The Myanmar Perestroika

Myanmar's Military Commander in Chief Senior

General Min Aung Hlaing, Speaker of the Upper

House of Parliament Mahn Win Khaing Than,

Vice President Henry Van Thio, State Counsellor

Aung San Suu Kyi, President Htin Kyaw,

Vice President Myint Swe and former vice president

Sai Mauk Kham pose for a photo with ethnic leaders

after the opening ceremony of the 21st Century Panglong

Conference in Naypyitaw, Myanmar August 31, 2016

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Russian Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, RIAC Member, RIAC Vice-President

Serious changes are taking place in Myanmar. The military regime that had been in power since 1962 was replaced with a civil government. Today, Myanmar essentially has two centres of power: representatives of the former democratic opposition headed by Aung San Suu Kyi and representatives of the former military top brass which have suppressed this opposition for decades. The country’s future hinges on whether the former rivals will be able to unite their efforts to overcome the current challenges: to achieve reconciliation between the centre and the ethnic outlying districts, settle the Muslim question and suppress drug trafficking.

Serious changes are taking place in Myanmar. The military regime that had been in power since 1962 was replaced with a civil government.

During the first years of its independence, Myanmar played an active part in international affairs. Myanmar is a Buddhist country, and its foreign policy was based on Buddhist precepts: rely on your own power, adhere to the middle way and avoid extremes. Myanmar kept an equal distance from global blocs, advocating the Pancha Shila, or the five precepts of peaceful co-existence, which endowed it with significant international prestige. In 1961, Myanmar diplomat U Thant became the third Secretary-General of the United Nations.

However, after the military coup of 1962, Myanmar found itself by the wayside of international politics, due both to self-imposed isolation in foreign politics in the 1960s–1980s, and a long list of sanctions imposed on Myanmar by the West, primarily the United States in the 1990s under the pretext of human rights violations committed by the military regime.

A Long Way to Changes

Self-imposed isolation and Western sanctions seriously damaged Myanmar’s economy. When Myanmar joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in late 1997, its military leaders could not fail to see that their country lagged behind its neighbours, Thailand and Malaysia. At the same time, the western political and economic blockade tied Myanmar to China tighter and tighter, and Myanmar’s subordinate position in this bilateral pairing antagonized the country’s nationalists. The only way to follow the middle way in foreign politics and balance China’s pull and repair relations with the West was to establish a dialogue with the civil opposition.

Myanmar’s generals took their time studying the experience of their neighbours – primarily Thailand and Indonesia – of transitioning from authoritarian rule to more liberal governance. A new constitution was developed over the course of 20 years; it was intended to pave the way for multi-party elections and at the same time ensure that the military top brass retain their control over the political process which the Yangon strategists named a “Discipline-Flourishing Democracy.” In 2008, the draft constitution was put to a referendum, and was approved by 92 per cent of the voters (with a voter turnout of 98.1 per cent). In November 2010, the country held general elections. Myanmar’s “democracy icon” Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of Myanmar national hero General Aung San, who was leader of the oppositional National League for Democracy (NLD) and a Nobel Peace Prize winner, was released from her years-long house arrest. During the first session of the central parliament in January–February 2011, the Assembly of the Union (since October 2010, the country’s official name is the Republic of the Union of Myanmar) elected the heads of executive, legislative and judiciary bodies.

Thein Sein, a retired general, became President. He immediately set out to implement a broad range of political and economic reforms. The head of the military regime, Senior General Than Shwe, retired, and Min Aung Hlaing (his successor as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces), the minister of defence and other generals now reported to the new and formally civil authorities.

Are the Generals Really no Longer in Power?

Six out of eleven members of the National Defence and Security Council headed by the President represent the army.

During the five years between the elections of 2010 and 2015, new shifts in the power balance occurred. At the 2015 general elections, the formerly oppositional NLD party scored a landslide victory, winning 58 per cent of seats (225 out of 440) in the lower chamber (House of Representatives), 60 per cent (135 out of 224) in the upper chamber (House of Nationalities) of the Assembly of the Union, and 55 per cent of the seats in regional legislatures. It gave the NLD the opportunity to vote through its candidate for presidency. Aung San Suu Kyi was at the peak of her popularity, but she could not become the first non-military president since the 1962 military coup. Her husband was a British national, and her two sons have British citizenship, and under the Myanmar Constitution, people with close relatives who are foreign citizens cannot hold the office of the president. Under the circumstances, the winning party had only one way out: to appoint a “proxy president” who would be guided by Aung San Suu Kyi. Aung San Suu Kyi chose her childhood friend, 70-year-old Htin Kyaw, a little-known writer and university professor. He joined the NLD only two months before the presidential elections, but he immediately became a member of the Office of the NLD Chairperson.

However, the generals have not completely abandoned state governance. Under the 2008 Constitution, 25 per cent of the seats in the bicameral Assembly of the Union and in Myanmar’s 14 regional legislatures are reserved for the Army’s representatives, who vote as a bloc as ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. As Htin Kyaw was sworn in as President, Lieutenant General Myint Swe, a representative of the military faction, assumed the office of the First Vice President. According to the Constitution, the Commander-in-Chief also appoints the three power ministers (Minister of Defence, Minister of Home Affairs and Minister of Border Affairs). Six out of eleven members of the National Defence and Security Council headed by the President represent the army.

Myanmar’s generals retained powerful levers of both political and economic power. For instance, two extremely influential economic bodies, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (UMEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) are subordinated to the Ministry of Defence. They were created on the basis of enterprises formerly owned by the state. The UMEHL controls the mining industry, including the mining of rubies, sapphires and jade, which ensures a sizable influx of foreign currency. What is more, the UMEHL plays a significant role in banking, tourism, real estate, transportation, consumer goods manufacturing and the food industry, including beer brewing.

Thus, Myanmar has a system of governance that takes into account both the principles of western democracy and the role of Myanmar’s army in the life of country.

But to what degree is the NLD ready and able to work within such a model? Initially, the party was an assembly of small democratic groups united by their resentment towards the military regime. Its electoral campaigning and propaganda boiled down to the call upon fellow citizens to make Aung San Suu Kyi the leader of the country. Few people abroad and in Myanmar itself had ever heard of any eminent comrades-in-arms of the “democracy icon.” The situation with democracy within the NLD itself is sufficiently described by the fact that no member of the Assembly of the Union has the right to give interviews to the media; this right is reserved for Aung San Suu Kyi only.

Myanmar has a system of governance that takes into account both the principles of western democracy and the role of Myanmar’s army in the life of country.

The NLD’s leader initially took over four ministerial offices: the head of the presidential administration, the minister of foreign affairs, the minister of education, and the minister of electricity and energy. She determines appointments in the entire government machine. How efficient will this machine be given the cult of personality of this leader, who is not exactly a spring chicken (Suu Kyi was born in 1945)?

How to Ensure the Country’s Unity?

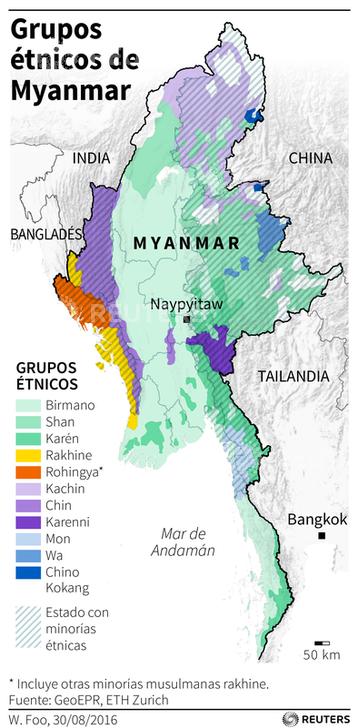

The principal problem that Myanmar has faced since gaining independence is ensuring the country’s unity. Myanmar is a multi-ethnic state. About 70 per cent of its population are Burmese (their self-appellation is the Bamar), and over a quarter of its population comes from other ethnic groups. Seven states that span over half of the country’s territory and have significant natural resources are populated mostly by non-Burmese ethnicities. During the entire period of independence, these states were the hotbed of separatism and riots.

The military regime managed to mitigate the situation. In some cases, rebel units were crushed in military actions, in others, a ceasefire was achieved in exchange for special autonomous status for several small ethnicities. Before the 2015 general elections, 8 out of 15 armed groups of ethnic insurgents signed a ceasefire agreement with the administration of the former president Thein Sein, and this agreement made it possible to conduct political dialogue and include other insurgent groups in this dialogue [1].

Yet the largest and best-armed groups, the United Wa State Army and the Kachin Independence Army did not sign the agreement. One of the stumbling blocks was that the groups signing the agreement had to formally agree with the articles of the 2008 Constitution, and all these groups demanded that powers and revenues from the use of natural resources be redistributed between the centre and the states.

Recently, the poppy fields have grown in size and opium production has risen as well.

At the 2015 elections, for the first time in the history of Myanmar, the majority of voters in the regions populated mostly by ethnic minorities cast their ballots not in support of the local, so-called ethnic parties, but in support of the national NLD, hoping that it would be able to solve the accumulated problems. The NLD, in turn, announced its course for interaction with the ethnic and religious minorities and proposed Henry Van Thio, a native of Chin State and a Christian, for the office of Second Vice President. At the same time, the ruling party has yet to come up with a clear programme to solve the ethnic question.

Drug Trafficking

Solving the ethnic question in Myanmar is inextricably linked with fighting drug trafficking. The northeast of the country, together with the adjacent territories of Thailand and Laos, is part of the so-called Golden Triangle [2].

Shan State accounts for 92 per cent of the opium poppy grown in the “Golden Triangle.” In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the previous military regime, using both stick (armed crackdowns on separatist drug traffickers) and carrot (economic stimulation for peasants who abandon growing poppies for other crops) ensured a stable decrease in opium production in Myanmar. Between 1996 and 2004, the fields for growing poppies dropped in size from 160,000 hectares to 44,000 hectares. However, recently, the poppy fields have grown in size (to 55,000 hectares in 2015), and opium production has risen as well. In 2004, Myanmar produced 370 tonnes of opium; in 2015, it produced 730 tonnes. Relaxed control on the part of the security, defence and law enforcement agencies under the transition to civil governance undoubtedly played a role in this development.

The Muslim Question

Finding an answer to the Muslim question is also becoming more urgent. As we have already noted, Myanmar is a Buddhist country. Still, there is also a Muslim population, formed mostly by descendants of settlers from India and Bangladesh. Official statistics number them at about 4 per cent of the population, unofficial data estimates up to 10 per cent.

The so-called Rohingya problem has recently also exacerbated. The Rohingya people are ethnic Bengalis who live mostly in the north of Myanmar’s Rakhine State on the border with Bangladesh. They differ sharply from the Rakhine and the Burmese in appearance, language, culture, and religion, and at the same time, they are virtually indistinguishable from Bengalis living in the southeast of Bangladesh in Chittagong. NGOs estimate that there are about 800,000 Rohingyas, while people continue to enter from Bangladesh, and the birth rate in these enclaves is up to 10–12 children per adult female.

Yangon’s previous military regime justly feared that Rakhine State might turn into Myanmar’s Kosovo and refused to recognize the Rohingya people as citizens of Myanmar. The Myanmar authorities find the word “Rohingya” itself unacceptable; it appeared just half a century ago and is derived from the name of Rakhine State in Myanmar and seems to indicate that the Rohingya people are natives of the region. International humanitarian organizations condemned the military regime for restricting the rights of the Rohingya people, which made them more confident in their confrontation with the Myanmar authorities and its citizens in general.

All this has produced a peculiar kind of Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar, which has been stoked by both the military regime and the opposition. For instance, during the “Saffron Revolution” of 2007, thousands of Buddhist monks wearing traditional saffron robes took to the streets of Yangon with anti-government slogans. The so-called Buddhist Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, the most radical organization of Buddhist nationalists, demands the legal restriction of the rights not only of the Rohingya people, but of all Muslims in Myanmar.

The so-called Rohingya problem has recently also exacerbated.

It is worth noting that Aung San Suu Kyi, just like the previous military regime, does not recognize the Rohingya people as Myanmar citizens. She publicly addressed the U.S. Ambassador requesting that he stop using the term “Rohingya” in his speeches on the situation of Muslims in Myanmar. This immediately gave rise to a wave of publications in western media accusing Suu Kyi of dictatorship and racism.

Revitalizing External Contacts

The United States is exhibiting a growing interest in Myanmar. In 2011, Washington restored full-fledged diplomatic relations with the country (with the military regime in power, the embassy was headed by a chargé d’affaires ad interim). The United States and the European Union lifted economic sanctions, leaving just the prohibition on military and technical cooperation in place. President Barack Obama has visited Myanmar on two occasions (in 2012 and in 2014). Other U.S. officials, including Secretary of State John Kerry, visit the country as well.

At the same time, U.S. business still largely neglects Myanmar. As of August 2014, the total amount of U.S. investments did not exceed $250 million. Some analysts explain this by civil instability, but there are other reasons as well.

In 2012, Barack Obama allowed U.S. companies to invest in Myanmar, but forbade them from dealing with economic bodies that have ties with the military, for instance, the UMEHL and MEC. Ignoring this rule is punishable with a fine of up to one million dollars or a prison term of up to 20 years. However, this prohibition may be circumvented: American entrepreneurs register companies in Singapore and then invest hundreds of millions of dollars in Myanmar.

Companies from other countries do not have such difficulties and they come to Myanmar on their own. In 2016, Japan’s Nissan plans to open a plant with the Malaysian Tan Chong Motor Group manufacturing Sunny compact sedans in Bago Region.

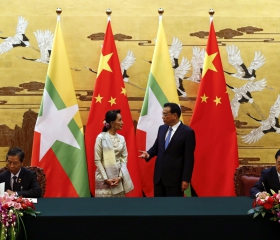

One of the subjects Wang Yi discussed in Naypyidaw was the promise to assist in achieving a peaceful settlement with ethnic insurgents in the northeast of Myanmar, which is one of the new government’s priorities.

An economic recovery is taking shape in Myanmar. In 2015, Myanmar ranked 13th in the world in terms of its economic growth. In the early 2016, the country’s first Yangon Exchange started trading.

The Chinese Factor

In many respects, the Chinese factor plays a defining role in Myanmar’s affairs. China accounts for 42 per cent of foreign investments into the country, a total of $33.67 billion in 1988–2013, as well as 60 per cent of imported weapons and military equipment for the Myanmar Armed Forces.

Myanmar is also China’s gateway to the Indian Ocean. China depends heavily on oil supplies, primarily from the Persian Gulf countries and Africa, which account for the largest share of China’s oil and gas imports. Previously, oil and gas were shipped via the Indian Ocean and the narrow Strait of Malacca which the ships of the United States Seventh Fleet based in the region can block quite easily. Today, pipelines running through Myanmar give China direct access to the Indian Ocean. Thus, in 2013, a pipeline with a capacity of 12 billion cubic metres became operational, transporting gas from the Myanmar Shwe gas field on the coast of Rakhine State to China’s Yunnan province. In January 2015, an oil terminal owned by China’s CNPC became operational in the deep-water port of Kyaukphu in Rakhine State. The 771-kilometre main pipeline, which runs from the terminal into China parallel to the previously built gas pipeline, has a capacity of up to 400,000 barrels per day. Annually, this is about 8 per cent of all the oil imported by China.

The implementation of these projects has allowed thousands of kilometres of the transportation route to be cut out when transporting hydrocarbons from the Middle East and Africa, and thus decrease expenses, as well as make the delivery process safer. What is more, developing the Myanmar transportation corridor has allowed China to solve other tasks as well; for instance, developing the country’s inner provinces, which previously did not have access to the ocean and, consequently, to foreign markets. China intends to use the Kyaukpyu port for both large LNG-transporting vessels and large Panamax class container vessels to export Chinese commodities.

The rapprochement between Myanmar and the United States after 2011 coincided with the previous Myanmar government’s suspending, under the pretext of local public protests, such joint Myanmar–China projects as the Myitsone Dam (worth $3.6 billion), the Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Yunnan–Rakhine railway (worth $20 billion). This was a cause for concern in Beijing. It was no coincidence, therefore, that the first foreign guest to visit Naypyidaw – just five days after the new government of Myanmar was sworn in – was Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic of China Wang Yi, invited by the new Minister of Foreign Affairs of Myanmar Aung San Suu Kyi. The visit served to further Beijing’s dialogue with the NLD, which began in 2015 when Aung San Suu Kyi visited China (she was then received by President Xi Jinping).

Wang Yi’s visit took place just as the Myanmar Investment Commission approved the agreement between China’s state company Guangdong Zhenrong Energyand several Myanmar businesses to build a $3-billion oil refinery in the city of Dawei in the southeast of Myanmar.

It should be noted that one of the subjects Wang Yi discussed in Naypyidaw was the promise to assist in achieving a peaceful settlement with ethnic insurgents in the northeast of Myanmar, which is one of the new government’s priorities. Given China’s historic ties with ethnic minorities in the region, Beijing can definitely play a significant role here. An ethnic conflict in Myanmar runs contrary to China’s interests: in order to implement its economic projects of moving towards the Indian Ocean and the “one belt, one road” initiative, China needs peace and security in Myanmar’s border regions and close cooperation with the central government in Naypyidaw. By promoting a peaceful accord between the central government and the ethnic insurgents and by expressing its willingness to act as a kind of a guarantor of such an accord, China strives to improve relations with the NLD government and retain its influence in Myanmar.

India’s Interests

India also wishes to become an important partner of Myanmar. Three weeks after Wang Yi, the Minister of External Affairs of the Government of India Sushma Swaraj visited Naypyidaw. New Delhi has long maintained working relations with the previous military regime, and now it hopes to use Myanmar as a gateway to the ASEAN. Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi is transforming the Look East Policy proclaimed by New Delhi into Act East Policy.

The country’s future hinges on whether the former rivals will be able to unite their efforts to overcome the current challenges.

India attempts to compete with China in the region, and watches with concern China–Bangladesh cooperation gathering pace, and India responds by intensifying contacts with the countries within Beijing’s sphere of influence, primarily Myanmar, but also Thailand and Vietnam. India also has a logistical need of Myanmar. On the one hand, Myanmar is the only land “bridge” connecting India to the markets of Southeast Asia. On the other hand, Myanmar is a convenient way to deliver commodities to India’s north-eastern regions. In 2008, India and Myanmar agreed to construct a four-lane, 3,200-kilometre highway connecting the two countries with Thailand (the project is scheduled for completion in 2016). In mid-October 2011, India announced its intention to give Myanmar a $500,000-million loan to develop infrastructure projects. In particular, $136,000 million were allocated for the construction of a deep-water port by Essar Group in Sittwe in Rakhine State. It is intended to become a starting point for the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project to India’s north-eastern Mizoram state.

India is also interested in cooperation with Myanmar in ensuring security in its north-eastern states that border Myanmar. According to the available information, the separatists who are active in those states (in particular, the Naga separatists) are supported by their fellow tribesmen in Myanmar.

Russia–Myanmar

Today, Russia is turning to the east, and partnership with Myanmar is important in strengthening peace and security in the Asia Pacific.

Positive progress has been made in recent decades in bilateral cooperation. In 2014, the Intergovernmental Commission on Trade and Economic Cooperation was formed, and its first meeting was held in August 2014 in Naypyidaw. In November 2015, the first stage of an ironworks construction was completed in Taunggyi (Shan State); it is being built with the technical assistance of Russia’s Tyazhpromexport.

The Russia–Myanmar Mixed Commission on Military Technical Cooperation formed in 2000 is functioning successfully. The Myanmar Armed Forces use Russian MiG-29 aircraft, Mi-17 and Mi-24 helicopters and S-125 surface-to-air missile systems. In 2016, Myanmar acquired Yak-130 fighter trainer aircraft. Myanmar officers study in Russian military academies. On May 11, 2016, the lower chamber of the Myanmar parliament unanimously approved a new Russia–Myanmar draft agreement on military cooperation submitted to the parliament by the Myanmar Armed Forces.

Educational ties are also expanding. Since 2001, the Myanmar government has paid for about 4,000 undergraduate and graduate students to study at Russian universities. Since 2014, young Myanmar citizens have been eligible for state scholarships from the Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States, Compatriots Living Abroad and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo).

* * *

The processes taking place in Myanmar open up broad prospects in both domestic and foreign politics. The country has the potential to make a comeback to the international arena as an influential political and economic actor. However, thus far we are talking prospects only: there are grounds for Myanmar to be reborn on the basis of democratic principles, but there is no solid, firm foundation yet. Today, Myanmar essentially has two centres of power: representatives of the former democratic opposition headed by Aung San Suu Kyi and representatives of the former military top brass which have suppressed this opposition for decades. The country’s future hinges on whether the former rivals will be able to unite their efforts to overcome the current challenges: to achieve reconciliation between the centre and the ethnic outlying districts, settle the Muslim question and suppress drug trafficking.

Not a single foreign power – neither China, nor the ASEAN partners, nor the West – wants Myanmar to turn into yet another hotbed of international tensions, and this works in favour of the country’s new government. Myanmar’s emergence from isolation, its socioeconomic revival and its becoming a full-fledged member of the international dialogue would be good for peace and security in Southeast Asia and beyond.

1. Among those groups who signed the agreement are the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Restoration Council of Shan State. They have fought against Myanmar’s central government for over 60 years and have never before entered into any agreements with it.

2. The Golden Triangle is a geographical area which includes the mountainous regions of Thailand, Myanmar and Laos; in the mid-20th century, it evolved a system of opium production and trade with organized crime syndicates linked to the local and global elites.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |