The Russian initiative to develop a security system in Eurasia is going through one of its most difficult stages. It received a powerful start, having been put forward at the highest political level, by President Vladimir Putin. Russian diplomacy has managed to launch a dialogue process around the initiative with the largest powers in Eurasia, with partners in neighbouring countries. In the logic and spirit of the initiative, new bilateral agreements on security issues are emerging.

The new idea does not yet have a long history and inertia working in its favour. At the same time, resistance from the environment will grow—an attempt to torpedo it from political opponents both at the level of ideas and practical issues.

The first question that arises in the dialogue about the new system is: why doesn’t Moscow immediately “put the folder on the table”? The Russian approach clearly stands out from this practice. Moscow has voiced the idea in the form of a problem statement and a starting point. It invites others to become the authors of the project. Instead of directives handed down “from above”, a space is created for dialogue and creativity. We have our own opinion. But we want to work on it together with our friends and like-minded people. In itself, it creates a communicative environment, a narrative, a space for interaction.

The second question: Does Moscow want to use the idea of Eurasian security to create a coalition against Washington, involving the countries of the global majority? More no than yes. Russia understands well that each country has its own relations with the United States. An attempt to drive a wedge between them and the United States is doomed to failure in advance, and therefore it is not included in the project. Russia's experience as a key player that has called the Euro-Atlantic realities into question is important for the rest. An extra-regional hegemonic player is redundant for the architecture of such a complex continent, unlike the other players.

The third question is: why doesn’t Russia include ideological principles in the architecture of Eurasian security? First of all, Russia has the Soviet experience. Russia has learned a lesson: it is simply impossible to fit the complexity of international relations into a uniform ideological picture, no matter how rational it may seem. Another reason is the well-founded suspicion that modernist ideologies and principles yield to postmodernist ones under the influence of various factors. We are increasingly dealing not only (and perhaps not so much) with liberalism as with its image, its simulation. Liberalism as a rationalist ideology is not alone within its problems. The problem is systemic. This means that it is impossible to base the new architecture of Eurasian security on a rigid ideological platform.

The fourth question is whether it is possible to fit all the diversity of the continent's countries into one system. Diversity is an obvious problem on the path to discipline and efficiency. The way out is to take the principle of diversity as a given, accept it as an objective reality, and not chase discipline and efficiency in the short term. Respect for diversity will sooner or later yield results. Authority and trust are more effective than domination and coercion.

Finally, the fifth question. What is to be done with the anarchic nature of international relations? The Eurasian continent is not only a storehouse of resources and material wealth, but also of conflicts and dividing lines. Russia itself is part of an anarchic system, and sometimes reacts harshly to external challenges. Russia has a rich heritage of survival in an extremely hostile environment and resolves survival issues through force. We are not angels, and therefore we cannot teach others from above. What we can do is think about a better future and create it together, instead of relying on of others.

The Russian initiative to develop a security system in Eurasia is going through one of its most difficult stages. It received a powerful start, having been put forward at the highest political level, by President Vladimir Putin. Russian diplomacy has managed to launch a dialogue process around the initiative with the largest powers in Eurasia, with partners in neighbouring countries. In the logic and spirit of the initiative, new bilateral agreements on security issues are emerging.

To use a space exploration analogy, we can state that the first stage of the rocket worked flawlessly. However, ahead is the launch of the second stage and the initiative's entry into the necessary political orbits. The key problem with this stage is the creation of detailed principles regarding the new security architecture in dialogue with Russia's partners on the continent, their enunciation in specific agreements, and their subsequent development in the form of international institutions. We are talking about the most difficult stage, both in a conceptual and a political sense. The new idea does not yet have a long history and inertia working in its favour. At the same time, resistance from the environment will grow—an attempt to torpedo it from political opponents both at the level of ideas and practical issues.

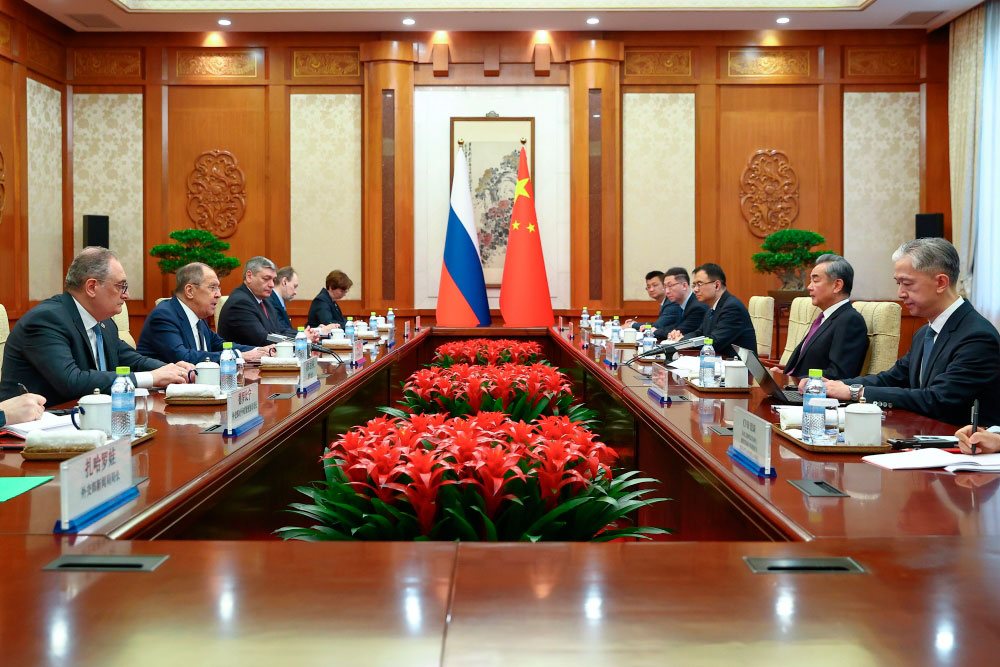

The first question that arises in the dialogue about the new system is: why doesn’t Moscow immediately “put the folder on the table”? Why, following the initiative of the Russian leader, are there no pre-prepared transcripts in the form of a draft of fundamental principles and mechanisms that should be made public? This approach contrasts starkly with those issued amid Western preparations—they are often accompanied by a carefully verified portfolio of specific roadmaps and action plans that follow the statements of leaders. The Russian approach clearly stands out from this practice. Moscow has voiced the idea in the form of a problem statement and a starting point. It invites others to become the authors of the project. Instead of directives handed down “from above”, a space is created for dialogue and creativity. We have our own opinion. But we want to work on it together with our friends and like-minded people. Two recent documents are indicative. The first is a joint-statement by the CIS foreign ministers on the principles of cooperation in ensuring security in Eurasia. The second is the Joint Vision of the Eurasian Charter of Diversity and Multipolarity in the 21st Century, presented by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and his Belarusian counterpart Maxim Ryzhenkov in Minsk. Can they be considered a completed concept of the new architecture? Not yet. Can they be considered part of a "brainstorming" and the joint development of an approach? Certainly. Such iterations can and should be repeated together with the widest range of partners in Eurasia. In itself, it creates a communicative environment, a narrative, a space for interaction.

The second question: Does Moscow want to use the idea of Eurasian security to create a coalition against Washington, involving the countries of the global majority? More no than yes. Russia understands well that each country has its own relations with the United States. They are determined by huge volumes of trade, diasporas, participation in supply chains, and other interests. An attempt to drive a wedge between them and the United States is doomed to failure in advance, and therefore it is not included in the project. But something else is also true. The European security system has failed to become inclusive, thereby removing the prerequisites for any conflicts based on the principles of equal and indivisible security. The European, or more precisely the Euro-Atlantic system, remains closed and vertical. It has its own democratic mechanisms, but is objectively subordinated to the will and leadership of the United States. A large-scale conflict in the centre of Europe has been the visible result of the accumulated imbalances of the Euro-Atlantic system. This is an important lesson for the creation of any new architecture. Russia's experience as a key player that has called the Euro-Atlantic realities into question is important for the rest. An extra-regional hegemonic player is redundant for the architecture of such a complex continent, unlike the other players.

The third question is: why doesn’t Russia include ideological principles in the architecture of Eurasian security? The US and the collective West have them in the form of a rationalistic and modernistic liberal model. They promote not only their own interests on the external contour, but also such normative and political-philosophical principles as liberty, democracy, free market competition, human rights, etc. Here, Moscow, judging by everything, has several reasons for exercising caution. First of all, Russia has the Soviet experience. From its collapse, which Putin has called the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the last century, Russia has learned a lesson: it is simply impossible to fit the complexity of international relations into a uniform ideological picture, no matter how rational it may seem. The result will sooner or later be the emasculation of principles, their devaluation, and then the erosion of interests in favour of dubious and speculative schemes. Another reason is the well-founded suspicion that modernist ideologies and principles yield to postmodernist ones under the influence of various factors. We are increasingly dealing not only (and perhaps not so much) with liberalism as with its image, its simulation. The tension between the image and real life leads to short circuits. A separate question is whether we’re addressing the properties of modern ideology or whether only liberalism experiences such problems. Liberalism as a rationalist ideology is not alone within its problems. The problem is systemic. This means that it is impossible to base the new architecture of Eurasian security on a rigid ideological platform.

The fourth question is whether it is possible to fit all the diversity of the continent's countries into one system. It is one thing to voice an idea, and quite another is to create a working mechanism. Western institutions, despite all their shortcomings in the form of hierarchy and relative secrecy, still represent a well-organized machine that combines different formats and substantive agendas: the rigid version of NATO and the bureaucratic EU are combined with flexible and temporary “troikas”, “quads” and other sets, in which non-Western players are actively involved. However, the process of such involvement does not go very far. In other words, diversity is an obvious problem on the path to discipline and efficiency. The way out is to take the principle of diversity as a given, accept it as an objective reality, and not chase discipline and efficiency in the short term. Respect for diversity will sooner or later yield results. Authority and trust are more effective than domination and coercion.

Finally, the fifth question. What is to be done with the anarchic nature of international relations? A sceptic will point out that everyone is ready to support good principles and wishes such as diversity, equal and indivisible security, sovereign equality, etc.—but in reality, everyone will promote their own interests. The Eurasian continent is not only a storehouse of resources and material wealth, but also of conflicts and dividing lines. Russia is unlikely to be able in the foreseeable future to overcome the splits and unite the world majority, even within the borders of Eurasia. However, it is capable of providing forward momentum, showing an alternative. Russia itself is part of an anarchic system, and sometimes reacts harshly to external challenges. Russia has a rich heritage of survival in an extremely hostile environment and resolves survival issues through force. We are not angels, and therefore we cannot teach others from above. What we can do is think about a better future and create it together, instead of relying on of others.

First published in the Valdai Discussion Club.