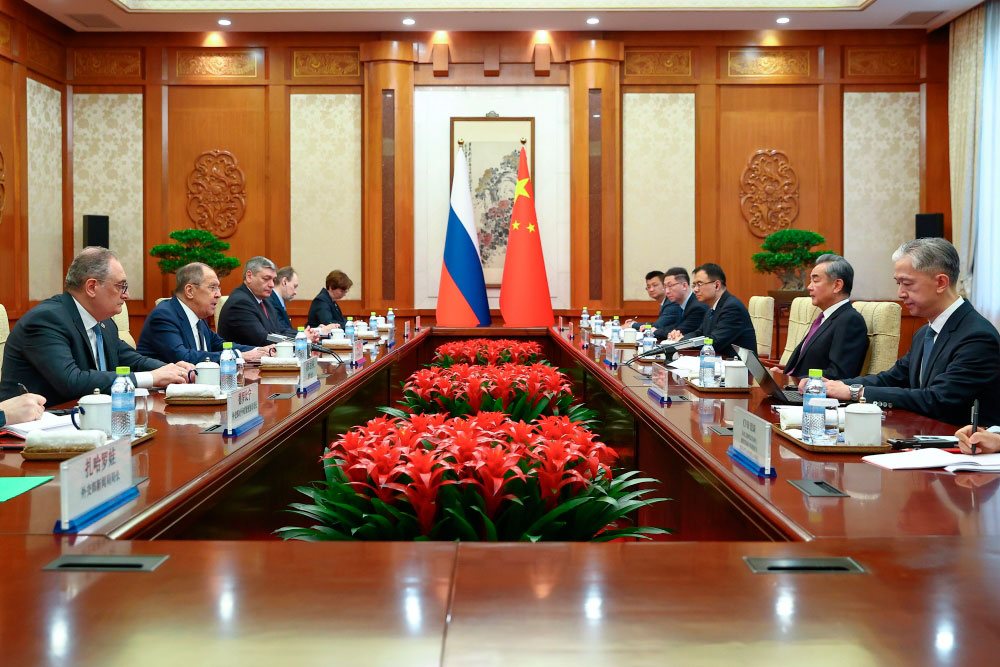

Interaction with China remains one of the most stable and reliable elements for Russia’s foreign policy. The trusting relationship between the leaders of the two countries contributes to the development of a political dialogue in regular high-level meetings and joint statements. Strategic interaction stimulates trade and economic partnership.

At first glance, the dynamics of Russian-Chinese interaction confirm the persuasiveness of structural realism—a theory that points to the primary importance of the structure of international relations as they relate to individual subjects of global processes. However, when answering the question of what factors can contribute to the development of constructive interaction between two players comparable in power and international influence, realism pays less attention to how to maintain such interaction in the long term. In other words, how can competition be avoided in the future?

A partial answer to this question is offered by constructivism, which points to the dependence of the model of behaviour towards the counterparty on the perception of the latter. In speeches, the Russian leadership regularly points out that maintaining strategic relations with the PRC fully meets Russia’s interests, but mistrust of China at the level of business circles and the general population persists. Overcoming it requires a general deepening of mutual understanding and/or debunking of negative attitudes about the partner.

Overcoming stereotypes, in turn, seems to be a feasible task to a greater extent, since it can take place both in communication and in practical fields. The narrative of Russia’s dependence on China, spread by opponents of the Moscow-Beijing partnership, can be refuted by diversifying bilateral trade and other economic and financial measures, which are already being worked on. A truly favourable historical moment, as it seems, is developing today for working with another stereotype—about the inevitability of competition between Russia and China as two great powers in adjacent regional spaces.

The Russian-Chinese partnership, despite the stability of the political dialogue and the rapid growth of mutual trade indicators, will be able to acquire systemic significance for the multipolar world order only if it is used to form and develop multilateral institutions. First of all, this concerns Eurasia—the space in immediate proximity to Russia and China. The most optimal format for dialogue on issues related to both the formation of the Eurasian security architecture and the economic development of the Eurasian region is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

The growth of global conflict has provoked the erosion of many of the region’s governments, including with respect to non-proliferation and combating organised crime. Accordingly, the polylogue in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation space can no longer and should not be limited to the fight against the “three forces of evil” (separatism, terrorism and extremism). At the same time, a large number of initiatives aimed to solve economic problems coexist in the organisation’s space: this includes the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the “5+1” formats, the Belt and Road initiative, and the North-South ITC aimed at solving problems in the area of regional connectivity, etc. Accordingly, conditions have been formed in the Eurasian space for transforming the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation into a platform for discussing models of multilateral integration of all the aforementioned regional development projects, into a more modern mechanism for building “sustainable security” with multiple dimensions: from military-political to socio-economic.

The coordination of the positions of Moscow and Beijing on the formation of the regional security architecture and a new model for the SCO’s functioning is becoming a fundamental issue. This again returns us to the problem of communication and mutual understanding at the bilateral level. This means that work on developing economic cooperation should not replace dialogue with each other, the worldview of partners and their interests.

Interaction with China remains one of the most stable and reliable elements for Russia’s foreign policy. The trusting relationship between the leaders of the two countries contributes to the development of a political dialogue in regular high-level meetings and joint statements. Strategic interaction stimulates trade and economic partnership. Even under sanctions, by the end of 2023, bilateral trade turnover exceeded USD 240 billion. In 2023–2024, Chinese companies actively filled the niches left after the departure of Western suppliers in the market for cars and spare parts, electronics, construction materials, etc. Russian businesses, in turn, sought out new markets in the PRC.

At first glance, the dynamics of Russian-Chinese interaction confirm the persuasiveness of structural realism—a theory that points to the primary importance of the structure of international relations as they relate to individual subjects of global processes. Russia’s “pivot to the East” in the context of the conflict with the West and the underlying redistribution of power potentials between old and new great powers generally confirms the relevance of external explanations for the creation of various partnerships. However, when answering the question of what factors can contribute to the development of constructive interaction between two players comparable in power and international influence, realism pays less attention to how to maintain such interaction in the long term. In other words, how can competition be avoided in the future?

A partial answer to this question is offered by constructivism, which points to the dependence of the model of behaviour towards the counterparty on the perception of the latter. In speeches, the Russian leadership regularly points out that maintaining strategic relations with the PRC fully meets Russia’s interests, but mistrust of China at the level of business circles and the general population persists. Overcoming it requires a general deepening of mutual understanding and/or debunking of negative attitudes about the partner.

Deepening mutual understanding is largely a communicative practice. On the one hand, communication is a favourable tool for strengthening partnerships with the Chinese. Chinese culture, including diplomatic culture, pays more attention to words and images than, for example, American culture. China’s foreign policy discourse is filled with elegant formulations that can be perceived as signals of Beijing’s non-confrontational intentions. China characterizes its dialogue with Russia as interaction between great powers of a “new type”, “relations of comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation entering a new era”, “friendship that is passed down from generation to generation and will never become hostility”, and “a more advanced form of interstate interaction compared to the military-political alliances of the Cold War era”. On the other hand, from a cultural and historical point of view, Russia and China belong to different civilisations. Among decision-makers in Russia, there are far fewer people who are Sinologists and orientalists, than it is required given the new international political conditions. Among business circles and the general public, there are even fewer specialists with knowledge of the region. It is impossible to increase their number several-fold in a short period of time, since the inertia of Westernised behavioural models and business practices in Russian society is very strong. Accordingly, there are gaps at all levels of Russian-Chinese dialogue that could make an additional contribution to improving mutual understanding and communication. The problem, however, is not only on the Russian side. The complexity of Chinese foreign policy discourse leads to the fact that it is not perceived as meaningful or credible.

As a result, deepening mutual understanding by developing a single foreign policy glossary remains an asterisked task for both Moscow and Beijing.

Overcoming stereotypes, in turn, seems to be a feasible task to a greater extent, since it can take place both in communication and in practical fields. The narrative of Russia’s dependence on China, spread by opponents of the Moscow-Beijing partnership, can be refuted by diversifying bilateral trade and other economic and financial measures, which are already being worked on. A truly favourable historical moment, as it seems, is developing today for working with another stereotype—about the inevitability of competition between Russia and China as two great powers in adjacent regional spaces. The Russian-Chinese partnership, despite the stability of the political dialogue and the rapid growth of mutual trade indicators, will be able to acquire systemic significance for the multipolar world order only if it is used to form and develop multilateral institutions. First of all, this concerns Eurasia—the space in immediate proximity to Russia and China. The most optimal format for dialogue on issues related to both the formation of the Eurasian security architecture and the economic development of the Eurasian region is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

The SCO was conceived as a forum for communication between Russia, China and the five Central Asian states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), dedicated to maintaining regional security and creating conditions for the peaceful development of the countries, as well as overcoming threats of terrorism, extremism and separatism. Over its more than twenty-year history, the organisation has obviously outgrown its original mandate both geographically and functionally. Today, the organisation includes all major Eurasian powers, namely Russia, China, India, Iran and Pakistan. With the accession of the Republic of Belarus in 2024, the western border of the association also shifted.

All these states have their own ideas about threats to national and regional security. Moreover, they can even classify their SCO partners as a destabilising factor. The situation in the field of international security as such has also changed. The growth of global conflict has provoked the erosion of many of the region’s governments, including with respect to non-proliferation and combating organised crime. Accordingly, the polylogue in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation space can no longer and should not be limited to the fight against the “three forces of evil” (separatism, terrorism and extremism). At the same time, the SCO consists of developing countries. When interacting with the Central Asian countries in the “5+1” format [1], China emphasises the problems of their development: poverty, social inequality, access to natural resources (including traditional and non-traditional energy sources), and weak infrastructure.

At the same time, such problems are not only characteristic of the Central Asian states. To one degree or another, most of the countries—new SCO members—face them, with the possible exception of Belarus. At the same time, a large number of initiatives aimed to solve economic problems coexist in the organisation’s space: this includes the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the “5+1” formats, the Belt and Road initiative, and the North-South ITC aimed at solving problems in the area of regional connectivity, etc. Accordingly, conditions have been formed in the Eurasian space for transforming the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation into a platform for discussing models of multilateral integration of all the aforementioned regional development projects, into a more modern mechanism for building “sustainable security” with multiple dimensions: from military-political to socio-economic.

At the same time, the scaling of the SCO mandate will also inevitably experience the consequences of communication difficulties not only between Russia and China, but also between India and China and India and Pakistan.

Mutual trust between parties with a long history of conflicts cannot be built immediately. However, in the conditions of global turbulence, it is also impossible to risk stability in Eurasia, which means there is no time to wait until mutual trust is formed naturally as a result of a gradual increase in the number and intensity of common practices. For this reason, the coordination of the positions of Moscow and Beijing on the formation of the regional security architecture and a new model for the SCO’s functioning is becoming a fundamental issue. This again returns us to the problem of communication and mutual understanding at the bilateral level. Since 2015, Russia and China have not formed a common vision of the idea of a Greater Eurasian Partnership put forward by Russia, just as they have not found a model for the confluence of two national initiatives—the EAEU and the Belt and Road.

Establishing communication in Russian-Chinese relations via the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation space in order to maintain constructive, rather than competitive interaction between members does not imply the development of universal ideologies. This is not only impossible, but also unnecessary in a multipolar world. At the same time, developing a new, understandable language of “sustainable security” in Eurasia, thanks to which everyone will be able to contribute to solving and anticipating common problems in their own way, is necessary. This means that work on developing economic cooperation should not replace dialogue with each other, the worldview of partners and their interests. Thus, the “new era” of multilateral cooperation in Eurasia will need not only cooperation between great powers of a “new type”, but also “new thinking” in general. This is, first of all, the task of harmonizing the dialogue between Russia and China.

First published in the Valdai Discussion Club.

1. Similar problems within the “5+1” format with the Central Asian countries are raised, for example, by the European Union. This once again confirms that Russian-Chinese partnership in the region is necessary to prevent competition between many centres of power in Eurasia.