By concluding a trade deal that gives China priority in purchasing Russian goods and services (the U.S.-China deal being a good template), Russia would revive bilateral economic relations. Compared to the diplomatic rapprochement of the two countries, their bilateral trade is still underperforming.

A long-term strategy requires long-term investment, while the latter requires secure return. To ensure there is a horizon for planning your business, you do not have to necessarily rely on budget support: this is where exclusive trade agreements can step in. This is exactly what the Trump administration did in January 2020, concluding an agreement that obliged China to boost U.S. imports by $200 billion above the 2017 level within two years, including energy ($52.4 billion), industrial production ($77.7 billion) and agriculture ($32 billion). The deal, among other effects, has revived the U.S. oil exports to China: supplies grew to 482,000 barrels per day (bpd) after a drop to 137,000 bpd in 2019 amid trade wars.

An exclusive trade deal between Russia and China could be smaller in volume and longer in tenor (aiming to increase the trade turnover by $100 billion in at least five years) to help resume, for example, the Eastern Petrochemical Company project, in which ChemChina planned to participate previously but which remained on paper. In return, Russia could extend the tax benefits, which are now granted to residents of the territories of priority social and economic development (TOSER), to all projects with Chinese shareholding. Thus, the success story of cooperation between Sibur and Sinopec in the Amur GCC would be replicated and should provide a new impetus to bilateral relations.

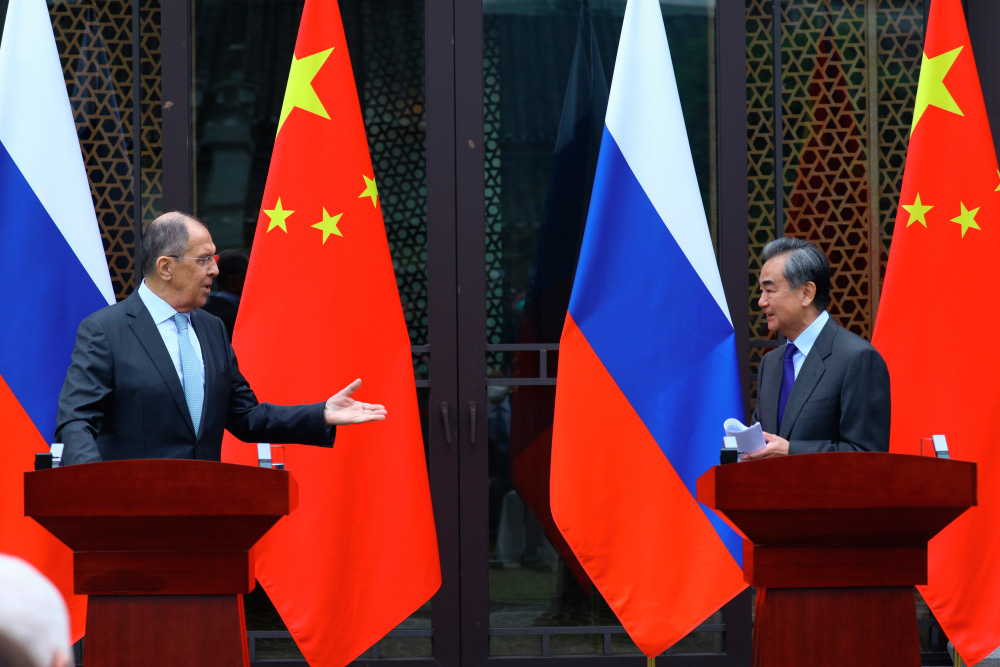

RIAC’s 6th “Russia and China: Cooperation in a New Era” conference in early June showcased once again the will of the two countries to develop exclusive relations. Over the past 1,5 years, during the global COVID crisis, both sides have even strengthened mutual trust. In December 2020, Russia and China extended their agreement on notifying of missile launches for ten years. The document was first signed back in 2009. In March, the Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation was prolonged, an agreement that has been cementing relations between the two countries for the past 20 years.

Economy contrasted with diplomacy

However, despite the long-sustained foreign policy rapprochement, Russia and China are far from fully utilizing their bilateral economic potential. In 2020, according to the Russian Federal Customs Service, China accounted for 15% of Russian exports, slightly more than the CIS (14%), but significantly less than the European Union (41%). In the structure of Russian imports, China is also behind the EU (24% versus 35%), although European food producers have been excluded from the Russian market since 2014.

In turn, Russia’s share was only 2% in Chinese exports in 2020 (with the U.S. share at 17%), and only 3% in imports (compared to 7% for the U.S., according to the ITC).

The same proportions are typical of mutual investments. By the beginning of 2020, according to the Bank of Russia, China accounted for less than 0.1% of accumulated direct investment from Russia (with the share of UK and Germany at 4.7% and 2.2%, respectively). As for the accumulated direct investments in Russia (private equity and debt instruments), China’s share reached only 0.8% in early 2020, while the share of France stood at 4.5%.

State support and guarantees

So far, Chinese investments are mainly focused on energy projects, directly or indirectly supported by the state. Yamal LNG plant is a good example (20% owned by CNPC, 9.9% by Silk Road Fund): to launch construction, Novatek raised a loan from the NWF (the sovereign National Wealth Fund). Another example is the Amur Gas Chemical Complex (AGCC) of Sibur (40% owned by Sinopec)—the project will enjoy tax benefits as a resident of one of the Far Eastern territories of priority social and economic development.

Ensuring guaranteed demand is equally important, as is the case for AGCC, which is located in close proximity to the world’s largest consumer of polyethylene and polypropylene, the basic petrochemical products. It is no coincidence that Sinopec acquired the share in the Amur GCC in December 2020. By that time, it became obvious that the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic would not undermine China’s growing demand for petrochemicals and gas chemicals: according to the ICIS forecast, China’s share in global polyethylene imports will grow from last year’s 35% to an even more impressive 43% by 2030.

Looking for viable opportunities

The lack of proper state support and guarantees restrains export in a number of other industries that could have enjoyed demand in the Chinese market. This is apparent in trade frictions between China and the U.S. (in 2019, China imposed a 25% duty on methanol imports from the United States) and Australia (in late 2020, China stopped buying Australian coal). And vice versa, it is possible to increase exports by searching for opportunities in the market niches where Russia’s sales potential is coupled with absolute competitive advantages, such as in helium market, where Russia may become one of the leading suppliers in the coming years.

Another option is the supply of Russian hydrogen, which may allow China to partially replace petroleum imports from other markets.

In 2018, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), some 1,790 hydrogen-fuel vehicles were operated in China out of 12,952 vehicles globally; the Chinese fleet grew to 6,180 out of 23,354 units by the end of 2019. And by 2025, China plans to increase the number of buses and trucks utilizing fuel cells to 50,000, jumping to 1 million by 2030.

Moreover, in 2035, according to the official plans of the Chinese authorities, half of vehicles sold should be climate-neutral, while the other half should be powered by hybrid engines or fuel cells. A similar shift will have to occur in Japan, where the IEA forecasts the number of fuel cell vehicles to increase from 3,633 in 2019 to 200,000 in 2025 and to 811,200 in 2030.

Russia has its competitive edge in hydrogen energy development, taking into account both global leadership in natural gas reserves (used for blue hydrogen stored in ammonia) and 50+ years of experience in nuclear and hydropower, needed for production of yellow and green hydrogen. Understanding these advantages is already reflected in regulatory plans: for example, according to the Energy Strategy adopted last year, Russia will increase its hydrogen exports from 200,000 tons in 2024 to 2 million tons in 2035.

Towards a New Trade Deal

We need to admit though that a long-term strategy requires long-term investment, while the latter requires secure return. To ensure there is a horizon for planning your business, you do not have to necessarily rely on budget support: this is where exclusive trade agreements can step in. This is exactly what the Trump administration did in January 2020, concluding an agreement that obliged China to boost U.S. imports by $200 billion above the 2017 level within two years, including energy ($52.4 billion), industrial production ($77.7 billion) and agriculture ($32 billion). The deal, among other effects, has revived the U.S. oil exports to China: supplies grew to 482,000 barrels per day (bpd) after a drop to 137,000 bpd in 2019 amid trade wars.

An exclusive trade deal between Russia and China could be smaller in volume and longer in tenor (aiming to increase the trade turnover by $100 billion in at least five years) to help resume, for example, the Eastern Petrochemical Company project, in which ChemChina planned to participate previously but which remained on paper. In return, Russia could extend the tax benefits, which are now granted to residents of the territories of priority social and economic development (TOSER), to all projects with Chinese shareholding. Thus, the success story of cooperation between Sibur and Sinopec in the Amur GCC would be replicated and should provide a new impetus to bilateral relations.