Remnants of Bretton Woods or a New Brick in its Foundation?

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D. in History

Many observers see the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Reserve Currency Pool as a BRICS-led challenge to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, while the emergence of new financial stabilization mechanisms and development institutions appears to augment and strengthen rather than threaten the existing monetary and credit system.

Many observers see the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Reserve Currency Pool as a BRICS-led challenge to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, while the emergence of new financial stabilization mechanisms and development institutions appears to augment and strengthen rather than threaten the existing monetary and credit system.

The most prominent event of the 7th BRICS summit took place a day before the actual event itself and 1,500 kilometers from its venue in Ufa. In fact, it happened on July 7 in Moscow, where an agreement was signed to launch the Reserve Currency Pool, as the NDB Board of Directors held its maiden session.[1] International media and some officials in the BRICS and beyond have frequently referred to the newly created institutions as an alternative to the international bodies that form the core of the modern economic order set up in 1944 at the Bretton Woods conference. Is the BRICS enough muscular to revise the existing economic system by establishing a competitive alternative to the IMF and the World Bank as well as by offering a new monetary system that better reflects the global balance of forces?

The BRICS New Financial Lever at Work

The NDB was established to mobilize resources for infrastructural projects across the world.

The NDB was established to mobilize resources for infrastructural projects across the world, participating through credits, partnerships and other financial instruments. Initially, its starting capital was USD 50 billion, equally distributed between the member countries. The Board is formed via compromise, with Board seats equally distributed between the member states and the presidency rotated every five years. The bank will be headquartered in Shanghai and have its first regional office in South Africa.[2]

