The TAPI project: Turkmenistan’s bet in pipeline geopolitics

Dowletabat / Sarakhs Compressor station, 2011

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 2) |

(1 vote) |

Independent Expert

Slowly but surely, steps are being taken to actually start the construction of the TAPI pipeline. But what exactly is the motivation of the four countries (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India) to take part in this project, and what are the main challenges they are facing? Who is supporting the project and what factors are pushing neutral and closed Turkmenistan to reach outside of its borders? Finally, what are the project’s current prospects?

‘This major project is an economic priority, not only for the energy supplier, but also for transit countries and consumers. It will give powerful impetus to strengthen sustainable development and peace.’

President of Turkmenistan

Slowly but surely, steps are being taken to actually start the construction of the TAPI pipeline. But what exactly is the motivation of the four countries (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India) to take part in this project, and what are the main challenges they are facing? Who is supporting the project and what factors are pushing neutral and closed Turkmenistan to reach outside of its borders? Finally, what are the project’s current prospects?

As one of the world’s top ten gas producers, Turkmenistan has the fourth largest gas reserves in the world and, consequently, has yet to fulfill its export potential in this sphere. Yet to fulfill this potential by primarily exporting to neighboring Central Asian nations is hardly an option. Located in an energy-rich region, be it Uzbekistan with its gas reserves, Kazakhstan with oil, or Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan with hydro-energy, the country needs to look further abroad to realize its ambitions of becoming a major gas exporter, which will enable it to gain greater economic stability and a geopolitical leverage.

Thus, diversification of export routes and exporting partners is key. Russia has traditionally been the main buyer of Turkmen gas, although supplies traveling to and through Russia gradually fell over the 2000s. China has taken over actively, becoming the main investor in Turkmenistan’s gas infrastructure and gas field development since then, which has led to a quasi-monopoly of Chinese firms over the country’s resource extraction and export routes, and a risky over-reliance on a sole consumer. Aware of this fact, for the past twenty years Turkmenistan has been making a number of more or less successful attempts to diversify its supply routes, for example, through the Trans-Caspian pipeline.

An undeniable highlight of the past year has been the December 2015 launch of the Turkmenistan Afghanistan Pakistan India pipeline project, also known as TAPI. A highly ambitious initiative with its roots going back to the former President of Turkmenistan, the gas pipeline project has been positioned as a pipeline for peace, a means of connecting Afghanistan with the region, and also as a bridge between India and Pakistan. Furthermore, the project has a primary significance for Turkmenistan itself, both internally and externally. According to the Director General of the Asian Development Bank’s Central and West Asia Department, Sean O’Sullivan, ‘This groundbreaking marks a new chapter in regional economic cooperation…The TAPI pipeline is a true game changer, a historic undertaking that will address the energy needs of the region and contribute to development, peace, security and in turn prosperity’.

TAPI: the 20-year long genesis

The original project started on March 15, 1995, when a memorandum of understanding between the governments of Turkmenistan and Pakistan for a pipeline project was signed, promoted by the Argentinian company Bridas Corporation, the US Unocal and the Saudi Delta. An opening ceremony took place in 1997, and an informal agreement with the Taliban, ruling over larger parts of Afghanistan at the time, was reached. However, the 1998 attacks on the US embassies, allegedly planned by Osama bin Laden, resulted in the American Unocal withdrawing from the project.

Five years later, in December 2002, talks were resumed between Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Increasing instability in southern Afghanistan from de facto Taliban control made the feasibility of the pipeline questionable and the project stalled once more only to resume in 2008, when Afghanistan, Pakistan and India signed a framework agreement to buy natural gas from Turkmenistan. This intergovernmental agreement, also known as the Ashgabat Interstate Agreement, signed in Ashgabat on December 11, 2010, is currently the main document for the TAPI project. In May 2011, the Afghan parliament approved the agreement on the gas pipeline, which is notable given the United States is supportive of the pipeline project, bypassing both the Russian route and concurring with the Iran-Pakistan pipeline. In April 2012, disagreements between India and Afghanistan, and India and Pakistan on transit fees, slowed down the process again.

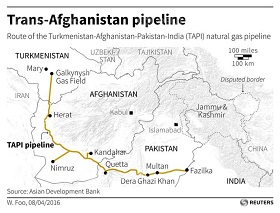

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Natural Gas pipeline (TAPI) is planned to be 1,814 km long, with 214 km running through Turkmenistan from Galkynysh — the gas field in Mary province estimated to be the second largest in the world— to Fazilka, in the Indian state of Punjab, 774 km running through the Afghan provinces of Herat, Farah, Helmand, Nimroz and Kandahar, and with 826 km through the Pakistani provinces of Baluchistan (Quetta, reputed home of the Taliban’s ruling council) and Punjab (Dera Ghazi Khan and Multan). The pipeline is expected to carry 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually for a duration of thirty years. Pakistan and India will receive over 36.8 million cubic meters of gas daily (42 per cent of the share), while Afghanistan is set to receive 14.1 million cubic meters daily (16 per cent of the share). The $10-billion project is slated for completion in 2019.

Recent positive developments

On August 6, 2015, at its 22nd meeting, the TAPI Steering Committee endorsed the State Concern ‘Turkmengaz’ as the leader of the Consortium TAPI Pipeline Company Limited. The groundbreaking ceremony for TAPI, marking the beginning of the work on the pipeline, was held on December 13, 2015 close to the southeastern city of Mary, hosted by President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, and in the presence of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Indian Vice-President Muhammad Hamid Ansari.

On April 7, 2016, the shareholders of the TAPI Pipeline Company Limited (TPCL) — 85% owned by Turkmengaz, 5% by state-owned Afghan Gas Enterprise, 5% by private Pakistan Inter State Gas Systems Limited, and 5% by state-owned India Gail Limited company— signed an Investment Agreement in the presence of petroleum ministers and senior government officials of the four countries and the Asian Development Bank. The Agreement provides an initial budget of over $200 million to fund the next phase of the project, which includes funding for detailed engineering and route surveys, environmental and social safeguard studies, and procurement and financing activities, all to enable a final investment decision, after which construction can begin.

Acting as the TAPI secretariat since 2003 and as the transactions advisor since November 2013, the Asian Development Bank has provided a long-term essential support to the project. Among others, the ADB helped establish the Consortium TPCL, select Turkmengaz as consortium leader, and finalize the Shareholders and Investment Agreements. According to ADB’s Director General Sean O’Sullivan, ‘TAPI exemplifies ADB’s key role in promoting regional cooperation and integration over the past 20 years. It will unlock economic opportunities, transform infrastructure, diversify the energy market for Turkmenistan, and enhance energy security for the region’.

Rationales behind the Project

The Turkmen rationale

Workers hold Chinese and Turkmenistan state

flags as they attend a launching ceremony at

Galkynysh gas field in eastern Turkmenistan

September 4, 2013

According to the World Bank Chief Economist for Europe and Central Asia Hans Timmer, ‘The fall of energy prices and the depreciation of the manat have opened a window of opportunity for Turkmenistan to become more internationally competitive. To seize this opportunity, integration into the multilateral trading system is important’. In other words, Turkmenistan needs the success of this pipeline project. Indeed, if you look at the latest economic data available for the country published by the International Monetary Fund, ‘The economic shocks are expected to lead to a decline in GDP growth from 10 per cent in 2014 to about 7 per cent in 2015 and 6 per cent in 2016, due to flat natural gas and oil production as well as reduced budgetary investment. As a result of lower revenues from hydrocarbon exports, the external current account as well as fiscal balances are expected to weaken’. In an economic system where the hydrocarbon sector continues to account for 35 per cent of GDP, 90 per cent of exports, and 80 per cent of fiscal revenues, long-term decline in revenues is a very risky option.

Turkmenistan is facing a crisis in exporting its hydrocarbon resources. This is one of the main reasons why President Berdimuhamedov is so eager to launch the TAPI project. Gas trade with Russia gradually decreased from 42.3 bcm in 2008 to 4 bcm in 2015. Gazprom from 2016 on will no longer import Turkmen gas. Four different circumstances contributed to this trend: the gas dispute in 2009 after a pipeline connecting Turkmenistan to Russia was damaged that led to a 25 per cent GDP loss for Turkmenistan; the opening of the Central Asia — China gas pipeline at the end of 2009, drastically changing Turkmen priorities; the announcement by Gazprom that Turkmen gas is unprofitable for Russia; and finally, the recession in Russia for 2015 estimated at 3.7 per cent because of international sanctions and the fall of hydrocarbon products prices.

Gas trade with Iran displays a similarly bleak outlook. Quantitatively, the gas volumes traded were never as significant as those that Turkmenistan exchanged with Russia or China: in 2006-2013, Iran’s total purchases of Turkmen gas did not exceed 56.47 bcm. In 2013, Tehran requested that the purchase of Turkmen gas was to proceed to gas-goods swaps. Ashgabat’s systematic refusal questioned the very foundations of its energy linkages with Tehran. In August 2014, Iranian officials announced the potential suspension of any gas trade with Turkmenistan, stating that a planned increase of domestic production would make imports unnecessary from 2017 onwards. The drastic tones of this declaration were nevertheless diluted by a deal signed in November 2014, in which Iran committed to continue buying Turkmen gas and Tehran still bought 6.5 bcm from Ashgabat in 2014. However, the trend is definitely negative [1].

China is now the main buyer of Turkmen gas, replacing Russia’s role. Between 2009 and 2013, bilateral gas trade grew by 800 per cent, reaching 25.9 bcm in 2014, less than the 30 bcm agreed upon by state-owned Turkmengaz and China National Petroleum Corporation. In the first three months of 2016 alone, Turkmenistan supplied China with 10.6 bcm of gas, a 33 per cent increase over the same period in 2015. In 2015, Turkmengaz accounted for over 81 per cent of all gas exports to China by pipeline, BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy shows. On the other side, 35.8 per cent of the natural gas imported by China originated from Turkmenistan.

In other words, the TAPI project is essential for Ashgabat to avoid dependence and reliance on Beijing, after having depended on Moscow for decades. Diversifying its partners is therefore a priority for Turkmenistan.

Diversification of the country’s economic structures is simply not an option for a regime that thrives on monopolistic control of gas revenues; the only alternative to dependency on China would be a further diversification of Turkmenistan’s export routes. The expansion of gas linkages with South Asia, to be accomplished through the operationalization of the TAPI natural gas pipeline, does, however, represent a very challenging undertaking. Huge financial costs are not the only hurdle to the project’s full implementation, as major security concerns and failure to identify a commercial champion appear to prevent TAPI development [2].

The Afghan hope

Apart from getting access to a gas pipeline, Afghanistan will benefit from transit revenues and job creation in maintenance and securing the pipeline. Although Afghanistan is rapidly approaching an energy crisis as deforestation creates a supply shortage, it is not a major consumer and will receive only 5 bcm annually. Less than a third of the Afghan population is connected to the electricity grid, and up to 85 per cent of total primary energy consumption comes from biomass fuels: at the household level, firewood alone comprises 65 per cent of total consumption. Thus, the government has made non-biomass supply options, such as natural gas, a priority in its efforts to improve energy access throughout the country. According to Rafiullah Nazari, director of the Afghanistan Regional Studies Center, the pipeline could make Afghanistan earn as much as $400 million in annual transit fees. “Once completed, the TAPI pipeline will provide a sustainable source of energy for Afghanistan, help catalyze investment and create local job opportunities,” said Mir Ahmed Jawid Sadat, Afghanistan’s Deputy Minister of Mines and Petroleum. “Critically it also provides a mechanism for renewing partnerships with our ‘Silk Road’ neighbors, and shows the desire of the region for peace, stability and security through economic development”, he concluded.

TAPI is also seen as an opportunity to pave the way for restoring political and social stability and peace in Afghanistan. It could contribute to the rehabilitation of the war-torn country.

Peace pipeline: Pakistan - India connection

Berdymukhamedov shakes hands with Afghan

President Ashraf Ghani, Pakistani Prime

Minister Mohammad Nawaz Sharif, and Indian

Vice President Hamid Ansari during a ceremony

in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. The three leaders

have joined the president of Turkmenistan in

breaking ground on a new pipeline intended to

deliver natural gas from the energy-rich former

Soviet republic to their three countries.

Pakistan and India are looking for ways to acquire low-cost energy for domestic consumers and local industry with their increasingly large and prosperous populations. Pakistan needs energy supplies as it is periodically subject to energy shortages. It needs to meet a 6 per cent annual supply growth so as to meet projected demand for 2020 — 50 bcm, an increase largely attributed to demand for compressed natural gas in the automobile sector. India is in a similar situation, expecting 6.8 per cent annual growth until 2021, when it is expected to reach more than 180 bcm, and hopes to extract from Turkmenistan between 15 to 25 per cent of its natural gas needs. After years of increasing its production at the Galkynysh natural gas field and improving the connectivity of its domestic distribution network, Turkmenistan is well poised to ramp up production to meet growing Indian and Pakistani demand. Another factor that has to be taken into account is the long-standing unstable bilateral relations between Pakistan and India.

The spoilers Security concerns

In order to reach Pakistan and India, the pipeline must pass through war-torn Afghanistan, which is still dealing with a years-long Taliban insurgency and the recent appearance in the region of the Daesh terrorist group, on top of the turbulent Baluchistan province in Pakistan.

In December 2015, Afghan president Ashraf Ghani pledged a 7,000-strong force to guard the pipeline and its construction, specially noting the setup of a special military unit. The pledge was confirmed by Daud Shah Saba, Afghan Minister of Mines and Petroleum, who mentioned that security forces have already succeeded in securing the biggest mining field of the country. However, members of Helmand provincial council said that the volatile situation in the province could pose a major threat to the implementation of TAPI.

Pakistani Defense Minister Khwaja Asif said that his country would use all its influence with the Taliban to ensure the pipeline’s security, a declaration criticized by the Afghan government, which said that it contravened earlier pledges by Pakistan to not interfere in Afghanistan’s internal affairs.

Muhammad Hamid Ansari, Indian Vice-President, declared: ‘We have to be aware of the challenges awaiting us. We cannot anymore let violence and perturbations threaten the quest for the economic development and the security of our population’. According to the Pakistani newspaper The Nation in March 2016, ‘The process of removal of mines in Afghanistan from the TAPI gas pipeline route has begun with the help of Afghan security forces’.

Typically, projects that bring value into a country face less opposition than those seeking to exploit resources for export, so the local Taliban elements will likely tolerate the project as long as their strategic interests are not threatened. Indeed, TAPI is unlikely to attract the ire of local tribal leaders unless it partners with Western investors. Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahed said that foreign companies wishing to invest in mines — those which can be applicable to the pipeline project — must first get permission from a Taliban commission to avoid becoming targets: “The commission will review and scan the companies to know whether the foreign companies didn’t come for spying or something that will hurt our people and us".

According to Michael Kugelman: ‘The TAPI countries are keen to see the project to come true, but the current situation makes it unlikely. It is hard to imagine the construction of the pipeline through Afghanistan due to security issues. Many parts of Afghanistan have become completely inaccessible. Thus, it is not wise to invest capital, labor and machinery for an extended period of time,’ he added. However, the current situation of the security in Afghanistan makes the construction of the pipeline improbable.’

Funding the pipeline project

Turkmengaz is the consortium leader. However, the project remains open to foreign companies interested, and the offer has been repeatedly put forward by Turkmengaz Vice-President Muhammetmirat Amanov. UAE-based Dragon Oil manifested its interest without confirming it. Dragon Oil already operates off Turkmen coasts at the Cheleken gas field. The Turkmen President has also asked for support from the Islamic Development Bank, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Because of Afghanistan's limited financial resources, it must raise 3 per cent of its own financing (about $300 million) before the Asian Development Bank will provide the rest. If it cannot raise the funds, the Afghan government will forfeit its stake in the project, which may cause delays as investors search for another stakeholder. Similar restrictions have not been placed on Pakistan or India.

Despite the restrictions on funding, the consortium of Turkmengaz, Afghan Gas Transit, Pakistani Inter State Gas Systems and Indian GAIL needs to raise about 30 per cent of the $10 billion in order to begin construction. The favorable economic status of the project, as well as Turkmengaz's proactive commitments, indicate it is capable of securing financing for the remainder of its stake. Even so, the firm may seek foreign partners to help fund the remaining 70 per cent of the project. Although Turkmenistan may seek to attract foreign partners, the likelihood that it will offer up an equity stake in the natural gas source field will depend on how in need it is for financing and how much the cost will be. The Islamic Development Bank has announced its interest in providing financial backing for Turkmengaz, while Pakistan claims China may help finance its portion through its $46 billion investment project, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Conclusion, or lessons from the past

The feasibility of the project was compromised in the 1990s for various reasons, primarily the fact that total Turkmen gas reserves were not believed to be able to reach the 20 bcm annually [3]. Secondly, India and Pakistan’s needs in natural gas were questioned.

Two decades later, these concerns have vanished. Turkmenistan’s total gas reserves are believed to constitute the fourth largest in the world — after Russia, Iran and Qatar, and in 2014, the total production reached 69.3 bcm. Turkmenistan’s export potential is rapidly expanding, and will be boosted with new gas fields recently discovered in the Mary and Balkan velayats. In October 2015, Turkmengaz reached an agreement with Japanese firms Mitsubishi, Chiyoda, Sojitz, Itochu and JGC to boost overall production at Galkynysh to 95 bcm by 2018 for the TAPI pipeline. Internal structural demand of Pakistan and India for natural gas is also exponentially increasing as both countries are considered emerging and economically developing.

Even as both of these concerns have disappeared, the security situation in Afghanistan and some areas of Pakistan still poses a great threat to the project. Despite official pledges of pipeline securitization by Afghan special forces, there is no certainty that Afghanistan will be able to actually secure the whole leg of the pipeline. On top of that, there has been no cross-checked information of any actual construction of the pipeline on Turkmen territory since the inaugural ceremony of December 2015.

Finally, time is a rival for the project. In April 2015, Pakistan signed a huge infrastructure deal worth of $46 billion with China, which also includes financing the construction of the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline. Pakistan’s incentive to construct its section of the TAPI pipeline is thus no longer as strong as it was before. The next year, during which the Turkmen section is to be completed and the section in Afghanistan begun, will thus be a critical period, in which the project will either take off or prove to be unfeasible to international partners.

1. Luca Anceschi. CAP Policy Paper Turkmenistan’s Export Crisis: Is TAPI the answer? http://centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Policy-Brief-27-June-2015.pdf 2015.

2. Ibid

3. Turkmenistan: Strategies of Power, Dilemmas of Development, Sebastien Peyrouse, Routledge, 12.02.2015

(votes: 1, rating: 2) |

(1 vote) |