Collective Security in (Eur)Asia: Views from Moscow and from New Delhi

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Ph.D. in History, Academic Director of the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC Member

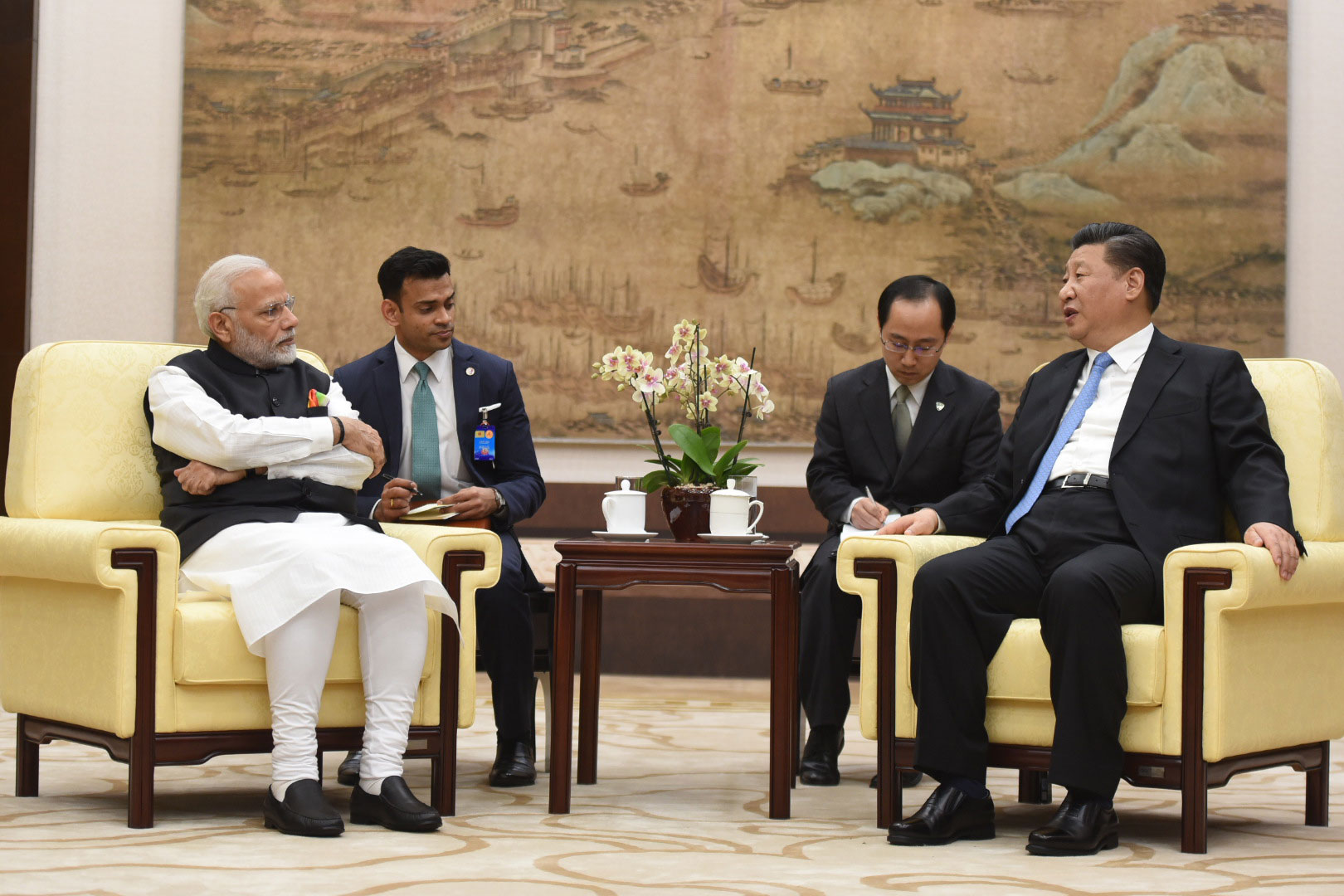

The idea of a collective security system in Asia has become a subject of discussions both in Russia and in India. Each of the two nations, given its size, power, history, military capabilities and political ambitions, has a lot of impact on the overall strategic situation in this part of the world, both are destined to play an active role in designing and erecting a new continental security architecture. Since bilateral Russian-Indian relations have always been marked by mutual affection, empathy and respect, one would suggest that leaders of the two states should look eye-to-eye on the desirable future of collective security in Asia. Indeed, the overall principles of collective security, as they are articulated by Russian and Indian leaders, look very similar to each other. There also seems to be a lot of personal chemistry between President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi that should help the two statesmen to harmonize their visions of the Asian security futures; this chemistry was manifested once again when Mr Modi has chosen to visit Moscow in July of 2024 on his first foreign trip after becoming the Prime Minister for the third time.

However, security concerns and challenges that Moscow and New Delhi face these days are often overlapping, but not completely identical. On top of that, the two states have somewhat different foreign policy experiences, decision-making mechanisms and diplomatic traditions. Differences in the two political systems also play a role in how they approach security matters in Russia and in India. Therefore, a closer look at the two Asia security perspectives may be helpful. In this paper, the author intends to focus not so much on common, but rather on divergent views that should be kept in mind while trying to forge new proposals on security in Asia and beyond.

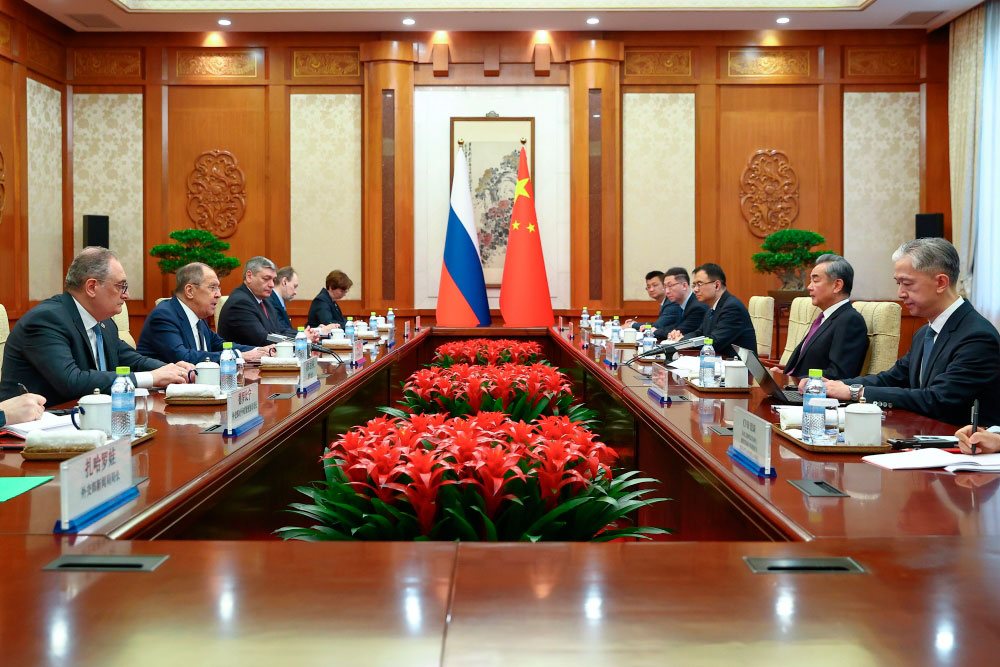

The attitudes to Washington and to Beijing constitute by far the most important and the most fundamental difference in Russia’s and India’s takes on the Asian security agenda. The challenge for the Russian leadership is how to balance its rapidly expanding foreign policy and defence ties to China and the stated commitment to an inclusive collective security system in Asia. The challenge for the Indian leadership is how to balance its growing engagement with the United States and its ambitions to play a more central role in Eurasian security matters. These challenges are likely to have a lasting impact on Russia’s and India’s foreign policy agendas and might also affect their bilateral relations.

If the main security challenge comes from overseas, it would be only logical and appropriate to limit the involvement of external players into the Asian security arrangements to as little as possible. In other words, Asian problems should have Asian solutions. From the Indian strategic perspective, Washington and Brussels (the latter stands for both NATO and the European Union) are not so much a part of the problem as a part of the solution for Asia’s security problems. Asia as an international subsystem open to external influences has clear advantages compared to Asia as a closed subsystem with potential security deficits. This divergence of views explains why Russia and India have such different attitudes to the concept of the Indo-Pacific.

In Vladimir Putin’s view, the new Eurasian (not even Asian) system should start with a dialogue between already existing organizations, such as the Russia-Belarus Union State, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). As it is viewed from Moscow, the system should ultimately embrace all nations of Asia and Europe including even members of the North Atlantic Alliance (with the notable exception of the United States) and members of the European Union. The underlying assumption that at some point the European partners of the United States along with Washington’s East Asia allies should demonstrate a new level of “strategic autonomy” from the US with their newly acquired Eurasian ties gradually overshadowing their old transatlantic bonds, which no longer serve fundamental Europe’s interests.

The Indian approach to the future collective security in Asia looks somewhat less ambitious, but arguably more practical. The positions articulated by Prime Minister Modi during his brief trip to Ukraine on August 23, 2024 suggest that the Indian leadership does not consider the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, as important as it is, to have an immediate formative impact on security in Asia and should therefore be considered in the European rather than in the Eurasian context though India as a leading power of the Global South is ready to do its best in trying to put the fratricidal conflict to an end. The sheer notion of “Eurasia” in New Delhi often stands primarily for the Central Asia and Afghanistan; it seems that the Indian leadership considers that the Asian—let alone the Eurasian—continent as simply too big and too diverse to be covered by a single comprehensive security arrangement.

It may be therefore more appropriate from the Indian viewpoint, to take a piecemeal approach trying to identify specific ‘region-tailored’ security arrangements for the Northeast Asia, the Southeast Asia, the South Asia, the Central Asia, the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and so on. Maybe, in some cases the approach should be even more incremental—e.g., in the Middle East one should single out the Gulf area as a separate sub-region with its own security dynamics.

The brief outline of Russia’s and India’s approaches to the idea of collective security in (Eur)Asia reveal a certain paradox and even a challenge to the contemporary IR theory. As a rising great power, India is supposed to demonstrate a more revisionist foreign policy pattern insisting on fundamental changes of the international system, which was to a large extent shaped before India even got its independence. On the other hand, Russia, as a mature great power, should stick to the existing status quo, since this status quo guarantees Moscow’s very special status within the system. However, in reality we observe a completely opposite picture—India tends to take a very cautious approach to the international system transformation, while Russia calls for a comprehensive revolution that would change the system once and forever.

Still, none of the above-mentioned differences in Russia’s and India’s approaches to continental security should prevent the two nations from working hand in hand with each other on many practical security matters. One an even argue that the Russian and the Indian approaches to security matters compliment each other and should generate the synergy needed to address the very complicated Asia security agenda. In many ways, the two nations can learn a lot from each other. Russia can share with India its diverse experience in global politics, including such critical areas as strategic stability, arms control and international crisis management in remote parts of the world, while India can offer Russia its experience in building its friendly neighbourhood, in well-calibrated “zone-balancing” and, above all in exercising appropriate “strategic patience” in dealing with critical security challenges.

The idea of a collective security system in Asia has become a subject of discussions both in Russia and in India. Each of the two nations, given its size, power, history, military capabilities and political ambitions, has a lot of impact on the overall strategic situation in this part of the world, both are destined to play an active role in designing and erecting a new continental security architecture. Since bilateral Russian-Indian relations have always been marked by mutual affection, empathy and respect, one would suggest that leaders of the two states should look eye-to-eye on the desirable future of collective security in Asia. Indeed, the overall principles of collective security, as they are articulated by Russian and Indian leaders, look very similar to each other. There also seems to be a lot of personal chemistry between President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi that should help the two statesmen to harmonize their visions of the Asian security futures; this chemistry was manifested once again when Mr Modi has chosen to visit Moscow in July of 2024 on his first foreign trip after becoming the Prime Minister for the third time.

However, security concerns and challenges that Moscow and New Delhi face these days are often overlapping, but not completely identical. On top of that, the two states have somewhat different foreign policy experiences, decision-making mechanisms and diplomatic traditions. Differences in the two political systems also play a role in how they approach security matters in Russia and in India. Therefore, a closer look at the two Asia security perspectives may be helpful. In this paper, the author intends to focus not so much on common, but rather on divergent views that should be kept in mind while trying to forge new proposals on security in Asia and beyond.

Threat perceptions

Eurasian Security Structure: From Idea to Practice

Needless to say, there is a lot of concurrence between Moscow and New Delhi on a broad range of security challenges across Asia. Both nations are concerned about potential regional crises that might break out in various places of the continent like Afghanistan or Myanmar, in Central Asia, in the Middle East or in the South Caucasus. Both have been historically vulnerable to international terrorism, both care a lot about continental food and energy security, about transcontinental migrations and about global climate change implications for Asia. Neither Russia, nor India is interested in nuclear proliferation in Asia or in an uncontrollable conventional arms race on the continent. However, there is still a visible divergence of positions on or, at least, of approaches to some of the main sources of security threats to Asia as they are currently seen from each of the two capitals.

For foreign policy decision-makers in Moscow, the core security challenge to Asian countries comes from overseas Western powers that have got involved in the continent over previous centuries and that have always been committed to keeping Asia disunited and fragmented to the extent possible in order to exercise an external control over the continent and to exploit Asia’s abundant natural and human resources. The political mainstream narrative in Moscow suggests that Great Britain was central in playing this disruptive role till the middle of the last century, and later on Washington replaced London on the Asian stage in its efforts to keep the continent divided and vulnerable to the Western malevolent influence. Needless to say that this vision to a large extent reflects the current intense geopolitical conflict between Russia and its Western opponents and is an organic part of a more general Russian leadership ‘s view of the world.

Therefore, it is considered indispensable for Russia and its partners in Asia to contain military blocks and political alliances created under US auspices (such as AUKUS and Quad) as well as US partnerships with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines that cannot be treated as contributors to ensuring continental security, but instead should be regarded as obstacles on the road to a collective security system in Asia. Another dangerous trend in Asia as seen from the Kremlin, is the continuous process of NATO’s globalization and, in particular, its ongoing activities in the Pacific and Indian Oceans that reached a new level after the 2022 Alliance Summit in Madrid.

The continental security landscape, as it is seen from New Delhi, is quite different than the vision projected from Moscow. Despite understandable negative sentiments associated with the colonial period of the national history, most of Indian politicians and scholars tend to take a more benign approach to the external political and even military presence on the Asian political and security stage, assuming that given the internal dynamics within Asia this presence can no longer be decisive. Asia is perceived to be big enough to accommodate everybody, including powerful external actors. For India, the real challenge to Asian security comes not from the remote United States or the North Atlantic Alliance, but rather from the neighboring China, which allegedly displays a clear intention to become the continental, if not the global hegemonic power, pursuing the goal of constructing “a uni-polar Asia in a multi-polar world”.

Though specific US attempts to put together various multilateral and bilateral security arrangements to contain China (AUKUS, trilateral Washington—Tokyo—Seoul cooperation in the Northeast Asia, US-Philippines security partnership and so on) are followed in New Delhi no less closer than they are followed in Moscow, the policy conclusions made in India might be very different from those made in Russia. Some Indian experts argue that if all US multilateral and bilateral arrangements succeed in blocking Beijing’s intended advances along the Pacific and Indian Oceans coast line, China might opt to focus its activities on the disputed Himalayan border with India, where New Delhi is not in a position to reset the power equilibrium that now favors Beijing. This means that in order to avoid being left out in the cold, India has no other choice, but to join the United States and the West at large in trying to deter Beijing through participating in various US-led multilateral bodies.

The attitudes to Washington and to Beijing constitute by far the most important and the most fundamental difference in Russia’s and India’s takes on the Asian security agenda. The challenge for the Russian leadership is how to balance its rapidly expanding foreign policy and defence ties to China and the stated commitment to an inclusive collective security system in Asia. The challenge for the Indian leadership is how to balance its growing engagement with the United States and its ambitions to play a more central role in Eurasian security matters. These challenges are likely to have a lasting impact on Russia’s and India’s foreign policy agendas and might also affect their bilateral relations.

Potential participants to the system

If the main security challenge comes from overseas, it would be only logical and appropriate to limit the involvement of external players into the Asian security arrangements to as little as possible. In other words, Asian problems should have Asian solutions. President Vladimir Putin argued that the existing military presence of Western powers in Asia (including US military bases and other Western military infrastructure) is nothing but a residual legacy of the Cold War; it should be brought to the minimum and ultimately—completely eliminated. Of course, the proposal is explicitly directed against the United States as well as against the North Atlantic Alliance that states its intention to continue increasing its political and military presence along the Indian and Pacific Ocean coastlines and deeper in the Asian mainland. The spectacular failure of the twenty year long NATO engagement in Afghanistan is often referred to in Moscow as an example of the destructive and self-defeating role that the United States and the West at large have historically played in Asia’s security matters.

This is not the view that would find many enthusiastic champions within the Indian political and defense establishment. Though the overall idea of gradually eliminating all external military presence in Asia is hard to oppose, the predominant opinion in New Delhi is that these days there is simply no combination of local actors that could even in theory reliably balance the overwhelming China’s military might. The strategic positions of India in Asia are further complicated by its long-term conflict with neighboring Pakistan that is likely to be on the side of Beijing in any potential China-India conflict. Given these realities, an engagement of overseas players should be regarded in New Delhi not as a negative, but rather as a positive factor contributing to credibly containing Beijing’s hegemonic ambitions.

From the Indian strategic perspective, Washington and Brussels (the latter stands for both NATO and the European Union) are not so much a part of the problem as a part of the solution for Asia’s security problems. Asia as an international subsystem open to external influences has clear advantages compared to Asia as a closed subsystem with potential security deficits. This situation can change only if in some future India together with its Asian partners will be in a position to balance China without involving external actors or if India and China can reach a strategic breakthrough in the overall bilateral relationship, which looks unlikely to happen anytime soon.

This divergence of views explains why Russia and India have such different attitudes to the concept of the Indo-Pacific. In Moscow, they often look at this concept as a US-designed strategic framework aimed at insulating China in the region and at turning nations of the Indian and Pacific Oceans coastline into obedient vassals of Washington. Moreover, Russian decision-makers often argue that one of the strategic goals of the concept is to marginalize Moscow in or even to exclude it from this vast geopolitical space and therefore the concept should be regarded not only anti-Chinese, but also anti-Russian. In New Delhi, they do not miss a chance to remind Russian counterparts that the concept of Indo-Pacifc has initially originated not in the United States, but rather in Japan and in India and that the concept is not about consolidating the US hegemony, but about maintaining ASEAN’s centrality in this huge economic and geopolitical space. The Indian perception is that in any case the concept is not directed against Russia and Moscow has no reasons to worry about it. Furthermore, India could even assist Russia in getting its entrance ticket to the club of Indo-Pacific nations, if Moscow decides to pursue this goal.

Prior to the launch of the Special Military Operation in February of 2022, there were active discussions within the Russian expert community about whether Moscow should indeed change or a least modify its explicitly negative approach to the concept of Indo-Pacific; some analysts even argued that this concept should regraded not as only a challenge, but also as a historic opportunity for Russia. However, it seems that the evolving geopolitical context has marginalized such contrarian views within the Russian expert community.

Geographical scope of the system

The Limits of Strategic Autonomy: Modi’s Visit to Ukraine

Here, unlike in the question of core participants, Russia seems to take a more inclusive approach compared to India. In Vladimir Putin’s view, the new Eurasian (not even Asian) system should start with a dialogue between already existing organizations, such as the Russia-Belarus Union State, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Furthermore, other influential Eurasian associations from Southeast Asia to the Middle East should join this multilateral arrangement. One can mention both regional platforms—Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sector Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and inter-regional ones—ASEAN+ and Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) as potential participants to the initiative. It goes without saying that any meaningful multilateral interaction within such a diverse group of institutions would be extremely complicated and—at least, at the initial stages of the dialogue—not very productive, but it is still worth trying.

As it is viewed from Moscow, the system should ultimately embrace all nations of Asia and Europe including even members of the North Atlantic Alliance (with the notable exception of the United States) and members of the European Union. The underlying assumption that at some point the European partners of the United States along with Washington’s East Asia allies should demonstrate a new level of “strategic autonomy” from the US with their newly acquired Eurasian ties gradually overshadowing their old transatlantic bonds, which no longer serve fundamental Europe’s interests. The United States has no right to dominate Europe forever, like it has no right to dominate Asia. In a way, this concept of “Greater Eurasia” can be tracked back to the ideas of ‘Greater Europe’ starching from Lisbon to Vladivostok that was popular in Moscow some twenty-five – twenty years ago. The difference, however, is that in the past the “Greater Europe” implied that pan-European institutions would gradually expand to Asia through Russia, the Central Asia and the South Caucasus, while the “Greater Eurasia” concept assumes that the European peninsula has to be gradually absorbed by a much larger and much more dynamic Asian continent.

The Indian approach to the future collective security in Asia looks somewhat less ambitious, but arguably more practical. The positions articulated by Prime Minister Modi during his brief trip to Ukraine on August 23, 2024 suggest that the Indian leadership does not consider the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, as important as it is, to have an immediate formative impact on security in Asia and should therefore be considered in the European rather than in the Eurasian context though India as a leading power of the Global South is ready to do its best in trying to put the fratricidal conflict to an end. The sheer notion of “Eurasia” in New Delhi often stands primarily for the Central Asia and Afghanistan; it seems that the Indian leadership considers that the Asian—let alone the Eurasian—continent as simply too big and too diverse to be covered by a single comprehensive security arrangement.

It may be therefore more appropriate from the Indian viewpoint, to take a piecemeal approach trying to identify specific ‘region-tailored’ security arrangements for the Northeast Asia, the Southeast Asia, the South Asia, the Central Asia, the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and so on. Maybe, in some cases the approach should be even more incremental—e.g., in the Middle East one should single out the Gulf area as a separate sub-region with its own security dynamics. Each of such arrangements should have its own list of participants, rules of engagement, security priorities and expected institutional arrangements. For instance, the continuous Indian interest in SCO largely depends on the ability of inability of this organization to make a viable contribution to political stability and economic progress in Afghanistan, which was reflected in the India’s 2023 SCO Chairmanship agenda. Maybe, at some point in time, all of these smaller security arrangements will merge into a more universal Asian or even Eurasian collective (or more limited cooperative) security system, but one cannot possibly hope that this will happen in the foreseeable future.

In many ways, India's security strategy is still focused on its immediate neighborhood and the Indian Ocean region. In New Delhi they emphasize the need for “zone balancing,” which would allow to deter coercion from external powers (mostly China) while fostering security cooperation with littoral states. Initiatives like the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) showcase India's intent to establish itself as a responsible regional leader and a key security provider in South Asia. It would be fair to conclude that the remaining focus on the immediate South Asia neighbourhood allows New Delhi to test specific procedures, mechanisms and security regimes that could be later applied at a higher than sub-regional level.

In a way, this distinction between a more universal and more incremental vision of the Asian security reflects different schools of foreign policy thinking that dominate the expert and political discussions in Moscow and in New Delhi respectively. In Russia they usually tilt to a deductive paradigm to international relations assuming that one should start with addressing bigger strategic problems and then going down to smaller tactical ones. The Russian and formerly the Soviet tradition has always put special emphasis on general frameworks and fundamental principles (like the Helsinki Decalogue—the ten provisions of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe signed on August 1, 1975 by the leaders of 33 European countries, the United States and Canada). Some foreign experts conclude that the recent Russian proposals on Eurasia security system are aimed at gradually building something like a Eurasian model of OSCE.

However, even Russians themselves are doubtful that anything like a new Helsinki Final Act will find a lot of support in South Asia, especially in view of the ongoing complete desegregation of European security institutions. In fact, the ongoing West-Russia crisis has been a heavy blow to the top-down approach to international security arrangements not only in Europe, but everywhere. In India the inductive paradigm seems to be more popular; one should start dealing with smaller incremental matters first and than, when the participating sides accumulate enough mutual trust and experience in working together, they can try climbing up to more sensitive, controversial or more strategic matters. Only future can tell us whether this bottom-up approach can lead to a multidimensional and sustainable security system in Asia.

The legal arrangements

RIC Trilateral Cooperation Needs Enhancement

Historically, Russia has always taken a more legalistic attitude to international relations than India has done; the former inherited mostly the continental European international public law culture and constitutional traditions, while the latter emerged under a strong influence of the Anglo-Saxon precedent law tradition. The importance of strict adherence to formal norms of international public law is emphasized in the new version of the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation adopted in March of 2023, in the document the is also a clear distinction between “international law” and “rules-based order”; it is noted that any “further promotion of the concept of a rules-based world order is fraught with the destruction of the international legal system and other dangerous consequences for humanity”.

The legal purity of potential international arrangements has always been a matter of concern to Russian diplomats involved in drafting bilateral and multilateral treaties, agreements, etc. The Russian leaders are apparently convinced that informal commitments that are not legally binding and are not accompanied by proper verification mechanisms are not likely to work out or to be sustained over time. The predominant perception in the Kremlin is that Moscow’s Western partners let Russia down many times after the end of the Cold War by making various informal commitments to the Russian side (like the alleged commitment of 1990 not to advance NATO in the Eastern direction) that did not last for too long.

India appears to be much more relaxed on the legal dimension of the future collective security arrangements in Asia. One can even argue that the Indian leadership may be purposely unwilling to enter into various legally binding agreements because these agreements could limit the Indian foreign policy freedom of action that they value so much in New Delhi. Even the term “alliance” is still viewed with suspicion by many in the Indian strategic community. After all, a nation can always find a way to walk out of any legally binding international treaty, if it comes to the conclusion that this treaty no longer serves its interests. A continuous commitment to an international agreement should be based not so much on any specific legal formulas and intrusive verification procedures, but rather on the understanding that the agreement serves specific national interests.

It should be noted that over last decade, since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office for the first time in 2014, his approach to collective security has evolved significantly due to the changing geopolitical environment. The traditional emphasis on maintaining India’s strategic autonomy, the principles of non-alignment, and on building bilateral relations with major powers, India has gradually developed more appetite for more than purely sub-regional collective action and multilateralism. However, this transition has not yet resulted and might not result into India’s acceptance of the Russian legalistic position on international security in Asia. It would be fair to say that New Delhi has accumulated more experience in development focused rather than in security focused multilateralism. Moreover, the ongoing shifts in the Indian approach to multilateralism might signal a gradual transition in the direction of multilateral containment and deterrence rather than collective security how the latter is understood in Moscow.

This difference of approaches partially explains why Russia has always insisted on legally binding commitments from its arms control negotiations partners, and India has often been reluctant to advance a fast institutionalization track for such important entities as SCO, BRIC or even for Quad [1]. In all these settings New Delhi would prefer to have commitments a la carte that is to give participating sides the right to decide on the preferred levels of their specific involvement in particular projects or formats of cooperation. The legalistic approach is undoubtedly more ambitious, but is more rigid at the same time, while the situational one might be more ambiguous, but also more flexible, which is very important under the current challenging political circumstances [2].

Security and development

New Agenda of Russia-India Relations

The Russian approach to the Asian collective security system implies close links between security and development as the two most important dimensions of the desirable future Asian order. Future security mechanisms should be complimented by trade facilitation, financial integration, continental transportation corridors, multilateral development projects, human contacts and so on. Though in Russia, like in India, there are those who remain concerned about the rapidly growing China’s economic might (and this might be one of the reasons why Russia, as well as India, never directly joined the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative), in Moscow they nevertheless tend to believe that there can be no sustainable development without security and no stable security without development. This is why Moscow has always tried had to get a balanced mix of security and development cooperation components with both China and India—being more successful with Beijing rather than with New Delhi. The inseparable connection between security and development is particularly explicit is such areas as terrorism, environmental threats, climate change, the spread of organized crime, human trafficking, etc. In this equation, for Russia security has always played the leading role; in Moscow, immediate economic interests have always been subordinated to more important security priorities.

In principle, such approach should not meet any resistance in India—the national leadership under Prime Minister Narendra Modi also puts an emphasis on common development as a top priority, which definitely has a profound impact on the nation’s foreign policy and security priorities. Still, it looks as if in New Delhi they tend to take a more compartmentalized approach to security and development than they do in Moscow. For instance, for a long time India had great political relations with Russia, while the economic dimension of this relationship was clearly underdeveloped. This very evident gap between the political and the economic dimensions of the bilateral relationship was a matter of concern for both New Delhi and Moscow, but it did not seem to negatively affect the ability of the two sides to work together on important security related matters.

On the other hand, it is clear that in New Delhi they consider Beijing to be not only a formidable geopolitical adversary, but also a powerful economic adversary. This is one of the reasons why India, for instance, decided to stayed out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), but joined the US-initiated Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). At the same time, despite all the political disagreements and even direct military clashes between the two nations, in the fiscal year 2023–2024, China emerged as India's top trading partner, with two-way trade amounting to approximately USD 118.4 billion, slightly surpassing the United States, which had USD 118.3 billion in trade with India during the same period. It would be impossible to imagine the Russian-US trade booming in a similar way parallel to growing political tensions between the Kremlin and the White House. This difference between Moscow and New Delhi is not accidental—it is rooted in deep distinctions between the Russian and the Indian economic and political systems: in Russia even the most important economic interest groups have always been less powerful than similar groups in India.

Both approaches have their respective advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, in the XXI century is becomes increasingly hard to separate security and development. On the other hand, overloading the security agenda with development items might make an agreement too complicated and almost impossible to achieve. Besides, if long-term development prospects are completely subordinated to immediate national security interests, serious distortions of the foreign policy agenda become very likely, if not unavoidable.

Moving forward

Why Bharat Matters

The brief outline of Russia’s and India’s approaches to the idea of collective security in (Eur)Asia reveal a certain paradox and even a challenge to the contemporary IR theory. As a rising great power, India is supposed to demonstrate a more revisionist foreign policy pattern insisting on fundamental changes of the international system, which was to a large extent shaped before India even got its independence. On the other hand, Russia, as a mature great power, should stick to the existing status quo, since this status quo guarantees Moscow’s very special status within the system. However, in reality we observe a completely opposite picture—India tends to take a very cautious approach to the international system transformation, while Russia calls for a comprehensive revolution that would change the system once and forever.

Still, none of the above-mentioned differences in Russia’s and India’s approaches to continental security should prevent the two nations from working hand in hand with each other on many practical security matters. One an even argue that the Russian and the Indian approaches to security matters compliment each other and should generate the synergy needed to address the very complicated Asia security agenda. In many ways, the two nations can learn a lot from each other. Russia can share with India its diverse experience in global politics, including such critical areas as strategic stability, arms control and international crisis management in remote parts of the world, while India can offer Russia its experience in building its friendly neighbourhood, in well-calibrated “zone-balancing” and, above all in exercising appropriate “strategic patience” in dealing with critical security challenges.

1. Though many in Russia are concerned that Quad might eventually turn into a full-fledged US-led defense alliance, an unbiased analysis of India’s approach to Quad demonstrate that New Delhi is unlikely to move in this direction. See: Sullivan de Estrada, K. India and order transition in the Indo-Pacific: resisting the Quad as a ‘security community.’ The Pacific Review, 36(2), 2023, pp.378–405. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2022.2160792

2. The optimal balance between legally-binding and non-legally-binding international agreements is a complex question and a subject of intense expert discussions all over the world. See: Non-Binding Agreements // Berkeley Law. 10.11.2021. URL: https://www.law.berkeley.edu/podcast-episode/non-binding-agreements/

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

The principle of indivisibility of security, not implemented in the Euro-Atlantic project, can and should become key for the Eurasian structure

Why Bharat MattersReview of the Dr. S. Jaishankar’s book “Why Bharat Matters”

RIC Trilateral Cooperation Needs EnhancementCan Moscow make a meaningful contribution to an improvement in China-India relations?

New Agenda of Russia-India RelationsOn the transformation which was hard to imagine even five years ago

Inventing Eurasia: How Russian Proposals for a Collective Security System Harmonize with South Asian RealitiesRussia’s emphasis on ensuring security to accelerate economic development will allow the main stakeholders to step back from differences, focus on a positive agenda and at least start a dialogue on building a Eurasian security system

The Limits of Strategic Autonomy: Modi’s Visit to UkraineThe motives of the visit are more symbolic than substantial, as New Delhi desires to ascertain whatever role it could play in the Ukrainian peace process

Eurasian Security as a Communicative Practice: Tasks for Russia and ChinaDeveloping a new, understandable language of “sustainable security” in Eurasia, thanks to which everyone will be able to contribute to solving and anticipating common problems in their own way, is necessary