From Electorate to Caliphate

A demonstrator waves Turkey's national flag as

he sits on a monument during a protest against

Turkey's Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan and

his ruling AK Party in central Ankara

June 2, 2013

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in Political Science, research fellow at Centre for the Study of Middle East of Institute of Oriental Studies of RAS

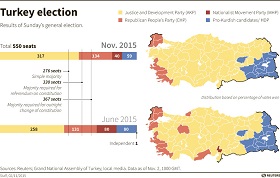

Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) won a shock victory in the country’s snap election held on November 1, 2015, receiving 49 per cent of the votes. Given the Party’s performance in the June election, where it picked up a modest 40 per cent of votes, analysts were not predicting anything special for the AKP. Party officials were equally shocked by the result. The secret to the Party’s success lies largely in the work of professional spin doctors. The stages of the AKP’s development are inextricably linked to the electoral design, election cycles and the strategies of spin. This periodization correlates somewhat with the “student, apprentice, master” paradigm used by Recep Erdoğan and his party in the run-up to the 2011 elections to describe the stages of the electoral cycle.

Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) won a shock victory in the country’s snap election held on November 1, 2015, receiving 49 per cent of the votes. Given the Party’s performance in the June election, where it picked up a modest 40 per cent of votes, analysts were not predicting anything special for the AKP. Party officials were equally shocked by the result. The secret to the Party’s success lies largely in the work of professional spin doctors. The stages of the AKP’s development are inextricably linked to the electoral design, election cycles and the strategies of spin. This periodization correlates somewhat with the “student, apprentice, master” paradigm used by Recep Erdoğan and his party in the run-up to the 2011 elections to describe the stages of the electoral cycle.

Birth and Maturation of the Party (2001–2007)

The Justice and Development Party grew out of the National Vision (Milli Görüş) Islamist movement. After the 1997 military memorandum and the outlawing of another Islamist party, the Virtue Party (Fazilet Partisi), a number of its members – so-called “rejuvenators” – banded together to form the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi).

The AKP clearly had support from the United States, the United Kingdom, Israel and other countries. In return for being gifted power and having its competitors removed from the picture, Erdoğan was supposed to help the West “reformat” the Middle East and “reformulate” Islam. Over the course of two weeks in 2001, Erdoğan visited 12 EU countries and met with President George W. Bush at the White House.

Defending the Oppressed

The AKP’s campaign strategy for the 2002 general election was built upon the idea of the Party representing the “oppressed” strata of society fighting to restore justice. Turkey needed a new centrist party, one that spoke for a significant portion of the electorate (their slogan was “We are all Turkey”), considered by the secular elite to be second-class citizens, and which promised to get rid of all types of “custodianship of the people’s will”. At campaign rallies, Erdoğan frequently repeated the slogan “Enough, it’s time to let the people to decide!”. The main 2002 campaign slogan was “Everything for Turkey” (“Herşey Türkiye için”) [1].

The secret to the Party’s success lies largely in the work of professional spin doctors. The stages of the AKP’s development are inextricably linked to the electoral design, election cycles and the strategies of spin.

The campaign was also carried out under the banner of the struggle against the “three Ys” of poverty (Yoksulluk), corruption (Yolsuzluk) and bans (Yasaklar), thus endearing the Party to the widest possible demographic. Unlike the campaign programmes of its predecessors, the AKP’s agenda was secular in nature. It was obvious that the Party was appealing to centre-right section of the electorate, to those who had voted for Adnan Menderes’ Democrat Party and Turgut Özal’s Motherland Party in the past.

The AKP ended up receiving almost 11 million votes (34.28 per cent). But an incredible piece of good fortune meant that it was able to form a single-party government, as a number of parties failed to win enough votes to pass the 10 per cent threshold to gain representation in parliament.

From 2002 to 2007, the AKP cut its political teeth in a number of ways. It took advantage of the process for becoming a member of the European Union to get the support of the Democrats and weaken its army. The most serious trial proved to be the choice of president, a task that was still carried out by parliament at the time. The Party overcame the resistance of the secularists and managed to appoint “one of its own”, Abdullah Gül. In doing so, the Party ignored the “electronic warning” of the General Staff of the Republic of Turkey on April 27, 2007, which could have resulted in a military coup. Consequently, a snap parliamentary election was held that nevertheless resulted in Abdullah Gül being appointed president. A referendum was also held, upon which it was decided that in the future the President of Turkey would be decided by a general election.

Leadership (2007–2010)

Expanding the electorate by publicizing economic achievements and mobilizing the “quagmire” – people who had voted for parties that no longer existed – was the AKP’s dominant strategy at the 2007 elections.

The AKP slogan “No Stopping, Push On! ” served as a leitmotif of the elections. A number of similar slogans were devised: “Don’t leave the country halfway through”, “It’s time for democracy!” And by preserving the main 2002 campaign slogan “Everything for Turkey”, the Party was demonstrating stability, as well as commitment to its overall vision.

You Give the Country Coal, the Internet and Women’s Organizations

The AKP departed from the norm in a number of ways during the 2007 elections. First, it brought in some 200,000 volunteers to help out with its propaganda campaign. Then women’s branches of the Party were introduced for the first time. The era of the internet was in full swing, and priority was given to developing the Party’s image on this platform, a favourite of the youth. Web sites of all the deputy candidates were set up. The Party also developed approaches for securing the vote of the economically disadvantaged, handing out coal to the poor in 2002, for example. From 2002 to 2014, the Party and companies sympathetic to the Party have handed out around $1.5 million in coal

As a result, the AKP received 46.6 per cent of the votes, 12.32 percentage points higher than in 2002. This turned out to be a surprise, not only for the AKP’s opponents, but also for the members of the Party themselves. The Party was almost shut down in 2008, but the Constitutional Court of Turkey ruled in favour of the AKP. An important step was taken on September 12, 2010, when a referendum was held on changing the “military” constitution adopted after the 1980 coup d’état.

In 2007–2010, Erdoğan cemented his sole leadership of the Party. Pluralism was eradicated methodically, while the electorate became more homogeneous. Erdoğan consolidated the centre-right, the Turkish Sunnites, by opposing them to the secularists, the Alawites and other groups, using spin tactics aimed at party’s target voters.

The “Electoral Caliphate” (2011–2013)

The PR activities of Erdoğan’s spin doctors in Arabic countries brought him fame in the Muslim East, especially among the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Syria, Qatar, Kuwait and Palestine.

The main thrust of the 2011 election campaign was on the economy. Slogans highlighting the struggle against poverty, corruption and bans were used once again. One of the more memorable moments of the advertising campaign was the series of TV commercials that carried the slogan “We dreamt and it came true!” (“Hayaldı gerçek oldu!”). The ads declared that all the achievements over the past few years were exclusively thanks to the ruling party, which was “making the dreams of the voters come true.” The economic success of recent years had laid the foundation for achieving “the goals of 2023”, for which Turkey was “ready”. In doing so, the AKP announced that it was planning to stay in power at the very least to the centenary of the formation of the Republic of Turkey.

The 2011 election campaign was probably the first in which the AKP did not present itself as a “victim”, as all the declared “enemies” of the Party had already been vanquished and new ones had yet to be found.

Long before the campaign actually began, Erdoğan traversed the country, opening various institutes and infrastructure facilities. In total, the President appeared at 90 rallies in 68 provinces. Party activists, whose numbers had grown exponentially during the AKP’s eight-and-a-half years in power, went from door to door, giving the campaign a human touch while also putting Party propaganda into the hands of every single Turkish resident. By that time, the process of consolidating the TV channels, newspapers and other media in the hands of businesspeople loyal to Erdoğan. Up to 80 per cent of TV viewers and 60 per cent of newspaper readers were under the direct influence of pro-government media. As a result, voters bought into the image created for them by the AKP, and the Party received 21,399,000 votes – almost 50 per cent of all votes cast.

The Opposition as “Polytheists”

Hasan Selim Özertem, Habibe Özdal:

What Will the Power Shift Bring to Turkish Politics

and to Turkey-Russia Relations?

The AKP’s growing feeling of invincibility was bolstered greatly by the legal proceedings brought against the terrorist organization Ergenekon and those involved in the planned secularist military coup Operation Sledgehammer (Balyoz), which resulted in the convictions of hundreds of soldiers and civilians.

The blatant cult of personality of the then Prime Minister rose to a completely new level. Many officials and journalists lost their jobs; some were even jailed for criticizing the regime. Teachers removed their personal pages from social networks, fearing persecution. Islamist rhetoric became could be heard with increasing frequency and foreign policy took a clear ideological turn towards “Muslim Nationalism” [2]. Members of the artistic community who were loyal to the regime started to call for the country to change its name from Turkey to Ottoman. Erdoğan eagerly embraced the Arab Spring, waiving the Turkish Zero Problems with our Neighbors policy. The PR activities of Erdoğan’s spin doctors in Arabic countries brought him fame in the Muslim East, especially among the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Syria, Qatar, Kuwait and Palestine.

It is unclear as to exactly what played the decisive role in Erdoğan’s decision to start calling himself the “Caliph of the Whole World” – his psychological makeup or the people with whom he has surrounded himself. Perhaps it was just a cover for the establishment of the presidential system, i.e., the regime of Erdoğan’s individual power.

Erdoğan’s supporters frequently referred to him as “the shadow of Allah on earth”, “the man who has absorbed all the attributes of God, “the eternal leader”, etc. Demonstrating alternative views or supporting different political parties were condemned as shirk (polytheism) [3].

The AKP has worked hard to get the representatives of Turkey’s Muslim communities (6.2. per cent of the country to “swear an oath of allegiance” to the Party). Focus was placed on convincing the leaders of these communities to work together with the government, as well as on offering financial incentives. Far from all the leaders swore allegiance, however, with supporters of Fethullah Gülen, a core group of Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan’s students, a section of the İsmail Ağa Jamia refusing to give their unconditional support to Erdoğan.

The Fall of the Caliphate (2013–present day)

As per tradition, the Party once again found an external culprit. The government, which was the victim in the whole affair, discovered a plot against them.

The regime’s first “wobble” came in summer 2013 during protests staged at Istanbul’s Gezi Park. The environmentalist protest, which was put down rather aggressively by police, turned into large-scale civil unrest across the country. The park and nearby Taksim Square became symbols of resistance, primarily among left-wing forces. The protesters were particularly negative in their assessment of the Prime Minister, who in turn did not hide his contempt for them. Erdoğan announced that he was having “trouble keeping the half at home,” referring to the percentage of votes his party had won at the election.

The government claimed that the protests were the work of external enemies, the “bond interest lobby” and opponents of the “new and strong Turkey.” Society became polarized as a result of these processes, although support for the Party did not wane in terms of percentage points, with Erdoğan “cementing” his electorate through pro-Islamic rhetoric.

How to Take Money out of the Country

The real shock for the AKP came on December 17 and 25, 2013, when the Prosecutor’s Office and the Police detained dozens of people, including the sons of three ministers, on corruption charges. Those involved were accused of taking bribes and awarding contracts and government-owned land illegally. The response of Erdoğan’s government confirmed the seriousness of the allegations: practically all of the public prosecutors and police officers involved in the case were removed and transferred to less prominent positions. More than 100,000 people have been removed from their posts in 2014–2015. Three ministers resigned and seven other members of the Cabinet were replaced. The AKP blocked the investigation into the actions of ministers in the Supreme Court. The whole affair was essentially swept under the carpet, although hundreds of pieces of evidence collected as part of the investigation eventually turned up on the internet. The most famous of these was the recording of a telephone conversation between Recep Erdoğan and his son Bilal on December 17, 2013, during which the President ordered his offspring to get rid of all the cash he had stored at home immediately.

And the Ravens Ridiculed

Ilshat Saetov:

Turkey Politics: Who Wins from Stirring the War

against Kurds?

As per tradition, the Party once again found an external culprit. The government, which was the victim in the whole affair, discovered a plot against them. And the obedient media repeated the details. It was, of course, the usual suspects – the secularists, the military, the freemasons, Israel and the United States, with one addition, namely, Hizmet and its leader Fethullah Gülen. The prosecutors, judges and police officers involved in the case were declared members of a “parallel government”, a “Jamia” who had betrayed their motherland. Only a year before, Erdoğan had made an inspired speech an inspired speech at the closing of the Turkish language contest, organized by members of the Gülen movement. His Deputy, Hüseyin Çelik, joked that “Only ravens laugh at the fact that Jamia has penetrated everywhere.” However, following the events of December 17, 2013, the government-controlled media started to accuse Gülen and his supporters of all kinds of unspeakable things. It should be noted that these accusations were nothing new, as Gülen had been tried and acquitted by the court in 2006 on charges brought by the Prosecutor’s Office for lack of evidence.

The struggle against “Jamia” was not just a method of spin to help change the political agenda, it was the central line of Recep Erdoğan’s pre-election campaign in 2014–2015.

They Might Steal, but They Do a Good Job as Well

The campaigns before the municipal elections in March and the Presidential elections in August 2014 were carried out under the slogan “A new war of independence” against the “parallel government”. It was announced that, if the AKP secured a great number of votes, it would mean that the Party had been “whitewashed” of all corruption charges. The AKP and Recep Erdoğan received 43.4 per cent (19,470,000) and 51.2 per cent (20,844,000) of the votes, respectively. The results of the presidential election can also be ascribed to the passivity of those voting for the opposition, which were short by a few million.

Most voters (70 per cent), including Muslims, were aware of the large-scale corruption, but their attitude towards the government could be described as “well, they might steal, but they do a good job as well” («çalıyor ama çalışıyor»).

Winning just over 40 per cent of the votes, the AKP was unable to form a majority in parliament. This was largely due to the fact that the Kurdish party passed the 10 per cent threshold to gain representation in parliament for the first time in Turkey’s history.

The atmosphere of hate in the country escalated. Clashes between youth groups on ideological grounds were reported. Human rights violations increased. Journalists were persecuted. Censorship grew, and pressure on all segments of society intensified.

Chauffeurs, relatives of those in power and journalists sympathetic to the government became candidate deputies during the elections.

At the same time, many of the founding fathers of the AKP, including former President Abdullah Gül and former Speaker of the Grand National Assembly Bülent Arınç, remained on the side-lines of party politics.

Vote to Live

The AKP experienced a rude awakening on June 7, 2015. Its election campaign was uninspiring; the Party’s leaders were content to harp on about their successes for the hundredth time and accuse the “parallel government” of trying to carry out a coup d’état, insisting upon a presidential system that is unpopular with the people. For the first time, the Party went to the polls under the leadership of Ahmet Davutoğlu. Winning just over 40 per cent of the votes, the AKP was unable to form a majority in parliament. This was largely due to the fact that the Kurdish party passed the 10 per cent threshold to gain representation in parliament for the first time in Turkey’s history. This seemingly put an end to Erdoğan’s dreams of a super-presidential republic. The “electoral Caliphate” looked like it was going to fall for good.

The President of Turkey was more than displeased with the election results and he did everything in his power to make sure that snap elections took place. The AKP incited internal conflict before embarking on another full-scale war with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. A number of terrorist attacks were carried out. Armed clashes took place. A series of explosions in Ankara on October 10, 2015 resulted in the deaths of over 100 people. The AKP’s discourse can be summed up in a single phrase spoken by Islamic University of Rotterdam Rector Ahmet Akgündüz: “If you want the bloodshed to stop, vote for the ruling party”. The AKP also used such slogans in its pre-election campaign as “There is no you, there is no me, there is Turkey,” thus scaring the entire electorate into voting: the religious Kurds, nationalists, Islamists and doubters. As a result, the AKP regained its majority in parliament, winning a record 23 million votes (almost 50 per cent).

The Bond of Fear

The ruling party will continue to build its regime, aligning government agencies with the party structure and concentrating power in the hands of one person.

The events in Turkey are somewhat reminiscent of the Young Turks’ campaign of 1912. Following elections that were held in an atmosphere of intimidation and terror, the Young Turks won 269 of the 275 seats and proceeded to eliminate the opposition. Within two years, they had dragged the Ottoman Empire into the First World War, bringing the country to its knees.

The terrorist attacks will probably stop now. But the AKP is unlikely to change its policy on all other fronts. Recep Erdoğan is clearly thinking about the presidential system once again – reports of a possible referendum appeared only a few days after the election. The ruling party will continue to build its regime, aligning government agencies with the party structure and concentrating power in the hands of one person. Any and all forms of opposition will be silenced. The words of the victorious Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu that everyone should “live together in harmony” most likely do not apply to those who are not loyal to the Party.

It is difficult to say just when the “electoral Caliphate” will outlive its usefulness. Maybe the AKP has got a second wind following the November 1 elections. But it seems that all the processes taking place in the country point against the party in power. AKP voters, even if they represent just less than half of the electorate, are not united by a clear ideology or constructive agenda. They are united by fear of terrorism, civil war and the arrival of the mythical Kemalists. This is hardly a basis for the future development of the country. The potential for new Gezi protests is far greater than in 2013.

1. Compare with the slogan of the Nazi storm troopers “Deutschland über alles.”

2. White J. Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks. Princeton University Press, 2014.

3. In Islam the word shirk means to ascribe partners to Allah, use intermediaries to appeal to God, and paganism.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |