Halal as the Staff of Life: “New” Growth Areas in Russian–Indonesian Trade Ties

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

Ph.D. in Political Science, Deputy Director of the Centre for Comprehensive European and International Studies (CCEIS), HSE University

Russian exports have been making rapid inroads into the Indonesian markets since the start of the special military operation, adapting to local regulations and specifics. Under favorable conditions, Russia could secure a more systematic presence in certain niches, particularly in agriculture and energy. This could add a new depth to bilateral relations and become their hallmark for years to come, especially amid the uncertain outlook for Russian arms exports to Indonesia and the dynamics within BRICS.

Despite all the imbalances and complexities, trade and economic relations between Indonesia and Russia are in their honeymoon phase after the beginning of the special military operation. Russian exports have seen record growth, an FTA with the EAEU is on the horizon, and efforts are underway to develop the financial infrastructure for mutual trade. However, it is important not to be misinformed by all these positive signals or set expectations too high. Russia’s goal for the coming years is to increase Indonesia’s reliance on certain Russian exports, such as fertilizers, wheat and coal briquettes. The more ambitious and long-term goal is to scale these achievements across entire industries—agriculture, energy and pharmaceuticals.

Russian exports have been making rapid inroads into the Indonesian markets since the start of the special military operation, adapting to local regulations and specifics. Under favorable conditions, Russia could secure a more systematic presence in certain niches, particularly in agriculture and energy. This could add a new depth to bilateral relations and become their hallmark for years to come, especially amid the uncertain outlook for Russian arms exports to Indonesia and the dynamics within BRICS.

Since the beginning of the special military operation, discussions on Russian–Indonesian relations have largely centered around three main topics. The first concerns the overall prospects for developing diplomatic dialogue, given the sanctions pressure on Russia and Indonesia’s peace plan for resolving the Ukraine crisis. The second is about the future of military-technical cooperation after Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s former Defense Minister, took office as president, especially in relation to the drawn-out plans to supply Russian Su-35 fighter jets. The third is about the outlook for a free trade agreement (FTA) between the EAEU and Indonesia, which experts and officials have been eagerly awaiting.

Since 2023, another meaningful theme has emerged: closer integration of Indonesia into BRICS and—after the country’s official accession—a comprehensive assessment of the prospects for Russian–Indonesian cooperation within the bloc.

As can be observed, issues of bilateral trade and economic engagement between Russia and Indonesia have often been overshadowed by the larger military-political and global agenda. The first naval military exercises in the history of Russian–Indonesian relations, conducted in 2024, played a major role in this context. They sparked a new round of expert discussions in both nations on elevating relations to a fundamentally new strategic level and exploring the potential to transform these joint drills into broader military-technical cooperation.

It is no secret that security has traditionally taken precedence over trade and economic cooperation, and Russian–Indonesian relations are no exception in this regard. However, the dialogue on military-technical cooperation, especially the deliveries of Russian arms to Indonesia, is a problematic and in many ways toxic topic. That said, the real prospects for developing military-technical cooperation, as well as bilateral relations in general, are often overestimated, stigmatized or simplified to a primitive equation—Indonesia has proposed a peace plan for Ukraine, joined BRICS, conducted joint military exercises and elected “pro-Russian” President Prabowo—hence, purchases of Russian military hardware and open support for Moscow on Ukraine issue are only a matter of time. Such conclusions are meaningless and ignore the realities of, at the very least, Indonesia’s multi-vector and proactive policy under Prawobo, which he has been vigorously promoting. One of the dimensions of this policy, albeit not so widely covered in global media and expert discussions, is mutual trade, which is evolving in intriguing ways.

Beyond just figures

The special military operation and its impact have spurred Russian–Indonesian trade, which amounted to $3.3 billion in 2023, up 22% from pre-crisis 2021. At first glance, these are unremarkable figures, which contradict Russia’s declared pivot to the East and the rapid reorientation of commodity flows to countries of the Global South after 2022. One could speculate a lot about the reasons behind this—sanctions, geographical remoteness and the resulting logistical constraints, insufficient market presence in both countries, difficulties in business communication, and more. These are all symptoms; the core issue is the goal-setting mechanism. Like the entire Southeast Asia, Indonesia has never been a priority region for Russia and will hardly become one anytime soon. Thus, the issues discussed above trace back to Russia’s initial strategic planning. Jakarta and other ASEAN partners play an important but ancillary role in the Russian foreign trade strategy.

First, this refers to the partial diversification of Russian exports in certain product categories, including as a way to reduce the growing dependence of the national economy on other Asian markets, particularly those of China and India.

Second, this function implies an even more targeted substitution of imports that were lost after Western trade routes closed—primarily high-tech goods such as industrial products and electronics.

Russia, in turn, is not among Indonesia’s priority trade and economic partners either, with the exception of certain product categories. In terms of its economic presence in Southeast Asia, Russia is a textbook example of a middle power, with a typical set of advantages and limitations inherent to such countries, and ranks alongside countries like Canada, Australia and New Zealand. This is why Russian–Indonesian trade ties, by definition, cannot aspire to anything beyond niche cooperation, and the imminent signing of an FTA involving the EAEU will not remedy this situation.

However, this should not be perceived as a setback or a weakness in bilateral relations. There is no need to chase impressive trade turnover figures, which do not always reflect the real dynamics of mutual trade. A much more pragmatic and rewarding approach is to strengthen Russia’s targeted presence in specific sectors of the Indonesian economy. This requires a systematic effort so that Moscow could secure certain niches for the long term, independent of the sanctions situation. There are several trade areas where Russia is already a strategically important player for Jakarta or has the potential to play a more significant role. Given the trade surplus (73% in favor of Russia) and Moscow’s interests, the following section will focus on the most promising categories of Russian exports to Indonesia and the barriers to further growth. In all of these areas, except for asbestos, Russia has managed to increase its share in the Indonesian market since the start of the special military operation.

Mineral resources

In terms of product nomenclature, Russia’s main strategic interest in trade with Indonesia boils down to increasing supplies of mineral resources, specifically coal briquettes—a crucial commodity that accounted for 34% of Russia’s total exports to Indonesia and valued at $828 million in 2023. Notably, these supplies have seen explosive growth—rising nearly 4.5 times compared to 2021—which allowed Russia to expand its share in Indonesia’s total imports of this product to 23.6% in 2022–2023, up from 8.2% in 2021 (see Table 1). This puts Russia second only to Australia, which accounts for nearly half of Indonesia’s coal briquette imports. Consequently, competition with other foreign suppliers poses little risk to Russia’s standing in the Indonesian market.

The key challenge lies in Indonesia’s ambition to cut its carbon footprint in the national economy and transition to cleaner energy sources, including liquefied natural gas (LNG). However, this move has yet to materialize, as coal briquette imports remain high in the past three years, domestic consumption is rising, and coal production hit a new high at 831 million tons in 2024. At the same time, coal accounted for 61.8% of Indonesia’s power generation in 2023—the second-highest share in Southeast Asia after the Philippines. Furthermore, Indonesia’s shift away from coal imports and production could potentially open a window of opportunity for Russian LNG exporters.

Table 1. Russia’s share in Indonesia’s total imports of selected products based on the 4-digit HS code, 2018–2023, %

| Commodity | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizers | 15,6 | 16,9 | 15,7 | 14,8 | 22,7 |

| Wheat and meslin | 11,3 | 4,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 7,3 |

| Millet | 0,2 | 0 | 0,2 | 10,1 | 28,5 |

| Frozen fish | 1,5 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 15,6 |

| Coal briquettes | 14,4 | 16,2 | 17,6 | 8,2 | 23,6 |

| Semi-finished products of iron or non-alloy steel | 26,2 | 17,1 | 16,7 | 14,8 | 18,8 |

| Asbestos | 78 | 90,8 | 98,6 | 96,7 | 77,2 |

Source: compiled by the author with data from Trade Map

Fertilizers

The export dynamics of fertilizers, Indonesia’s second-largest import category, have been mixed. On the one hand, after the start of the special military operation, Russia managed for the first time to overtake China and Canada to become the top supplier of this product to Indonesia. On the other hand, the value of Russian fertilizer exports dropped sharply from $811 million in 2022 to $481 million in 2023. However, in this case, it is not the absolute figures that matter, but Russia’s overall share in the Indonesian market, which increased to 22.7% (see Table 1).

The decline in fertilizer exports to Indonesia in nominal terms follows a broader trend affecting all of Jakarta’s key partners, especially Canada, whose exports fell fourfold. This is directly related to Indonesia’s import substitution policy. The country seeks to boost its agricultural productivity by building fertilizer plants and promoting a government program to subsidize farmers, thereby strengthening food security—a key priority for President Prabowo Subianto. In many ways, this policy is the main risk for Russia in the coming years, as Indonesia plans to achieve partial self-sufficiency by 2027, which primarily means reducing its dependence on imports from Russia, China and Canada.

Food products

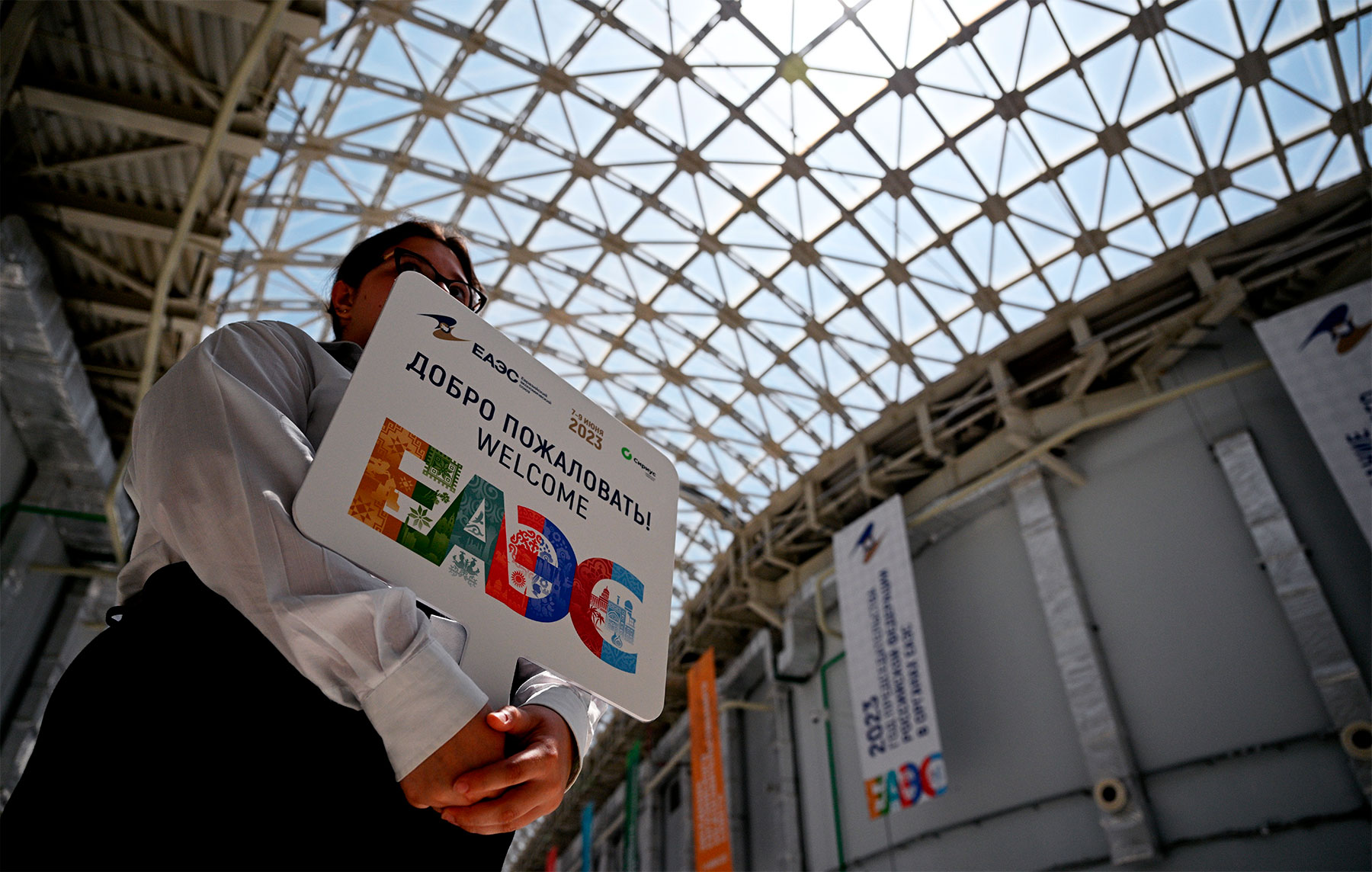

Proactive vs Reactive: Interim Results of the EAEU's Foreign Economic Policy

One of the most promising categories of Russian exports is agricultural products, with supplies increasing sixfold in 2023 compared to 2022. The main driver of growth was the resumption of wheat and meslin deliveries in May 2023, which totaled $275 million for the year—up from $825,000 over the previous two years combined. As a result, Russia climbed to fourth place among the top five suppliers with a market share of over 7% in 2022–2023 (see Table 1). Looking ahead, Russia has the potential to overtake Bulgaria, which currently ranks third with only a slim lead.

In 2023, Russia also remained Indonesia’s second-largest supplier of millet, behind the U.S., with exports worth $10.7 million and a 28.5% share in Indonesia’s total imports of this product (see Table 1). With Indonesia’s population and domestic consumption on the rise (the country ranks as the world’s third-largest importer of wheat and meslin after China and Egypt), Russia has a chance to strengthen its foothold in the grain market. Furthermore, Indonesia has chronic difficulties in growing its own agricultural crops, and its import substitution policy is mainly focused on fertilizers.

Frozen fish

In addition to wheat and meslin, Russia can expand its footprint in the Indonesian frozen fish market, where it has already established a solid economic foundation. Among all the examined export items, this product stands out for its continuous growth in Russia’s share in total Indonesian imports, from 1.5% in 2018 to 15.6% in 2022–2023 (see Table 1). Since 2021, Russia has secured a position as Indonesia’s second-largest supplier of frozen fish, next only to China, which has controlled over 33% of the market for the past two years.

Meanwhile, bureaucratic barriers hinder the expansion of Russia’s presence in the food market.

First, Law No. 33/2014, on Halal Product Assurance, mandates certification for a long list of products under halal standards. This requirement applies to the full business cycle of export-import operations, from storage and distribution to marketing. The Halal Product Assurance Agency (Badan Penyelenggara Produk Halal), under the Indonesian Ministry of Religious Affairs, oversees the entire process. The law directly affects the interests of Russian companies, as it extends to a wide range of promising Russian exports, including agricultural and chemical products (fertilizers).

Second, there are problems with the lack of transparency in import licensing for agricultural products and compliance with phytosanitary quality requirements for imported goods, as well as occasional delays in obtaining import certificates for Indonesian companies, especially at the beginning of each calendar year.

Third, high customs duties hinder Russia’s efforts to expand its market presence. The tariff rate applied to Russian frozen fish exports to Indonesia stands at 7.5%—the same as for Seychelles, a major supplier of this product to Indonesia. Meanwhile, Russia’s competitors benefit from significantly lower import duties: 5.36% for Chile, 1.76% for Norway and zero for China and Australia due to their FTAs with ASEAN. This barrier could be removed or mitigated with the signing and further ratification of the EAEU–Indonesia FTA, which is likely to include a provision on fish exports. Otherwise, Russia, under the framework of the Eurasian Economic Commission, should insist during negotiations with its Indonesian counterparts on expanding a preferential trade regime for EAEU member states regarding this product category.

Finally, the lack of an electronic veterinary certification system, particularly the integration of state databases for veterinary control, is another obstacle to the export of fishery products. However, this issue is being addressed at the official level, as evidenced by a statement from Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Patrushev, who previously served as agriculture minister. A number of these issues, including the development of the halal industry, will be discussed during industry sessions at the Russia–Indonesia Business Forum. It will be held on April 14–15, 2025, in Jakarta, on the sidelines of the Russian–Indonesian Joint Commission on Trade, Economic, and Technical Cooperation meeting, in partnership with the Roscongress Foundation and the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KADIN).

Iron and steel

The reorientation of Russian export flows after the start of the special military operation allowed Russia to strengthen its niche presence in the Indonesian steel market in 2022. In particular, iron and steel exports grew by nearly 1.5 times over the year, from $447 million in 2021 to $585 million in 2022. However, in 2023, total export volumes declined significantly to $409 million—returning to pre-pandemic levels recorded in 2019. This sharp drop was primarily caused by the near halt in supplies of products obtained by direct reduction of iron ore, which fell from $106 million in 2022 to just $19 million in 2023. Furthermore, in 2024, there was a decrease in the export of the largest product category within this group—semi-finished products of iron or non-alloy steel—from $461 million in 2022 to $390 million in 2023. This puts Russia in second place among the largest exporters to Indonesia, next only to Oman. At the same time, from 2022 onward, Russia has increased its share in the Indonesian market for semi-finished products from 14.8% in 2021 to 18.8% in 2022–2023 (see Table 1).

For Indonesia, the iron and steel market is one of the most sensitive, as local producers suffer significant losses due to the strong presence of foreign players. In order to stimulate domestic business, the country’s leadership regularly introduces various protectionist measures, which directly impact Russia’s interests. In particular, according to a decree issued by the Indonesian Ministry of Finance, from 2019 to 2030, the anti-dumping duties on hot-rolled flat products in coils apply to Russia as follows: 5.58% for PJSC Severstal, 8.96% for PJSC NLMK, 20% for PJSC MMK and 20% for other Russian companies. This has effectively shut Russian businesses out of the hot-rolled coil market, as reflected by years of zero exports of this product to Indonesia. Similar restrictions were introduced in 2024 against China, including Taiwan, and South Korea, covering all types of tin-coated flat-rolled products of carbon and alloy steel.

In addition, strict regulations on the import of metallurgical products were in place until May 2024. Specifically, Indonesian companies were required to obtain a special permission from the Ministry of Industry in the form of an import license (PI), a recommendation or technical consideration (Pertek) and an import technical verification and tracing (LS) to import iron, non-alloy steel and related products. Following amendments to previous documents and the introduction of the revised “Ministry of Trade Regulation No. 8” in May 2024, import licenses are no longer required. However, other bureaucratic regulations remain in place. In addition, the exemption from prohibitions and restrictions on imports of iron and steel only applies to commercial activities of up to $1,500 per shipment. In practice, the complex customs declaration system complicates communication between foreign exporters and their Indonesian counterparts, increases costs and considerably prolongs transaction approval timelines.

Asbestos

Can Southeast Asia Avoid Hierarchy?

Among Russian exports to Indonesia, asbestos stands out. In some years (2019–2021), Russia held a near-monopoly, accounting for over 90% of all Indonesian asbestos imports (see Table 1). This was largely driven by the country’s low domestic demand and the extremely limited supply from foreign partners. Apart from Russia, only three countries, Brazil, China and Kazakhstan, export asbestos to Indonesia. In 2022–2023, Russia’s share sank to 77.2% due to three factors: a drop in Russian exports, a more than twofold increase in Chinese exports and Brazil’s entry into the Indonesian market. Nevertheless, given the limited supply, there are no objective reasons for Russia to lose its competitive edge here.

Pharmaceuticals

Another area of trade and economic cooperation that is currently underrepresented in absolute figures but has growth potential is the supply of pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. One success story is the entry of the Russian company Polysan into the Indonesian market in 2023 with its Reamberin drug, which has anti-hypoxic and antioxidant properties. The expansion of cooperation in the pharmaceutical industry was also actively discussed at a high level during the meeting of the Russian–Indonesian Working Group on Trade, Industry and Investment at the 15th International Economic Forum “Russia–Islamic World: KazanForum” in May 2024. In particular, Indonesian delegates expressed their readiness to facilitate access of Russian pharmaceuticals to the local market.

To a large extent, it is administrative barriers that prevent both countries from working more systematically in this area. For example, under Ministry of Health Regulation No. 1010 of 2008, any foreign pharmaceutical company must either localize its production of medicines in Indonesia or form a partnership with a local manufacturer. The latter requirement allows an Indonesian-registered national company to obtain regulatory approvals on behalf of its foreign partner to produce and sell products in the country.

Furthermore, in January 2023, the Indonesian government issued Decree No. 6, mandating that medicines, biological products and medical devices sold in the country, as well as their production methods (including related materials, processing, storage and packaging), must obtain halal certification. In this context, it appears most reasonable to explore ways to ease market entry for Russian companies.

However, boosting Russian exports to Indonesia, even with the implementation of an FTA with the EAEU, will be incomplete without strengthening the business and financial architecture. There are several shortcomings and limitations in this area.

First, institutional ties between the countries in business and finance are underdeveloped—there are no joint banks and Russian banking institutions have no branches in Indonesia. The Russian Export Center (REC) planned to establish a representative office in Jakarta in 2024, but no official announcements have confirmed its opening. The missing address and map marker on REC’s official website, unlike for other countries, strongly suggests that the office in Indonesia is not yet operational.

Second, due to concerns about secondary sanctions, Indonesian banks are cautious about building payment and settlement cooperation with Russia, particularly when it comes to connecting to the Russian alternative to SWIFT—the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS). The Central Bank of Russia does not provide a detailed country-by-country breakdown for the number of banks connected to the system. However, it can be assumed that even if some Indonesian financial institutions are integrated with the SPFS, there are only a few of them.

Third, there is no publicly available data on mutual trade in national currencies. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that most transactions are conducted in U.S. dollars. This conclusion is indirectly supported by Bank Indonesia’s statistics, which show that over 90% of the country’s foreign trade is settled in dollars. In addition, Indonesia has not yet integrated Russia’s Mir payment system, which, among other things, is informed by financial concerns and sanctions compliance requirements.

Nevertheless, developing financial and settlement integration is one of the promising areas in the evolution of Russian–Indonesian relations, which is gradually gaining support at the official level in both countries. For example, back in 2022, at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Indonesia to Russia Jose Tavares stated that the countries were negotiating the launch of settlements in national currencies. In a January 2025 interview with the Jakarta Globe, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Russia to Indonesia Sergei Tolchenov confirmed that discussions on this matter were actively underway with Jakarta, though he refrained from speculating on a timeline for implementation. Meanwhile, the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism is looking into ways to accept Russian Mir cards as a payment method for the tourist levy in Bali, considering the high number of tourist arrivals from Russia to the island.

Indonesia takes the issue of de-dollarization seriously, promoting the rupiah and the transition to mutual trade in national currencies with partners as one of the priorities to ensure financial sovereignty and economic resilience. While the escalation of the Ukraine crisis in 2022 accelerated this process, Indonesia had been laying the groundwork long before the special military operation. In particular, Bank Indonesia has been promoting the Local Currency Transaction (LCT) mechanism in bilateral trade transactions with partner countries since 2017. As of 2025, Indonesia has signed memorandums of understanding on using the LCT mechanism with the central banks of Japan, South Korea, India, the UAE, China, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. This approach is beginning to bear fruit: according to official data, trade in national currencies reached $6.3 billion in 2023, with further growth expected.

To ensure cross-border financial interconnectivity and facilitate the broader adoption of the LCT mechanism, Bank Indonesia has prepared the Indonesia Payment System Blueprint 2030 (BSPI), which serves as a roadmap for improving cross-border payment systems. The key tool for promoting LCT and implementing this roadmap is the introduction of the Quick Response Code Indonesia Standard (QRIS), which is essentially a QR code-based payment system. This system is already in use for financial transactions in Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore, and Bank Indonesia aims to expand it to non-ASEAN partners such as South Korea, the UAE, Japan and India.

Indonesia’s proactive efforts to put in place an alternative financial architecture opens avenues for joint cooperation with Russia and, in the longer term, with the EAEU. This could involve signing a memorandum of understanding between the countries’ central banks to use national currencies in settling trade through the LCT mechanism and/or integrating Russia into QRIS. A more complex approach would be to synchronize national payment systems and enable QR code-based cross-border transfers in national currencies, bypassing the U.S. dollar in conversions.

Despite all the imbalances and complexities, trade and economic relations between Indonesia and Russia are in their honeymoon phase after the beginning of the special military operation. Russian exports have seen record growth, an FTA with the EAEU is on the horizon, and efforts are underway to develop the financial infrastructure for mutual trade. However, it is important not to be misinformed by all these positive signals or set expectations too high. Russia’s goal for the coming years is to increase Indonesia’s reliance on certain Russian exports, such as fertilizers, wheat and coal briquettes. The more ambitious and long-term goal is to scale these achievements across entire industries—agriculture, energy and pharmaceuticals.

(votes: 2, rating: 5) |

(2 votes) |

Working Paper No. 83 / 2024

Prabowo Subianto at Shangri-La Dialogue Forum: Trilogy 2022–2024Indonesia continues to pursue an independent international policy despite Western pressure

Can Southeast Asia Avoid Hierarchy?China seeks to give more than it takes