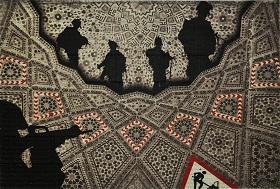

The problem of overcoming postmodernism, mainly in the Middle East, is analyzed in the article “The Middle East: Postmodernism Is Over.”

The exhaustion of the postmodern paradigm of social existence marks the emergence of a new epoch, which can be defined as the era of neomodernism. The uncertainty of its contours notwithstanding, it indicates quite vividly a modernist request for a “new gravity,” which is conveyed by postmodern technologies and practices.

In her comment, Elena Alekseenkova entered a third variable into the equation, namely “premodernism.” The elegance of this intellectual somersault allows us to reduce the issue under discussion to the problem of social archaization. While agreeing that today postmodern social consciousness represents a melting pot of archaic practices, symbols and values that are becoming part of the overall game, nevertheless, I emphasize the fact that this game has acquired quite a modernistic gravity.

The principal difference between the current state of the Middle East and the pre-modern one is that the archaic narrative (and not only archaic) is not initially given (as in the case of genuine premodernism), but results from a conscious choice, while the latter is a modernist phenomenon.

Therefore, we can return to the initial thesis.

What neomodernism leaves unsaid

So, let’s assume that postmodern consciousness, which exists in the “do not worry, be happy” paradigm, cannot provide answers to the challenges faced by the Middle East. However, it creates conditions for implementing all the elements into a single narrative, and this represents its greatest potential.

There is little doubt that inventing such a narrative arbitrarily from without is less than likely, and its emergence will be the finale of the present Middle East drama.

However, since the problems have to be solved by means of this narrative, we can distinguish certain aspects of the latter.

Obviously, the first such problem is what V. Naumkin called curing the “diseases of society” that push young people to radical ideologies.

Accordingly, the question arises: What do young men and women that travel to the Islamic State seek? The answer is not a riddle wrapped up in an enigma.

Young people discussed it in 2011 on Tunisia’s central Bourguiba Avenue and Egypt’s Tahrir Square. Freedom, justice, and dignity were the three most popular words of the Arab Spring. One of the participants of the revolution, coming from the outskirts of Tunisia’s capital, phrased its main message as follows: “make passport tearing impossible for any flick.”

The matter at issue is an efficient state and the integration of the majority into the political and economic system. The same was true for Peru during the time of rampant Sendero Luminoso, described by Hernando de Soto in his book The Other Path and other works.

To achieve this goal, intellectuals will have to articulate a strategic vision for the national future (the most important element of the above narrative), while Middle East politicians will have to change the attitude towards their own societies and embark on the road of structural political and economic reforms.

If they fail to take this path, they will face an unenviable future, and neither Russia, nor the United States, nor anyone else will be able to help them. The maxim, known to every Soviet TV viewer that one cannot make people happy against their will, is the lesson to be learned by the Western world from the colonialism of the past and interventionism of recent years.

If the request for change in the Arab countries maintains its relevancy (it is already being witnessed in Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and, in a way, Morocco), the extra-regional powers will have to fundamentally reshape their Middle East policies.

This will create conditions for a harmonious interconnection of the region with the outside world. Irrespective of the specific content of the grand Middle Eastern narrative in the neomodern era, it will not develop into a global confrontational alternative, the likelihood of which is already observed today.

Apparently, the promotion of structural reforms in the countries of the region, considerate assistance in enhancing the inclusiveness of their political systems, while recognizing their authenticity, support for measures aimed at the socio-economic integration of their societies and the strengthening of institutions should be the main objectives of the new Middle East strategy of extra-regional actors.

Given the common interest of the United States, Russia and the EU in stabilizing the situation, reducing the level of political violence in the Middle East and establishing a self-sufficient system of regional security, cooperation among them is possible. As the example of Syria shows, this is already underway, but so far has been limited to resolving urgent and more or less local problems. Apart from working out common approaches and a unified action strategy, developing this cooperation necessitates the normalization of relations between global leaders, the rejection of the Cold War configuration in the Russian-American relations, and, most importantly, the awareness of the Kremlin and the White House of the horrors of the possible alternatives.

Philosophy prompts action

With regard to specific measures for strengthening and developing the region, there seem to be five areas of interaction that appear to be relevant.

First, the three hottest conflicts in Syria, Yemen and Libya should be localized, de-escalated and subsequently resolved. If today in Syria there is some progress, the situation in Yemen and Libya shows no signs of success. Moreover, as far as Libya is concerned, nobody has the slightest idea what institutions can launch the political process there. Experience has shown that outside attempts to form a unity government bear no fruit and local forces are far from willing to search for a compromise.

In addition, another escalation of two old conflicts, namely between Israel and Palestine and in Western Sahara, is not just possible but more than likely. This is evidenced, on the one hand, by a wave of terrorist attacks that have swept across Israel in recent months, and on another hand, by heightened tensions around Western Sahara, brought about by Ban Ki-moon’s visit to the refugee camp.

The second area of interaction is to work out a program and specific mechanisms for the post-conflict development of the regions concerned, their economic revival and communities’ rehabilitation. The matter at issue here is not so much the source of covering the relevant expenses, as a way to organize recovery institutions and the targeted use of resources.

It is clear that in Syria the list of potential donors will largely depend on a number of aspects, including: the configuration of the political transition; who will lead the country during this period and how; what opposition representatives will be included in the transitional power structures; the resolution of the problem of the territorial-administrative division of the Republic; how transitional justice will be done, etc. Given the painful process of the political settlement, it makes sense to explore the possibility of making the socio-economic recovery at least partially independent from the above settlement. Understandably, such a recovery will have to rely on existing government mechanisms and, therefore, requires Russia’s active participation.

How to solve other no less important problems (the return of refugees and their reintegration, demilitarization of the population, quelling day-to-day violence, preventing endless blood feuds, and communities’ rehabilitation in general) is anything but certain.

The third area of interaction involves strengthening the institutions of “fragile states.” It is not enough to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 2015 to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet and announce Tunisia as a democratic transition model for the region. Similarly, it’s not enough to congratulate the Egyptians for successful elections and opening the New Suez Canal. Both countries should continue to enjoy economic support, and mechanisms are required to encourage the enhancement of their systems’ inclusivity and further genuine social reforms.

In terms of importance, the socio-economic sphere here is second to none. The wide-spread belief that the wave of mass protest in Tunisia and Egypt was triggered largely by a high unemployment rate does not seem quite relevant today. In fact, the majority of formally unemployed “angry youth” had been employed in the informal economy, which, in terms of volume, was just as large as the legal one, and in some parts of these countries (for example in the border-zone) accounted for up to 80 percent of the entire economy. Accordingly, the social justice that these people crave for should not be understood in the leftist paternalistic way. It implies, above all, creating conditions for doing business legally, increased social mobility and broader political participation.

Fourth, Algeria and Saudi Arabia, the key states that could potentially face destabilization, need support and strengthening. They both have to enhance their institutions, and in both countries the situation is complicated by the fact that the international community has little to offer the governments of these states. However, the younger generation of leaders coming to power in Saudi Arabia seems to realize the need for change and institutional development, which a large-scale program of reforms announced by Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud testifies to.

Finally, knowledge-based cooperation could become the fifth area of interaction. By combining openness of liberalism with prudent caution of conservatism in their dialogue, the West and Russia could launch and maintain a multi-vector dialogue among intellectuals on the future of the Middle East region.

This consistent interaction of global actors in the described areas could have a significant positive impact on both the Middle East and their own relationship. It can establish the basis for forming the neomodern narrative, which was discussed in the beginning of the article.

What role can Russia play in all this?

To be sure, the brilliant diplomacy and powerful Air Forces may be helpful in matters of conflict resolution. However, the other items on the agenda will demand completely different involvement, resources and skills. What is more important, they will require a global strategic vision.

The future of the boosted “Russia’s return to the Middle East,” the fate of the Middle East, and, quite possibly, the fate of Russia and the West are up to our ability to meet these demands.