The current escalation in the Middle East has been described by many as a test of influence for China. For example, the media repeatedly suggested that the United States asked China to put pressure on Iran during the latest rounds of escalation, especially after the Israeli strike on the Iranian consulate in Damascus. Yet, if compared to Qatari, Egyptian or even U.S. influence, Chinese influence is rather weak in the current conflict. Beijing remains reluctant to get deeply involved in intra-regional politics of the Middle East, as this could damage its core interests, which remain centered on trade and economic cooperation, provoking new tensions with the United States.

The Arab monarchies of the Gulf are increasingly being held hostage to U.S.-China competition, with each country building the partnership in its own unique way. The Gulf states can conditionally be divided into three categories according to the level of their relations with China, with the level of strategic (i.e. military and infrastructural) ties with China as the main benchmark. There are the so-called “gamblers” (Saudi Arabia and the UAE); “fence-sitters” (Qatar and Oman); and “cautious conservatives” (Kuwait and Bahrain).

In any case, a rapid development of ties between China and the Gulf states is of considerable concern to the United States. Especially when it comes to the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The leaders of these nations have to keep the U.S. reaction in mind every time they intend to develop joint projects with China,

China’s growing economic influence in the Gulf faces a harsh U.S. response, especially in the strategically important areas. For a long time, China has not even sought to take part in intraregional politics, but the general logic of global confrontation with Washington is pushing it to become more actively involved in Middle Eastern affairs.

The current escalation in the Middle East has been described by many as a test of influence for China. For example, the media repeatedly suggested that the United States asked China to put pressure on Iran during the latest rounds of escalation, especially after the Israeli strike on the Iranian consulate in Damascus. Yet, if compared to Qatari, Egyptian or even U.S. influence, Chinese influence is rather weak in the current conflict. Beijing remains reluctant to get deeply involved in intra-regional politics of the Middle East, as this could damage its core interests, which remain centered on trade and economic cooperation, provoking new tensions with the United States.

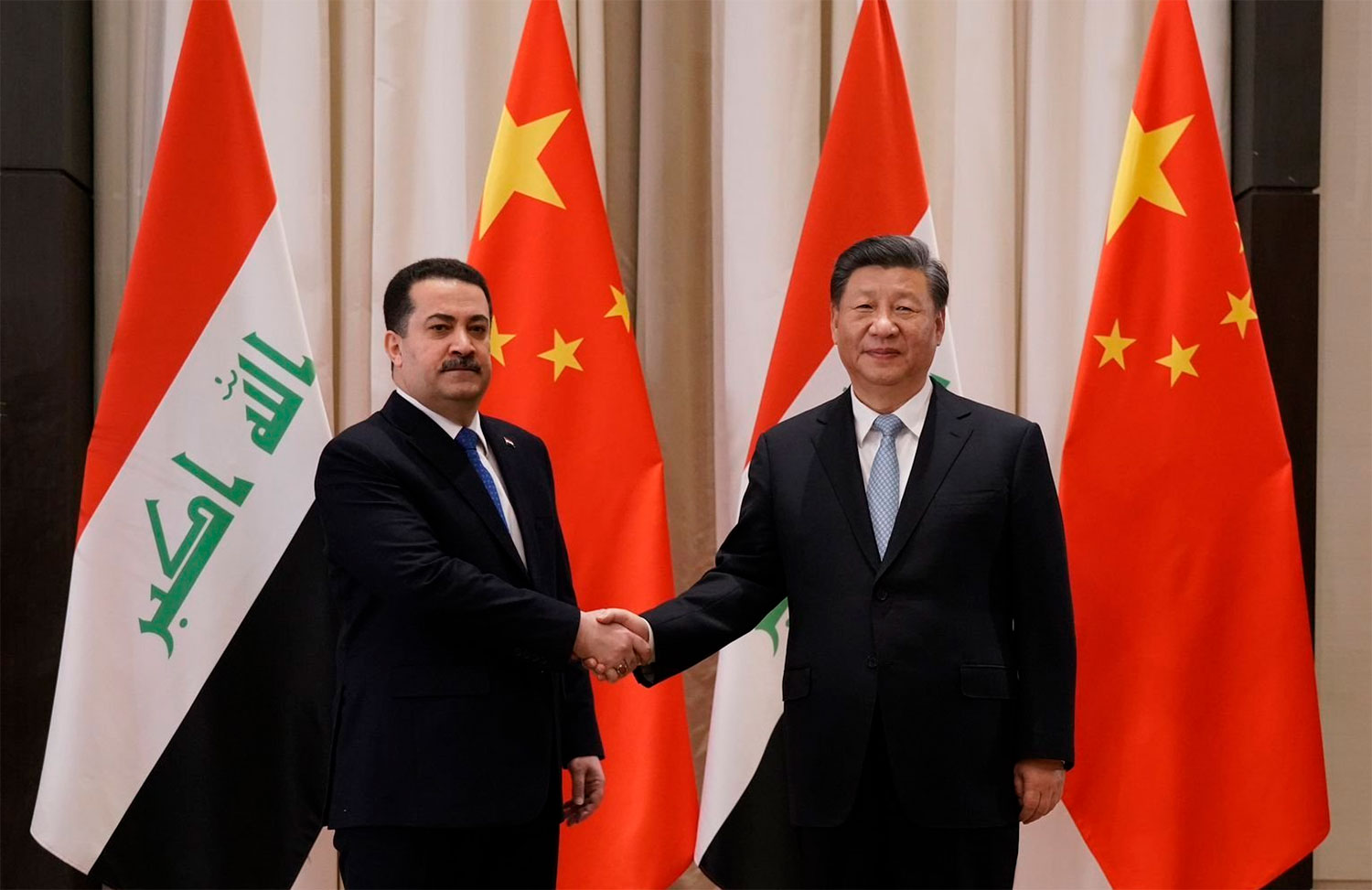

As a key trading partner of the Gulf states, China has more than doubled its oil imports between 2010 and 2020. Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Oman, Kuwait and the UAE act as key oil suppliers to the Middle Kingdom. Chinese companies are expanding their footprint in infrastructure and technology projects of the region. Chinese banks are providing funds for major projects, including in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, whereas Chinese construction companies were involved in building the UAE’s first railroad. In 2021, Chinese infrastructure investment within the Belt and Road Initiative increased by 360% while Beijing’s involvement in construction projects grew by 116%.

In 2016, the Chinese government released China’s Arab Policy Paper, which details Beijing’s interests in the region, including energy, trade and economic issues, as well as security. The latter aspect remains largely tied to the other two. The establishment of a naval base in Djibouti in 2016 was essentially driven by China’s economic and energy interests, with its purpose to protect trade routes from Asia to Europe through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. However, China has been slow to commit to overall intraregional stability. Learning from the experience of other great powers present in the Middle East, Beijing has noted that the region has become a significant challenge for them over time. Seeing how the U.S. has failed to deal with numerous regional challenges, Beijing has long sought to avoid getting involved in intraregional conflicts that could undermine its neutral stance and harm its economic interests.

Nevertheless, as 2023 has shown, the logic of China’s foreign policy inevitably draws it into the political situation in the Middle East, and its participation in the Saudi-Iranian normalization has only underscored this general trend. And there is a clearly visible link to long-term economic interests here. In the midst of stiffening competition with the U.S. and growing global instability, Beijing has decided to act proactively in order to reduce risks to its economy and energy sector. The joint Arab-Israeli air defense and missile defense system being created by the United States on the basis of the Abraham Accords is designed to contain the Iranian threat. Thus, the U.S. project was based on a confrontational idea directed against a key player in the region, which further increased the risks of escalation. This posed a threat to the stability of energy supplies to China and also threatened PRC logistics projects. It seems that the normalization of Saudi-Iranian relations allowed to arrest the progress in creating an Arab-Israeli alliance under the auspices of the United States and in a sense became a deterrent in transforming the current crisis in Gaza into a region-wide escalation.

However, the mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran has become another blow to U.S.-China relations. It is viewed by the United States in the context of global competition, whereas the PRC’s mediation between Iran and the KSA caused great concern in Washington. Some experts even described Riyadh’s cooperation with Beijing a “spit in the face of the United States.”

Such a reaction was most likely expected and considered natural in Beijing. In his report to the 20th CPC Congress in October 2022, Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasized the need for risk management in foreign policy. In his view, China’s new period of development involves “a combination of strategic opportunities, risks and challenges with the rise of uncertain and hard-to-predict factors.” The Chinese leader urged to prepare not for “bad weather” but for a “storm.” For this purpose, the risks for the Chinese economy, the source of which is in the Middle East, should have been minimized, because confrontation with the U.S. looks highly likely.

Gulf countries’ stance toward China

The Arab monarchies of the Gulf are increasingly being held hostage to U.S.-China competition, with each country building the partnership in its own unique way. According to French researcher Jean-Loup Samaan, the Gulf states can conditionally be divided into three categories according to the level of their relations with China, the main benchmark being the level of strategic (i.e. military and infrastructural) ties with China. Thus, he sets aside the so-called “gamblers” (Saudi Arabia and the UAE); “fence-sitters” (Qatar and Oman); and “cautious conservatives” (Kuwait and Bahrain).

The former are fostering relations with China in strategically important areas. Saudi Arabia and the UAE were particularly concerned about U.S. plans to reduce its presence in the region; this prompted them to “openly hedge against a U.S. withdrawal from the region.” Not only did they actively pursue trade with China, but they also began purchasing Chinese arms. Both nations have openly criticized the U.S. for certain aspects of its regional policies expressing disappointment with trends in building bilateral relations. For example, in June 2023, the UAE announced its withdrawal from the U.S.-led Combined Maritime Security Force in the Gulf.

The second category includes Qatar and Oman. They differ from the first group in that they have been much more cautious in developing relations with China. Both countries have attracted Chinese investment in port infrastructure and telecommunications, but have been careful not to draw much attention to these facts. On the security front, they have sought to strengthen their partnership with Washington. In 2022, Qatar was recognized as a major U.S. ally outside NATO, and it serves today as the main mediator between Hamas and Israel, largely promoting American interests. Oman signed a new strategic framework agreement with the U.S. in 2019, granting the U.S. military access to the facilities of Duqm Port, the site of the largest Chinese investment.

The third group of Gulf states, represented by Bahrain and Kuwait, has virtually no strategic ties with China. Although Kuwait has joined the One Belt, One Road initiative and counts on Chinese investment in the Silk City project, it is not keen on developing military cooperation with Beijing. The same is true for Bahrain.

China and U.S. in the Middle East

The rapid development of ties between China and the Gulf states is of considerable concern to the United States. Especially when it comes to the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The leaders of these nations have to keep the U.S. reaction in mind every time they intend to develop joint projects with China, as was evident, for example, in the issue of the KSA’s accession to BRICS. As Chinese experts point out, countries in the region are increasingly being drawn into the global U.S.-China zero-sum game. As U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently put it, “when it comes to new technologies, you can’t be both in the Chinese camp and in our camp.”

This trend is particularly apparent in areas such as 1) armaments; 2) advanced technology; and 3) nuclear energy.

The U.S.-Chinese competition for the allegiance of the Gulf states is most clearly manifested in the arms sector. Thus, in 2023, the U.S. canceled deliveries of F-35 fighter jets to the UAE in response to the Emirates’ purchase of telecommunications equipment from China’s Huawei. The UAE began to fear dependence on American suppliers and started building cooperation with Chinese manufacturers. In March 2023, the UAE Air Force signed a contract with the Aviation Industry Corporation of China for the purchase of 12 L-15AW combat trainer aircraft and held joint exercises with the Chinese Air Force in August. However, as a gesture of goodwill, the U.S. sent its rather old French-made Mirage fighters to the UAE exercises, rather than the more modern U.S.-made F-16s.

The advanced technology sector has also become a hotly contested area between U.S. and Chinese companies. In response to the close cooperation of a key Emirati technology company, G42, with the Chinese technology sector, the U.S. has restricted its access to U.S. Nvidia and AMD graphics cards, which are used to process the large data sets required for AI development. Given G42’s ambitions to develop AI technologies and build supercomputers, such restrictions proved critical. As a result, the U.S. government offered an alternative in the form of a partnership with U.S. companies. G42 had to agree, sell its Chinese assets and sign agreements with the American Microsoft. The latter announced investments worth USD 1.5 billion in G42’s AI technologies, while the director of its subsidiary OpenAI, Sam Altman, announced plans to turn the UAE into a “testing ground” for AI technologies. Thus, China has lost an important technological partner in the Middle East and is now likely to face U.S. attempts to limit Beijing’s technological cooperation with Riyadh.

Nuclear technology has also become an arena of U.S.-Chinese rivalry. In this area, the outcome of the standoff has not yet been decided, largely because of the Gaza crisis. The provision of American nuclear technology to the Saudis was supposed to be part of the so-called “grand bargain,” under which the KSA would establish diplomatic relations with Israel in exchange for the access to Washington’s latest military technologies, including F-35 fighter jets. Meanwhile, it is known that China’s CNNC is also bidding to build the first nuclear power plant in KSA, and, in response to slow progress in negotiations with the United States, Riyadh almost openly blackmailed Washington in the summer of 2023 with plans to give this project to China.

***

China’s growing economic influence in the Gulf faces a harsh U.S. response, especially in the strategically important areas. For a long time, China has not even sought to take part in intraregional politics, but the general logic of global confrontation with Washington is pushing it to become more actively involved in Middle Eastern affairs. This was demonstrated by the case of the Saudi-Iranian reconciliation, where Beijing played an important part.

Some Chinese experts believe that the level of China’s involvement in Middle Eastern issues will increase over time. At some point, to protect energy and trade interests, it may even be necessary to establish a military presence in the Middle East [1]. Considering how fierce the competition was in the course of the above-mentioned cases, the Gulf states may turn not into an AI “testing ground” but into an arena of U.S.-Chinese struggle. Even though China seeks to avoid this controversy, the logic of developing its U.S. relations inevitably leads to the unfolding of this scenario.

1. Lanyu Liu, “China’s Policy and Practice Regarding the Gulf Security,” in Stepping Away from the Abyss: A Gradual Approach Towards a New Security System in the Persian Gulf, eds. Luigi Narbone and Abdolrasool Divsallar (San Domenico di Fiesole: European University Institute, 2021), 81-94.