Ankara’s strategic goal is to establish a safe zone stretching from Idlib to the border with Iraq. Alongside the tasks of protecting Turkey from attacks of the PKK and its branches, the “buffer”, if and once created, could serve as a safe haven for Syria’s IDPs, who fled from al-Assad’s government; they should not be allowed to enter Turkey. Additionally, plans involve bringing back into that area some of those Syrian refugees who are already in Turkey. On the eve of the 2023 Turkish elections, moving some refugees into Syria could earn points for Recep Erdogan and his party (AKP).

Ankara can count on some trump cards in its game with Moscow. Maybe, as in 2018 and in 2019, it will succeed in obtaining Moscow’s favorably neutral stance. It may use such “aces up its sleeve” as re-opening an air corridor through Turkey into Syria that Turkey closed on April 23; or else, it may block NATO warships’ passage into the Black Sea no matter how hard NATO tries to push Turkey into revoking its prohibition under various pretexts. Finally, another trump card may be Turkey’s refusal to accede to anti-Russian sanctions.

In the current situation, a conflict with Turkey may turn out to be too costly for Moscow, while direct opposition to Turkey’s plans (primarily if Damascus insists on it) may result in Ankara changing its approaches to the detriment of Russia. However, given Russia’s engagement in hostilities in Ukraine, Turkey can achieve its goals in Syria despite obstacles from Moscow and Damascus. Turkey’s military potential allows for that, especially if it decides to play an all-or-nothing game with the U.S.

It would be expedient for Russia to draw its “red lines” for Turkey. First, it is unblocking M4 route. Any Turkish military action should not cross this “red line” (M4 route), endangering communications via this route, since it is strategically important for Damascus as it essentially integrates Syria along the west-east axis.

In case Ankara launches a military operation without complying with the terms on M4 in Idlib, it may cost Russia major reputational losses in the eyes of its Syrian ally, and these losses are to be avoided. The U.S. may also suffer similar losses as it assumes responsibility for supporting the SDF, calling it America’s close ally. After the U.S. has essentially fled Afghanistan, another such case will result in the U.S. Middle Eastern allies totally losing confidence in America as a security guarantor. Washington should not be stripped of its “crown of alliance” with the SDF as it may ultimately prove a “crown of thorns.”

On the other hand, the U.S. is likely to consent to Turkey conducting such an operation in the end. First, it will not endanger the existence of the SDF, it will only expand the safe strip along the border; second, such a sacrifice on the part of Washington may prompt Turkey to unblock Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO.

At its May 26 meeting, Turkey’s National Security Council (NSC) announced it was necessary to go on with current and prospective operations at the country’s “southern borders” to ensure Turkey’s security. Turkey’s NSC stressed that such operations are not directed against the sovereignty of its neighbors (likely a reference to Syria and Iraq).

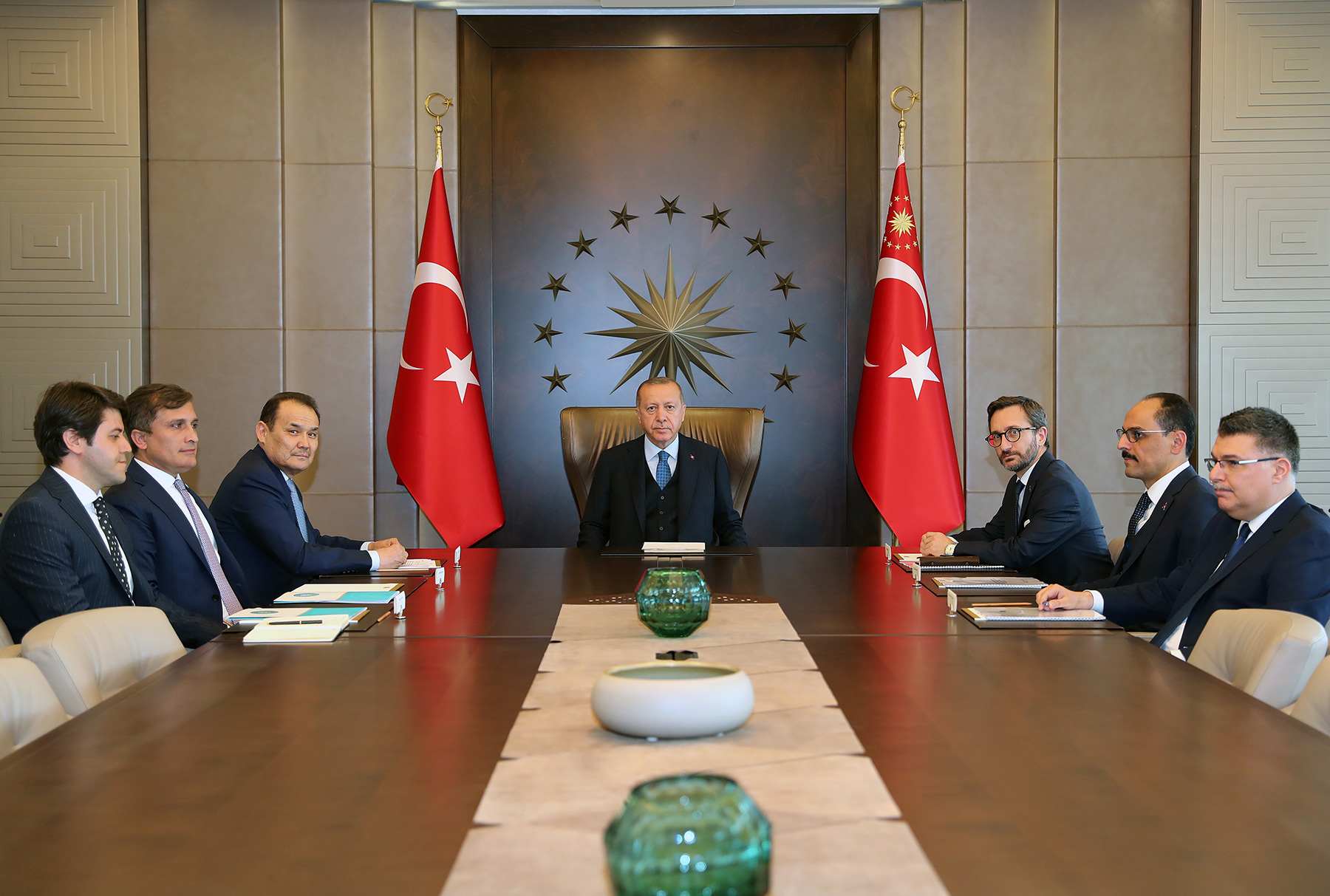

There is little doubt that a “prospective operation” means preparing for a military campaign against the U.S.-supported “Syrian Democratic Forces” (SDF), whose backbone is formed by the radical left-wing People’s Defense Units (YPG) affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—Turkey put it on the list of terrorists. This is what Turkey’s President Recep Erdogan said on May 23.

Turkey’s leader articulated his threats as Ankara attempts to block Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO, since these states support the PKK. Therefore, Ankara is apparently ready to complete its counter-terrorist campaign that is now moving beyond military efforts and is transitioning, among other things, into a political plane of discussions on Euro-Atlantic platforms. Such a “comprehensive approach,” including putting pressure on the PKK’s sponsors among the bloc’s potential members, could also affect and exacerbate Turkey’s already complicated relations with those of its allies from the North Atlantic alliance that continue to support SDF/YPG units in Syria (these are primarily the U.S., France, and the Netherlands).

Rolling out the “Turkish buffer”

Turkey previously ran several operations against Kurdish left-wing radical units in Syria. While Operation Euphrates Shield (2016–2017) was mainly aimed against ISIS (although it did affect some Kurdish territories, for instance, Jarabulus), Operation Olive Branch (2018) and Operation Source of Peace (2019) were directed exclusively against the SDF.

The latter operation in the fall of 2019 was made possible by the inconsistent approach of the Trump Administration: first, he announced U.S. troops’ withdrawal from Syria, thereby opening a window of opportunity for Turkey’s advance in the areas that the U.S. left, then he “changed his mind,” and U.S. military presence remained in the northeast of Syria, in the eastern areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) that is essentially the SDF’s political umbrella. Russian military police units and Syrian border guards moved into the AANES’ western areas pursuant to a memorandum Vladimir Putin and Recep Erdogan had signed in Sochi.

U.S. diplomats led by former Vice President Mike Pence demanded that Ankara cease fire, while Trump threatened to “totally destroy and obliterate” Turkey’s economy should Turkey’s military and its allies from the Syrian National Army (SNA), an opposition force, continue their attacks.

President Joe Biden is even more “pro-Kurdish” than his predecessor—despite the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq, the issue of withdrawing from Syria’s northeast was never raised under the Biden Administration. The current administration in Washington is also more consistent in looking after the interests of its SDF allies. In the fall of 2021, Washington assumed a very harsh stance, ruining Turkey’s plans to conduct another such operation.

At the same time in the fall of 2021, Moscow, which had also cooperated with the SDF, found itself on the same side as Washington, letting Ankara know that Russia considered such steps to be unacceptable. In particular, back then, Mi-8 AMTSh and Ka-52 Alligator attack helicopters and Su-35S fighters were redeployed at the airbase in Qamishli in Northeast Syria (the U.S., still being in control of the air space over the northeast, opened an air corridor for them). At the same time, Russia’s attempts to force Kurdish units to engage in talks with Damascus failed. The SDF kept their military ties with the U.S. and did not intend to sever them, while asking Russia for additional security guarantees. After February 24, amid Russia–U.S. relations essentially severed, this line of conduct assumed by the SDF will hardly strike a chord with Moscow.

Currently, Russia is not so unequivocally set against Turkey’s possible operation in Syria, and although rumors of Russia’s troops being possibly withdrawn from the bases in Northeast Syria have not so far been confirmed, their circulation suggests this scenario is within the realm of what is possible. There is evidence of the U.S. deploying its troops in those areas they left in 2019, which creates a certain zebra striping of Russian and American troops. U.S. troops deploying at their old bases may also indicate that the U.S. is weighing up the possibility of Russia withdrawing from the presumed areas of Turkey’s future operation and the U.S. wants to be on the safe side.

Four scenarios

Ankara’s strategic goal is to establish a safe zone stretching from Idlib to the border with Iraq. Alongside the tasks of protecting Turkey from attacks of the PKK and its branches, the “buffer”, if and once created, could serve as a safe haven for Syria’s IDPs, who fled from al-Assad’s government; they should not be allowed to enter Turkey. Additionally, plans involve bringing back into that area some of those Syrian refugees who are already in Turkey. On the eve of the 2023 Turkish elections, moving some refugees into Syria could earn points for Recep Erdogan and his party (AKP).

If Ankara ultimately makes the decision to conduct a military operation, there are four possible scenarios.

The first scenario — Turkey and its SNA allies attack Tell Rifaat. This SDF-controlled enclave emerged back in 2018, when Ankara concluded its Operation Olive Branch. Russia’s pressure prevented Turkey from taking over that region. In that instance, Russia acted in the interests of al-Assad’s government and proceeded from the premise that Tell Rifaat had to be a “buffer” or a “safety net” of sorts for Aleppo, separating it from the Operation Olive Branch area. Otherwise, the threat to Aleppo would have remained since the Syrian opposition forces backed by Turkey could undertake a quick offensive against the city (if the situation escalated) at any time, and it would be difficult to repel it.

Subsequently, however, Ankara believed Tell Rifaat to become the main base of the Afrin Liberation Forces affiliated with the SDF; this group had carried out multiple terror attacks in Afrin and other areas of North Aleppo that are under Turkey’s protection. Consequently, Tell Rifaat was repeatedly named as the target of a possible Turkish military offensive, but never became such even when 2019 Operation Source of Peace was conducted in Syria’s northeast. Its crucial role as Aleppo’s “safety net” and Turkish and Syrian opposition forces entering it may result in a direct conflict between Ankara and Damascus.

Another SDF enclave on the Manbij salient, with the city of Manbij as its center, is also connected with Tell Rifaat and, like Tell Rifaat, it is separated from the rest of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria by the river Euphrates and it is cut off from Tell Rifaat by the Operation Euphrates Shield area and by Syrian government forces.

Manbij neither was a target of attacks during Operation Source of Peace. Another factor is at work here, no less crucial than the one applied to Tell Rifaat. The strategically important M4 route runs through Manbij—it connects Aleppo with East Syria up to Iraq. If Manbij transitions under the control of Turkey and the SNA, communications along M4 may be cut off at any moment. Safe area of Operation Source of Peace was envisaged in such a way as to not cross this route.

In the first scenario—if an operation is conducted in the direction of Tell Rifaat and Manbij—Turkey’s advantage may lie in the fact that the U.S. had never taken these areas under its security umbrella. If Ankara advances against them, it will hardly exacerbate its relations with Washington, which means Ankara may not need to coordinate its operation with the U.S. That, however, will require that Turkey convince Russia to change its mind, which is not a simple task since Manbij and Tell Rifaat transitioning under Turkey’s “protectorate” may be more sensitive for both Damascus and Moscow than larger territories in Syria’s northeast being under the “American umbrella.”

The second scenario — extending the “Source of Peace” safe area eastward (up to the border with Iraq) and westward (up to the Euphrates). Essentially, this scenario may be dubbed Operation Source of Peace 2.0, meaning it continues the underlying scenario of Operation Source of Peace that had never been implemented in full. The main obstacle here is the stance of Washington that may openly support its SDF allies. While U.S. air strikes against Turkish troops can be ruled out, the SNA attacking pro-Turkish units is quite likely. Certainly, Turkey and its Syrian allies may be able to conclude what they have started even given the U.S. direct counteraction, but it could topple U.S.–Turkey relations to their post-war nadir. In the current situation, Ankara is unlikely to strike some kind of arrangements with the U.S. Therefore, if Turkey decides to follow this course, it’s going to play an all-or-nothing game.

We cannot rule out the possibility of this scenario having the most pernicious effect on the Euro-Atlantic solidarity. Moscow still has certain leverage to manage this situation, since Syria’s SDF-controlled northeast is essentially split into two areas of responsibility, the Russian-Syrian one in the west and American in the east. Americans still apparently hold the advantage in both areas as they control the air space over both. Washington most likely takes into account possible Moscow–Ankara arrangements concerning a Turkish operation intended to expand the Source of Peace area. Consequently, the U.S., as stated above, began rebuilding the bases they left in 2019 with a view to prevent an advance of Turkish units and their allied Syrian opposition units should Russian troops withdraw from the area.

The third scenario is the most radical one. It envisions Turkey and its allies advancing toward Tell Rifaat and Manbij as well as eastward and westward from the Operation Source of Peace area. The goal is to finally establish a safe zone stretching from Idlib to Iraq’s border. In this case, Ankara will have to overcome the resistance of both Washington and Moscow, and it will make it harder to use their differences to Turkey’s advantage, but still, the chances of pulling this operation off are now higher than ever.

The fourth scenario is more or less in line with the first two. For instance, Turkish troops attack Ayn-al-Arab (Kobani) to link together the areas of Operation Source of Peace and Operation Euphrates Shield; or else, there is a simultaneous advance at Ayn-al-Arab and Manbij (and/or Tell Rifaat), an option that cannot be ruled out. In the very least, this scenario will not affect the U.S. safe zone in Syria’s northeast and it will be implemented in the areas where Washington’s direct counteraction is hardly to be expected.

A game in the Ankara–Washington–Moscow triangle

Ankara can count on some trump cards in its game with Moscow. Maybe, as in 2018 and in 2019, it will succeed in obtaining Moscow’s favorably neutral stance. It may use such “aces up its sleeve” as re-opening an air corridor through Turkey into Syria that Turkey closed on April 23; or else, it may block NATO warships’ passage into the Black Sea no matter how hard NATO tries to push Turkey into revoking its prohibition under various pretexts. Finally, another trump card may be Turkey’s refusal to accede to anti-Russian sanctions.

In the current situation, a conflict with Turkey may turn out to be too costly for Moscow, while direct opposition to Turkey’s plans (primarily if Damascus insists on it) may result in Ankara changing its approaches to the detriment of Russia. However, given Russia’s engagement in hostilities in Ukraine, Turkey can achieve its goals in Syria despite obstacles from Moscow and Damascus. Turkey’s military potential allows for that, especially if it decides to play an all-or-nothing game with the U.S.

Should Turkey launch a new military operation, the principal task for Russia— now busy with the Ukrainian crisis—appears to be to withdraw from the game, having obtained direct preferences both connected with its military operation in Ukraine and in Syria. It would be expedient for Russia to draw its “red lines” for Turkey. First, it is unblocking M4 route. Any Turkish military action should not cross this “red line” (M4 route), endangering communications via this route, since it is strategically important for Damascus as it essentially integrates Syria along the west-east axis.

Turkey will most likely use its grievances over non-compliance with the 2019 Sochi memorandum (and with the Pence-Erdogan deal) as the cause for a new operation. The same holds true for there being no progress in withdrawing SDF-affiliated People’s Defense Units (YPG) from Tell Rifaat, Manbij, and the 30-kilometer area along the Turkey–Syria border in the country’s northeast. Moscow should parry such Turkish claims with a demand concerning implementation of the provisions of the additional protocol to the Memorandum on Idlib that stipulates unblocking M4 route through the de-escalation area and establishing safe zones northward and southward. Turkey avoided complying with these obligations. When I asked Turkish experts on this matter, they pointed out that there remained problems in Russia complying with the 2019 Sochi Memorandum, apparently tying these two problems together.

In case Ankara launches a military operation without complying with the terms on M4 in Idlib, it may cost Russia major reputational losses in the eyes of its Syrian ally, and these losses are to be avoided. The U.S. may also suffer similar losses as it assumes responsibility for supporting the SDF, calling it America’s close ally. After the U.S. has essentially fled Afghanistan, another such case will result in the U.S. Middle Eastern allies totally losing confidence in America as a security guarantor. Washington should not be stripped of its “crown of alliance” with the SDF as it may ultimately prove a “crown of thorns.”

On the other hand, the U.S. is likely to consent to Turkey conducting such an operation in the end. First, it will not endanger the existence of the SDF, it will only expand the safe strip along the border; second, such a sacrifice on the part of Washington may prompt Turkey to unblock Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO.