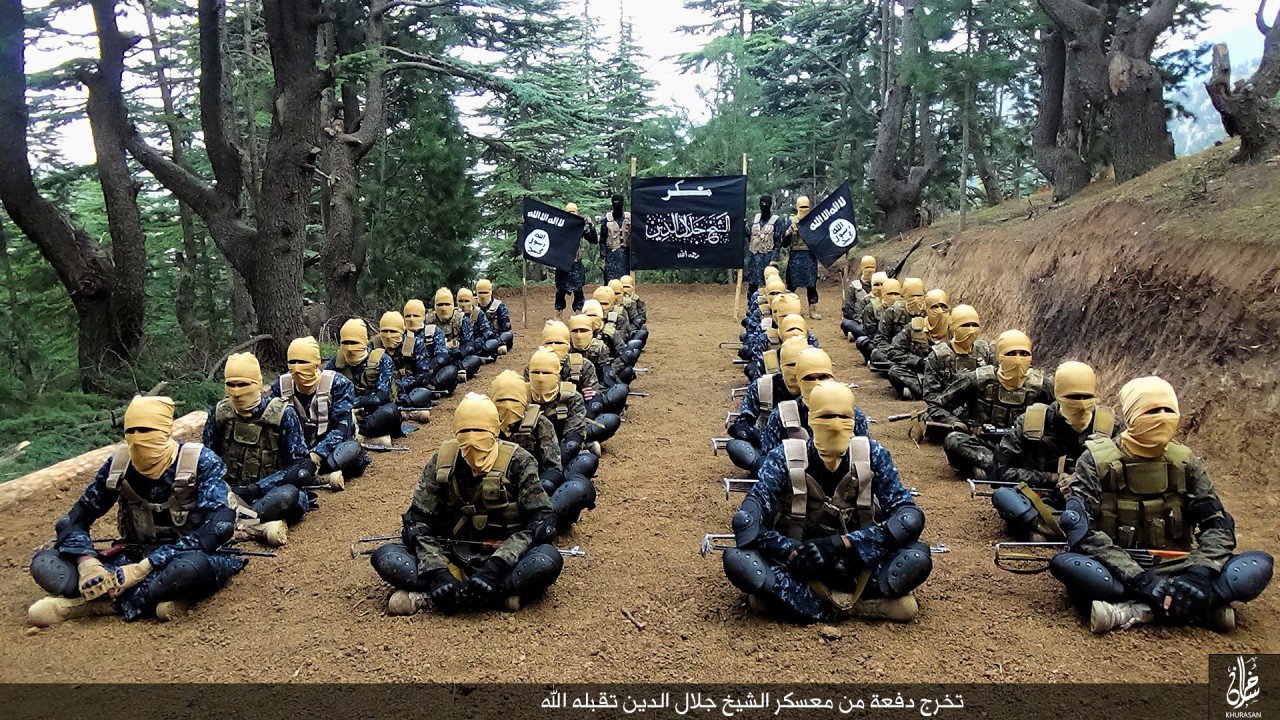

The Islamic State in Afghanistan: a Real Threat to the Region?

Afghan police walk past Islamic State militant

flags on a wall, after an operation in the Kot

district of Jalalabad province east of Kabul,

Afghanistan

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Senior Lecturer at the Department of Social Sciences, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Research Fellow at the Center of Arab and Islamic Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

In January 2015, representatives of the largest for now Islamic regional military-political union in South and Central Asia and the main ally of al-Qaeda in the region, namely the Taliban movement, took their long-awaited oath and pledged loyalty to the Islamic State. A few months of self-proclaimed Caliph’s emissaries’ hard work and negotiations with the Taliban leaders were crowned with success and creation of a new IS stronghold. What are the motives, tools and conditions of IS involvement in processes on the territory of Afghanistan?

At the turn of 2014-2015, the information networks of the terrorist organization the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant were replete with reports of representatives of various Islamist militant groups and movements in Asia and Africa pledging allegiance to its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and proclaiming the formation of new provinces (wilâyâts) of the “caliphate” outside Iraq and Syria (1; 2). Amidst the fear and admiration caused by the triumphal march of IS supporters in 2014 (the capture of Mosul and Tikrit in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria), the recognitions treading on each other’s heels were intended to show the world that from now on, ISIS represented a force of a global scale, comparable to and even surpassing al-Qaeda which had been excessively demonized in the public and expert space.

In January 2015, representatives of the largest for now Islamic regional military-political union in South and Central Asia and the main ally of al-Qaeda in the region, namely the Taliban movement, took their long-awaited oath (Baja) and pledged loyalty. A few months of self-proclaimed Caliph’s emissaries’ hard work and negotiations with the Taliban leaders were crowned with success and creation of a new IS stronghold. Given the recent history of the Af-Pak region (Afghanistan and Pakistan), and the role played in it by the Taliban, it is difficult to overestimate the implications of such an alliance and the future prospects for the countries of Central and South Asia, as well as for the whole system of regional security. What are the motives, tools and conditions of IS involvement in processes on the territory of Afghanistan? What is the degree of this organization’s involvement in the Afghan internal conflict, and how far does its influence on the situation extend?

The main value of the Khorasan Shura for the central leadership of ISIS resided in its mobilizational resource,s namely, the ability to attract and arm a large number of experienced battle-tested soldiers.

The Province of Khorasan: what is it, and how does it work?

The Province of Khorasan (Wilâyat Khurâsân) [1] was proclaimed on January 26, 2015. A year and a half has passed since that time, but the Wilayat still remains a rather virtual (1; 2) phenomenon. The key reason for this has been the lopsided propagandistic nature of actions to establish and maintain it: it was formulated and launched into circulation mainly by the ISIS “central” propaganda apparatus, rather than the local branch. The homogeneous province of Khorasan reflects the perception in Raqqa and Mosul of ISIS presence in the neighboring region with a view of solving the problems in Syria and Iraq, but this perspective takes no account of either local features, or the splits that exist in local communities. Moreover, the unifying message intrinsic to the idea of a single province of such a geographically vast area has not been fully supported and shared by even those apologists for Islamism in the region, who have pledged their loyalty to the Islamic State.

The main value of the Khorasan Shura for

the central leadership of ISIS resided in its

mobilizational resource,s namely, the ability to

attract and arm a large number of experienced

battle-tested soldiers

Thus, the ideological construct dictated by Raqqa failed to enjoy unconditional support among ISIS forces in the region. Followers of the universalist and utterly simplified ideology of the Islamic State [2] were divided due to the lack of shared linguistic community, a single topical agenda, undisputed platform for communication and coordination of the strategy of joint actions at the local level. Much evidence supports the view that numerous groups scattered over such vast expanses have now much more in common with Mosul and Raqqa, than with temporary headquarters of the ruler (Emir) of Khorasan, or with each other.

In and of itself, Wilayat Khorasan at this stage appeared to be an extensive network of highly inhomogeneous cells, scattered over a large area and therefore largely autonomous, each of which had its own motives and goals for cooperating with the Islamic State. Formal management and coordination activities were carried out by the Council (Shura) in a decentralized manner. Presumably, governing institutions and the headquarters were located in the northwest of Pakistan, where the government power is only formal, while local tribal and other unions are easy to make terms with and welcome anyone who is ready to pay for the presence on their land. Actively making themselves known via acts of terrorism and ongoing sabotage, ISIS structures, however, did not have sufficient forces to capture large areas in Afghanistan or Pakistan. This notwithstanding, their influence and presence were quite apparent in certain Afghan provinces (Nanhargar and Kunar), where the positions of the Taliban weakened under pressure from the government forces on one hand, and internecine warfare within its own camp on the other. For all the claims to the contrary of the Pakistani military [3], who for a long time denied this fact, ISIS recruiting and propagandistic teams launched their activities not only in the northwest of the country, but in its other parts too, taking advantage of the authorities’ inactivity and fragmentation which was helpful for them in the ranks of local Islamists.

The transformation of regional branches of the organization into real functioning and belligerent “troops of the Caliphate” is expected to change the course and the rules of war waged by the Islamic State, making it truly global and universal.

The main value of the Khorasan Shura for the central leadership of ISIS resided in its mobilizational resource,s namely, the ability to attract and arm a large number of experienced battle-tested soldiers (veterans of the Afghan war), who had all the required skills not only to lead a long-term guerrilla war, but to conduct large-scale operations too. They accumulated considerable organizational resources and developed transportation routes through the countries of Central Asia (from Afghanistan) and of the Persian Gulf (from Pakistan) for the fighters’ transit to Iraq and Syria in 2014-2015 [4]. Having adopted the best practices of al-Qaeda and enlisted the services of the latter’s personnel, the IS regional operators focused on creating their own logistics system.

Not being able to compete as equals with the Taliban, the IS structures in the region failed to effectively harness local institutions of the shadow economy, including regional smuggling networks, and accumulate in comparable volumes earnings from the production and transit of drugs, arms and food. This explains the insurmountable financial dependence in the foreseeable future of the Province of Khorasan on the IS stronghold in Iraq and Syria, whose budget became the main (if not the only) source of funds for Khorasan’s functioning as a mobilizational and organization system.

Afghans in Iraq and Syria under the banner of ISIS and its enemies

Until the autumn of 2015 and the beginning of 2016the Islamic State was guided in its efforts to call to arms largely by the necessity and feasibility of consolidating its supporters and resources on the territory of Iraq and Syria that became the main front in the struggle for establishing a “new true” caliphate. IS ideologists and propagandists set the goal of building up the military strength of the organization to the greatest possible extent and of gaining a foothold in the heart of the Arab world. At the cost of weakening its position in secondary directions, which at that time included the “Khorasan front of global jihad,” the IS leadership hoped to receive military superiority in the fight against Iraqi and Syrian government forces due to the influx of experienced military personnel from the Afghan conflict zone. According to various estimates (1; 2), during that time, a few hundred or even thousands of ethnic groups living in the territory of the Central Asian states, Afghanistan, Pakistan (Tajiks, Uzbeks, Pashtuns) arrived (made hijrah) through Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon along with hundreds of recruits from around the world to protect the IS stronghold.

When the active phase of large-scale operations conducted in Syria by the Russian Aerospace Forces and regular Syrian Arab army on the one hand, and in Iraq by the Iraqi pro-government forces and the international coalition on the other hand began to bear fruit and the terrain of attack changed, the tone and motives of IS managers’ call underwent a transformation. The new IS global strategy suggested joining jihad with energetic involvement in activities on the place of residence, rather than making Hijrah, or migration to the land of the caliphate (1; 2). The combat veterans from Iraq and Syria, with real skills and fighting experience, as well as the proper ideological training and the right motivation were to help local communities and activists organize this struggle and improve their methods. This explains the outflow of those who arrived in the Syrian-Iraqi war zone in 2014-2015, including Afghans, to their native countries. The transformation of regional branches of the organization that had been originally created as propaganda and mobilization centers into real functioning and belligerent “troops of the Caliphate” is expected to change the course and the rules of war waged by the Islamic State, making it truly global and universal. There is reason to suppose that the actions of certain IS leaders (neither Syrian, nor Iraqi for the most part) pursue the goal of preparing alternate regions for deployment/retreat in the event of losing the main forces of the organization in Syria and Iraq.

The outflow of fighters taking shape is not only able to fundamentally change the nature and significance of the Province of Khorasan and modify the IS tactics and strategy in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but will certainly have an impact on the position of Afghan troops (Kata’ib) in Iraq and Syria. Because of the language factor, Afghan units were reluctant to co-opt Arabs, unless they had to out of necessity. Due to intensified fighting and increased losses in 2016, they faced the problem of maintaining their efficiency and capability, as they could not any longer rely on reinforcements composed of tribesmen from their homeland.

The IG ideology appears to be neither single, nor even dominant in the ideological space and the political discourse of the Afghans.

It is noteworthy that volunteers from Afghanistan are part of the armed Shiite militia groups, fighting in Syria and Iraq against the Islamic State on the side of the sovereign governments of these countries. According to some reports, not all Afghan “mercenaries,” as they are often called by IS propaganda structures, are Shiites protecting holy Shia sites and people from extermination by Islamic State extremists. Some of them are Sunnis and followers of large Sufi brotherhoods, whose presence and influence historically extends far beyond the Middle East. The threat posed by the activities of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s upholders has brought together representatives of different groups of the Afghan population and motivated them to unite their efforts in the joint struggle outside their own country and Af-Pak region. The observed active participation of Afghan Sunni in the military-political processes in the Middle East – not only under the banner of the international Islamist terrorist movements, but in the camp of their opponents as well – appears to be a new and, in some ways, unique phenomenon that has demonstrated the nature of the Afghan community reaction to the challenge from the Islamic State. Thus, the IG ideology appears to be neither single, nor even dominant in the ideological space and the political discourse of the Afghans. In turn, religious identities existing in South and Central Asia, as well as appealing with them alternative political and religio-political concepts (including fundamentalist ones) that draw on traditional or newly established in the last decade institutions, make a reliable basis for mobilizing the population and limiting the influence of external by nature forces.

During the previous Iraqi wars (1990-1991 and 2003-2004), the unrest in Pakistan (mostly of followers of Sufi brotherhoods), caused by Muslim solidarity and the desire to protect Islamic holy sites in Iraq, did not go beyond protest demonstrations with anti-American and “pro-Saddam” slogans, fundraising and the provision of financial assistance to the Iraqi communities affected by war [5]. As it currently stands, since the Islamic State is perceived as an absolute threat, Afghan religious elites have moved beyond rhetoric and now participate directly in the combat against it in Iraq and Syria.

In recent years, Tehran has acquired a reputation as an implacable and most persistent enemy of IS in the Islamic world.

What are these new conditions? The most important here seems to be a new level of awareness of the Afghan and Pakistani political organizations. They build on religious and political discourse and seek to use it for accumulating mass support. They act in the Af-Pak region, trying not only to offer the people solutions for their local and regional problems, but also claim to be the guides leading the historically isolated local Muslim community into a big modern world. There are at least three groups of actors. First, the radical Islamist network structures, namely al-Qaeda, which appeals to the Sunni majority from the perspective of Islam and Islamic fundamentalism. Second, the political structures originating from South Asian schools of Muslim theologians and Sufi tariqats Deobandi and Barelvi. Deobandi followers fleshed out the Taliban movement in the 1990s both ideologically and spiritually [6], while Barelvi adherents, in turn, have a close relationship with Iraq, which has on its territory sacred for them graves of distinguished opinion leaders and spiritual guides [7]. Third, Shiite political organizations that one way or another are dependent on Iran and come under the religious and political influence of Qom and Tehran.

It should be noted that the new level of mediation by Iran has become an important factor for the increased involvement of Afghans in the fight against the Islamic State in the territory of Syria and Iraq, as well as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Today, the Islamic Republic of Iran enjoys great prestige and has at its disposal an arsenal of tools to project its influence in neighboring regions. In recent years, Tehran has acquired a reputation as an implacable and most persistent enemy of IS in the Islamic world. Paradoxically, the Islamic State propaganda promotes this image too, as it describes the Shiites and the “Safavid state” (as it calls the Islamic Republic of Iran) as its main enemy within the Muslim community (ummah).

“Every little bit helps:” who is fighting on the side of the Islamic State in Afghanistan and Pakistan?

Most of the Taliban warlords who swore allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2014-2015 were members of the Pakistani branch of the Taliban, namely the Taliban Movement of Pakistan (Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, TTP). Nevertheless, the composition of IS supporters in the region is not confined only to Pakistani Pashtuns, who make up a significant part of the TTP members. The death of Mullah Omar and the premature death of his successor Mohammed Mansour in 2016 caused turmoil within the Afghan Taliban at a time of the Islamic State’s rush of success and contributed to the consistent fragmentation of the Taliban as a whole, creating favorable conditions for adopting the IS banner by Taliban’s regional leaders and functionaries. The extreme radical opponents of the political settlement of the Afghan and Pakistani crisis became the Islamic State’s tower of strength. They were joined by those who considered themselves disadvantaged and deprived of any prospects in the new configuration of power and control with the new emir – Maulvi Heybatulle Akhundzade.

However, it is worth noting that the loyalty of the Pashtun leaders has always been rather relative. Even declaring their commitment to the ideals of the Islamic State and loyalty to its political course, they have not broken off relations with the Taliban and some local al-Qaeda actors: they are in no hurry to sever the existing contacts as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi did in Iraq and Syria.

In turn, the Taliban, being separated and fragmented due to the current political leadership crisis and lack of effective management, benefits from IS terrorist activities, its conflict-ridden relationship with the latter notwithstanding.

The units composed of ethnic minorities (Uzbeks, Tajiks, Uighurs), who found themselves in Pakistan in 2003-2004 after a large-scale retreat of the Taliban following the US troops invasion in Afghanistan, were among the first to fall under the influence of IS [8]. Although based in Waziristan all through these years, former members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and the Islamic Movement of Turkestan (IMT) maintained close ties with al-Qaeda and irregular international Islamist organizations. Feeling the effects of the “Pashtun chauvinism” victim complex reigning in the Taliban, they did not hesitate to cooperate with ISIS and became the core of that same cohort, which was mobilized to participate in the fighting in Iraq and Syria. Having been cut off from their land for many years, they are a universal tool and a major asset that can be used with equal effectiveness in Af-Pak, the Middle East and Central Asia.

As it currently stands, the Islamic State has failed to overcome the mutual distrust among its actual and potential supporters, who used to make up the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban. The mechanisms to overcome tribal rivalries within the Pashtun ethnic group as well as general mistrust of other ethno-linguistic groups towards the Pashtuns were not found [9]. In fact, the central government in Raqqa did not put its agents in Khorasan to this task, which is added testimony to the minor importance attached by IS to this line of action and significantly reduces the likelihood of the latter’s genuine involvement in local conflicts and relationship system. Mobilization, organizational and other mechanisms that have demonstrated their efficiency in Iraq and Syria, proved to be inadequate amidst South and Central Asian realities, so the emergence of a mass movement similar to the one on the Arab land was impossible there.

Andrey Sushentsov, Nikita Mendkovich:

New Spiral of Afghanistan Crisis and Russia’s

Interests

“Paper Tiger” is a win-win deal

Nevertheless, the illusory presence of ISIS in Afghanistan suits the interests of nearly all regional actors. For supporters of the central government the world’s attention to everything that is associated with the Islamic State is currently an effective tool to enlist additional support for the fight against the Taliban, which is a much more real and apparent threat to the Kabul regime. In turn, the Taliban, being separated and fragmented due to the current political leadership crisis and lack of effective management, benefits from IS terrorist activities, its conflict-ridden relationship with the latter notwithstanding. ISIS readiness to take responsibility even for acts of terrorism and sabotage, which it did not commit, gives the leaders of the Taliban freedom in their “parochial diplomacy” with the local elites and governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan without genuine renunciation of the effective use of force and violence. Since the Islamic State has neither real economic, social and political institutions, in the region nor significant military resources, it cannot provide keen and tough competition for the Taliban, as well as for many other political forces in their struggle for power and domination in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the very presence of ISIS in Afghanistan allows Raqqa to receive from the country what it has always been after, namely the reputational dividends from projecting its influence, and human resources for the war in other areas of the “global jihad,” including Europe.

Operating on the premise that there are many natives from Af-Pak and Central Asia in the ranks of both supporters and opponents of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, the problem of IS for Afghans has more than one dimension. Moreover, the war on the side of ISIS or against it offers many ordinary Afghans just another way out of the vicious circle of permanent conflict and endless civil wars that have destroyed the statehood and economy of their country. Thousands of Afghan refugees and displaced persons have joined the flow of migrants from Asia and Africa to Europe in search of a better life, using for their own purposes the IS presence in Afghanistan to legitimize their selfish by nature, but quite natural under the circumstances, intentions to migrate to the developed Western countries.

Hence, no matter how illusory, lacking substance and insensitive to local conditions and specificity the activity of ISIS in Afghanistan might be in the foreseeable future, we have to acknowledge and take into account that it naturally meets the needs of a wide range of parties and therefore remains relevant and viable in its hybrid form in the medium term.

1. The Khorasan province covers the territory of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the surrounding areas of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, the western region of China (XUAR), the northern states of India (Jammu and Kashmir) and Bangladesh.

2. For details see: Bunzel C. From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State // The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. Analysis Paper. 19 March 2015.

3. Rafiq A. Op. cit.

4. Zahid F., Khan M.I. Prospects for the Islamic State in Pakistan // Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. 1 April 2016.

5. J. Kepel. Jihad. The Expansion and Decline of Islam // Moscow, Ladomir Publishers, 2004, pp. 218-219. [in Russian]

6. For details see: Behuria A.K. Sects Within Sect: The Case of Deobandi–Barelvi Encounter in Pakistan // Strategic Analysis. 2008. Vol. 32. Iss. 1. Pp. 57-80; Masooda B. Rational Believer: Choices and Decisions in the Madrassas of Pakistan. Cornell University Press, 2012.

7. Ahl al-Sunnah wa'l-Jamaah // The Oxford Dictionary of Islam / ed. by J. L. Esposito. Oxford University Press, 2003 [Online edition].

8. Zahid F., Khan M.I. Op. cit.

9. Op. cit. // Sahifa At-Takrir. 23 June 2015.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |