The development of the political dialogue between China and India has been impeded by the frozen border conflict that could escalate into a major clash. But we should not exaggerate the threat of military confrontation between Beijing and Delhi, since their strategic interests are so far in sync.

This year India and China celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between Tibet Region of China and India and the declaration of the Panchsheel five principles of peaceful coexistence between the two countries, a honeymoon in relations that was followed by the 1961 border war. Today, the 1954 Panchsheel Treaty and its principles are interest more for historians rather than for policymakers of the two countries. What should we expect from the two Asian giants – a normalization in their bilateral relationship or the escalation of the border dispute into a wider military-political confrontation?

The Glacier of Discord

The 2000s were marked by an abundance of forecasts about looming global competition and a military showdown between India and China. The two states may indeed clash in the future, but the conflict will be caused by their border dispute rather than their rising international ambitions, as are often presented by the Western media. It is not an overstatement to note that accidental circumstances have played a major role in the Chinese-Indian relationship, its trajectory often defined not by the top politicians in offices, but rather on the top of the world, i.e. the Himalayan division line between the two armies.

As a matter of fact, the two Asian giants have quarreled about two territories, one of them Aksai Chin in the border's western sector, which is an unlivable 38,000-square-kilomters chain of glaciers amid a salt desert at 4,500-7,000 kilometers above the sea level. The second territory is Arunachal Pradesh located in the eastern portion of the borderline, a northeastern Indian state with an area of 84,000 square kilometers and a population of 1.4 million intersected by the Himalayas and covered by thick forests. The western area is virtually governed by China, while India insists that Aksai Chin is a part of Ladakh district in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. The eastern territory is under Indian control but claimed by China.

The two states were doomed to collide over these lands back in the colonial era, the conflict surfacing in 1914 when the British Indian administration used China's weakness to impose a border treaty in order to delineate its holdings and essentially independent Tibet. Chinese negotiators who were invited had no levers to change the situation, which resulted in the Simla Accord that established the India-Tibet frontier along the McMahon Line. As a result, British India acquired the territory of the former Tibetan principality Ladakh, including Aksai Chin, as well as the northeastern areas, i.e. the North-East Frontier Agency, which were converted into the state of Arunachal Pradesh after India became independent.

The Delhi-Beijing controversy erupted in 1950 when Tibet became a part of China and the Chinese army took over control of the Indian border. True to the principles of anti-colonialism and cherishing friendship with its northern neighbor, Jawaharlal Nehru recognized China's right to rule over Tibet. This step regrettably drove India into a disadvantaged position because it allowed for a revision of the borders. China has never recognized the McMahon Line, convinced that Tibet, a part of China, had no sovereignty and thus no right to sign the Simla Accord.

In the fall of 1962, the dispute broke out into a border war that was catastrophic for the Indian army. Aksai Chin was occupied by the Chinese, with Arunachal Pradesh remaining Indian. The troops of the two states were divided by their actual line of control. For India, the damage was to a large extent reputational and had a healthy sobering effect that led to a revision in its approach to its northern neighbor.

Cold Peace

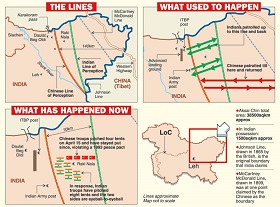

Although attempts at a settlement were made in the 1990s and 2000s, armed clashes along the line of control occurred nonstop, the latest in April 2013 when a Chinese platoon crossed the border and camped on Indian territory for a month. The incident pushed the sides to sign the Border Defense Cooperation Agreement of October 2013 that specifies basically new principles for settling border conflicts, shifting the appropriate powers from the top brass to the political leaders of the two countries.

With border clashes much less frequent, battles on geographical maps are not abating. In June 2014, almost immediately after the Chinese foreign minister's visit to Delhi, Chinese cartographers (who have done much to help Beijing spoil relations with all its neighbors) published a new map of the Peoples' Republic of China with Arunachal Pradesh shown as part of Chinese territory, only undermining mutual trust at a time of numerous statements about the quick settlement of the conflict.

Although entirely useless as an economic entity, Aksai Chin is extremely important for China in military terms because of the road linking Xinxiang Uyghur Autonomous Region with Tibet. At first glance, the generation of pragmatic leaders led by Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi, both of them more focused towards the economy, sees few barriers to putting an end to the extended territorial dispute, with the solution lying in mutual concessions. New Delhi should give up its claims to Aksai Chin, an important demand for China, while Beijing should drop claims for Arunachal Pradesh already developed by Indians. But it was Pakistan that has virtually ruled out the settlement options.

In 1963, Islamabad, led by General Muhammad Ayub Khan, signed a border agreement with Beijing conceding part of Kashmir including Ladakh. The move caused indignation in India since Pakistan not just gave away to China a part of Kashmir whose entire territory is claimed by India as its own, but also legitimated the presence of Chinese soldiers in the area isolated from India in 1962, even though Pakistan never had had any control over the territory. Thanks to oriental craftsmanship, Islamabad acquired a powerful ally in Beijing by linking the India-China border dispute with the Kashmir issue. By ceding Aksai Chin to China, Islamabad expected India to automatically recognize Pakistan's sovereignty over a part of Kashmir, something no Indian government would do no matter how pragmatic it might seem.

Military Strategic Rivalry

The India-China territorial dispute has been definitely aggravated by the fact that both are nuclear powers. Due to the threat emanating from officially nuclear China, India (deprived of the right to have such under the NPT Treaty) has grown into a systemic violator of the international regime for the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

In view of the use of nuclear weapons, the India-Pakistan confrontation is believed to be most dangerous, while the Indian nuclear program is seen rather as a response to the Chinese threat. Delhi prevails over Islamabad in conventional assets, while a nuclear strike against Pakistan would have catastrophic consequences for India.

Notably, the Indian nuclear program is focused on advancing delivery systems rather than on the number warheads, having allowed Pakistan to lead in this area. Similar to Beijing, New Delhi is about to join Moscow and Washington in possessing the nuclear triad. In June 2014, India began testing its first ICBM submarine Arihant. In 2013, India successfully tested its first ICBM Agni-V fit that can hit any target on Chinese territory, while medium-range missiles and tactical bombers appear to be sufficient to deter Pakistan.

Hence, there is every reason to speak of a regional arms race, although an arms purchase race seems a wording more appropriate for India. For any kind of weapons from decommissioned aircraft carriers to firearms, India can easily compete with American Christmas sales in terms of volume and speed, since New Delhi has been so far unable to establish a defense sector of its own.

Of special importance are the navies of the two countries. The String of Pearls, or the Chinese maritime doctrine, provides for the erection of naval bases along critical sea lanes used to deliver oil to the Celestial Empire from the Persian Gulf. To this end, India is worried about being literally surrounded by Chinese military facilities that include the deepwater port Gwadar in Pakistan, early warning systems in Myanmar, and the future port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka. Unable to respond in kind, New Delhi relies on the aircraft carriers and in 2013, matched Beijing in tonnage of aircraft cruisers and went ahead in terms of new contracts.

Is Asia in for a Cold War?

No wonder that many pundits predict an India-China cold war. However, more detailed analysis reveals absolutely no analogy with the confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States. Neighboring countries, especially those with smoldering territorial disputes cannot but heed their reciprocal military capabilities, something that at the same time triggers upward trends in their defense budgets. However, the two seem to be in different weight classes, since China's military spending in 2013 was USD 180 billion (a 170-percent growth since 2004), whereas the Indian defense budget was only USD 47.4 billion, having risen just by 45 percent during the same period. Hence, speaking about an arms race appears to be too early because India is still too slow in trying to catch up with its rival.

Nuclear containment Asian-style is fundamentally different from the Soviet-American experience, because the two countries have pledged "no first use" of nuclear weapons and their assets are not battle-ready.

The establishment of opposing blocs led by China and India also appears unlikely, since their less powerful neighbors are not wary about their economic and military feats. Disagreements in Asia are so acute that military coalitions will be set up only by the United States which allies with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and the Philippines. Beginning in 2007, Washington has been devising a new mechanism for military interaction in the Indian and the Pacific oceans, ostensibly to contain China's rising naval power. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue brings together the navies of the U.S.A., Australia, Japan and India, which hold consultations and joint exercises. But New Delhi, a staunch nonalignment proponent, is unlikely to jump into the American system of security arrangements in Asia-Pacific.

Likely Allies?

What Beijing and New Delhi lack in order to plunge into a cold war is ideological confrontation. Viewed beyond the confines of Asia, where their interests clash head on, their relationship appears to be all harmony and mutual understanding. China and India present a united front on most global issues, working to grab their place in the sun from their industrialized rivals. Beijing and New Delhi share a multipolar approach to global governance, are trying to revise the existing system of international financial institutions, and table similar demands at the WTO multilateral talks. On the whole, they agree on climate change, energy security, the predominance of international law and many other global problems.

China and India will not be content with regional power status, regarding themselves in the same category as other global leaders. Therefore, at this stage, they appear rather as natural allies interested in revising the existing world order. It seems hardly proper to insist that the two will enter into an overall confrontation similar to the Soviet-American cold war, since neither side boasts the resources and influence required for such kind of bilateral relations. Nevertheless, common strategic goals notwithstanding, China and India might well plunge into an armed border conflict that would not evolve into large-scale war because their leaders are very well aware of subsequent consequences for their recent national economic achievements, and after which both would be left with insufficient resources for claiming anything more substantial than the Himalayan glaciers.