Of all the types of hydrocarbons, coal has been in use the longest. China is known to have extracted coal as early as the 4th century B.C. Unlike oil, coal has historically been used in everyday life for heating purposes, and it played a key part in the development of human civilization as a universal fuel for a long time. The future prospects of coal today, however, are uncertain, with most western countries trying to lay the foundations for an emissions-free energy future and thus giving up the fuel. The developing world cannot afford to adopt such a principled position, but will get there sooner or later, gradually replacing coal will other energy sources.

Although coal has been used in Russia for centuries, industrial mining only truly took off in the 20th century. Until 1869, coal was imported into Russia duty-free, thus making it difficult for the domestic mining industry to compete against European – primarily British – producers. As a result, by the beginning of the 20th century, even Belgium was producing more coal than the Russian Empire. After the 1917 Revolution, the Soviets adopted a policy to electrify the country, develop metallurgy and establish new industrial clusters, which led to the gradual development of the Kuzbass Coal Basin and other coal mining regions across Russia. It was not until World War II, however, that the USSR began mining for coal in Siberia, as the country was in dire need of the fuel following the loss of the Donbass Black Coal Basin to the Nazis.

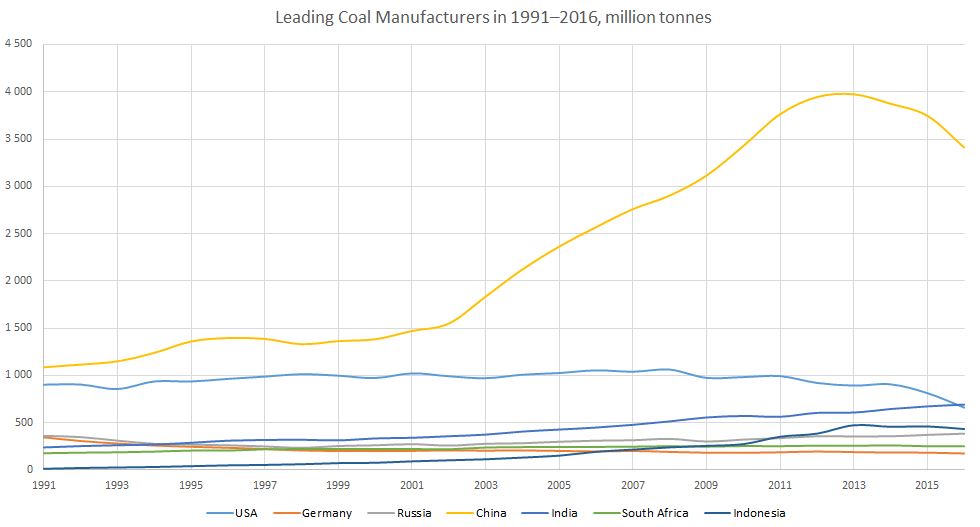

The first decades after World War II became known as the “coal era” – not only in the USSR, but also in the leading energy powers in the West. In the 1950s and 1960s, record amounts of coal were extracted in the United Kingdom, Germany and France, the countries which had pioneered the coal mining industry. In the following 10 to 15 years, the USSR hit its coal production plateau, while the current leaders (China and India) were only beginning their ascent. Since then, the West has been gradually (albeit not entirely consistently) cutting back on the use of coal, while production in emerging economies has been growing to cover the growing energy needs. The trend has become particularly noticeable over the past few years: not only does the transition of European thermal power plants from coal to gas reduce emissions, it also saves money. The fate of coal in the West appears to have been sealed for good. There are, however, exceptions to this trend.

In its attempt to deliver on President Trump’s electoral promise to prevent the “premature closure” of coal fired power plants, the U.S. Department of Energy has proposed compensating electric power plants for their “flexibility” and “predictability” in making the country’s power grid cope with the potential load. At the same time, Trump will have to stimulate the coal mining sector, whose output has decreased by nearly a third over the past ten years due to the depletion of reserves and the associated geological complications. In parallel, the U.S. government will have to exert significant efforts to improve the environmental situation, especially in the view of the observation made by experts that carbon emissions began to decline in 2016 for the first time in many years, primarily thanks to the earlier transition from coal to gas in the country’s power generation.

Figure 1. Leading Coal Manufacturers in 1991–2016, million tonnes

Source: BP Statistical Survey

Until Trump’s victory in the U.S. presidential election, it seemed that global control over coal reserves would inevitably be captured by Asia, where leading consumers have openly declared their intention to increase consumption in the future. However, contrary to the general trend in the West, the new U.S. administration intends to stimulate coal production and use “beautiful clean coal,” as Trump describes it, at home. Russia stands out among the rest of the coal producing countries: in the period 2000–2017, Russia increased coal production by 58 per cent and quadrupled exports, despite the declining domestic consumption.

Russian Reserves

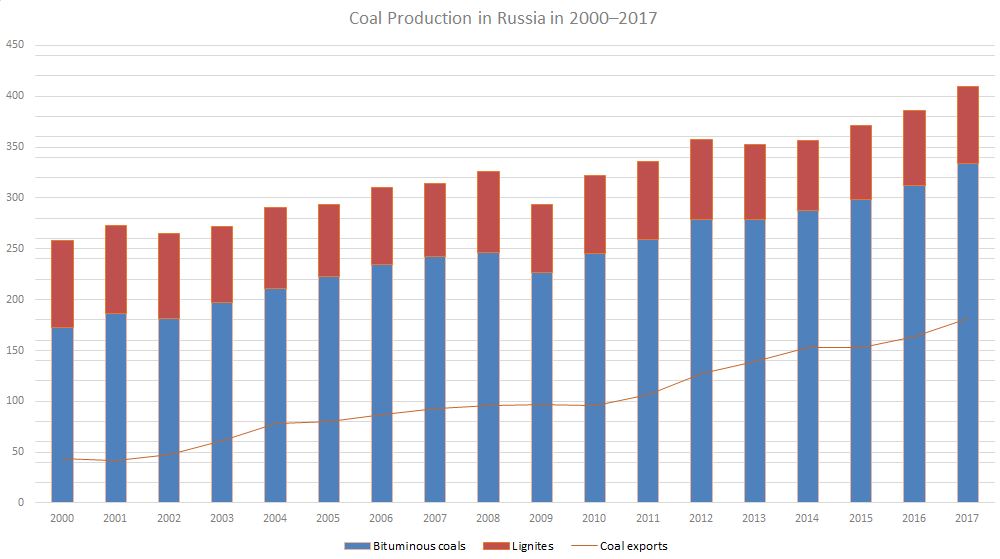

Coal remains in demand in the traditional niches of its use in Russia – power generation and metallurgy. Nevertheless, its share in the country’s overall energy matrix continues to decline. Between 2000 and 2017, domestic consumption fell by 20 million tonnes to 167–168 million (see Figure 2). The use of universally accessible and inexpensive gas in power generation has reduced the scope of use for coal. The housing and utilities sector, for one, is actively replacing coal with by gas and alternative sources of power. This is partly due to the fact coal sells at market prices, while gas prices are regulated by the government.

Russia predominantly mines for bituminous coals: 334 million tonnes of this type of fuel was produced in 2017, which accounts for 81 per cent of all coal extracted. There used to be a certain modicum of competition between the production of bituminous coals and lignites, but the share of the latter in overall production has fallen by 14 per cent to 19 per cent (see Figure 2). Russia’s reserves of all types of coal exceed 274 billion tonnes. Lignites make up more than half of this figure, while bituminous coals account for 43.5 per cent. Coking coal (a type) of bituminous coal accounts for over 18 per cent of total production, with reserves amounting to nearly 50 billion tonnes. The share of anthracite coals is slightly more than 3 per cent.

Figure 2. Coal Production in Russia in 2000–2017

Sources: The Russian Federal State Statistics Service, the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment of the Russian Federation

The prognostic reserves for the most reliable P1 category alone stand at 466 billion tonnes. About a quarter of Russia’s reserves are located in the Kuznetsk Basin, also known as Kuzbass (69.3 billion tonnes), which is mined for high-quality coal with a sulphur content as low 0.3–0.8 per cent and an ash content of just 10–15 per cent. Kuzbass actually has the potential for greater coal production, since its prognostic reserves are many times higher than those already explored. On the other hand, coal bearing pools situated closer to Russia’s Far Eastern ports, including the Southern Yakut and Lena basins in Yakutia, will also be important to the country’s export potential. Russia is not the only coal producer increasing exports to the Asia-Pacific; it is a global trend.

At the same time, Russian will not focus its coal exports on a single geographic region: as the traditional markets disappear, new ones will emerge for Russian companies to occupy quickly thanks to the low production costs and the relatively good quality of the product. The opportunities for exporting coal to Germany may be on the wane compared to the significant peak of 2013–16, although the chance may arise to supply the product to Spain or the eastern coasts of the Mediterranean. Russian coal exports to China and India will grow to match local consumption. In fact, Moscow has already started supplying more coal to China after sanctions were levied on North Korea.

The complete ban coal imports from North Korea marked the end of a number of rounds of sanctions against the country that had started in November 2016. Prior to that, Pyongyang had been allowed to export not more than 7.5 million tonnes of coal per year (or coal worth a total of no more than $400 million). Almost all North Korea’s coal exports went to China. Russian coal producers have taken advantage of this opportunity to strengthen their positions in the Chinese market. Russia exported 25.3 million tonnes of coal to China in 2017, an increase of 37 per cent year-on-year.

As a major coal exporter, Australia (which exported 79.9 million tonnes, in 2017, nearly four times the amount that Russia exported in the same year) could benefit from the situation, but the aftermath of tropical Cyclone Debbie in April 2017 limited the options available to Australian manufacturers. As a result, the highest growth in coal exports to China was demonstrated by Russia and Mongolia (up 28 per cent for the latter). Mongolia increased exports of coking coals to Beijing, while Russia primarily boosted exports of anthracite coals (up 203 per cent year-on-year according to Reuters) – the highest-quality coals, whose reserves are very limited in China.

Coal production and coal exports in Russia are sure to increase with the implementation of major projects, including the production development at the Elginsky deposit. The Energy Strategy of the Russian Federation until 2035 calls for increasing coal exports, primarily to the Asia-Pacific region. The Ministry of Energy’s optimistic scenario suggests an increase in production to 490 million tonnes and an increase in exports to 250 million tonnes in that period. The conservative scenario indicates a prolonged period of stagnation at the current level. The dynamics over the past three years have been positive, so the optimistic scenario has a chance.

Despite the fact that Russia exports significant volumes of coal, it also imports between 20 and 25 million tonnes annually from Kazakhstan for electricity generation purposes in several cities across the Urals. It is cheaper to import coal from Kazakhstan than to organize transportation from the remote regions of Siberia. Over time, the volume of imports will be reduced to a minimum, with coal originating from the Ekibastuz basin to be replaced by Kuzbass coal. The government of Kazakhstan is aware of these plans, and is seeking new markets for its coal.

A Coal-Free Portfolio

The future of coal in Europe is unclear. As gas grows cheaper due to the gradual increase in the number of LNG suppliers and improvements to the regasification infrastructure, the demand for coal in the region is expected to decline at a rate of 8 to 10 million tonnes per year. Not only will gas become competitive in terms of its price, it will also be preferable because of its significantly lower emissions.

Approximately 25 per cent of all electricity produced in Europe comes from coal (this figure has changed by just 3–4 per cent over the past 20 years). Coal is one of the major air pollutants in the European Union. It is no coincidence that almost all the most polluted cities in Europe either consume coal for power-generation purposes or produce it themselves.

In this regard, it is surprising how little has been done within the European Union to minimize the risks linked to coal consumption. Poland, one of Europe’s leading industrial powers, uses coal to generate 80 per cent of all its electricity. The figure stands at around 75 per cent for Estonia and slightly under 50 per cent for the Czech Republic, Germany, Bulgaria and the Netherlands. Several European countries have supported the initiative to gradually decommission coal-fired power plants. The United Kingdom, a leading coal power throughout most of the 19th and 20th centuries, blazed the trail by setting itself the goal of abandoning coal-based electricity generation by 2025.

France intends to abandon the use of coal by 2022; with Italy and the Netherlands set to follow suit, by 2025 and 2030, respectively. However, Europe’s energy locomotive, Germany, is not yet prepared to outline the prospects for its coal industry, even though switching power plants to gas fuel would benefit the country to the greatest extent. Coal-fired power plants produce 40 per cent more emissions than those running on gas to generate comparable volumes of electricity, and 20 per cent more than those running on oil.

A number of investment funds have started to jettison their coal assets, most notably the Government Pension Fund of Norway, which decided in 2015 to divest all of its coal-related assets to the tune of some $1 billion. The Norwegian government declined to take a step further and divest its oil-and-gas assets, which non-governmental organizations had insisted upon, apparently in the belief that the potential profit from holding on to these investments would exceeds the potential risks.

Leading asset management and insurance companies, including Allianz of Germany and Aegon of the Netherlands, are similarly not investing in businesses with any significant profits coming from coal production. There is reason to believe that the trend will spread to other continents over time, although the behaviour of European companies does not affect the situation in Asia or in the United States.

Interestingly, NGOs and environmentalists have been calling on leading companies to abandon all types of hydrocarbon accounts in their portfolios, but thus far the only positive reaction to these calls has been heard exclusively on the coal front. Furthermore, a number of EU giants (Royal Dutch Shell, Total, ENI, Statoil and BP) have publicly hailed the abandonment of coal and expressed the hope that switching to gas will become key to fighting climate change.

The Growing Demand for Coal in Asia

China is the world’s largest producer of coal. It also accounts for over half of global coal consumption, although it will not hold this position forever. To begin with, further growth in demand for coal in China will be hampered by the steps taken by the government in 2016–2017 to radically reduce air pollution in the cities. The 13th five-year plan calls for reducing the share of coal in the country’s energy consumption structure to 58 per cent (compared to 64 per cent in 2015) and switching power generation facilities in major cities from coal to gas. The transition is going to be painful (many of China’s northern provinces had to re-introduce coal this past winter due to gas shortages), but the authorities will not budge.

China will certainly continue to be the largest consumer of coal. However, experts believe that country’s consumption has already reached a plateau and will remain stable until about the mid-2020s, after which the inevitable decline will follow. This means that, with the gradual reduction of coal use in the West and China, India will become the most promising market. The International Energy Agency predicts that India will see its coal consumption grow by 135 million tonnes annually by 2022, more than the rest of Asia and Africa combined. However, even India’s coal consumption is eventually expected to peak (some expect this to happen in 2027), after which Indian investors will turn to renewable energy sources, primarily solar power.

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and other Southeast Asian countries are also likely to emerge as the main drivers of global demand for coal in the years to come. Russia, owing to its relative geographic proximity to the region and the existence of the requisite infrastructure, is in a position to boost its presence in the traditional Chinese, Japanese and South Korean markets and also carve a niche in newly emerging marketplaces. In the meantime, coal supplies to Europe and other developed economies will continue, not least because of the anticipated hiccoughs in the transition to clean energy generation in those countries: in certain instances, coal will prove more profitable than gas. Overall, however, coal market players need to brace themselves for the beginning of an irreversible decline of the industry somewhere around the year 2040.