In recent years, the relationship between Moscow and Brussels resembled a balancing act based on asymmetrical weaknesses rather than strengths. Russia’s Achilles’ heel was its stagnating and archaic resource-based economic model, which caused Russia’s share in the global economy to steadily decline, and consequently its significance as an economic partner of the European Union.

For the past five or six years, Russia and the EU have been waiting for a black swan event that would compel their opponent to acknowledge the error of their ways, to rethink their attitudes, and to make at least symbolic concessions. During that time frame, numerous black swans in global politics flew by without disrupting the new normal for EU-Russia relations that had emerged in 2014, and which proved surprisingly stable and quite acceptable to both sides ever since.

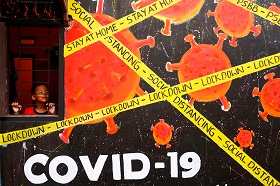

But then along came the mother of all black swan events: the coronavirus pandemic. It’s already clear that the EU and Russia will be among its prime victims. The EU states have found themselves at the epicenter of the pandemic, while Russia must simultaneously deal with a major threat to public health and its long-running economic model.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel openly acknowledges that the EU is facing “the biggest challenge since its foundation.” Russian President Vladimir Putin eschews such admissions, but he hasn’t had to fight such a complex battle on two fronts since coming to power over twenty years ago.

The end of the current public health and economic crisis is nowhere in sight, but it’s already clear that both Moscow and Brussels will come out of it weakened, both in absolute terms and relative to other global political actors. Ostensibly, this sad reality should prod both sides toward conciliatory gestures. But nothing at this time suggests that a relationship founded on a balancing act of weaknesses is likely to change substantially in the context of the pandemic.

Many experts predict that the coronavirus pandemic will sharply accelerate the ongoing restructuring of international relations, which may eventually lead to U.S.-China bipolarity. Neither Russia nor the EU is interested in the creation of a rigid global bipolar system that would hamstring freedom of maneuver on the world stage for both sides. Maintaining and developing cooperation between Moscow and Brussels could be one mechanism for inhibiting that negative trend.

In recent years, the relationship between Moscow and Brussels resembled a balancing act based on asymmetrical weaknesses rather than strengths. Russia’s Achilles’ heel was its stagnating and archaic resource-based economic model, which caused Russia’s share in the global economy to steadily decline, and consequently its significance as an economic partner of the European Union.

The EU’s weaknesses mostly stemmed from the irreversible decline of traditional party and political systems in its leading member states that had prevailed throughout the post-war era and, consequently, their inability to provide the political leadership that the EU so badly needed. This led to a lack of European unity, which manifested itself in the EU states’ responses to many issues, from the migration crisis and the rise of right-wing populism to their halting attempts at unity in approaching their difficult neighbor to the east in the wake of the Ukraine conflict.

For the past five or six years, Russia and the EU have been waiting for a black swan event that would compel their opponent to acknowledge the error of their ways, to rethink their attitudes, and to make at least symbolic concessions. During that time frame, numerous black swans in global politics flew by without disrupting the new normal for EU-Russia relations that had emerged in 2014, and which proved surprisingly stable and quite acceptable to both sides ever since.

But then along came the mother of all black swan events: the coronavirus pandemic. It’s already clear that the EU and Russia will be among its prime victims. The EU states have found themselves at the epicenter of the pandemic, while Russia must simultaneously deal with a major threat to public health and its long-running economic model.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel openly acknowledges that the EU is facing “the biggest challenge since its foundation.” Russian President Vladimir Putin eschews such admissions, but he hasn’t had to fight such a complex battle on two fronts since coming to power over twenty years ago.

The end of the current public health and economic crisis is nowhere in sight, but it’s already clear that both Moscow and Brussels will come out of it weakened, both in absolute terms and relative to other global political actors. Ostensibly, this sad reality should prod both sides toward conciliatory gestures. But nothing at this time suggests that a relationship founded on a balancing act of weaknesses is likely to change substantially in the context of the pandemic.

Brussels, it seems, is still not prepared to have a serious discussion of EU strategy toward Moscow, even internally. Nor does the Kremlin seem to have anything new to offer the EU. There have been no radical breakthroughs nor even any major positive developments in the implementation of the Minsk agreements on ending the conflict in eastern Ukraine. The EU is reluctant to consider any relaxation of sanctions against Moscow amid the pandemic, although internal divisions widened somewhat in the wake of French President Emmanuel Macron’s outreach to Russia earlier this year. On the contrary, the advent of the coronavirus has only exacerbated the fierce information war between Russia and the West.

In the military strategic sphere, no joint efforts were made to absorb the shock of the U.S. withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. NATO is unable to reach internal consensus about engaging in substantive dialogue with Russian military officials, even as chances for the extension of the New START Treaty grow increasingly slim.

Earlier this year, there was hope that a serious conversation on European security might take place in Moscow during the seventy-fifth anniversary of Victory Day. But those hopes were dashed when commemorative events were postponed because of the pandemic.

Additional economic problems between Russia and the EU are looming. The collapse of oil prices has demolished the core of Russian exports to Europe, while the decline in real incomes combined with the ruble’s devaluation has done the same to European exports to Russia. Some European leaders such as Macron insist that Europe needs to advocate for a rethink of Moscow’s budding partnership with China. Yet, if anything, the current crisis appears to be pushing Moscow and Beijing closer together, especially in the energy and economic spheres. In addition, the Trump administration is reportedly threatening another wave of U.S. sanctions against the controversial Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, a move which would deepen divisions inside the EU and between Washington and Berlin.

Have new opportunities for EU-Russian cooperation appeared since the start of the epidemic? Russia could use the model of its cooperation with Italy to help other EU members, but not everyone in Europe considers that model effective. Moscow and Brussels could coordinate their anti-pandemic programs in neighboring regions — from Central Asia and the Western Balkans to the Middle East and North Africa — but both sides have very limited capabilities for such work under the current conditions.

Then there is the traditional agenda, which includes diverse subjects such as maintaining EU-Eurasian Economic Union dialogue, strengthening the OSCE, developing 5G technology, trying to preserve the Iranian nuclear deal, and cooperating on environmental issues. A fundamental reset of bilateral relations within this framework, however, seems unlikely.

Yet even these relatively modest opportunities shouldn’t be ignored. Many experts predict that the coronavirus pandemic will sharply accelerate the ongoing restructuring of international relations, which may eventually lead to U.S.-China bipolarity. Neither Russia nor the EU is interested in the creation of a rigid global bipolar system that would hamstring freedom of maneuver on the world stage for both sides. Maintaining and developing cooperation between Moscow and Brussels could be one mechanism for inhibiting that negative trend.

This article is part of the Russia-EU: Promoting Informed Dialogue project supported by the EU Delegation to Russia. Andrey Kortunov is one of the EU-Russia Expert Network on Foreign Policy (EUREN) core group members.”

First published in the Carnegie Moscow Center.