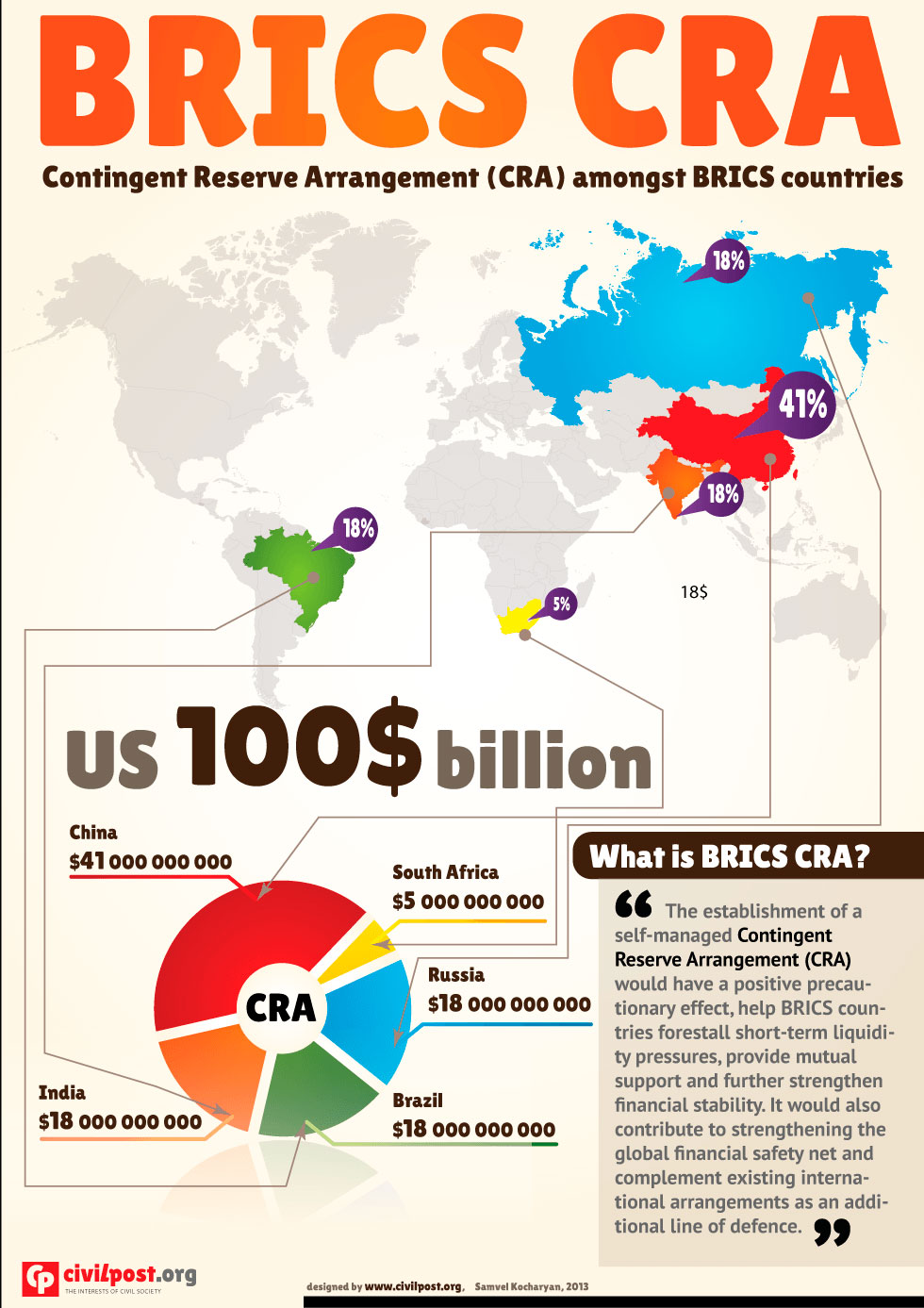

The Reserve Currency Pool is a mechanism of mutual financial support, whereby the central banks of the member countries undertake to provide funds in U.S. dollars if liquidity problems arise. The total sum will reach USD 100 billion, with USD 41 billion extended by China, USD 18 billion by Russia, India and Brazil, and USD 5 billion by RSA.[3] The mechanism is meant to help BRICS countries alleviate external payments deficits and their consequences, as well as prop up their national currencies, serving as an alternative to the IMF. The undertaking parties may apply for financial aid within the Pool limits. If the request is approved by a simple majority, the funds will be allocated as a currency swap, with the applicant buying U.S. dollars from other participants for its national currency and undertaking to buy out the sum in future at an agreed-upon exchange rate. The distribution of the aid provided will be proportional to the participants’ contribution to the Pool.[4]

Is There Any Difference from Existing Institutions?

Even a superficial description of the BRICS financial institutions shows that the Pool and the NDB duplicate the functions of the IMF and the World Bank. The new financial establishments have emerged as a response by the BRICS to the unfair economic order, but the BRICS does not intend to revise its fundamentals, willing to set up similar bodies de facto based on the misbalances inherent to the IMF and the World Bank.

The main grudge of the BRICS boils down to its insufficient influence on decision taking that fails to reflect the practical input of its members to the global economy. In late 2014, the BRICS states accounted for 21.82 percent of the world’s production,[5] while their aggregate share in the IMF vote made up only 11 percent, i.e. less than that of the United States, which controls 16.7 percent of the vote.[6] However, the situation will not change any time soon, and the IMF will remain dominated by the industrialized countries, because the current formula of calculating votes places the share of economy at only 50 percent, while other components include the amount of reserves and more subjective parameters like openness and volatility. This method effectively prevents the BRICS countries from building up their clout in the IMF despite their economic successes.

At the same time, the real size of economies have not been reflected in the BRICS institutions either. The equal participation of the NDB founders is a result of political consensus because India objected to the obvious tilt in favor of China which was initially offered a much larger share of the authorized capital. Moreover, the NDB agreement envisages artificial limitations intended to solidify the main role in decision-taking in the hands of the founders if more shareholders enter. The share of BRICS countries in the bank capital should not drop under 55 percent, while the share of each new shareholder cannot exceed 7 percent.[7]

BRICS does not intend to revise its fundamentals, willing to set up similar bodies de facto based on the misbalances inherent to the IMF and the World Bank.

At first glance, the obligations within the Reserve Currency Pool match the sizes of member-countries' economies, although the misbalance in borrowing rights is obvious. The borrowing ceilings are determined individually for each country by multiplying the size of commitments by a certain coefficient – 0.5 for China and 2 for the RSA.[8] Hence, Beijing is acquiring the role of the key creditor, and South Africa and future members becoming borrowers.

Developing countries also tend to mistrust the monetary and credit institutions because in most cases, their assistance is conditional. Borrowers are made to follow IMF prescriptions that frequently require fundamental economic reforms. This practice has proven its weakness many times, as reform projects have been standard for countries differing significantly in their economic potential. As a result, cooperation with the IMF sometimes has caused social unrest and regime change, as was the case in 1998 with the Suharto government in Indonesia.

Working individually, Russia, India and China are more flexible in extending preferential credits and development assistance, avoiding interference in the domestic affairs of borrower countries. The only formal criteria for allocating funds from the Reserve Currency Pool are the absence of outstanding debt and the threat of pressure on balance of payments.

However, receiving financial aid may become complicated, since decisions can be based on the political will of the BRICS members. The Pool moneys are kept on the accounts of their own central banks, which cannot make decisions on financing foreign states without consent from their governments.

Working individually, Russia, India and China are more flexible in extending preferential credits and development assistance, avoiding interference in the domestic affairs of borrower countries.

The main difference of the BRICS institutions from the IMF and World Bank seems to lie in the global economic clout rather than in greater fairness. Although the BRICS bodies are open to new members, the governing structure does not make global coverage possible. Moreover, the IMF can also act internationally as a negotiating party vis-à-vis national governments, whereas the BRICS Pool is only a mutual assistance mechanism deprived of this independent actor role.

A New Bank, a New Trend

Kazushige Kobayashi, Manuel A.J. Teehankee:

The AIIB’s Launch Sets the Stage

for Supply-Side Competition in

Development Finance

The very emergence of the BRICS financial institutions will barely undercut the Bretton Woods system. After Ufa, the BRICS will try to accumulate USD 100 billion in the Pool and USD 50 billion in NDB authorized capital, which is noticeably inferior to the IMF (USD 327 billion)[9] and the World Bank (USD 223.2 billion).[10] But if regarded as part of the continuing trend since the 1970s toward the fragmentation of the global financial system, the establishment of the BRICS institutions might appear somewhat menacing to their positions.

The BRICS countries were hardly the first victims of inefficient international monetary and credit organizations. In 1970, Latin Americans set up the CAF-Development Bank of Latin America for financing infrastructure projects with no help from the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, its regional counterpart. Although less affluent than the Bretton Woods competitors, the CAF leads the way in financing the Latin American projects.[11] Since no help came from the IMF during the 1997 financial crisis, the Asian countries launched the Chiang Mai Initiative – the system of bilateral currency swaps uniting ASEAN, China, Japan and South Korea in order to prevent national currency swings.[12] In 2013, Beijing set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as an alternative to the Asian Development Bank for financing infrastructure projects in Asia, among other things, the construction of the transportation component for the New Silk Road.

In the long term, these trends may as well deprive the Bretton Woods institutions of a monopoly for the title of the lender of last resort. Even now, the IMF serves mostly Western countries, with 45 percent of credit lines going to Europe – Greece, Ukraine, Romania, Poland and the Balkans,[13] while the Latin Americans, Africans and Asians tend to prefer seeking intra-regional or South-South sources in order to evade the burdensome commitments imposed by the IMF and the World Bank.

There are Never Too Many Banks

It seems premature to suggest that the BRICS countries are undermining the fundamentals of the economic world order, as they undeniably are part and parcel of it. Quite the contrary, they are trying to expand their role and take on additional obligations toward maintaining its stability. The participation of the BRICS states in regional monetary and credit organizations does not rule out their quest for greater influence in the IMF and the World Bank. Competition between old and new institutions does not mean the complete replacement of the Bretton Woods system with new mechanisms for stabilizing the global economy.

In fact, the monetary and crediting mechanisms of the BRICS use the same principles as the IMF and the World Bank, differing only in available funds, representation and financing terms. It seems hardly an overstatement to claim that the emerging institutions augment and bolster rather than damage the Bretton Woods arrangements, which frequently fail to assist development in many regions of the world. Far from every country can afford their costly decisions. Hence, many regard the IMF and the World Bank with suspicion, to a great extent due to their poor performance during previous crises. Therefore, the BRICS Pool and NDB should attract many developing countries which are unwilling to pay extra and risk financial and social stability in exchange for handling short-term economic problems. At the same time, there will always be countries eager to go beyond preferential lending and carry out structural reforms with technical help from the IMF and the World Bank. As a result, the BRICS institutions may fill a niche in the global monetary and credit system gradually vacated by the established actors.

[1] - RBK, USD 200 billion vs. USD 2 trillion: will BRICS form an alternative to the IMF? July 7, 2015// http://top.rbc.ru/finances/08/07/2015/559d33369a7947d227dba889

[2] - Agreement on the New Development Bank, June, 2014// VI BRICS Summit // http://brics6.itamaraty.gov.br/agreements

[3] - Central Banks of BRICS Sign Operational Agreement for Reserve Currency Pool. Press Release of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation (Bank of Russia), July 7 2015// http://www.cbr.ru/press/pr.aspx?file=07072015_162910if2015-07-07T16_10_14.htm

[4] - Treaty For The Establishment of a BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, Melbourne, 21 June, 2014// VI BRICS Summit // http://brics6.itamaraty.gov.br/agreements

[5] - World Bank, World Data Bank, Global Development Indications// http://databank.worldbank.org/data//reports.aspx?source=2&country=&series=NY.GDP.MKTP.CD&period=

[6] - IMF, Quota and Voting Shares Before and After Implementation of Reforms Agreed in 2008 and 2010// http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2011/pdfs/quota_tbl.pdf

[7] - Article 8 – Subscriptions of Shares, Agreement on the New Development Bank, June, 2014// VI BRICS Summit // http://brics6.itamaraty.gov.br/agreements

[8] - Article 5, Access Limits and Multipliers, Treaty For The Establishment of a BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, Melbourne, 21 June, 2014// VI BRICS Summit // http://brics6.itamaraty.gov.br/agreements

[9] - IMF at Glance, Fast Facts// http://www.imf.org/external/about.htm

[10] - The World Bank Treasury, Everything you always want to know about the World Bank // http://treasury.worldbank.org/cmd/pdf/WorldBankFacts.pdf

[11] - Financial Times, CAF: The Future Looks Bright for LatAm, 06 Feb, 2012// http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2012/02/06/caf-a-bright-future-for-latam/?Authorised=false#axzz1qwCG5bFa

[12] - E.Arapova, A.Baikov. Regional Initiatives of Financial Cooperation in Asia-Pacific // International Processes, 2012, Volume 10, №3, pp. 98-107 // http://www.intertrends.ru/thirtieth/Arapova.pdf

[13] - IMF, IMF Lending Arrangements as of June 30, 2015// http://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extarr11.aspx?memberKey1=ZZZZ&date1key=2020-02-28

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |