about how they might be resolved. Here we take a look at political dynamics in African states and the relationships these countries hold with other actors (such as the BRICS countries), as well as examine how current trends in international relations might affect cooperation with the European Union.

With the 4th EU-Africa Summit just finishing in Brussels, the time is ripe for an analysis of the key problems within the partnership as well as for coming up with ideas about how they might be resolved. Here we take a look at political dynamics in African states and the relationships these countries hold with other actors (such as the BRICS countries), as well as examine how current trends in international relations might affect cooperation with the European Union.

EU’s Foreign Policy towards Africa

Africa ranks high among European international priorities.

The first EU-Africa Summit took place in 2000 in Cairo with the second one following in 2007 in Lisbon. There the Joint Africa-EU Strategy and the first 2008-2010 Action Plan for its implementation were signed, effectively launching the process of building the world’s most advanced and sophisticated form of interregional relations.

In 2010, Tripoli hosted a third summit, where a second Action Plan was adopted to cover the 2011-2013 period.

The fourth EU-Africa Summit, devoted to "Investing in People, Prosperity and Peace", was held on April 2-3 in Brussels, with several additional events also organized in its run-up.

Any discussion of the background to EU-Africa relations must touch upon, on the one hand, unprecedented economic growth in many African countries, burgeoning markets, and exciting mining prospects, while on the other hand, European responses to the aftermath of the financial crisis, sequestered budgets and growing Euroscepticism. Brussels has acknowledged the need for a review of its development assistance strategy in order to achieve better results at lower costs. Nevertheless, the 11th budget of the European Development Fund for 2014-2020, the main EU financial source for some African states under the Cotonou Agreement, is now 31.6 billion euro, markedly surpassing the previous 10th budget of 22.7 billion euro.

In fact, the absence of a trouble-free environment is a result of many changes in the world over the past several years as well as many new and serious problems that are currently overshadowing the relationship.

Due to internal political changes, Egypt and Libya are no longer at the forefront of African regional structures and pan-continental development projects. Cairo and Tripoli used to be key African Union donors and the engines for the continent’s engagement with the EU; their internal weaknesses are contributing to a slowdown in the development of the intercontinental partnership.

Cairo and Tripoli used to be key African Union donors and the engines for the continent’s engagement with the EU; their internal weaknesses are contributing to a slowdown in the development of the intercontinental partnership.

In particular, current differences between African countries and the European Union include disagreements over inquiries made by the International Criminal Court towards African politicians and EU talks on economic partnership with several African states. The Europeans and Americans have been also angered by recent Nigerian and Ugandan laws targeted against LGBT communities [1].

Another significant format for cooperation has run through the Cotonou Agreement of 2000 between the EU and 79 states of Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific, i.e. the ACP Group [2]. Under this multilateral framework, Brussels began signing Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) in 2007 with individual African states and regional associations. As has been stated previously, these arrangements have become a major roadblock on the development of the European-African relationship, since they have a clear EU bias and hence threaten African economies [3]. The Cotonou Agreement lays out a phased transition towards a new trade regime between the European Union and the ACP Group that would eventually build a system based on mutuality rather than on unilateral preferences (the format was chosen under the pretext that such preferences contradict WTO rules [4]). The EPAs are supposed to assist European firms in entering African markets. AU-EU talks on economic partnership agreements stumbled on the point in the European proposal that pushed for free trade arrangements. Due to differing levels of economic development, this type of bilateral economic relationship would definitely harm Africa.

Discussions over the EPAs began in 2002 and African states were supposed to adopt them by 2007, so that the arrangements could enter into force by early 2008. But by 2007, most African states had rejected the agreements.

By September 2013, the agreements were signed or initialed by only 16 out of the 48 sub-Saharan states [5]. Without progress during the talks over the previous twelve years, Brussels set an October 1, 2014 deadline, before which African states are supposed to either ratify interim or sign permanent EPAs and begin their implementation, or to export their goods to the EU under a less beneficial scheme, i.e. the General System of Preferences. Such pressure on the part of Europe is unquestionably fraught with the possibility of worsened relations with Africa, since the EPAs carry both economic and political overtones.

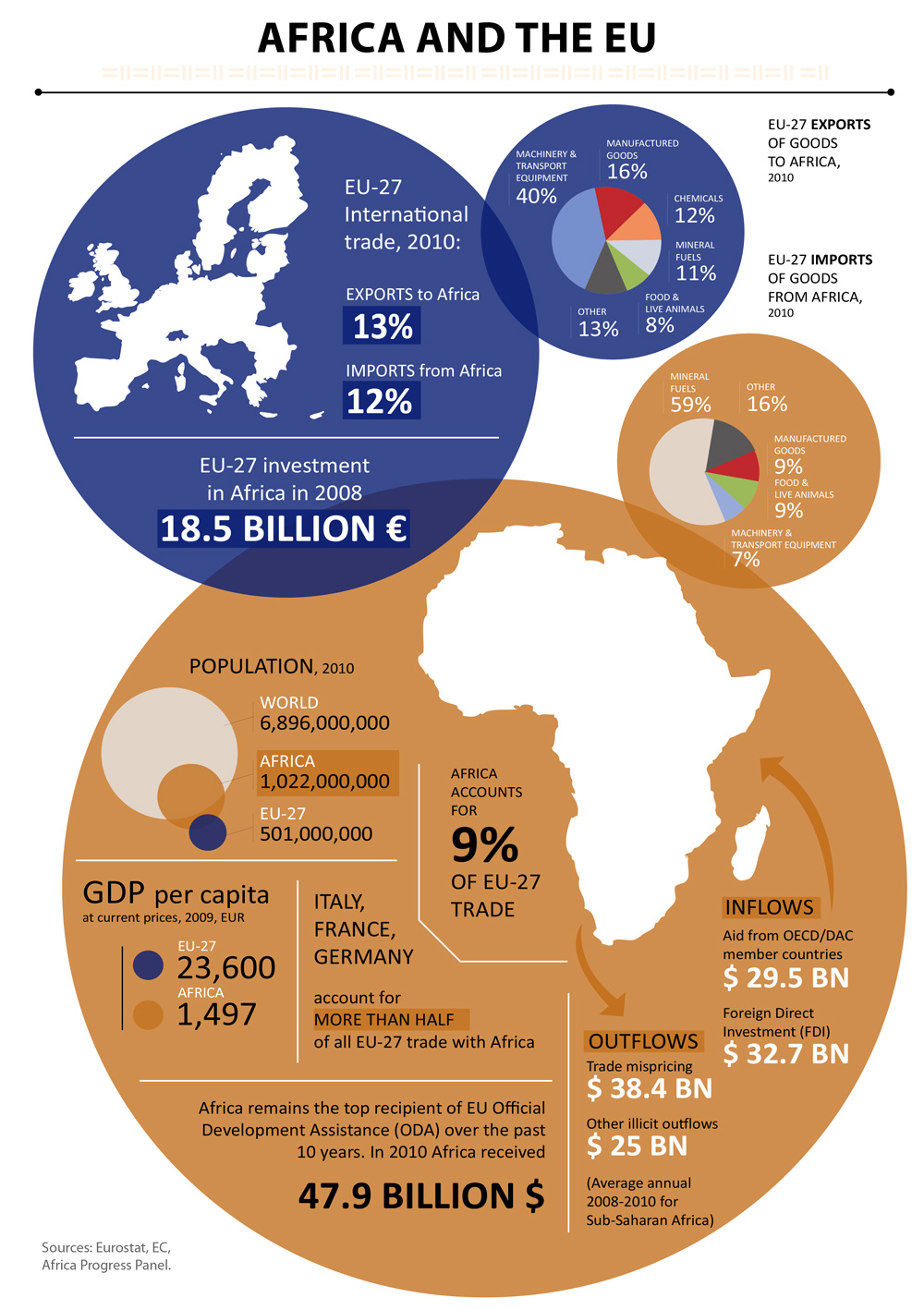

According to the European Commission data, EU trade with Africa in 2012 reached about 338 billion euro. Estimates by Renaissance Capital investors, who operate mostly in developing markets, show that the EU accounts for only 25 percent of the sub-Saharan states’ trade. In 2012, imports from the EU-28 made up just 15 percent of the total for Africa and exports held at 13 percent [6], in contrast to Asia was responsible for 56 percent of imports and 47 percent of exports. In 2011, European FDI in Africa reached 73 billion euro.

AU-EU talks on economic partnership agreements stumbled on the point in the European proposal that pushed for free trade arrangements. Due to differing levels of economic development, this type of bilateral economic relationship would definitely harm Africa.

Africa's hydrocarbon reserves are attracting the European Union as a means to bolster its economic security, crude oil being the key African import item for the EU-28. In fact, since 2005, Africa has been EU's second largest oil supplier (139 million tons in 2012, with Nigeria and Libya in the lead) [6].

According to the OECD, the European Union allocated 25.3 billion euro to Africa in aid in 2011, more than a half of the total international assistance furnished to the continent. In December 2011, a proposal was made to the so-called Pan-African Program with a 1 billion euro budget included in the Development Cooperation Instrument and designed to assist developing countries, including ones in Africa, by providing additional financing for the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (the program's implementation began on January 1, 2013, totaling 845 million euro as of the time of writing.

Why Africa is Important for the EU

Africa is of significance for the European Union in many areas, since the two continents are bound by a most complicated common history.

For Europe, bilateral cooperation is definitely strategic. Apart from trade and energy, the full scope includes political, commercial, cultural and scientific ties, as well as security and regulation of migratory flows. The EU's most developed partnerships are currently with the SAR, Nigeria, Cote d'Ivoire, and Northern African countries.

In Africa, investors, are not confining themselves to mineral extraction, but instead are displaying an increasing interest in infrastructure, ICT, manufacturing, processing, agriculture and services.

In late January 2014, an agreement was reached to sign an economic partnership agreement between the European Union and the Economic Community of West African States, the first regional partnership arrangement on a new foundation since 2007.

Notably, former metropolitan countries, for example Great Britain and France, tend to interact more closely with their former colonies.

African states are quite important in the Commonwealth and collectively visible in the United Nations and other international forums. Since the two continents neighbor each other, conflicts and political unrest in Africa may generate torrents of migrants and refugees, a major potential headache for Europe.

Africa is also facing a rush of investment. According to Ernst&Young, the number of the FDI projects in 2007-2012 in sub-Saharan Africa has been annually growing by 22 percent. Over the last few years, FDI from industrialized countries to Africa has been on the downturn [7], while FDI from developing states has been stable.

In Africa, investors, both from Europe and the BRICS, are not confining themselves to mineral extraction, but instead are displaying an increasing interest in infrastructure, ICT, manufacturing, processing, agriculture and services. In reality, sub-Saharan Africa (with the exception of South Sudan) is booming, with economic growth in 2013 of 5.7 percent. African oil exporters could boast even higher figures, while the world's average was just 3.3 percent.

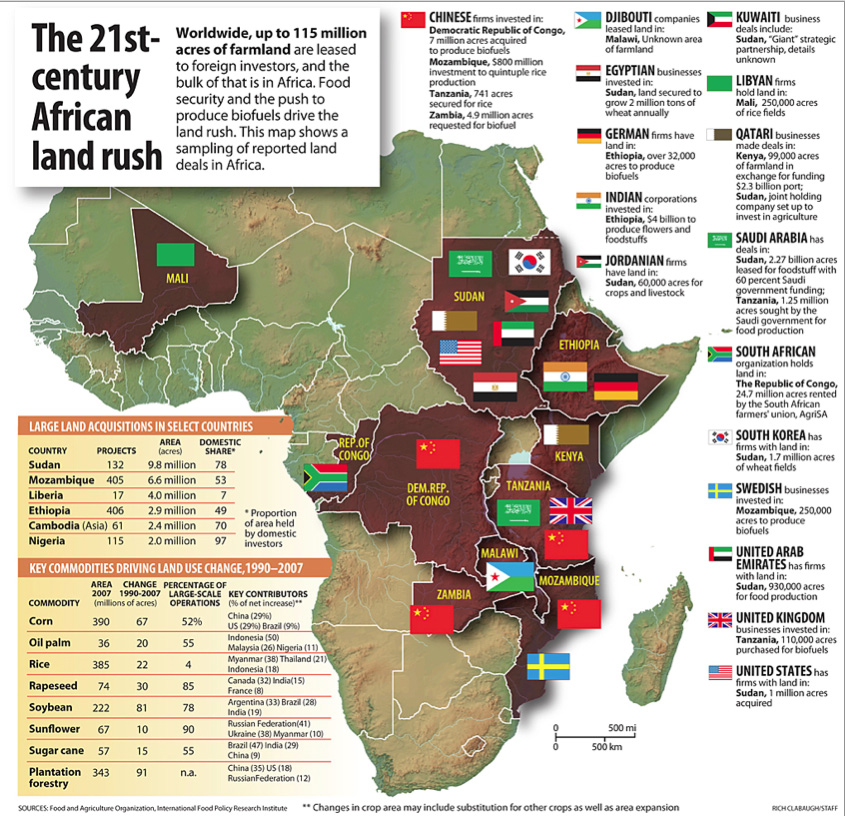

Africa is ready to plunge into the green revolution, its first stage seen in the ongoing fever for land acquisition. Foreign corporations and governments are buying and leasing huge areas to grow crops for food and biofuel production [8] (See Map 1).

BRICS countries are also moving into Africa with vigor. From 2000 to 2011, their share of African commodities exports grew from 10 to 24 percent, i.e. from USD 11.4 to 117.6 billion [9], with up to 70 percent of infrastructural projects in Africa implemented thanks to investment from these countries [10]. The BRICS grouping is doing its bit to accomplish the Millennium Goals of fighting poverty and increasing food security by developing African agriculture, as well assisting in conflict resolution and ensuring access to advanced technologies through programs for technological and scientific cooperation. The efforts of the BRICS countries within their association and in the G20 are having a marked effect on international negotiations and the EU's ability to defend its interests.

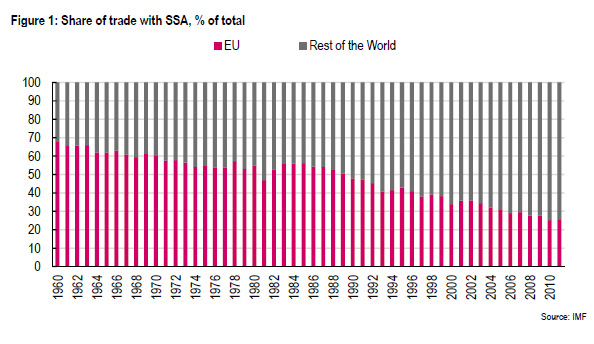

According to Pew Research, international attitudes towards the European Union in 2010-2011, including those of the BRICS and some African states (Kenya, Egypt, etc.), plummeted, as many now perceive Europe as a neocolonial entity. In its 2012 report "Sub-Saharan Africa: Export Trends – Changing Trade Dependencies", Renaissance Capital uncovered an astonishing trend: while the European Union remains Africa's largest trade partner as a supranational association, trade between the EU and sub-Saharan countries is at its historical low.

No matter how large it becomes, European assistance can never remove the underlying causes for conflict in Africa.

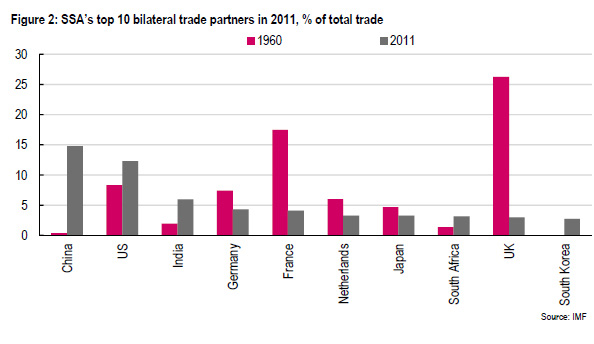

Whereas in 1960, the European Union accounted for two-thirds of sub-Saharan total trade, in 2011 its share was just a quarter, the same level as Africa’s trade with the developing countries of Asia. During the same period, the Chinese share went up to 15 percent.

The joint African-European strategy and the resultant partnership have basically been designed to overcome the donor-recipient paradigm and the challenges the EU has faced in connection with Chinese and Indian inroads into Africa. The signing of the Joint Africa-EU Strategy in 2007 was far from accidental, since in 2006, the China-Africa summit took place with the participation of 48 African heads of state and governments. Soon after in April 2008, the first India-Africa summit was held.

The underlying choice between the Chinese and European models of cooperation, which Africa is supposed to make, is a lasting source of African-European frictions.

Are European Investments in Africa Paying Off?

The EU is investing prolifically in Africa’s development and stability, while the recent conflict in Central African Republic has again required European involvement. Why should Europe help Africa? Does it really bring benefits? And when will Africans learn to deal with their own problems?

Nowadays, Africans may choose between Chinese and Western providers of services and technologies, investors and lenders.

First of all, since the 1990s, the number of wars in Africa dropped in half.

In fact, African conflict potential depends on several objective triggers, i.e. skyrocketing populations, deteriorating climate and environmental quality, poverty, a lack of democracy, etc. No matter how large it becomes, European assistance can never remove the underlying causes for conflict in Africa.

At the same time, there are also factors that are beneficial for conflict prevention and resolution, among them high growth rates, stable political systems in many states, etc.

Over the last 20 years, thanks to the peacemaking efforts of international and continental actors, Africa has become much more stable. Brussels is doing much to improve the African peace and security architecture, among other things through the establishment of the African Peace Facility in 2004 and support given to the African Standby Force.

The West did not hesitate to respond to the outbreak of interreligious violence in the Central African Republic after the regime change in 2013, with French and African peacemakers already deployed in the country. In February 2014, the European Union made the decision to send a 800-1,000-strong peacekeeping contingent there, but failed to do so as some European countries were unwilling to provide troops and hardware.

What Africa Means for Russia, China and the United States

The rise of Chinese influence in Africa has become a most noticeable global trend in the 2000s, as China has become the largest partner of sub-Saharan countries in bilateral trade after ousting U.S.A. from that position in 2009.

The African niche in China's foreign policy appears to be more significant than that of the EU's international efforts. The PRC regards Africa primarily as the source for minerals vital to its intensive economic development and as a market for industrial goods and large investment.

Beijing is trying to engage Africa into building the multipolar world that would respect the sovereignty and values of non-Western states. African-Chinese cooperation is genuinely comprehensive, as the sides are working together to advance African infrastructure, healthcare, education, farming and energy generation, as well as to tackle conflicts and many other problems. Moreover, China is also applying soft power by establishing cultural and scientific ties, making investments and building centers of trade, which means both reaching immediate goals and wielding long-term influence to shape a pro-Chinese predisposition among future African elites. Although Africans do not appear entirely happy about Chinese actions [11], they do understand that the benefits are huge and admit the importance of the Chinese experience and development model.

Engagement with China is also expanding Africa's room for strategic maneuver in world politics, which seems to be a major benefit from their bilateral cooperation. Nowadays, Africans may choose between Chinese and Western providers of services and technologies, investors and lenders. In the long term, judicious balancing in global politics may bring Africa even more dividends.

As for Russia, in the 2000s, Moscow raised Africa back among its foreign policy priorities, with greater interest among Russian businesses and more visits of Russian leaders to African countries.

In 2000-2012, Russia-Africa trade increased by seven and a half times, i.e. from USD 1.6 to 12.17 billion (by ten times with North African and by 4.8 times with sub-Saharan countries) [12]. Russia maintains military-technical cooperation with 20 African countries, which offer important markets for Russian heavy weaponry. In 2012, Russian arms exports to Africa were worth USD 980 million, i.e. seven percent of total exports and 20-25 percent of the African weapons market [13]. However, Russia's overall trading figures are far behind Chinese and European levels.

The key for developing the Russia-Africa relationship seems to lie in investments. According to Russian businesses operating in Africa, in mid-2012 Russian FDI in Africa amounted to USD 8.5-9.0 billion [14], with a 2013-2020 planned target of USD 17 billion [14].

Up to 80 percent of Russian investments in Africa are related to mineral exploration and extraction, and most of the sums are being channeled to Algeria, Angola, Nigeria and South Africa. In the last several years, investors have been increasingly attracted to East and Central Africa, i.e. Zimbabwe, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda; the most active companies have been LUKOIL, Severstal, Renova, RUSAL, Evraz and Gazprom.

African minerals are definitely attractive for Russia, which may see a depletion in its own thirteen currently viable items by 2018 [15]. Since the exploration and development of its own domestic resources are incredibly expensive, it appears to be more profitable and simple to import them from Africa. Russian banks are also on the move in Africa. In addition, significant opportunities also exist in ICT, outer space, financial services, nuclear energy, etc.

Africa also occupies an important spot in U.S. foreign policy. In June 2012, the White House issued an Executive Order on U.S. Strategy toward Sub-Saharan Africa focused on bolstering democratic institutions, encouraging economic growth, trade and investments, strengthening peace and security, and assisting in generating new opportunities and development. The U.S.-African economic and trade partnership is based on the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which provides palpable trade preferences to African countries complying with certain political and economic conditions. Washington plans to expand the Act, which has already helped increase African trade; as in 2011 the United States became Africa's third largest trading partner after the European Union and China.

The U.S.A. is worried by the growing clout of new actors on the continent and is working to counteract the process for protection of its own interests [16], among other things through its African Command set up in October 2008. This has been designed to assist African countries and organizations in building up their defense capabilities, as well as to alleviate threats to American regional interests.

* * *

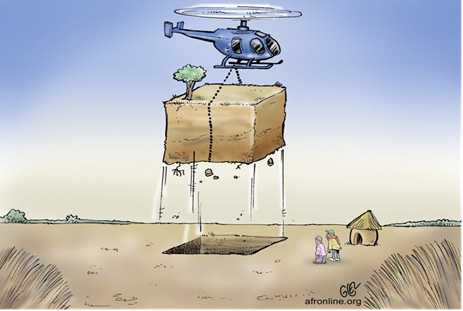

Africa is still in need of external assistance, but in the not-so-distant future it may hopefully be able to guarantee its own stability and prosperity. Africans are eager to take over responsibility for resolving problems of their states and communities [17]. The heart of the matter seems to be with regards to the search for fresh and smarter ways for foreign assistance, so that African countries could break free. The potential harm of aid has been amply described by Dambisa Moyo, a female Zambian economist, in her highly debated bestseller Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa [18] that clearly shows that Africa is willing to discover the roots of its problems and learn to tackle them on its own.

The West has to revise its aid efforts because of the consequences of the financial crisis and the challenges emanating from the BRICS countries, who are offering substantially different development assistance terms and obtaining better results. This has made Brussels question potential consequences [19].

In conclusion, it seems appropriate to underline that for fruitful cooperation to occur between the EU and Africa, adequate responses need to be found to numerous challenges. The two sides also need to continue discussing mutual expectations that have been previously neglected, reconsidering the role of Europe in Africa in view of the growing activity of Asian players. As far as Africa is concerned, now is the right time to use the favorable global environment for handling its numerous domestic troubles.

The two sides still have to go a long way to go; they need to critically assess difficulties uncovered by implementation of the Joint Strategy and find innovative ways for refreshing the pattern of cooperation. The Africa of today needs not so much aid as investment, new knowledge and technologies, and equal partnership.

The European Union is interested in generating a new framework for cooperation, since Africa has a no-nonsense geopolitical choice of potential partners and mentors in global politics. The financial crisis notwithstanding, the EU appears eager to strengthen cooperation with Africa. The new battle for Africa is gaining momentum and sluggishness might bring Brussels a strategic setback with long-term consequences. In addition, forecasts insist [20] that by 2020, European aid to Africa will pay back in spades.

1. On January 7, 2014, Nigerian President Jonathan Goodluck signed the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, enforcing criminal prosecution of same-sex relationships which had never been legal either in Nigeria or in Uganda. The new legislation is much more severe; the Ugandan version is also eliciting international condemnation.

2. Kaveshnikov N.Yu. The EU Relationship with Countries of Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific // European Integration. A Textbook / Ed. by O.V. Butorina. Moscow: Delovaya Literatura Publishers, 2011. P. 457.

3. The African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Group and the European Union (EU). Policy Research Seminar Report. Cape Town, January 2014. P. 18.

4. Stocchetti M. The Development Dimension or Disillusion? The EU’s Development Policy Goals and the Economic Partnership Agreements // The Nordic Africa Institute Policy Note. Trade. № 1. October 2007. P. 1.

5. The 16 countries include Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, the Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

6. The European Union and the African Union: A Statistical Portrait // Eurostat Statistical Books. 2013 Edition. Luxembourg, 2013. P. 14.

7. In 2010-2011, investment from the OECD, which incorporates most EU countries, in Africa fell from USD 33 billion to USD 21.9 billion (http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/outlook/financial_flows/an-in-depth-look-at-each-of-the-finance-sources/). According to Ernst&Young, FDI from industrialized countries have dropped by 20 percent. Despite an increase in the number of projects financed by British FDI at a rate of nine percent, investment from the United States and France and others in the industrialized countries group have dropped dramatically. At the same time in 2012, investments from developing market economies in Africa have risen for three consecutive years (http://www.ey.com/RU/ru/Newsroom/News-releases/Press-Release---2013-05-16).

8. According to the World Bank, deals were completed covering 60 million hectares of land in 2011, with two-thirds of that located in Africa (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-17099348).

9. Geopolitics and Migration // The African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Group and the European Union (EU). Policy Research Seminar Report. Cape Town, January 2014. P. 31.

10. Deitch T.L. Assistance to Development of African Infrastructure: a BRICS Priority // BRICS-Africa: Partnership and Interaction / Editors-in-Chief T.L. Deitch, E.N. Korendyasov. Moscow: Institute for African Sudies, 2013. P. 232.

11. Chinese construction projects in Africa employ predominantly Chinese rather than African engineers and workers, which hampers job creation and technology transfer. Even if the Chinese hire Africans, they often disregard international labor standards, causing enmity among the locals, and also neglect ecological norms in mining causing damage to the environment. Africans are also frequently unhappy about the quality of Chinese goods.

12. Korendyasov E.N. Russian Economic Interests in Africa // BRICS-Africa: Partnership and Interaction / Editors-in-Chief T.L. Deitch, E.N. Korendyasov. Moscow: Institute for African Studies, 2013. P. 94.

13. Ibid. P. 99.

14. Ibid. P. 101.

15. Ibid. P. 107.

16. See collection of articles on modern U.S. policies in Africa: African Studies Review. 2013 (September). Volume 56. № 2.

17. African peacemakers usually dominate the contingents of troops participating in African conflict resolution; for example the contingent in the Central African Republic is made of 6,000 African and only 2,000 French servicemen.

18. Moyo D. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. N.Y.: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010.

19. Kulkova O.S. BRICS in Africa in the Context of EU Interests BRICS-Africa: Partnership and Interaction / Editors-in-Chief T.L. Deitch, E.N. Korendyasov. Moscow: Institute for African Studies, 2013. P. 286.

20. Report "The Effects of EU Aid on Receiving and Sending Countries; a Modeling Approach (2012) (http://one.org.s3.amazonaws.com/pdfs/The_effects_of_EU_aid_on_receiving_and_

sending_countries_Report.pdf) prepared by ONE, the Overseas Development Institute and National Institute of Economic and Social Research, which indicates that by 2020, the 51 billion euro in the EU aid to the poorest countries will deliver to Brussels a profit rate of 20 percent, i.e. 11.5 billion euro.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |