Today's debates on future economic relations between Russia and the West focus on the projected effects of various sanctions and possible market fluctuations, just as they did during the 2008 Georgian-Ossetian conflict. However, the current situation involves a much more complex, and ambivalent, entanglement of circumstances in international economic relations than was the case six years ago. On the one hand, European business circles realize the scope of economic cooperation with Russia, and representatives of companies, entire industries and the financial sector have ruled out long-term sanctions against Moscow. On the other hand, increasingly militant political rhetoric, the pace of which is set by the United States and the European Commission, cannot but affect rational business thinking. The Crimean referendum and the potential for flashpoints that spark conflict to appear elsewhere in Ukraine necessarily mean a prolonged setback to Russian-European economic cooperation and partial freezing of Russian-American economic cooperation. But the main question is not how long this cooling of relations will last, but if there are real conditions for fundamental shifts in the spheres of economic influence, under different scenarios for the formation of a new Ukrainian state structure.

Despite Ukraine’s terrible plight – precariously balanced on the brink of default – and its peripheral role in global economic processes, the country is an important functional element in the dynamic mechanism of globalization. Its significance becomes apparent as representatives of the international community express conflicting positions on today's crisis. These differences testify not only to rational dualism and the conflict of interests between the different segments of the establishment, but also to the fact that the world is undergoing profound global economic change, which, in the wake of events in Ukraine, is gaining momentum.

The first economic aspect of the Ukrainian crisis is the energy policy. Ukraine has long been at the center of a debate on the diversification of gas supplies to Europe and, consequently, on the reduction of Europe’s dependence on Russia, and it is no accident that it gets so much attention on analysts’ energy maps. It is assumed that instability in Ukraine forms a permanent negative background for Russian gas exports. At the same time, it sparks particular anxiety in European countries, which want more stable and reliable energy resources delivery, not the withdrawal of Russian companies from the market.

In this respect, the South Stream pipeline, which bypasses the “zone of instability,” seems strategically more reliable to European investors and consumers. During the escalation of the Ukrainian crisis, lobbying groups in the United States immediately intensified their activities to railroad through the Obama administration the construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals to extend a helping hand to Europe and encourage it to abandon the South Stream project. However, this seems too costly, while the figures, in contrast, indicates the European desire to minimize dependence on LNG and increased orientation on traditional forms of delivery.

Through 2015 the EU has room for maneuver, since it seems to have sufficient gas reserves to last a year, and the European Commission will undoubtedly use this time to bargain hard with Russia over the gas price and Gazprom structure, using the situation in Ukraine as a trump card. It seems quite probable that Russia will agree to export concessions, such as mitigating its position on the EU Third Energy Package in exchange for retaining its tough stance on Ukraine.

The situation can also be viewed from a different angle. In 2013, Gazprom launched a policy of systematic gas price reduction for EU member-states. There are indications that, in order to strengthen its position Russia, it might choose to pursue a flexible pricing policy on a larger scale, which neither the U.S., nor the Maghreb, nor Iran can afford. Therefore, even if the European Union were to enact all phases of the three-stage sanctions roadmap, they would affect certain categories of goods and be limited in time, in order not to impact the foundations of energy cooperation.

The second track, which is less evident but more comprehensive in scope, is the global, latent change in zones of economic influence. The world has reached its historic peak in terms of the market economy’s territorial distribution, but development models are becoming increasingly polar. Therefore, the need to build a new world order and a new system of international relations that politicians, businessmen, diplomats and experts have anticipated since the end of the Cold War, has become increasingly dependent on market factors and transnational competition.

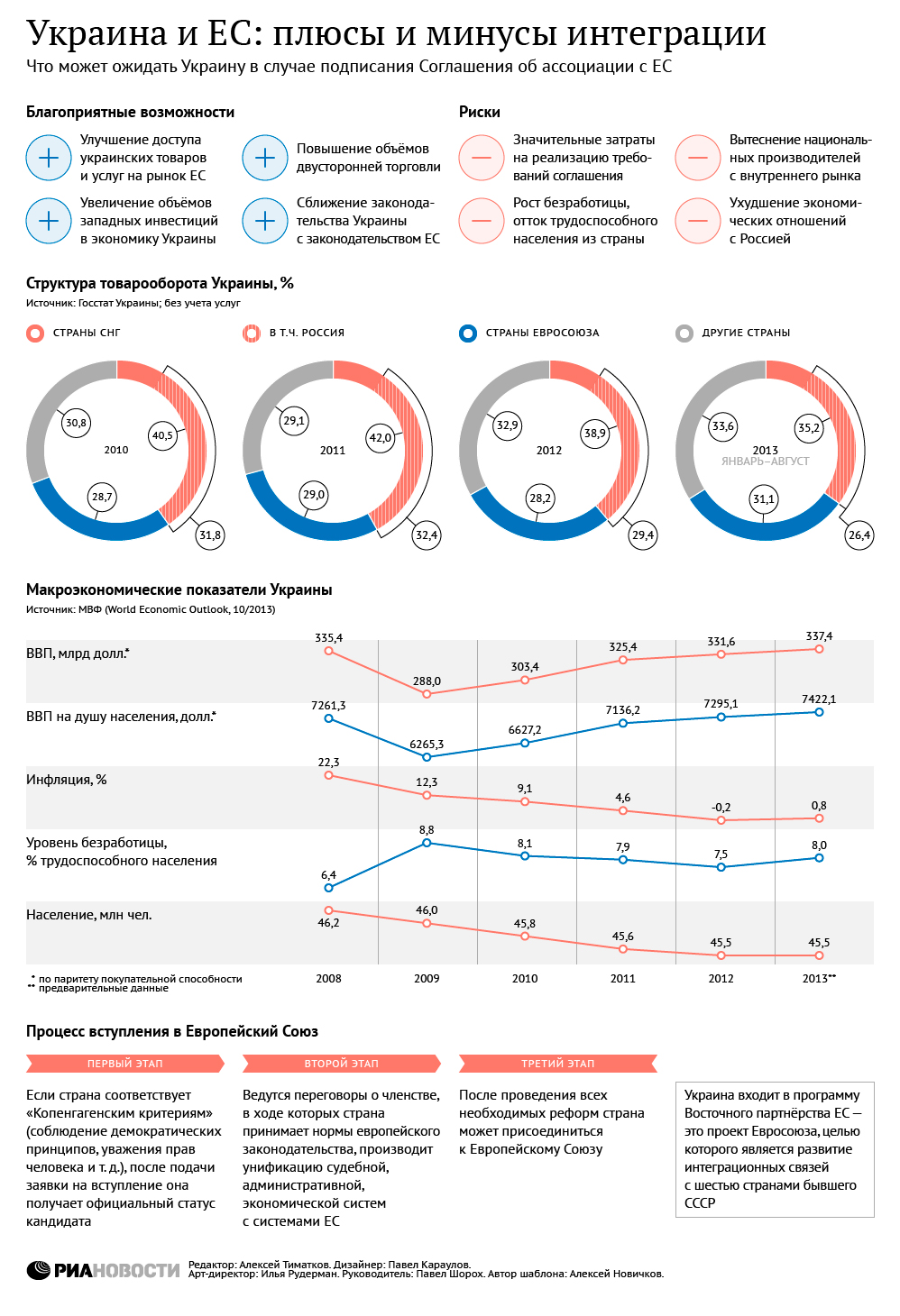

Ukraine found itself in the thick of the geo-economic confrontation between the two trade areas, closing in on it from either side. Although the Customs Union is a new and institutionally weak grouping, it is clear that an attempt at reformatting the economic space could arouse serious concern among European and American proponents of West-to-East market expansion. It should be noted that at the heart of the Ukrainian crisis lay not the territorial differentiation of the country, the Russian language law, corruption among Yanukovych administration officials, or even economic stagnation, but the decision to suspend signing of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. It was this that acted as a catalyst for the coup in Kiev.

It is the geo-economic processes underway in Eurasia today that largely account for the polarized discussions about reconfiguring the political space and the vectors of modernization, and which fuel the return of concepts such as “civilization” and “barbarism”, “development model” and “a special way” to the political debate. Ukraine has become a testing ground for the new liberal Europeanization project and an ideological battleground for key distinctions in political and economic values, identity, and culture. The shortsightedness of which Yanukovych was accused, is now in fact, an attempt to reap the benefits from each of these two, competing, integration processes. However, he miscalculated their impact and escalating fundamental contradictions (outlined by Stefan Füle, the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and Neighborhood Policy).

In addition, the Ukrainian crisis will inevitably revive latent processes in the former Soviet space, and intensify the debate about new paradigms of regional security and risk management. It is not by chance that the situation in Ukraine is constantly and closely watched by China, a country that faces similar and so far latent geo-economic transformations in the Asia-Pacific Region (APR) that are taking place against a backdrop of increased differences between ASEAN +3 integration projects and the American alternative of a Trans-Pacific Partnership. The position of the ruling elites in most South Asian countries from Vietnam to Indonesia is very similar to that observed in the post-Soviet space. In a nutshell, it can be described as indecision and anxiety caused by increased regional tensions and uncertainty of the main actors’ roles – primarily, the United States, China, India, Japan in Asia Pacific, and Russia, the United States, the European Union, and China in the post-Soviet space.

But competition over economic transformation vectors exists not only between the nominal West and the nominal emerging market blocs (be they BRICS, G20 or other formats). It is also seen in the heterogeneous West. The United States spares no effort in trying to retain its global geo-economic position, but to succeed it needs the support of traditional partners, i.e. Western Europe, Japan, the Gulf monarchies, and a number of Latin American countries. However, the U.S. concept of geo-economic zones faces not only open adversaries (China, for example), but also sows doubt among traditional allies.

The current politically charged environment certainly plays into Russia’s hands. No wonder that Vladimir Putin, in his speech on March 18, 2014 addressed Germany – the key European economy, trying to maintain a balance against the background of intensified intra-European and Atlantic economic differences.

In the wake of the information boom accompanying the current crisis, Russia, like never before in the past 24 years, will need a circumspect foreign economic strategy, purposeful work with European, Asian and, in the longer run, Latin American business circles, as well as engagement with public opinion in these regions. It is important for Russia not so much to demonstrate its military power as to strengthen its image as a guarantor of economic security. Otherwise, the country may once again miss an historic opportunity. This is a unique opportunity, not only for Russia but also for emerging markets, since they lack a consolidated and confident vision of the new economic space. Current developments make one thing certain: the dynamic events in Ukraine have, perhaps, given the most powerful impetus to reformatting the Eurasian economic space that the area has seen since the end of the Cold War.