(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Lead researcher and head of the Peace and Conflict Studies Unit at the Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) in Moscow

Amid the vast ocean of Islamist radicalism, the particular focus given to Islamic State (IS) is merited by its role as the main center of gravity in the transformation of transnational violent jihadism today. Before exploring how this phenomenon is linked to and affects Russia in and beyond the North Caucasus and in the broader Eurasian context, and before examining the character, scale and the contextual limits of such links, it makes sense reflect on IS itself and the plethora of views and interpretations of this movement.

Amid the vast ocean of Islamist radicalism, the particular focus given to Islamic State (IS) is merited by its role as the main center of gravity in the transformation of transnational violent jihadism today. Before exploring how this phenomenon is linked to and affects Russia in and beyond the North Caucasus and in the broader Eurasian context, and before examining the character, scale and the contextual limits of such links, it makes sense reflect on IS itself and the plethora of views and interpretations of this movement.

IS stands out even among the world’s most lethal Islamist or jihadi groups. Not only is it extremely radical in outlook and methods, it is also a quasi-army that has become the main combatant in the world’s two most intense and deadly conflicts, is proving resilient to countermeasures and is capable of launching and conducting offensive military operations in two different theaters simultaneously (as illustrated by its advances on Ramadi in Iraq’s Anbar province and on Palmyra in Syria in May 2015). In addition to combat activity, IS, according to Global Terrorism Dataset, conducted more terrorist attacks against non-combatants than any other group in 2014 [1]. It is also a magnet for the largest flow of foreign jihadi fighters since the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan — in fact, by some accounts, it is already exceeding the latter in scale. No less importantly, IS has a solid financial basis and is running its own state-building experiment that, in ideological terms, claims the legacy of the “Islamic Caliphate” and, in practical terms, is a nascent quasi-administration trying to deliver basic governance. It is gradually becoming a transnational migration or settler project, with IS-controlled lands being positioned as the number one destination for disenchanted Muslims of various degrees of radicalism, largely civilians from different parts of the world.

In addition to combat activity, IS, according to Global Terrorism Dataset, conducted more terrorist attacks against non-combatants than any other group in 2014.

There are many ways to explain the IS phenomenon. One approach, suggested here, is that IS/ISIS strikes right at the interface of what may be the two main trends in the evolution of transnational violent jihadism today [2].

The first trend is the “regionalization” of transnational jihadism. While this has been a mainstream trend for years, in previous decades it was mostly seen as top-down regionalization (a shift in the center of gravity of the al-Qaeda-inspired “global jihad” movement into the al-Qaeda regional affiliates in several Muslim regions — the Arabian peninsula, the “Islamic Maghreb” etc.). In contrast, what we see today is increasingly a bottom-up regionalization process (with the Near Eastern region and IS phenomenon in Iraq-Syria as its main focal points).

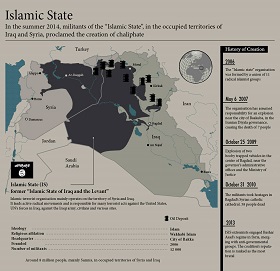

Infographics. Islamic State

It is gradually becoming a transnational migration or settler project, with IS-controlled lands being positioned as the number one destination for disenchanted Muslims of various degrees of radicalism, largely civilians from different parts of the world.

The second, parallel trend is that of the network fragmentation of the “global jihad” movement — the emergence of small, semi- or fully autonomous, self-generating homegrown jihadi cells around the world, often linked to the “movement” and to each other primarily or solely by “global jihad” ideology, but seeing themselves and planning and undertaking terrorist attacks as part of a global network. While such fragmented cells can be found in over 70 countries, they are most active and most closely associated with homegrown, transnationally-inspired, jihadi terrorism in the West.

These two trends are inter-related, but distinct. They develop in parallel, and only partially overlap. It is precisely where they most closely overlap that the IS phenomenon has formed.

Some experts emphasize, often excessively, another trend in transnational violent jihadism — namely, competition and outbidding between IS and al-Qaeda. Indeed, there are some important ideological and practical distinctions between the two. In contrast to al-Qaeda and its followers, IS does not see the “Islamic Caliphate” as an abstract, distant, extraterritorial and utopian end-goal. Instead, it is building a physical, territorially-based Islamist Caliphate here and now, in its own region. Both the IS version of the Caliphate and its general appeal are considerably more populist and grass-roots in nature, at least in its own sectarian context (a kind of “people’s Caliphate” for disenchanted Sunni Muslims), as opposed to al-Qaeda’s relatively elitist message and structure (based on Sayyed Qutb’s vision of elitist Islamist vanguard cells purifying themselves of the “ocean” of ignorant and materialistic “masses”). In a sense, the IS phenomenon can be seen as a continuation, in a different context, of the transnational jihadi movement embodied by Palestinian Abdullah Azzam (a key ideologue and practitioner of “global jihad” who fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan and emphasized mass armed resistance “in defense of Muslim lands” and who offered a much more populist agenda). This approach contrasted with that of Osama bin Laden — an elitist, globally-oriented financial mediator and coordinator of jihad in Afghanistan who, following the death of the more popular Azzam in 1989, inherited and led what remained of the existing transnational jihadi networks and transformed them into what later became al-Qaeda.

Some experts emphasize, often excessively, another trend in transnational violent jihadism — namely, competition and outbidding between IS and al-Qaeda. Indeed, there are some important ideological and practical distinctions between the two.

Sporadic political and military tensions between these two approaches can be seen occasionally on the ground in Iraq and Syria, including in the form of violent clashes between groups affiliated with IS and al-Qaeda. Also, like waves, these rifts project themselves into other, more distant conflict areas, catalyzing new splits among violent Islamists in places ranging from Afghanistan to Russia’s North Caucasus. However, in practical terms, these nuances should not be overestimated: even in the Iraq-Syria context, operational alliances between groups loyal to al-Qaeda and IS are not infrequent on the ground.

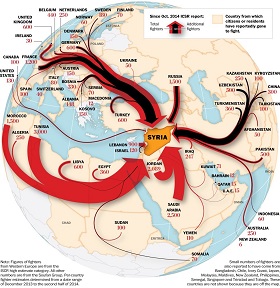

More importantly, this obsession with the idea of competition and a kind of bidding war between al-Qaeda/affiliates and IS may distract us from the more critical issue. IS did not emerge as a global phenomenon — it emerged as a regional movement, driven by regional dynamics and regional conflicts (including those unleashed by, and as a reaction to, external intervention), enabled and facilitated by the weakness of states of the region, and fueled by and fueling regional sectarianism. What made this regional phenomenon become part of “global jihad” as a movement and ideology is precisely the mass influx of foreign “global jihad” fighters. In this respect, the inflow of jihadis from the West, who, with their markedly, explicitly globalist agenda and universalist outlook, provide IS with its main link to “global jihad” (even as they may comprise no more than a quarter of all foreign fighters) plays a crucial role. As for militants from various local fronts — both from Muslim states in the broader Middle East (who make up a majority of foreign fighters) and from areas of low-intensity, Islamist-separatist conflicts on the periphery of Muslim-minority states in Asia and Eurasia (including Russia’s North Caucasus) — they appear to be more in demand on the ground, in the battlefield.

IS and Russia

Foreign fighters flow to Syria

In recent years, the main source of Islamist violence in Russia — the conflict in the North Caucasus — has lost the international focus it once had as a major jihadi battleground. This reflects the realities on the ground. The main specifics of the Russian/North Caucasus case were the highly controversial effects of the gradual jihadization of the originally mainly ethno-separatist insurgency on the militant movement, the conflict dynamics, and the broader region. Some of these effects catalyzed the rise of local traditionalist, non-jihadi ethno-religious forces that ultimately opted for an alliance with Moscow. In combination with the federal policy of Chechenization, and massive reconstruction assistance, this allowed Russia to gradually reduce the major armed conflict in the North Caucasus to a peripheral one by the early 2010s, and to decrease the intensity and scale of both combat and terrorist operations. As a result, the conflict in the North Caucasus since the late 2000s has been reduced to a “minor” one in the world’s specialized datasets on armed conflicts [3]. According to the latest Global Terrorism Index (2014) [4], Russia, for the first time in the 21st century, was no longer in the Top 10 of the world’s most terrorism-affected countries (where it had previously occupied the 9th place, for the period 2002–2011, i.e. the first post-9/11 decade) [5].

Against this background, it has been in Russia’s very genuine interests to ensure that the relative stabilization in its North Caucasus region — achieved at a very high cost — is not distorted, undermined, or reversed, by new destabilizing transnational links, actualized by the Syria-Iraq context and especially by the IS phenomenon. While, for a time, foreign radical Islamist influences appeared to be in decline in Russia, violent jihadism may be making a comeback due in part to the presence of some fighters from Russia and other post-parts of post-Soviet Eurasia in radical Islamist groups in the Syria-Iraq theater, including IS — although they are a minority compared to, for instance, Western jihadis in the same theater.

IS — North Caucasus

Some of these effects catalyzed the rise of local traditionalist, non-jihadi ethno-religious forces that ultimately opted for an alliance with Moscow.

The immediate concern is the actual movement of Islamist militants and implications of the potential return of some of them for militant/terrorist activity in the North Caucasus. While few extremists from the North Caucasus fought on the side of the radical armed opposition in Syria even before the declaration of the formation of the IS, they (and, to a lesser extent, fighters from elsewhere in Russia) became more numerous and active in IS, groups that have, fully or partly, aligned to or declared loyalty to IS (such as “Jaish al-Muhajireen val’Ansar” — “battalion of migrants” — in Syria) and other radical Islamist militant groups (including IS’ local rival/counterpart “Jaish an-Nusrah”). According to the Russian officials, their overall numbers already stood at 300-400 in Syria in 2013 [6], increasing to 800 in 2014 and potentially amounting to 1700 in Iraq alone in early 2015 [7].

Some of these fighters, including several top commanders, are ethnic Chechens, but come from other parts of the Caucasus (i.e. Georgia). A significant proportion comprises émigré militants of North Caucasus origin who come from third countries, ranging from Turkey and the Middle East to Europe (including younger people who grew up and were radicalized in the diaspora). While many still come from various different parts of the North Caucasus (by various routes, but ultimately usually via Turkey — a connection facilitated by the visa-free regime and the volatile situation on the Turkish-Syrian border), some experts estimate that only about 150 actually come from Chechnya itself [8]. IS needs militants from the region, primarily because of their fighting skills and experience, as well as their relative autonomy from local clans and interests that increases its operational flexibility. They, in turn, are attracted by the prospect of fighting at the center and cutting edge of jihadism for a territorially based, well-funded Caliphate, rather than as a marginalized semi-virtual underground movement operating under rigid security pressures on the periphery of a powerful, fully functional and consolidated Muslim-minority state.

It has been in Russia’s very genuine interests to ensure that the relative stabilization in its North Caucasus region — achieved at a very high cost — is not distorted, undermined, or reversed, by new destabilizing transnational links, actualized by the Syria-Iraq context and especially by the IS phenomenon.

Domestically, the main problem in the region so far has been less one of returning fighters as such, than one of pledges of support for IS by local field commanders, radical clerics and mini-jamaats. The latter mostly act “out of weakness” rather than “out of strength”, in the hope of gaining additional legitimization by associating themselves with IS successes and of gaining clout and perhaps assistance from violent Islamist groups in the Near Eastern theater. This trend, however, has had controversial implications for the violent underground. It both fuelled struggles for influence between figures and groups claiming loyalty to IS and those adhering to the old loose umbrella framework of “Imarat Kavkaz” and even saw internal tensions and splits even among those who declared loyalty to IS. In fact, in the short term, these internal struggles weakened the Imarat’s new leadership (Aliazkhab Kebekov, a.k.a. Ali Abu Mohammad ad-Dagestani, who had succeeded Imarat’s first leader Doku Umarov after the latter’s death reported in early 2014), and aided the authorities in their efforts to eliminate him (killed in April 2015). Remarkably, the Imarat’s leadership has even expressed its own reservations about fighters leaving for the Near East as diverting manpower from the local insurgency (and also diminishing their own control and clout).

The main problem in the region so far has been less one of returning fighters as such, than one of pledges of support for IS by local field commanders, radical clerics and mini-jamaats.

Any mass return of fighters to wreak havoc may so far remain more of a possibility than a reality, but it is still a matter of serious concern. It is automatically accepted that the North Caucasus, especially beyond Chechnya, would be a natural place for them to return to, where they would then try to reignite and upgrade the heavily fragmented underground of mini-jamaats scattered across the region). However, the federal containment strategy and security pressures within the region impose strict limits on this return flow, which could amount to another complicating factor.

IS and Islamist radicalization beyond the North Caucasus

The outflow of actual and potential militants from Russia to Syria and Iraq is not confined to those from the North Caucasus or of the North Caucasus origin and includes radical Muslims from the Volga region [9], the Urals, and elsewhere in Russia. This is just one manifestation of a limited, but disturbing phenomenon — the emergence of autonomous radicalized Islamist cells and individuals across Russia, with members increasingly drawn from among non-North Caucasus Muslims and even ethnic Russian converts to Islam. While this radicalization does not always or necessarily take violent form, it creates the setting and the pool for some members to join or be recruited into violent activities at home or abroad. While some may be linked to North Caucasus counterparts (e.g., in preparation of the 2013 bombings in Volgograd), others display no direct link to the North Caucasus context or agenda [10]. Such radicalization often, although not exclusively, involves urban, relatively well-educated young people (including young women, as highlighted by the recent and ongoing cases of Moscow students Varvara Karaulova and Maryam Ismailova).

In certain ways, some of these radicalized cells and individuals appear to more closely resemble self-generating jihadi cells in Europe than the North Caucasus underground (even if they are still much fewer than homegrown European jihadi cells). Remarkably, this type of cell, not mired in the North Caucasus’ contextual dynamics, is in fact more likely to develop an interest in the ideology and agenda of the “global” versions of Islamist jihadism. They also appear to have a better grasp of transnational jihadi propaganda, increasingly spread through modern information and communication channels and involving more markedly transnationally-minded popularizers or preachers. In Russia, this trend was set by a native Siberian convert to Islam, Said Buryatski (killed in 2010) who made a point of reaching out to new audiences, such as educated urban youth across the country.

Any mass return of fighters to wreak havoc may so far remain more of a possibility than a reality, but it is still a matter of serious concern.

Given this trend, there might also be some demand for potential jihadi returnees from the Syria-Iraq context from radicalized elements in Russia beyond the North Caucasus. In another similarity to Western European “homegrown” jihadi cells — and in contrast to the North Caucasus militants — these radicalized cells and individuals elsewhere in Russia tend display a mismatch between high ideological ambition and limited capacity and qualification to carry out violent/terrorist activity — a gap that the returning jihadis may help bridge.

Finally, as noted above, Russia does not exist in a vacuum — it is an integral part (arguably the core) of a broader Eurasia, which is central to its multilateral regional cooperation, integration efforts, and regional security strategies. The same transnational influences and connections, including those related to IS and the Syria-Iraq theater, that affect Russia are also relevant to its Eurasian/CIS partners [11]. Eurasia, and especially Central Asia, is also the source of the major transit of people into and out of Russia. While the religious/ideological radicalization of Russia’s large labor migrant community of Muslims from Central Asian countries has not yet become a major social phenomenon (as is typical for first-generation migrants anywhere who tend to be largely preoccupied with immediate economic survival strategies), the problem of managing informal migration, including from Muslim regions, has become one of the dominant issues in Russian society and national politics. Any attempts to manipulate this issue for Islamist radicalization purposes in connection with the IS phenomenon (e.g., the May 2015 call by Tajik IS member, ex-colonel Khalimov, for Tajik migrants in Russia to join IS) should be countered and prevented at almost any cost.

The challenge of IS as a state-building and a migration/settler project

The third challenge posed by the IS phenomenon in and beyond the Middle East, including to Russia and Eurasia, while not yet fully developed, is seriously underestimated. While the primary focus on violent aspects and manifestations of the IS phenomenon is understandable, its other far-reaching implications should not be neglected. Compared to the IS military successes, its administrative and state-building “achievements” to date appear modest, but still, they should not be overlooked. One particular aspect specific to IS as a quasi-state and an experiment in Islamist state-building, is the emphasis that its propaganda and ideology places upon turning the “Caliphate” in Iraq-Syria into a final destination and a physical, rather than imagined, “promised land” for disenchanted Muslims, including civilians, especially women and families with children. Disturbingly, it is this category of Russian citizens that dominated in the group detained by authorities at the Turkish-Syrian border that Karaulova was part of and that was allegedly heading to areas under the militants’ control. According to informal sources, women may comprise up to 15 percent of all those heading from the North Caucasus alone to areas under radical Islamist control in Syria and Iraq [12].

IS’s broader message is not just for militants to fight, but — sometimes in the form of specific “targeted calls” for certain categories of newcomers — for family members and other “right Muslims” to come and populate areas under their control (to live, work, provide administrative and technical skills, ensure logistical support for the war effort, do business, have kids). In other words, what may make IS a qualitatively new phenomenon is its potential — as yet not realized in full or even in half — to become a major ideologically-driven migration/settler movement and project in the Near East (based on a radical Islamist ideology, value and governance system).

***

Other key considerations include Moscow’s interest in preventing destabilizing transnational influences and connections not just on its own territory, but across Eurasia, in cooperation with its close CSTO allies, SCO and Asian BRICS partners .

Russia’s concern over terrorist/extremist threats to its own security is not the only impulse driving its approach to the challenge posed by IS. Other key considerations include Moscow’s interest in preventing destabilizing transnational influences and connections not just on its own territory, but across Eurasia, in cooperation with its close CSTO allies, SCO and Asian BRICS partners (which is also on the agenda of the July 2015 SCO/BRICS Ufa summits). Russia also uses the need to combat transnational violent Islamic extremism at its main current center of gravity (in the Middle East) with the goal of keeping open possibilities for cooperation and working contacts over shared security concerns with its Western counterparts, at an otherwise extremely problematic stage of Russia-West relations.

Still, Russia’s concerns about the actual and potential domestic implications of the IS challenge are a major and a very genuine driver of its approach to IS in and beyond the Middle East. This has already led Russia to introduce criminal punishment for taking part in armed groups abroad (with 250 such criminal cases in 2014 alone) [13] and to include IS in its list of terrorist organizations in February 2015 [14].

At a broader international level beyond Eurasia, Russia’s efforts have involved:

- Supporting and promoting anti-IS measures at the UN Security Council level. Russia supported the 2014 resolution (2178) [15] on foreign militants and terrorist threats to international peace and security, and initiated Resolution 2199 [16] on preventing terrorism financing from illegal oil trade in the region, unanimously adopted by the Security Council in February 2015.

- Support for states whose territory is partly occupied by IS and whose forces fight IS on the ground, in spite of all the complications and reservations intrinsic to a chronically failing post-intervention state (Iraq) and bitter and deeply divisive civil wars (both Syria and Iraq).

- Non-confrontational approach to the anti-IS coalition operation (despite serious reservations about the feasibility of a primarily military solution and disagreements with coalition members, both Western and Arab, on many other issues).

- “Positive neutrality” regarding other state and non-state-based support in the fight against IS (e.g., by regional actors ranging from Iran to the Iraqi Kurdish forces).

- Promoting the centrality of retaining basic state functionality during any transition. The latter point — Russia’s persistent aversion to uncontrolled state collapse that would create a dangerous vacuum that could be filled by exclusive sectarian forces and other extreme radicals (in Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen etc.) — has long been the centerpiece of Russia’s foreign and security policy regarding the world’s main centers of militant/terrorist activity. In fact, realizing the need to prevent the collapse of key institutions and basic state functionality, and the long-term preference for national-level, inclusive, representative arrangements rather than largely military and/or de facto sectarian solutions may be the single lowest common denominator for most stakeholders inside and outside the region, and the main starting point for the search for a way out.

ENDNOTES

1. https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/WilliamBraniff_HASCTestimony_Feb15.pdf

2. http://estepanova.net/StepanovaGTI2014.pdf

3. http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/datasets/ucdp_prio_armed_conflict_dataset/

4. http://www.visionofhumanity.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Terrorism%20Index%20

Report%202014_0.pdf5. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2012-Global-Terrorism-Index-Report.pdf

6. http://tass.ru/glavnie-novosti/679589

7. http://tass.ru/en/world/778834

8. http://www.ng.ru/ideas/2015-03-06/5_crisis.html

9. http://www.rferl.org/content/russia-tatar-jailed-for-fighting-in-syria/26751237.html

10. http://www.interfax.ru/russia/447728

11. http://tass.ru/politika/2047846

12. http://www.ng.ru/ng_politics/2015-06-02/14_islam.html

13. http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2718993

14. http://www.fsb.ru/fsb/npd/terror.htm; http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/

%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2178.pdf15. http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2178.pdf

16. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2199%20(2015)

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |