Russia and Ukraine Battling for Historical Truth

Prince Volodymyr the Great Monument, Kiev

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D. in Political Science, Head, Center for Social and Political Research, Institute for the Development of Integration Processes, Russian Foreign Trade Academy, Associate Professor, Financial University

Amidst the negotiation of an attempted settlement to the East Ukraine armed conflict, a new stage of information and ideological confrontation appears to be unfolding between Russia and Ukraine, this time about their past. In fact, the fabric of the history of the Kievan Rus looks very much like a blanket, with each country trying to pull all of it to its side. What we have seen so far has been sluggish but definitely intensifying jostling in the media, textbooks, movies and other cultural areas for the exclusive right to interpret the same historical facts. Why can’t these two states share a common history and why is it so important to possess a unique past?

Amidst the negotiation of an attempted settlement to the East Ukraine armed conflict, a new stage of information and ideological confrontation appears to be unfolding between Russia and Ukraine, this time about their past. In fact, the fabric of the history of the Kievan Rus looks very much like a blanket, with each country trying to pull all of it to its side.

What we have seen so far has been sluggish but definitely intensifying jostling in the media, textbooks, movies and other cultural areas for the exclusive right to interpret the same historical facts. Why can’t these two states share a common history and why is it so important to possess a unique past?

History for Substantiating Legitimacy

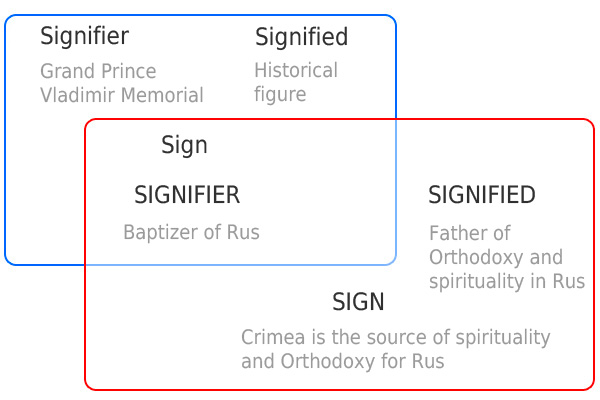

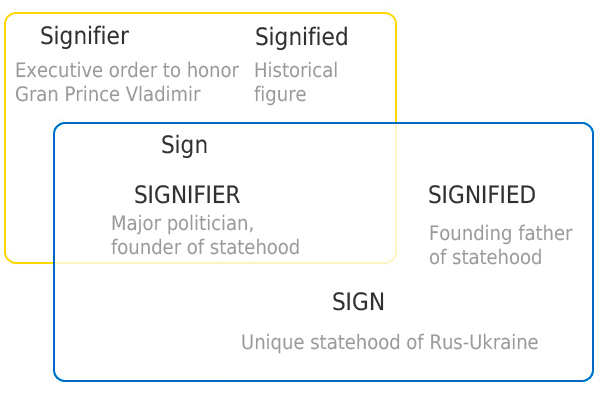

In his address to the Federal Assembly last December, President Vladimir Putin mentioned Grand Prince Vladimir of Kiev in the Crimean context, which was perceived by many that the affiliation of the peninsula was being legitimized through the myth of restoration, the historical truth and the preservation of continuity in traditions, culture and statehood. To this end, Moscow will erect a memorial to Vladimir on Vorobyovy Hills to honor the 1000-year anniversary of his death [1]. In his turn, Ukrainian President Poroshenko released an executive order to commemorate Grand Prince Vladimir as the "founder of medieval state Rus-Ukraine," [2] while the Russian State Duma responded by accusing Kiev of making an attempt to privatize the memory of Russia's Baptizer.

Although hardly breathtaking, these developments by all means affect the process of constructing and maintaining the authenticity of state borders, political regimes and national identity. Legitimacy is a notion widely used in this discourse – both in strictly academic and much broader, everyday terms. This article will analyze the historical side of the issue using the most topical case of the conflicting versions between Russia and Ukraine over their histories.

Millennium of Russia Monument, Veliky Novgorod

Whenever a new leader comes to power, he requires legitimacy, that is, a voluntary subordination and recognition of powers based on a universal understanding of social reality. The best explanation of the mechanism has been provided by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman, who defined legitimization as a process of forming the knowledge of the social and political system [3].

The system is created through secondary and university education, which gives rise to fierce battles over the content of history textbooks because the knowledge imbedded in the minds of young people shapes their commitment to the established institutions and rules. Protests against the legitimacy of the ruler never come out of blue and are preceded by changes in the education system or the emergence of a potent systemic, virus-like idea that conflicts with the mainstream.

Hence, legitimacy means something more than popular affection for the ruler – it is a sophisticated model incorporating knowledge, assessment and trust, which comprises several elements:

- Institutional order, signifying upright and equitable institutions that implement policies and distribute resources.

- A leader that displays personal characteristics and ideas that arouse trust and induce people to follow the established rules.

- Traditions that involve historical memory, cultural values and norms to materialize the principle that "things have always been this way and this is proper."

Protests against the legitimacy of the ruler never come out of blue and are preceded by changes in the education system or the emergence of a potent systemic, virus-like idea that conflicts with the mainstream.

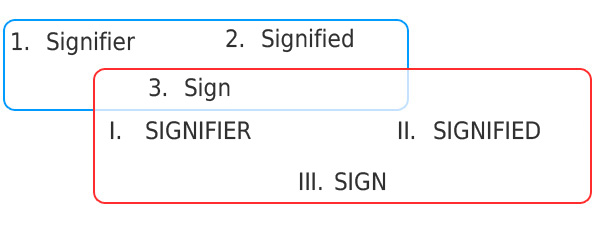

However, legitimacy is never given to the incoming ruler forever. With time, internal and external factors gradually undermine his validity, bringing up the need to prop up the structure and keep the political system running. This is normally done through the use of fresh ideas that do not radically alter the existing model (in this case radical refers to changing the model and revolutionary reforms), but rather effectively augment the scheme, improving its facade. In order to be accepted by society, new ideas that are introduced into the legitimization model should be palatable, with the most effective means for description and analysis of such myth-generated phenomena suggested by Roland Barthes. His connotation of myth is somewhat different from the common approach that usually arises when we refer to fairy tales and folklore. Myth is a communicative system that employs facts and signs to contribute additional meaning and form sophisticated and strongly symbolical structures that affect public consciousness. Myths are sourced not only by texts but also by images (paintings, photos and posters), movies, TV programs, etc., in other words by signs. In a semiotic system, we see a succession of signifier – signified – sign, while myth becomes a "second-order semiological system" with the sign working as the signifier [4].

Myth works as a prism to perceive the world, which in its turn forms the attitudes and finally behavior.

In politics, of primary significance are naturally statehood-related myths that explain the roots of the state, its borders and the names of the residents. To this end, the mythologization process to a great extent hinges on the interpretation of historical facts. The bitter struggle between Russia and Ukraine over the Kievan Rus naturally raises the question of why the states cannot have a shared past. As a matter of fact, a full-blown state should preferably have a unique history. Otherwise, it would feel like an underdog, especially vis-à-vis neighbor countries that boast a centuries-old history and traditions. Notably, this point is most significant for a nation state rather than for an empire or similar entities. As a rule, the restoration or creation of a unique history becomes an issue for the former colonies of a disintegrated empire [5].

Vladimir Putin and Pyotr Poroshenko Clash for the Grand Prince Vladimir

En route to statehood, Ukraine felt the impact of the powerful state and ideological machines of the neighboring Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

Having made history as the ruler who baptized Rus and bolstered its statehood (the key features attributed to him by history textbooks), Grand Prince Vladimir has recently emerged as a huge stumbling block for Russian and Ukrainian politicians.

The Tale of Grand Prince Vladimir Legitimizing Crimea inside Russia

The rule of Grand Prince Vladimir came to the forefront of the political debate in Russia after President Putin's address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation in December 2014. Below is the key quotation related to the analysis of historical myths and their role in current political processes.

Crimea is populated with our people and is strategically important because this is the seat of the spiritual source of the diverse but monolithic Russian nation and the centralized Russian State. It was here, in Crimea, in the ancient Chersonese, or in Korsun, as it was referred to by Russian chroniclers, where Grand Prince Vladimir received baptism to launch the christening of the entire Rus [6].

The national leader uses this excerpt to form a myth and authenticate the legitimacy of the political decision of annexing Crimea to the Russian Federation. In comparison with legal norms, historical legitimization is much stronger and more effective, since legal norms are derivatives of historical tradition and world vision.

Let us consider the Russian version of the myth structure.

In Russia, the deep-rooted historical legitimacy and continuity of historical epochs have not practically undergone any revisions, with all projects to interpret and describe history (Sergey Solovyov [7], Vassily Klyuchevsky [8], Sergey Uvarov's triad of Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality) working to build a single, non-contradictory historical model of development. With some slight variations, this scheme was taught both in the Soviet period and following the disintegration of the USSR. Nobody questions the Kievan Rus as the source of statehood and the Moscow Princedom and later the Russian Empire as its successor.

However, the political decision to annex Crimea had been perceived ambiguously both in Russia and abroad and hence has required additional legitimization. The new mythologem is intended to smoothly integrate the current political reality into the existing legitimization model and provide it with additional fixtures.

As far as Ukraine is concerned, the legitimization of its statehood is a much more complicated affair.

The Tale of Grand Prince Vladimir Legitimizing the Ukrainian State

The executive order of President Poroshenko to honor Grand Prince Vladimir was meant as a reminder that this relevant period is a part of Ukraine's history. Within the current quagmire of problems over the legitimacy of borders, Ukrainian national identity and diminishing political support, this order was designed to preserve available structures and the legitimacy model. Because of this, the political effect appears quite questionable.

As compared to Russia, historical legitimization is a much more difficult endeavor for Ukraine. En route to statehood, Ukraine felt the impact of the powerful state and ideological machines of the neighboring Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. And it was Mikhail Grushevsky who launched the construction of the model for a unique Ukrainian history when nation states emerged after the breakup of these empires. His project largely reflected the decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was briefly attempted during the revolutionary reforms in the Russian Empire. The scheme was revived in 2004 by the instigators of the Orange Revolution and incumbent President Pyotr Poroshenko.

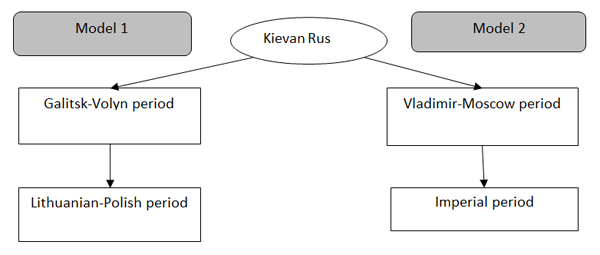

In 1898, Mr. Grushevsky released the first volume of History of Ukraine-Rus [9] that contained a compilation of facts intended to substantiate the historical independence of the Ukrainian people by tracing an alternative succession of historical stages. He rejected the unity of eastern Slavs, drawing a line between the Ukrainian-Russian people and Great Russians. Before Mr. Grushevsky, Ukrainian history had one way or another been integrated into the histories of Russia and Poland, the neighbor powers controlling Ukrainian territories. Accordingly, his innovation suggested an alternative model of historical development and a new succession in the continuity of state entities seen as the forerunners of modern Ukraine.

Alternative Histories of Ukraine

Mr. Grushevsky discarded the Muscovite version of history, insisting that although the Kievan Rus transferred some forms of the socio-political order to the Great Russia lands, there was no full-fledged continuity between the Kievan Rus and Moscow Princedom. The Tatar invasion undermined the socio-political basis of the Kievan Rus. East of the Dnieper River, these traditions were practically ruined, with only some of them preserved on the right-hand side and advanced in the Galitsk-Volyn Princedom and later under the rule of Lithuania and Poland. The version of history developed by Moscow was also unfit for legitimizing Ukrainian statehood because the emergence of the Ukrainians as a separate people was dated to the 14th-15th centuries, something was absolutely unsuitable for Mr. Grushevsky as the ideologue of the Ukrainian statehood.

As before, the key issue still lies in establishing the successor of the Kievan Rus.

As before, the key issue still lies in establishing the successor of the Kievan Rus. Prior to the arrival of Mr. Grushevsky's interpretation, the succession of the Kievan Rus and Tsarist Russia had been universally recognized (see V.M. Solovyov, V.O. Klyuchevsky). The incorporation of the Kievan Rus period into the historical roots of a state proceeds from the establishment of a certain state entity through a certain ethnos. Proponents of the unity of the three eastern Slavic peoples agree that the Kievan Rus was set up by the Slavs, who later gave rise to the Russians, Ukrainians and Byelorussians. In his History of Ukraine-Rus, Mr. Grushevsky not only substantiated the autochthony of the Ukrainian ethnos's origin but also firmly insisted that the Kievan Rus belonged to the tradition of the Ukrainian statehood.

This concept smoothly resonates with the current official Ukrainian debate because it provides grounds for the logical construction of national identity. Ukrainians assert that Moscow was built on its own, borrowing practically nothing from the Kievan Rus under immense Tatar influence.

Although ancient history, the two historical paradigms are popular in modern politics, with the described myths being only a fracture of the entire mythology arsenal employed in the debate. The history of the Great Patriotic War actually plays the same role, the most cited points being the dichotomy of the Soviet troops and collaborationists on occupied Ukraine territory, the odious Stepan Bandera, Golodomor, etc. The interpretation of concrete events and the formation of myths (as semiotic systems) helps to assign the friends and foes and also validate political decisions.

***

Although Russian and Ukrainian leaders use the same historical facts surrounding the Kievan Rus, their motivations differ. While Russia wants to add additional legitimacy to its political decision over the voluntary entry of Crimea into the Russian Federation, Ukraine is trying to restore the shattering legitimacy of its state borders and the national identity of its population.

The use of historical facts is a long applied instrument for fueling an entire political context, usually with quite material consequences. In fact, turning the status of Crimea into the historical center of Russian statehood may create a stumbling block during zero-sum international negotiations. If the partners opt for a more constructive approach to handle other issues, Crimea should be off the agenda. Ukrainian legitimacy appears more threatening. Independent for over 20 years, Kiev has failed to generate a state-wide identity and is now trying to revitalize older models, which have regrettably demonstrated their ineffectiveness after Maidan 2004. The country will face the irreparable loss of its legitimate borders and government, as well as the identity of its population.

In a situation like this, Russia and the West appear to have coinciding interests in handling the issue of Ukraine's legitimacy because neither would like to see a Somalia-style failed state at their borders. This move should be affirmative, shedding the extremes a la "Ukraine is not a state," etc., since this is a field for determined efforts to establish a constructive myth for a state on the verge of breakdown.

1. Location for Prince Vladimir Memorial Found in Moscow // RIA Novosti, February 11, 2015 // http://ria.ru/religion/20150211/1047165383.html (in Russian)

2. Poroshenko Gives Rus'-Ukraine Creator label to Prince Vladimir // Lenta.ru, 25.02.2015 // http://lenta.ru/news/2015/02/25/poroshenko/ (in Russian)

3. See: Berger P., Luckman T., The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise its the Sociology of Knowledge. Moscow, 1995.

4. See: Barthes R. Mythologies. Moscow, 2008. Pp. 266 – 271 (in Russian).

5. Ilia Garashanin in Serbia, Mikhail Grushevsky in Ukraine, and Sergey Solovyov in the Russian Empire.

6. Putin V.V. Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly. December 4, 2014 // URL: http://kremlin.ru/news/47173

7. Solovyov S.M. History of Russia from Ancient Times.

8. Klyuchevsky V.O. Russian History. Full-Time Course.

9. Later a more readable version of this concise Ukrainian history course was released. See: Grushevsky M. An Illustrated History of Ukraine. Moscow, 2001.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |