Does the World Need More Oil?

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 3) |

(1 vote) |

International College of Economics and Finance, Higher School of Economics

The situation on the oil market is a cause for concern – members are worried, and increasingly asking questions: prices continue to fall and there seem to be no signs of trend reversal in the offing. Nor is there any consensus among experts on this issue – forecasts vary from the cautious optimism prompted by another decline in the number of oil-producing rigs in the U.S. to broad statements about the end of the era of high oil prices and the transition to fundamentally new types of energy.

The situation on the oil market is a cause for concern – members are worried, and increasingly asking questions: prices continue to fall and there seem to be no signs of trend reversal in the offing. Nor is there any consensus among experts on this issue – forecasts vary from the cautious optimism prompted by another decline in the number of oil-producing rigs in the U.S. to broad statements about the end of the era of high oil prices and the transition to fundamentally new types of energy.

This anxiety has chiefly been caused by the numerous unexpected events in July and August, which saw the lifting of sanctions against Iran, disappointment in the pace of growth in the Chinese economy, the situation in the Middle East, and OPEC member countries’ policy. Meanwhile, the oil price is a key factor determining the economic development of many countries, including Russia, where oil production and sale accounts for over 40 percent of revenues to the federal budget, among other major exporters that are heavily reliant on oil.

The most likely scenario is this: over the short-term oil prices will continue to fall, albeit with possible short-lived, insignificant increases. As winter approaches, most likely in October-November, the situation will improve somewhat and the market will briefly become bullish again before the bear trend reasserts itself. The estimated price corridor will range from 35 dollars to 70 dollars per barrel. Long-range forecasts are difficult to make due to the large number of variables.

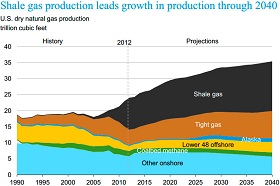

Factor 1: The U.S. shale revolution

The United States, with its notorious shale revolution, is one of the main driving forces shaping oil prices. This generates market uncertainty, making forecasts vary from pessimism to optimism and back again. As of today, given the sustained decline in oil prices, some experts tend to favor a scenario that is, from the United States’ perspective, pessimistic, predicting an imminent end of shale and massive bankruptcy among U.S. firms. However, these bold statements seem somewhat premature: during its two-year history, the shale revolution has already proved its flexibility and stability.

The latest technology and a steady decline in oil production cost are among the shale companies’ key strengths. For example, in 2012 this cost ranged from 64 dollars to 97 dollars depending on the deposit. By 2015, it fell by more than 30 dollars. The productivity rate is also rising and increased this year by 34 percent. According to some estimates, even if the number of oil-producing rigs falls by 20 percent, crude oil production will still grow. Therefore, this indicator, which has prompted speculations on this issue, does not clearly testify to a reduction in U.S. oil production . Thus, despite the difficult position resulting from high production costs, shale companies have successfully kept their heads above water and do not intend to leave the market.

However, these seemingly encouraging statistics raise a number of questions and doubts. Given the above figures, as things stand, shale companies have already been operating at a deficit for some time. This discrepancy becomes particularly striking if we remember winter 2014, when oil prices fell below 55 dollars a barrel. Nevertheless, talk of the shale boom ending was not backed up by reality: only five of the hundreds U.S. oil companies have declared bankruptcy.

Despite the difficult position resulting from high production costs, shale companies have successfully kept their heads above water and do not intend to leave the market.

The shale revolution’s viability is based on so-called junk stocks: the zero interest rate policy drove investors to high-yielding markets with kamikaze bonds. Thus, with no real profits, U.S. oil companies simply built up their debt. Given the current steady decline in prices, investors in the oil shale industry are likely to panic, and will try to get rid of the shares, causing their rapid depreciation.

Amidst these developments, the inexorable approach of October 2015 raises the greatest fears, as it could become a kind of Judgment Day for the majority of slate companies. During this month, bank management reviews the terms and the size of loans for companies in this high-yielding sector. In this context, the biggest danger comes less from the fall in oil prices, than from its protracted nature. Most small shale companies cannot expect continued funding for their projects.

The prediction of a temporary improvement in the market in autumn is largely based on this “fateful” October. However, there is little sense in laying hopes on it lasting much longer: as soon as prices rise and stabilize, shale companies will return to business. It won’t take them long: the operation of the oil wells can be resumed within a week, and oil rigs are mobile. Moreover, during the resumed talks, U.S. companies will have an opportunity to review such articles of expenditure as the manning level, rental and equipment, transportation cost and, having lowered production costs, return triumphantly to the market. All things considered, the fall in prices is unlikely to affect the long-term development prospects of oil production in the U.S.: the decline of the shale revolution era is not yet in the offing.

Of course, we should keep in mind that the U.S. has conventional deposits, which account for over half its entire oil production but cannot satisfy domestic consumption needs. It was the shale revolution that delivered the country from the need for oil imports, which in 2007 amounted to almost 14 million barrels per day [1], and since then has declined steadily. In other words, U.S. oil production is largely shaped by shale.

Factor 2: Iran

The prediction of a temporary improvement in the market in autumn is largely based on this “fateful” October. However, there is little sense in laying hopes on it lasting much longer: as soon as prices rise and stabilize, shale companies will return to business.

Iran is another country that has huge oil reserves, and therefore plays a key role in shaping prices. The recent lifting of sanctions, coupled with OPEC’s announced increase in oil production, finally gave the country a free hand in returning its market share. The main question is this: how much time will it take Iran to recover its pre-sanctions production level?

The estimates vary from a couple of months to several years. It is quite hard to deliver a reliable analysis due to the protracted nature of the sanctions imposed on the country almost three years ago and, consequently, to a possible depletion of reserves or serious damage to the existing oil fields in Iran. The Iranian Constitution, which prohibits involving private and foreign companies in extracting natural resources, is another factor that can slow the pace of oil production.

In the next two or three months, Iranian oil is unlikely to arrive on the market: the agreement covers a complete lifting of sanctions only after foreign experts have inspected the country’s nuclear facilities.

There is little doubt that, in the next two or three months, Iranian oil is unlikely to arrive on the market: the agreement covers a complete lifting of sanctions only after foreign experts have inspected the country’s nuclear facilities. However, the participants’ market expectations play a key role, that deserves to be recognized: if negotiations on the lifting of sanctions could reduce the cost of a Brent barrel by as much as 5 percent, it could be argued that good news from Iran, which will not be slow to arrive, will continue to lower oil prices. A lot of countries and large companies have already expressed their willingness to invest in the country’s economy and participate in joint projects to develop oil fields. Fundamentally new types of contracts are being concluded that make it possible both to attract new investors and to keep them. Accordingly, a powerful lobby is being mounted in the United States and the EU in the event of revising the current agreement and resuming sanctions. This suggests that the “ghost” of Iran is most likely to haunt the market for long enough to generate occasional but noticeable shifts in prices.

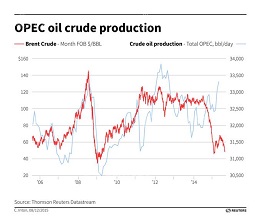

Factor 3: OPEC policy

How much time will it take Iran to recover its pre-sanctions production level?

OPEC is the largest actor on the oil market and until recently had the opportunity to directly dictate the price. The U.S. shale revolution changed the situation dramatically. The emergence of such a strong opponent deprived the Arab sheiks of the reins of power. Given the ever-decreasing price of oil, the logical solution would have been to cut production and restore the balance of supply and demand.

However, as became known from OPEC’s June report [2], member countries increased exports again, exceeding their own quotas by 30 million barrels a day. At first glance, such a policy seems ill-conceived: it would have been much more profitable to reduce the oil supply, thereby increasing its cost and the profits generated, than it would be selling it cheaply in large quantities. According to J.P. Morgan equity research analysts [3], Saudi Arabia’s decision to maintain the current production rate will cost the country about 110 billion dollars a year, provided the price of a barrel of Brent does not fall below 60 dollars.

However, an analysis of the long-term perspectives reveals another danger: if a country reduces oil production, it risks losing its share in an already oversaturated oil market. In this case, its losses will significantly exceed the figure indicated by the analysts above. Obviously, this logic is shared by the rest of the market: lifting the sanctions against Iran and the U.S. shale revolution caused price panic and everyone wants to get a piece of the pie. It is also worth noting that it will be difficult for member countries to reach agreement: most are currently facing an acute need for funding for their own budgets, and in these conditions, are unlikely to welcome a significant decline in oil production.

The “ghost” of Iran is most likely to haunt the market for long enough to generate occasional but noticeable shifts in prices.

This is a typical “Prisoner's Dilemma:” it is impossible to reach an agreement that allows every participant to derive higher profits, as there is a prevailing fear that other actors would violate it, pushing competitors out of business and getting their share. In this case, the market can not return to equilibrium, and artificially low oil prices are likely to last for a considerable period.

It was recently reported that OPEC countries plan to convene an emergency meeting (the next meeting is scheduled for December 4, 2015) to address the problem of crude oil prices, and the lifting of sanctions against Iran. It is expected to review the oil export quotas. Despite this encouraging news, the basic question remains: how soon will OPEC countries be able to organize this meeting and agree on the volume of oil production?

Lifting the sanctions against Iran and the U.S. shale revolution caused price panic and everyone wants to get a piece of the pie.

There is a current theory that OPEC deliberately exceeded its own quotas to lower oil prices and squeeze out of the market weaker actors, chiefly U.S. slate companies. These arguments suggest that the best moment for the next intervention to establish control over prices will not come until late October 2015, when a number of American oil companies may go bankrupt. Accordingly, supply will fall and demand will increase as the U.S. is forced to return to the market as an oil importer.

However, it does not seem reasonable to pin great hopes on such an outcome. The situation is aggravated by the fact that the Arab sheiks seem to believe that in the near future oversupply will be absorbed by increased demand from developing countries’ rapidly growing economies, and therefore they see no reason to revise their policy. Hence, the next OPEC meeting and, accordingly, any major changes in the oil market, should not be expected before the end of October.

Factor 4: Russia’s policy

, Russia has stepped up oil exports even faster than OPEC: in the first six months of the year it increased exports by almost 10 percent and ranks top in in the production of this type of fuel.

It is obvious that Russia had to follow the general trend of increasing oil production. In this environment, any alternative strategy would have led to the loss of market share, and, accordingly, of one of the main sources of revenue for the state budget. Given today's tough economic times for the domestic economy, it would only exacerbate existing problems and push the country closer to the next crisis. According to recent data, despite the freezing of several major projects in the Arctic, Russia has stepped up oil exports even faster than OPEC: in the first six months of the year it increased exports by almost 10 percent and ranks top in in the production of this type of fuel. This is not surprising, given that the income from its sale were nearly half that of the previous year: the economy is beginning to feel the negative impact of this over-dependence on oil exports.

The exhausted budget needs replenishing. However, due to the landslide in prices, the same volume of oil exports can no longer deliver the required budget revenues. This forces the country to increase production at a record pace, leading to further price reduction and intensifying the need for a bigger “hit.” The country is caught in a vicious circle, which seems impossible to break. Evidently, Russia has failed to break its oil addiction, and is now paying dearly for it.

Russia has failed to break its oil addiction, and is now paying dearly for it.

The fact that the ruble is pegged to the oil price seems to be the only bright spot in this situation: cheaper oil will devalue the ruble substantially, playing into the oil companies’ hands, as sales will go up and boost revenues. The budget will benefit from it as well as it will be replenished by the devalued ruble. However, this factor will weaken the pendulum effect, than remove it completely. The fate of the country's budget is fairly obscure, but for now one thing is clear: Russia will not turn the tide on the oil market; rather it will exacerbate the current situation.

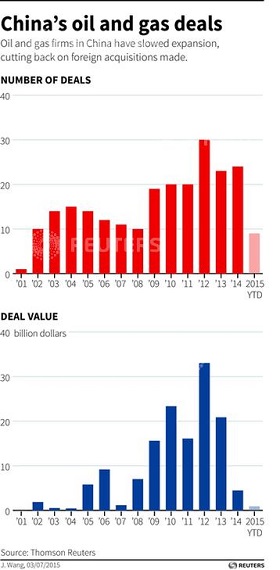

Factor 5: China’s growth rate

China’s rapidly developing economy and growing role as a major oil importer is one of the key factors impacting oil prices. In early May 2015, great hopes were laid on it, however, it did not live up to these expectations. In July, GDP growth began to slow down, reaching only 7 percent against the predicted 7.5 percent. It is not entirely clear what the figures indicate. Some experts predict a recession in China; others believe that we have witnessed a natural correction or slowdown, rightly arguing that no economy can grow at such a rapid rate forever. Nevertheless, there are other warning signs: the stock market collapse, a reduction in business activity, a decline in demand for real estate and cars, decreased exports and higher inflation.

Investors and the Chinese leadership should pay particular attention to these signals. They testify to a number of imbalances in the country's economy. Unless it addresses these problems, China is unlikely to continue its steady transition from a developing economy to a developed one.

It should also be noted that the stock market collapse is likely to have serious consequences for the country. A number of major investors and fund managers have expressed concerns about their investments in China and an associated significant increase in risk. Frightened by these and similar statements, investors, not affected by the stock market collapse, are likely to become panic-stricken too. This may provoke a sharp outflow of investment, which took so much effort to attract in the first place, and deliver an even greater economic slowdown. Against this background, expecting any significant increase in demand for oil from China seems rather unreasonable.

We can hardly expect a significant increase in imports by the second main oil consumer – Europe. The economies of most EU countries are facing a gradual slowdown: in the second quarter their GDP growth fell to 0.3 percent. There are many alarming “symptoms” similar to those seen in the Chinese economy: stock market decline, overall slackening of business activity, combined with decreased industrial production. It is worth noting that there are already some signs of improvement, namely the revival of Europe’s real estate market. Nevertheless, there are no reasons to expect a significant increase in demand for oil in the near future.

India, which continues to develop rapidly, has substantially increased oil imports in 2015. Nevertheless, even such a large economy cannot reverse this bearish trend.

Russia will not turn the tide on the oil market; rather it will exacerbate the current situation.

For now, two major actors account for the main market uncertainty: OPEC, whose policy has literally shaken the market in July 2015, and the United States with its shale revolution and unpredictable dynamics.

A number of political variables such as a possible lifting of the ban on American oil exports are a no less significant factor. The lifting of the ban seems unlikely for the time being, but the developments in OPEC are worth following very closely.

We should not rule out a possibility of a black swan scenario. There is a possibility that OPEC, scared by the results of its own actions, could convene an emergency meeting before October and quickly redistribute its internal quotas, taking into account the imbalance of market supply and demand, as well as the lifting of sanctions against Iran. This would deliver an interesting scenario: OPEC will control the important market player that is Iran, and the latter would no longer be able to increase oil exports at will.

Some experts predict a recession in China; others believe that we have witnessed a natural correction or slowdown, rightly arguing that no economy can grow at such a rapid rate forever.

Second, due to rising prices, many countries will have fewer reasons to further increase production, which they did as a last resort to fund their budgets, because the low cost of previous oil exports had not accounted for the necessary budget revenues. Even a return to business of such a strong actor as the U.S. would not significantly affect the bullish trend. Unfortunately, this optimistic scenario stands little chance of success.

Nevertheless, despite the pessimistic short-term forecasts for oil exporters, the long-term outlook leaves room for some optimism. A sufficiently prolonged decline in oil prices could become a catalyst to jump-start growth in developing countries’ economies and, accordingly, generate their new wave of demand for fuel. The development of such a favorable scenario for exporting countries requires oil prices stay low throughout the year, which is entirely probable in the current situation. Despite artificially high supply, the market will find a way to stabilize on its own.

1. Amy Harder. U.S. Congress Considers Lifting Crude Oil Export Ban // The Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2015.

2. OPEC oil monthly report. June 10, 2015.

3. CEEMEA Equity Research. July 23, 2015.

(votes: 1, rating: 3) |

(1 vote) |