Every year on August 15 the world’s largest democracy celebrates its Independence Day. India is the fastest growing economy after China. But what drives its growth and how will the country’s economic policy change after the election of the new Prime Minister, Narendra Modi? We asked Andrei Volodin, Senior Research Fellow at Eurasian Studies Centre, Institute of Current International Problems’ at the Russian Foreign Ministry Diplomatic Academy, to comment the situation.

Interview

Every year on August 15 the world’s largest democracy celebrates its Independence Day. India is the fastest growing economy after China. But what drives its growth and how will the country’s economic policy change after the election of the new Prime Minister, Narendra Modi? We asked Andrei Volodin, Senior Research Fellow at Eurasian Studies Centre, Institute of Current International Problems’ at the Russian Foreign Ministry Diplomatic Academy, to comment the situation.

Are there any concrete plans of transforming the Indian economy on the basis of the experience of the state of Gujarat? What exactly is the new Prime Minister Narendra Modi planning to do?

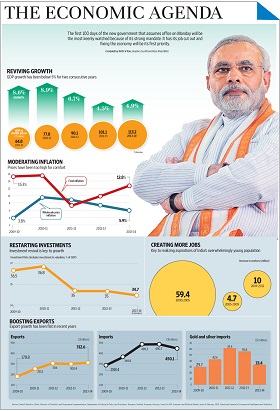

The new Indian prime minister intends to put the administrative apparatus in order. Gujarat has been growing very fast, at a rate of 12 per cent on an annual basis. It is a comparatively small state and spreading its experience to the rest of the country is a challenge. India is one of the countries with wide gaps between different sections of the population in terms of socio-economic and cultural development and the level of political inclusion. Nevertheless, the outlines of his programme have been appearing in the press and can be gleaned from conversations with informed people from India. First of all, Modi speaks of a return to the subject of development. For me, development means a high rate of economic growth. He will try to push the growth rate to the all-time high of 8–9 per cent. The rest will depend on the state of the Indian economy and on whether the conditions of world trade favour development. Development is impossible without economic growth.

The second point in the development strategy is the problem of employment. And here the experience of Gujarat merits attention. Narendra Modi will try to spread it gradually throughout the country through pilot projects. What does this mean? Developing countries (including India) are seeing a migration of the rural population to the cities in search of employment. Modi proposes to improve people’s living conditions by implementing social and infrastructure programmes in rural areas in order to reduce the effect of over-urbanization (the phenomenon of a significant proportion of the rural population not finding a place in modern industrial production and turning into outcasts or lumpenproletariat). This is the first important part of Modi’s future strategy.

The second element is the re-industrialization of India, which will take into account the interests of the private-corporate sector and those of the state, because the state must play the key role at the tail end of the first stage and the start of the second stage of reforms. This is not to say that the state intends to issue directives. This is strategic planning or, as they say in the West, indicative planning when production clusters are selected that would spearhead the country’s scientific and technical progress, with the state stimulating the development of these areas. Indian business will be involved in the implementation of the programme. Business structures are good at working with cutting-edge technologies. Narendra Modi can ensure partnership between the state and the private corporate sector, especially because he has the successful experience of Gujarat to fall back on.

How is he Indian Government planning to attract new foreign investors into the economy? What are the priority sectors?

In my opinion, the People’s Republic of China is a very important partner for India. This is despite the military clashes of October 1962, which have etched themselves onto the historical memory of the Indian people. Trade between India and China is substantial and China is India’s biggest trading partner. China is ready to help India set up an industrial and transport infrastructure and invest in the creation of industrial corridors all over the country. For China it is a lucrative investment, especially since many countries today are trying to shed their one-sided dependence on the U.S. dollar. During Dmitry Rogozin’s visit to Delhi in June 2014, India expressed an interest in extending the Russia–China gas pipeline to the border with India. India would then be able to get gas through Eurasian pipeline networks without being dependent on gas transportation and the condition of the seas and oceans, which is very important for Indian foreign economic policy. As for specific industries and stimulating sectors and clusters of industry, the planning commission is working on that.

While Indian agriculture employs a colossal number of people its share in the economy is not so great. Does Mr. Modi intend to reform the agricultural sector?

Reform of the agricultural sector is a fairly vague way of describing the problem. This is not just about giving all peasants plots of land and providing them with equipment. Because India has a monsoon climate, this is also about the assistance of the state or private banks (public-private partnership will get a new boost in India) and providing cheap institutional loans. The aim of reform is to keep farmers in agriculture and to avoid large-scale “de-peasantization.” The rate of economic growth in agriculture should be at least 5 per cent. At this rate, India would be able to develop, create buffer stocks of grain against natural and climate fluctuations and feel more confident in the WTO. The dispute over easing the terms of trade initiated by India (the negotiations have been ongoing for 8–9 years) indicate that the government is trying to protect its agricultural sector. This is not surprising because a large – if not the main – share of the population lives in rural areas, and the majority of the economically active population is still employed in the agricultural sector. These people should be given work and they should ensure India’s food security. The reform is seen here as a series of measures aimed at improving the effectiveness of agriculture’s.

How is India planning to develop economic ties with China and how is cross-border trade faring considering the border disputes between the two countries?

The border incidents should not be overdramatized. Mr. Modi pointedly conducted his election campaign in the state of Arunachal-Pradesh, which historically has been disputed between India and China. The origins of the territorial dispute go back to the times when a treaty was signed delimiting China and India within the British Empire.

China is not overreacting to this. For China, concrete actions and India’s wish to implement reform and improve political links with China matter more. Trade and economic links are successful, and that includes cross-border trade. The frequent exchange of political barbs need not apply to the entire range of Sino-Indian relations. Surely, there are conservative circles in India and China that mistrust each other. But the policy is determined by the states’ leaders, and Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi have defined the vector of the development of Sino-Indian relations, which is to strengthen bilateral cooperation considering the fact that the world is entering a dangerous phase of transition from one type of political relations to another. Closer cooperation between India and China takes on added importance today. The interaction between India and China may create favourable external conditions after the withdrawal of American and other Western forces from Afghanistan. This is one of the factors that may ensure the unity and territorial integrity of Afghanistan after the withdrawal of the coalition forces in 2014.

Interviewer by Maria Gurova, RIAC Programme Assistant