International agenda on climate change: what are the prospects for a new treaty?

Campaign against global warming, in

downtown Warsaw, 2013

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD University of Cambridge, Researcher, Centre for Energy, Climate and Environmental Law, University of Eastern Finland; consultant at the International Institute for Sustainable Development

Climate change has risen to the top of the international agenda and is a regular item under consideration at major international arenas including the UN, G8, and G20. Yet, available international instruments like the Kyoto Protocol have proved to be ineffective in substantially reducing global emissions and on-going negotiations on a new UN treaty have so far been protracted and yielded only modest results.

Climate change has risen to the top of the international agenda and is a regular item under consideration at major international arenas including the UN, G8, and G20. Yet, available international instruments like the Kyoto Protocol have proved to be ineffective in substantially reducing global emissions and on-going negotiations on a new UN treaty have so far been protracted and yielded only modest results. Climate change thus serves as a textbook example of the Tragedy of the Commons where individual countries prefer to pursue short-term economic interests overusing a common good, even though everyone will be worse off in the long-term. An annual UN summit on climate change convened in Warsaw on 11-23 November 2013 provided another illustration of this with a dramatic standstill between industrialised and developing countries in its last meeting.

This article reviews the current international agenda on climate change, starting with the latest findings on climate science. It then offers an analysis of existing international instruments such as the Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol, and the state of the UN negotiations on a new treaty. The article continues with an examination of the relevance of the discussions for Russia and concludes by exploring prospects for a new UN agreement as well as climate mitigation efforts beyond the UN.

Carbon budget and planetary limits

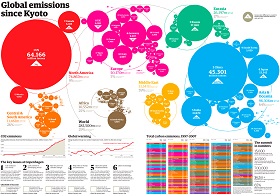

As a result of limited participation, the Kyoto Protocol currently covers only 13% of global emissions which is deeply inadequate for solving the problem of global climate change.

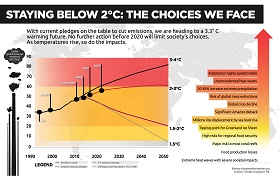

Global emissions of greenhouse gases are rising every year, and the link between these and rising temperatures has been proven. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a UN body completing scientific assessments, recently concluded that current atmospheric concentrations of the three most powerful greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide – are unprecedented in at least the last 800 000 years. The global average temperature has already increased by 0.85 degrees since 1880. The current consensus among UN nations based on scientific research is that any temperature increase above 2 degrees Celsius around the world compared to pre-industrial levels is too dangerous, for it will lead to profound, irreversible and costly negative effects on the environment, population and economies worldwide.

The IPCC also concluded that to stay below 2 degrees the cumulative carbon dioxide emissions have to remain at 1000 petagrams of carbon. This is the planet’s carbon budget, which cannot be exhausted. Yet, as of 2011, already more than half of the budget has been used up and if the global economy continues developing in a carbon-intensive way, the world is on the track to exceed its carbon budget by 2045.

The energy sector is the largest sector responsible for the most of emissions: in 2010 it accounted for two-thirds of the global total. Carbon dioxide (CO2) from the burning of fossil fuels constitutes about 90% of energy-related greenhouse gases, with about 9% attributed to methane.

As to how global emissions are distributed among individual nations, historically, industrialised countries have contributed the most, but recently large emerging economies have been catching up owing to their rapid development. In 2012, already 60% of all global emissions originated in non-OECD countries, with China being the top emitter and India coming third, after the US.

UN Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol

In 1992, nations agreed on the need for international action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to impacts of climate change under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Convention, which enjoys nearly universal participation, is very generic in nature as it does not set concrete obligations for reducing emissions within the countries which ratified it. However, in 1997 the Convention was complemented by the Kyoto Protocol which established detailed legally-binding commitments for industrialised countries to reduce greenhouse gas from 2008-2012 (Kyoto-1). In 2012, nations also negotiated the extension of the Protocol for 2013-2020 (Kyoto-2).

The Protocol however proved to be ineffective for the purpose of significantly reducing global emissions, since it only imposed emission reduction targets on industrialised countries. The US, the industrialised country with the largest share of global emissions, signed but never ratified the agreement owing to a change of presidential administration and difficulties in agreeing domestically to internationally set commitments which do not cover emerging economies. That top-down nature of the Protocol where target-setting and compliance control are managed at the international level in the same way as for industrialised countries would also be hard to digest for large developing countries with growing emissions like China and India. As a result of limited participation, the Kyoto Protocol currently covers only 13% of global emissions which is deeply inadequate for solving the problem of global climate change. Therefore, a conceptually new international agreement was needed to ensure that all main greenhouse gas emitters around the world lower their emissions.

Negotiations on a new UN treaty on climate change

Negotiations on a new treaty commenced already in 2007, culminating in a dramatic meeting of world leaders in late 2009 in Copenhagen. This meeting has been frequently described as a diplomatic impasse, ending in procedural scandals, mutual accusations and a failure to formalise whatever little and abstract was possible to agree on. Regardless, its substantive outcomes provided a framework for further decisions and importantly for a formal Working Group launched in 2011 to negotiate details of a new UN treaty on climate change. This treaty is scheduled to be adopted in 2015 in Paris and, allowing for a lengthy process of national ratifications, enter into force in 2020.

Despite apparent difficulties in reaching interim milestones, the prospects for a new treaty are encouraging, as negotiations on its concept and various elements have been taking place for years now. There is certainly more mutual understanding on the positions of major players on the outlook of a future regime. A new agreement will be more comprehensive in addressing not only carbon mitigation but also adaptation, technology transfers, financial assistance, and capacity-building.

For reducing emissions, a new treaty, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, will apply to all countries including the US, China, India and others. The main question is: to what extent mitigation actions will be binding or not for individual countries, and how they will differ, if at all, for developed and developing countries. China, India, Brazil and other large emerging economies firmly believe that historical responsibility for current climate change lies with the industrialised world, which should adopt ambitious commitments to reduce their emissions. They also point out that despite their growing economies emissions per capita are still much lower than those of industrialised countries and that economic growth is absolutely vital for them to address multiple development challenges. On the other side, industrialised countries argue that the world economy has dramatically changed in the last decades and cumulative emissions of developing countries would soon equal to those of developed countries. In their view, all countries regardless of their status under the Convention adopt some type of commitment to reduce emissions for a new treaty to be effective. This conceptual division between developed and developing countries is fundamental for understanding the many hurdles of the negotiations on a new treaty.

It is clear that the new agreement will take a bottom-up approach to national emission reductions where countries decide themselves on their appropriate emission reduction targets, schedule and actions, as opposed to the top-down approach of Kyoto Protocol. These national emission reductions are then supposedly assessed at the UN level; though the exact nature and purposes of such assessment are unclear at this point.

Overall, it is clear that the new agreement will take a bottom-up approach to national emission reductions where countries decide themselves on their appropriate emission reduction targets, schedule and actions, as opposed to the top-down approach of Kyoto Protocol. These national emission reductions are then supposedly assessed at the UN level; though the exact nature and purposes of such assessment are unclear at this point. More than 90 countries have already submitted their pledges to reduce emissions by 2020 under the previous Convention’s decisions covering about 80% of total emissions. While such a bottom-up approach is more agreeable to all countries, its ultimate effectiveness for slowing down the growth of global emissions is questionable. The existing pledges mentioned above vary heavily in nature and form, making them difficult to compare. Most of them are non-binding, and even if all are implemented as planned, they would not be sufficient for ensuring the temperature increase stays below two degrees.

Reducing emissions is only part of the story. The negative impacts of climate change are already occurring in all parts of the world, but are not evenly distributed. Countries most vulnerable to a sea-level rise, droughts, floods, and the loss of land suitable for agriculture are often the poorest and have little capacity to deal with, or prepare for, adverse impacts. The November summit in Warsaw was held in the aftermath of typhoon Haiyan with some scientists labelling it as the most powerful typhoon ever to have reached land. The tropical cyclone claimed thousands of lives, left millions displaced and caused massive destruction in the coastal areas of the Philippines. Although scientists are still unsure about the higher frequency of tropical cyclones in a warmer world, they do warn that tropical cyclones will increase in their intensity. This dimension gives another angle to the notion of historical responsibility and the divide between developed and developing countries in the UN negotiations where this time developing countries are represented by poorer nations. These nations not only demand immediate and ambitious emission reductions from industrialised countries to stop global warming but also financial assistance in helping them adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change. In 2010, parties to the Convention established a Green Climate Fund to provide financial assistance for mitigation and adaptation in developing countries. Until now, various arrangements to make the Fund operational have been under discussion but against the backdrop of the financial crisis, the main question of the money to fill the Fund in still remains an issue.

Energy Revolution. XXI century. Reset

Against this background, where does the recent Warsaw meeting stand? The meeting was an interim event on the pathway to a Paris agreement about whose achievements the media reports were mostly sceptical. Indeed, on the outside, the summit did not seem to meet its high expectations, with emotional drama and a charged politicised atmosphere accompanying the entire event and the last discussion taking the form of a sleepless marathon overrunning the scheduled time of completion by some 24+ hours. Yet, despite these challenges, some tangible decisions were made. Parties agreed to establish a results-based financing framework for the protection of tropical forests, which serve as important carbon sinks. More than a hundred million US dollars were pledged by industrialised countries to fund adaptation projects in developing countries. The two issues causing the most heated debates related to a loss and damage mechanism, and a roadmap to a Paris agreement. On the former issue, poor nations effectively demanded that developed countries take up liability for any losses and damages occurring as a result of adverse effects from climate change, for example flooding or sea-level rise. This would potentially lead to multiple legal claims for compensation for the loss of territories, infrastructure or income. Such an interpretation was opposed by the developed countries which preferred to consider loss and damage as part of adaptation to climate change, rather than liability. Although compromise language was found in the end to get the mechanism in principle going, the contradiction did not dissolve and will surface again in discussions. As for a roadmap to a Paris agreement, a last minute deal was also negotiated to invite all countries to submit their domestically defined emission reduction pledges in early 2015. However, fundamental questions remain unanswered as to: (1) the nature, form and timeline of these targets as well as their international review; (2) whether developed and developing countries will be ready to commit to reducing their emissions on equal legal terms; and (3) to what extent the future treaty will be legally binding.

Relevance for Russia: “nothing to do with me” approach?

Reducing emissions is only part of the story. The negative impacts of climate change are already occurring in all parts of the world, but are not evenly distributed.

Russia is a somewhat strange partner in international climate diplomacy as technically it belongs to the camp of neither industrialised countries nor developing countries. Formally, in the company of the former, Russia enjoys a special status of an “economy in transition” meaning that its obligations to reduce emissions should be more flexible and it does not have to provide finance for developing countries in the same way as developed nations. Indeed, the country’s emissions shrunk by nearly 40% in 1990s owing to the post-Soviet collapse of its economy and industry. Despite this, the country remains one of the major greenhouse gas emitters in the world.

In Kyoto-1, Russia’s target for reducing emissions meant in fact not exceeding a certain level of emissions rather than real emissions reductions, since the goal was defined in relation to the pre-collapse 1990 year. For Kyoto-2, Russia did not sign up due to perceptions about its ineffectiveness in solving the climate change problem and the need to focus on a new comprehensive treaty applicable to all major emitters.

Domestically, climate change has never received appropriate attention at the policy level in Russia owing to: the marginalised status of environmental issues in general; the massive role of fossil fuels in its economy; limited knowledge and often mere ignorance about the science of climate change and available climate policy options; and a firm, though unfounded, belief that climate change if anything will bring only benefits (see below). Although Russia has adopted a series of relevant policy and legislative documents such as the Climate Doctrine and a recent presidential decree enforcing the emissions target for 2020, these have remained mainly declarative in nature and led to little follow-up action. Russian policy-makers have so far been unable to see benefits and opportunities opening up by shifting to a low-carbon economy, including clean energy markets, green innovation, and carbon pricing instruments.

At the same time, decarbonisation policies in the energy sector like phasing out inefficient coal power plants, increasing energy efficiency and developing renewable energy have multiple economic, energy security and environmental co-benefits and do not need to be driven by climate considerations as such. The energy efficiency potential of the Russian economy is estimated at a massive figure of 45%. Realising this potential would not only increase the competitiveness of the economy (as well as free up more fossil fuels for export) but also lead to significant emission reductions: the State Programme on Energy Efficiency and Development of the Energy Sector adopted in 2013 estimates reductions of 393 million tons of CO2eq by 2020 as a result of the measures envisaged in the programme. In the end, for climate change, it matters little what the driving factor is behind increasing energy efficiency if it leads to the same set of climate-related benefits.

On the impacts’ side, Russian policy-makers frequently display confidence that climate change impacts will be positive for the country, referring to new opportunities for resource exploration and transportation in the thawing Arctic, new lands for agriculture and less fuel needed for district heating in winter. Available expert analyses however paint a different picture: Roshydromet concluded that the majority of climate change impacts in Russia will be negative for economy development and public health, because the benefits mentioned above come alongside with an increase of extreme weather and climate events like droughts, floods and heat waves, damage to infrastructure and communications in Northern Russia due to permafrost degradation, and species displacement. Ignoring the climate change factor in adaptation planning can lead to huge economic losses: damages from forest fires during the unusually hot summer of 2010 are estimated at about 500 billions rubles, or 1.2 % of the Russian GDP at the time.

In international climate diplomacy, Russia’s wait-and-see position is also narrow-minded. Without active participation in shaping a climate policy framework, Russia risks staying behind the development of carbon regulations and related clean energy markets while locking its own future in inefficient and carbon-intensive infrastructure, processes and technologies. Its political ambitions for global power status also require a more active role on issues of global concern. Russia could further consider taking a stronger interest in discussions on climate finance as it can assist countries of political or economic interest with climate adaptation projects making aid money more visible and leveraging on such linkages.

Conclusions: looking beyond the UN

In international climate diplomacy, Russia’s wait-and-see position is also narrow-minded. Without active participation in shaping a climate policy framework, Russia risks staying behind the development of carbon regulations and related clean energy markets while locking its own future in inefficient and carbon-intensive infrastructure, processes and technologies.

Many argue that the UN has failed in its role in addressing the climate change problem by not delivering tangible outcomes over several years of intensive negotiations. However, the UN can only do as much as its members are willing to do. One also should not forget that global climate policy is no longer confined to the realm of the UN regime and a plethora of other supranational, national and sub-national initiatives are underway around the world. The US and China, the top two emitters of greenhouse gases, have launched bilateral work on developing initiatives to reduce carbon emissions from heavy duty vehicles, buildings, manufacturing and coal-fired power, for example by advancing smart grids and carbon capture and storage. China, facing public pressure to reduce air pollution in its cities, has launched ambitious plans to cut back emissions. It is also the world’s largest investor in renewable energy development and clean energy R&D. Overall, clean energy investments are substantial around the world with prices of renewable energy technologies falling. On the US side, the shale gas revolution and a coal-to-gas shift are contributing to the country’s lower emissions: in 2012 energy-related CO2 emissions decreased by some 3.8% compared to the previous year.

Interest in carbon markets is rising worldwide as a policy tool to reduce greenhouse gas emissions with both national and sub-national schemes already operating in the EU, China, California, Japan, Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea, and others, and many more in a design phase. The UN Climate and Clean Air Coalition for phasing out short-lived climate pollutants is active too. Its main focus is on black carbon (soot), methane and tropospheric ozone which not only contribute to rising temperatures but also negatively impact public health, agriculture, food production and ecosystems.

Despite these multiple arenas for reducing greenhouse emissions, there still needs to be a global framework for catalysing and coordinating climate action and ensuring it is sufficient for slowing down emissions growth as well as helping the most vulnerable countries cope with adverse consequences. The on-going negotiation process under the UN will probably result in some type of a treaty on climate change by the end of 2015. However, given profound conceptual disagreements between industrialised and developing countries and the fact that so far the decisions have been made on the basis of the lowest common denominator, it is doubtful that this treaty will become an effective international instrument for preventing dangerous climate change.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |