Russia and Conflicts in the Greater Caucasus: In Search for a Perfect Solution

Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti, Georgia

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D in History, Leading Research Fellow at MGIMO University, Editor-in-Chief of International Analytics Magazine

Covering the independent Transcaucasian states and the Russian Transcaucasian republics, the Greater Caucasus today appears to be one of the most turbulent post-Soviet regions. It was the Greater Caucasus that set the precedent of border-change in August 2008 among the former countries of the USSR. Because of the region’s global importance as caused by the involvement of such key international actors as the United States and the European Union, the time has come to try and forecast the future of potential conflicts in the Caucasus and identify feasible solutions for their resolution.

Covering the independent Transcaucasian states and the Russian Transcaucasian republics, the Greater Caucasus today appears to be one of the most turbulent post-Soviet regions. It was the Greater Caucasus that set the precedent of border-change in August 2008 among the former countries of the USSR. Because of the region’s global importance as caused by the involvement of such key international actors as the United States and the European Union, the time has come to try and forecast the future of potential conflicts in the Caucasus and identify feasible solutions for their resolution.

A Region Especially Important for Russia

After the breakup of the USSR and the emergence of the newly, independent states, the Caucasus, previously on the sidelines of world politics, has immediately attracted the attention of both neighbors and influential global players. Literally overnight, former Soviet republics have turned into international nation-states with their own national interests and foreign policy priorities.

It is hard to overestimate Russia’s role in the politics of the Caucasus, since Moscow regards the region as a territory of special importance in view of its strategic interests, primarily because Russia is also considered a Caucasian state. The North Caucasus is home to seven Russian republics, i.e. Adygea, Dagestan, Ingushetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Circassia, North Ossetia, Chechnya, as well as Krasnodar and Stavropol territories; all of them part of the North Caucasian and Southern federal districts.

As far as conflicts in the Caucasus are concerned, Russian diplomatic efforts have refrained from adopting a universal approach, instead relying on individual strategies for untangling the ethno-political mess that may appear too sophisticated to attributes of the state of confrontation between Russia and the West.

Most of the conflicts in the Russian Caucasus, both open and latent, are related to tensions within the former Soviet republics, and vice versa. The Georgia-Ossetian clash had a significant impact on the Ossetian-Ingush dispute, while tensions between Georgia and Abkhazia have influenced ethno-political processes in the western part of Russian Caucasus, i.e. in Adygea, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Circassia. Security in Dagestan and Chechnya is heavily dependent on the situation in the Pankisi Gorge, and the problem of separated peoples, such as the Lezgin and Avar, whose ethnic communities are divided on both sides of the border between Azerbaijan and Russia, impacts both regional dynamics and the Moscow-Baku relationship.

Hence, Russia’s Transcaucasian policy is to a great extent focused on support for and the improvement of the security environment in the North Caucasus, which remains Russia’s most troubled region.

As far as conflicts in the Caucasus are concerned, Russian diplomatic efforts have refrained from adopting a universal approach, instead relying on individual strategies for untangling the ethno-political mess that may appear too sophisticated to attributes of the state of confrontation between Russia and the West.

In the case of Georgia, in light of the absence of diplomatic relations, Russia does not recognize its territorial integrity and sees Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states. Moscow’s attitude to Azerbaijan is exactly the opposite, i.e. Russia recognizes its territorial integrity, regularly condemns any form of elections in present-day Nagorno-Karabakh which lies the jurisdiction of Baku, and actively cooperates with the U.S.A. and France in the (Minsk Group under the OSCE auspices.

As of now, Moscow, Washington and Paris have agreed on the so-called basic principles for the Armenian-Azeri settlement as the foundation for future peaceful relations [1]. Russia sees Armenia, a CSTO participant and potential member of the Customs Union, as its strategic ally, and at the same time does not want deterioration in its relations with Azerbaijan, since the two countries share a border in Dagestan and both have ethnic communities located on both sides. Having lost its levers of influence on Tbilisi, Moscow is trying to delicately navigate between Yerevan and Baku.

Russia and Georgia: Normalization in the Offing?

Can Russian-Georgian relations be restored?

Both countries appear to have many reasons to seek normalization. First of all, Georgian businesses are eager to sell to the Russian market [2]. Secondly, both countries are aware of common security threats along the Russian-Georgian border, i.e. within the Dagestan, Chechen and Ingush communities. Georgia has seen outbursts of domestic Islamic radicalization in the Pankisi Gorge and attempts by Muslim extremists to establish ties with their kin in the North Caucasus and the Middle East. Third, there are definitely areas of successful cooperation, for example the joint operation of the Inguri hydropower plant and the readiness the two sides demonstrated to coordinate security efforts during the Sochi Winter Olympics.

In the short and medium run, Russian-Georgian relations will be noticeably influenced by developments around Ukraine and Crimea.

At the same time, there are many obstacles to settling the ethno-political conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, as Moscow and Tbilisi completely disagree about the status of the two former Georgian autonomies. As such, Tbilisi enjoys massive support from the United States and its NATO and EU allies, only increasing Georgian leaders’ hope that Western pressure on Moscow will sooner or later materialize helping to secure a resolution of the problem of these separatist territories in their favor. As result, Georgia has little motivation to seek other solutions other than the “return of these separatist territories.” In the short and medium run, Russian-Georgian relations will be noticeably influenced by developments around Ukraine and Crimea.

The normalization of Russian-Georgian relations appears likely as long as Russia and the West can find compromise on relations within the post-Soviet space, while Washington and Brussels should agree on the informal recognition of these territories as part of Russia’s sphere of influence. Having abandoned hopes for NATO membership and cooperation with the West towards the containment of Russia, the new generation of Georgian politicians may in face radically change their approach to the idea of returning Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Making Russia socially, economically and politically responsible for the two problem regions, populated by ethnic minorities hostile to Tbilisi, could be a justifiable strategy according to Georgian, rather than Russian, interests. This approach is unlikely to find support, but the idea should gradually gain support among Georgian political and business elites, as had been the case with Serbia and Kosovo.

If antagonism between Russia and the West increases, Georgia may join Ukraine as an arena for confrontation, where the normalization of Russian-Georgian relations would either stagnate or come to a standstill. The outcome hinges on the degree of the conflict between Moscow and Washington, as well as on the involvement of other post-Soviet republics, for example Moldova suffering from the frozen conflict with Transnistria and other complications with Gagauzia.

For now, the initial stage of the process of normalization, marked by softer rhetoric and reinvigorated by the building of socio-economic relationships and the recognition of common threats emanating from the North Caucasus, appears to be over. The follow-up to this progress requires fresh ideas, which can only emerge only when the broader international relationship between Russia and the West becomes clearer.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Peace Process: Pragmatism as the Key Instrument

In May 2014, the open-ended ceasefire agreement governing the Armenian-Azeri dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh celebrates its 20-year anniversary, although true compromise formulas has yet to be established, primarily because the parties have shown little readiness for concessions. Both still regard settlement as victory rather than conciliation and rapprochement. One side is working towards the consolidation of military-political gains achieved in May 1994, while the other wants the restoration of territorial integrity, among other things, by military methods.

Reconcilement between the conflicting parties has been declared dozens of times, but after many such statements, Baku has invariably insisted on its "inalienable right for the restoration of the lost territories" and a "readiness" to allow Nagorno-Karabakh only "extended autonomy". For its part, Yerevan has focused on respecting the self-determination of the Karabakh Armenians, whereas the leaders of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, a de facto state, not without reason are demanding a role in negotiations. But does this mean that a settlement is doomed to failure?

In contrast to Georgia and Ukraine, the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process may signify real confrontation between Russia and the West. On the contrary, Moscow, Washington and Paris have long demonstrated a willingness to cooperate in advancing the peace process.

In contrast to Georgia and Ukraine, the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process may signify real confrontation between Russia and the West. On the contrary, Moscow, Washington and Paris have long demonstrated a willingness to cooperate in advancing the peace process. Moreover, Moscow's diplomatic efforts are invariably supported by the West, irrespective of dynamics in other post-Soviet confrontations. Support for this claim can be found in the fall of 2008, when the United States publicly supported the Kremlin's steps in the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement, i.e. the trilateral Russian-Armenian-Azeri presidential format. But neither Yerevan nor Baku is ready to achieve feasible compromises, compelling the intermediaries to maintain the peace process as an alternative to possible military revenge or a forcible violation of the status quo.

Due to ongoing transformations of the post-Soviet space following the situation with regards to Crimea and subsequent potential for border changes, the risk of war is growing on both sides the ceasefire line in Nagorno-Karabakh and along the internationally recognized Armenian-Azeri border. Accordingly, the key task of the OSCE Minsk Group has been to boil down the peace process in order to prevent a escalations within this environment. The peace process is going to proceed under its current framework, i.e. "neither war nor peace" with more meetings and discussions, while opponents will be sitting on the fence until Russia and the West define their relationship in the post-Soviet space.

If a compromise is to be found, the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process will have a chance for survival. However, further planning along these lines should exclude the single-act settlement allegedly able to bring about a comprehensive agreement. What is needed is a stepwise advance toward a compromise, with each step working towards gaining the mutual trust of the parties. Talks should be thoroughly cleansed of any misconceptions that deviate from the interests of real-life people. And only after the rivals achieve a settlement more advantageous than continued discord, can real progress occur.

In addition, the outcome of negotiations should not be predefined, as the predetermination of the status of the disputed will not help matters. The future of Nagorno-Karabakh is by no means feasible without attention being paid to the realities of the past two decades. The outright return of the disputed territories to their previous formal owner appears out of the question, while provoking the process of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic's ethnic self-determination also seems risky.

Hence, a practicable settlement arrangement might grow out of a series of agreements or even political bargains, rather than emerge as something imposed by opponents in advance. Because of this, the use of force must be prohibited from the settlement process for good, with "any solution but war" formula used as a possible core of the entire process. However, this solution only has a chance at succeeding if the key actors can agree about what the final goal looks like.

North Caucasus: Domestic Stability Guarantees Foreign Policy Success

Russia's current domination in the Greater Caucasus is the result of Georgia's fears, Azerbaijan's jealousy and Armenia's hopes for the status quo. However, despite these controversial assessments of Moscow's role, all three countries see Russia's failure in the North Caucasian as enormously dangerous, since these events might automatically open their countries to extremist elements deployed on the other side of the Caucasian Ridge.

Regional security matters should be regarded only in broader strategic contexts, such as the ethno-political advancement of the North Caucasus, Russia's overall religious and national policies, and the all-out approach to Transcaucasia.

As correctly noted by the U.S. political scientist Gordon Hahn, "the jihadists of Imarat Kavkaz threaten the South Caucasus, i.e. Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. An Imarat Kavkaz map posted on the Caucasian mujahidin website entitles the territory of Russia and the South Caucasus as "lands occupied by kathirs and murtads." Moreover, the Vilayat Dagestan of Imarat Kavkaz includes the Azeri Jamaat."

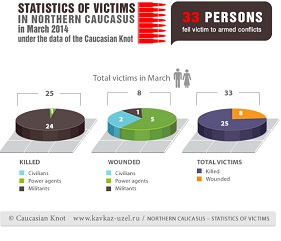

Meanwhile, claiming regional leadership, Russia is facing numerous problems on its own Caucasian lands. Between January 1 and December 30, 2013, the Southern and North Caucasian federal districts suffered 33 terrorist attacks. Although the current situation in the North Caucasus has failed to spur on Chechen separatist dynamics, instability has enveloped other North Caucasian territories, such as Dagestan, Ingushetia and Kabardino-Balkaria. Anti-Russian actions in the region have used mostly Islamist (jihadist) rather than nationalist slogans.

Statistics of victims in Northern Caucasus in

March 2014 under the data of the Caucasian

Knot

Moscow enjoys has many opportunities to contribute to the development of the North Caucasus, since its population has been fatigued by violence and many government agencies have developed relations with the rest of Russia. But progress requires concentration on several critical issues. Regional security matters should be regarded only in broader strategic contexts, such as the ethno-political advancement of the North Caucasus, Russia's overall religious and national policies, and the all-out approach to Transcaucasia. Along with technical steps to counter terrorist groups, Moscow should work out medium- and long-term ideological, socio-economic, cultural and humanitarian measures. Actions are needed for the effective regulation of domestic migration and the engagement of the North Caucasian population in the all-Russian projects, while government support of civil society in the Caucasian republics might help create the grass-root foundations for resisting the clan structures and corruption.

More attention should be focused on cooperation with Georgia and Azerbaijan, Russia's direct neighbors in the North Caucasus. The readiness for interaction on security during the Sochi Olympics could be used as an impetus for deeper cooperation in the future. It may also seem practicable to revive the idea of setting up joint antiterrorist centers discussed by Moscow and Tbilisi in 2004-2005 in the context of a possible reformatting of facilities belonging to the former Russian Group of Forces in Transcaucasia. Hence, opportunities have givern momentum to a normalization of relations with Georgia and the restoration of Russian influence in Azerbaijan.

Russia could apply the above steps to minimize any threats from the North Caucasian, increasing its own attraction with regards to its Transcaucasian neighbors and other post-Soviet states. Through the healthy development of the regional economy, Moscow could step up its integration efforts and acquire extra legitimacy as a mediator of conflict settlement. If instability prevails or the things go wrong, Russia could face higher risks as the turbulence of the North Caucasus could be used against its interests and influence in Transcaucasia.

Thus, the Greater Caucasus is a real, major ethno-political challenge for Russia and other actors with interests in Eurasia.

Russia possesses ample domestic and foreign policy resources to counter negative trends, among them its military capabilities, economic attractiveness, the interrelation of Russia's homeland security and ethno-political environment in Transcaucasian countries, the historic interaction background, numerous diasporas, etc. At the same time, all of these resources badly need better realization in absence the an integrated Caucasian policy incorporating both domestic and foreign policy measures – from relations with neighbors to sophisticated interaction formats with the far abroad – to the improvement of the situation appears doubtful. However, positive patterns also seemed unlikely if Moscow’s; partners fail to amend their approaches to Russian interests in Caucasus and the entire post-Soviet space by giving up demonization of Russian policies and comprehending Kremlin's rational motives and actions.

1. The document proceeds from the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan but at the same time specifies the intermediate status of Nagorno-Karabakh and determination of its final status through legally binding expression of popular will.

2. In January-September 2013, Georgian mineral water exports reached USD 22-24 million. In the final quarter of 2013, Georgian wine sales amounted to USD 40 million against less than USD 20 million in the beginning of 2013 (http://rus.ruvr.ru/2014_01_01/Vozobnovlenie-jeksporta-vina-v-RF-odno-iz-glavnih-sobitij-goda-dlja-Gruzii-4667/). In December 2013, Russia replaced Ukraine as the main importer of Georgian citruses (http://www.agroperspectiva.com/ru/news/128098).

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |