Russia–Azerbaijan: an ambivalent partnership

Baku, August 2013br

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D in History, Leading Research Fellow at MGIMO University, Editor-in-Chief of International Analytics Magazine

Following the disintegration of the USSR and the emergence of newly independent states, the Caucasus region, which for years had stayed at the periphery of world affairs, has found itself the focus of attention from influential international players as well as neighboring countries. The emergence of independent states in the South Caucasus went hand-in-hand with attempts to advance new regional security mechanisms and new forms of international cooperation. Analysis of bilateral Russian-Azerbaijani relations is key to understanding political developments across the post-Soviet Caucasus in all their complexity.

Following the disintegration of the USSR and the emergence of newly independent states, the Caucasus region, which for years had stayed at the periphery of world affairs, has found itself the focus of attention from influential international players as well as neighboring countries. Former Soviet Transcaucasia republics, which became subject to international law overnight, began to formulate their own national interests and foreign policy priorities. The emergence of independent states in the South Caucasus went hand-in-hand with attempts to advance new regional security mechanisms and new forms of international cooperation.

Analysis of bilateral Russian-Azerbaijani relations is key to understanding political developments across the post-Soviet Caucasus in all their complexity.

Azerbaijan: locked between Armenia and Georgia

Azerbaijan has a unique place in Russian policy in the Caucasus today, staying aloof from the extreme poles of Armenia and Georgia. Armenia is Russia’s strategic ally, and a member of the Collective Security Treaty in the Customs and Eurasian Unions. By contrast, Georgia has no diplomatic relations with Russia, which it treats as an occupying force in possession of two of its regions (Abkhazia and South Ossetia); Georgia seeks integration with NATO and the EU, and engages actively in military operations by the US and its NATO allies worldwide.

Russian diplomacy treats Azerbaijan as a strategic partner, based on a number of factors.

Firstly, the two countries share land borders in Dagestan (284 km) and maritime ones in the Caspian Sea.

Moscow sees its role in the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process as a way of preserving its influence across the South Caucasus, as well as an additional opportunity for constructive dialogue with Western partners.

Secondly, there is the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, in which Russia is involved. Russia is trying to maintain the status quo, and to rule out a military solution to this conflict along the lines of the South Ossetia scenario of 2004-2008. Unlike the situation in Georgia, and the two ethno-political conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Russia’s contribution to the peace process there is supported by the US and the European Union. Together with Washington and Paris, Moscow co-chairs the OSCE Minsk Group securing the negotiation process between the conflicting parties and the development of a formula for a final settlement. Both the US and France supported Moscow’s efforts in the 2008-2011 trilateral talks (Russia – Armenia – Azerbaijan). In fact, Moscow sees its role in the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process as a way of preserving its influence across the South Caucasus, as well as an additional opportunity for constructive dialogue with Western partners.

Thirdly, Azerbaijan holds a strategically important position as a link between the Greater Caucasus and Central Asia (via the Caspian Sea) on the one hand and the Middle East (through shared borders with Iran) on the other.

Fourthly, this Caspian republic is the fastest growing economy in the South Caucasus. According to the World Economic Forum, in 2012 Azerbaijan was one of the top 50 countries by level of economic competitiveness; it has also retained its leadership among the CIS countries in terms of GDP growth rates.

Fifthly, the two countries’ bilateral relations owe a lot to diasporas (Azerbaijanis in Russia, and Russians and Dagestanians in Azerbaijan). According to the 2010 census in Russia, there are about 603,000 Azerbaijanis residing there. The Russian Federal Migration Service claims that there are up to 620,000 migrants from Azerbaijan in the country.

Stanislav Chernyavsky:

Azerbaijan and Russia: the present and

the future

Over the past two decades, the number of ethnic Russians in Azerbaijan has more than halved, from 392,000 in 1989 to 119,000 in 2009. However, they have remained the third largest ethnic group in the country after Azerbaijanis and Lezgians. The Lezgian ethnic territory is now divided between southern Dagestan in Russia and northern Azerbaijan, while Azerbaijanis in the largest North Caucasian republic belong to the sixth largest ethnic group, accounting for 4.5 per cent of its total population.

As for Baku’s choice of ways, Azerbaijan has so far shown a selective approach to its cooperation with Moscow. While Azerbaijan considers Russia an important and beneficial partner in relation to a range of issues, there are also areas where the latter is an obvious rival.

Forms of cooperation

Azerbaijan is undoubtedly interested in promoting trans-border cooperation with Russia. Russia was the first of Azerbaijan’s Caspian neighbours to have reached, in September 2010, an agreement on delimitation and demarcation of borders, after fourteen years of difficult negotiations. In July 2011, the heads of the foreign offices of the two countries exchanged instruments of ratification. Quite important for bilateral relations is the direct dialogue between Azerbaijan and Dagestan, the largest North Caucasian republic of Russia. The Dagestani authorities are playing a prominent role in resolving the issue of the two Lezgian enclaves (Khrakhoba and Uryanoba) inhabited by Russian nationals that, following the delimitation and demarcation, found themselves in Azerbaijani territory. During the official visit by the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, to Baku in August 2013, the countries discussed prospects for the construction of a highway bridge across the Samur River.

In 2010-2012, a few package deals were agreed for the supply of arms from Russia to Azerbaijan, and in 2013 Russia started the deliveries under the 2011-2012 agreements.

Azerbaijan seems keen to maintain cultural and scientific contacts with Russia. The republic has over 300 Russian language schools with 80,000 pupils. In 2008, a branch of the Moscow State University was opened in Baku. In other universities, Russian has been included among mandatory subjects of the curricula.

Concerned by the expansion of Islamism both inside the country and across neighbouring regions in the Russian Federation (especially in Dagestan), Baku seems eager to collaborate with Moscow in security issues.

Despite the strategic alliance between Moscow and Yerevan, Russia pursues military and technological cooperation with Azerbaijan, begrudged by Yerevan but supported by Baku. In 2010-2012, a few package deals were agreed for the supply of arms from Russia to Azerbaijan, and in 2013 Russia started the deliveries under the 2011-2012 agreements. During President Putin’s visit to Baku in August, this area was stated to be among the priorities for bilateral cooperation in future. According to Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, military and technological cooperation between the two countries today amounts to almost USD 4 bln, and “tends towards growth”.

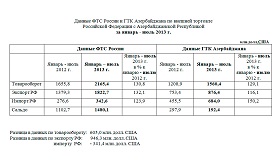

However, the USD 3 bln of bilateral trade in 2012 was hardly impressive, and was less than that between Azerbaijan and Israel.

There is another important aspect, that of money remittances from Russia by labour migrants. In 2012, they increased by 6 percent and reached USD 1.23 bln.

The presidents of Armenia, Azerbaijan and

Russia signed the declaration on the resolution

of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict, 2008

The Russian leadership has been unfailing in its support for the incumbent Azerbaijani government. It lent its support in the course of parliament elections in 2005 and 2010, during the 2008 presidential election and the 2009 constitutional referendum which effectively granted the incumbent president the right to run for the presidential office for more than two consecutive terms. The 2013 presidential election was no exception, and President Putin’s August visit to the Azerbaijani capital, too, was viewed in this context.

Geopolitical differences

At the same time, Azerbaijan is not fully satisfied with the Russian position on the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement. Russia is trying to find a balance between Baku’s interest in re-establishing control over the Nagorny area and the Armenia-controlled ones beyond, and Yerevan’s official position. Russian military and political cooperation with Armenia, a strategic opponent, causes Baku clear concern. Armenia is the only state in the South Caucasus to be party to the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). It houses Russian troops (the 102th military base at Gyumri) as well as border guards, and the Military Base Treaty has been extended till 2044.

Azerbaijan is not fully satisfied with the Russian position on the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement. Russia is trying to find a balance between Baku’s interest in re-establishing control over the Nagorny area and the Armenia-controlled ones beyond, and Yerevan’s official position.

Nevertheless, Azerbaijan has refrained from any attempts to unfreeze the conflict, in contrast to what Georgia did in 2004-2008. Official Baku draws an express line between harsh rhetoric for domestic use, and its support to the constructive efforts by Moscow, Washington and Paris within the framework of the OSCE Minsk Group. While in Baku in August 2013, the Russian president reiterated the unchanging Russian position on peaceful and political resolution of the ethno-political confrontation between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and President Ilham Aliyev talked positively about Moscow’s peace-making efforts .

While Azerbaijan does contribute to NATO projects, unlike Georgia it is in no hurry to accede to the alliance. Its cooperation with Brussels is limited largely to technical issues. Baku is taking its time introducing civilian control over national defense and making its army compatible with NATO standards. In fact, in May 2011 Baku officially joined the Non-Aligned Movement, which holds the supreme goal of non-participation in any military blocs.

Competition and the Western factor

On 20 September 1994, at the famous Gulistan Palace in Baku, Azerbaijan and 12 Western oil majors signed the “contract of the century”, which was to become one of the largest business contracts over the past two decades and, in many respects, the mainstay of Azerbaijan’s foreign trade and foreign policy. Baku cleverly structured its strategy to fit the energy-related phobias in the US and EU, with their fears of Russia’s “oil and gas weaponry” and of the “energy empire” thought to be trying to restore the USSR. The “energy alternative”, embodied in the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline, has helped to strengthen Azerbaijan’s positive image in the West. During the August 2013 visit by Vladimir Putin to Baku, Rosneft signed an agreement on trade cooperation with SOCAR, the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan, although the Russian company was not allowed an interest in the Absheron gas condensate field.

At the same time, almost a third of all NATO cargo from Europe destined for Afghanistan is today going through Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan has been looking for a counterbalance to Moscow and the Armenian lobby in the US and Europe, trying to win support of certain Western circles to render the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement in its favor

Baku sees obvious benefits from its cooperation with the West. Firstly, it helps mitigate Western criticism of its domestic policies (where power is passed on from father to son, and kept within the Aliyev family). As such, if the US does criticize Azerbaijan for breaking with democratic canons, it is rarely in public.

Secondly, Azerbaijan has been looking for a counterbalance to Moscow and the Armenian lobby in the US and Europe, trying to win support of certain Western circles to render the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement in its favor; hence its involvement in such pro-Western integration entities as the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development. Although this antithesis of sorts to the CIS is not particularly active or effective right now, there are no plans to disband it. Judging from the events of 2005-2008, it may find a new lease of life under the right circumstances. In the past, it used to significantly undermine mutual understanding between Moscow and Baku.

Nor should should one discount Azerbaijan’s participation in the European Union’s Eastern Partnership project, although joining the EU has never been a strategic goal for Baku. That said, any EU interest in taking the Caspian republic into its fold would hardly look credible either.

Baku is skeptical of any integration project under Moscow’s auspices, and so Azerbaijan has not joined the Free Trade Zone Treaty signed in October 2011 by eight CIS countries (and also joined later by Uzbekistan). At the session of the Customs Cooperation Council and Global Excise Summit at the World Customs Organisation’s headquarters in Brussels (June-July 2012), Azerbaijan’s delegates announced that they had no intentions of joining the Customs Union. Baku is also very suspicious of the CSTO, all the more so as Russian officials and CSTO functionaries have repeatedly stated that any foreign aggression against Armenia will be treated as a challenge to Russia. In addition, Russia continues to supply military hardware to Armenia, a CSTO member, at discount prices, whereas Russian-Azerbaijani contracts are priced at full market value.

Baku wants to get supplies of Russian arms, but is wary of Russia’s military presence inside the country. And although bilateral talks on the prolongation of the 2002 agreement, allowing Russia to rent the Gabala Radar Station in Azerbaijan, had been in progress since summer 2011, the two countries failed to agree on the amount of rent (Baku first wanted to raise it from USD 7 mln to 150 mln, and then to 300 mln). As a result, on 12 December 2012 radar operations were suspended. However this was hardly a catastrophic loss for Russia, as another radar station was commissioned in the Krasnodar region, similar in purpose but better equipped. As a result, the lack of compromise between Moscow and Baku on the Gabala Radar Station failed to chill the relations between the two countries in any significant way.

The spectrum of opportunities

Russian-Azerbaijani relations are extremely contradictory. And while both countries have vested interest in maintaining them at an adequate and constructive level, Moscow is not prepared to side fully with Baku in the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, and turn its back on Armenia. For Russia, as well as the West, the optimum solution today is the status quo. Translated from diplomatic language, this means the unwillingness of Moscow to unfreeze the conflict following either the South Ossetia or the Abkhazia scenarios. Russian diplomacy seeks to preserve the fragile balance between Yerevan and Baku, particularly after the events of August 2008, when Moscow lost its positions in and leverage over Georgia.

While its repudiation of an alliance with Armenia might be supported and welcomed in Baku, Azerbaijan itself will never take a sweeping turn towards favoring Russia, given its strong ties with Turkey, the US and the EU.

Armenia has a Russian military base while Azerbaijan has a common border with Russia in Dagestan. Any further destabilization in that part of the Caucasus is not something either Russian or Azerbaijani authorities would want. Moscow cannot be unaware that while its repudiation of an alliance with Armenia might be supported and welcomed in Baku, Azerbaijan itself will never take a sweeping turn towards favoring Russia, given its strong ties with Turkey, the US and the EU. In addition, this hypothetical change in Russia’s policies towards the Caucasus would undermine its mediation role in the Nagorno-Karabakh settlement. Yet it is exactly this role that Moscow uses both as a trump card in its dealings with Yerevan and Baku, and as an important argument in structuring its relations with Western partners.

While they continue to pursue their mutually beneficial cooperation with the West in the energy sector, Azerbaijani authorities do not want to see their country involved in any US-led operation against neighbouring Iran or Syria (Teheran’s strategic ally). Hence the extremely cautious reaction that Azerbaijan showed towards the recent initiative potentially aimed at toppling Bashar Assad’s regime with outside intervention.

Prospects for Russian-Azerbaijani relations depend on a whole range of factors. The first one is the preservation of the status quo around Nagorno-Karabakh. Then there are such background factors as the overall situation in the Middle East, the development of the internal conflict in Syria, and the relationships between Iran and Israel as well as Teheran and Washington. In these circumstances, Moscow will want to maintain constructive relations both with Yerevan and Baku, and with its Western partners in the OSCE Minsk Group.

And although this may not be exactly to Azerbaijan’s taste, its political resources today are not strong enough to effect any drastic change. The risk of confrontation with the Russia-led CSTO is too high.

As for the West, in contrast to Georgia, the US and the European Union are not prepared to make an unequivocal choice between Azerbaijan or Armenia. Moreover, Western countries do not view the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as a platform for competition or rivalry with Russia. Under the circumstances, any attempt at seeking military revenge is likely to result in a protracted war and painful domestic political spillover for the incumbent powers in Azerbaijan. All these considerations keep Azerbaijan from any gambles or reckless moves.

Thus, unless Baku follows Mikheil Saakashvili and tries to unilaterally disrupt the status quo and attempt to change the format of the negotiation process, relations between Russia and Azerbaijan are likely to remain at their current level. Otherwise there is a high probability of a sharp downturn leading to a painful confrontation. As for the Middle East, the developments there are hard to predict, and furthermore their detailed consideration goes beyond the scope of the topic proposed in this paper. But whatever course events in the Middle East might take, Moscow and Baku have a wide range of options for matching their positions on this issue, as both are concerned by the rise of radical political Islamism at their borders, and by the risk of having both outside players and neighbouring countries involved in Caucasus affairs.

Recommendations

For Moscow and Baku to continue their constructive bilateral relations, maintaining their “agreement to disagree”, appears to be the best option today. It would be extremely perilous for Russian diplomacy, which forfeited its leverage over Georgia in August 2008, to lose its influence over one of the Caucasus republics still remaining in its orbit. For Azerbaijan, in turn, any repetition of the “Georgian way” would spell a protracted unfreezing of the conflict, with predictable intervention from outside and an unpredictable outcome.

It is therefore vital to continue to develop the areas that have proved positive so far: cultural and scientific contacts, economic collaboration and anti-terror and special services interaction around Dagestan. It is essential to focus on those issues that have come to the fore as a result of compromises and agreements already achieved.

In terms of trans-border cooperation, Russia and Azerbaijan would need to once again address the issues faced by the two enclaves, Khrakhoba and Uryanoba. As mentioned, they are inhabited by Russian nationals who found themselves in Azerbaijani territory following the completed demarcation. There is a need to resolve issues pertaining to their status, and organized rater than forced resettlement. Without addressing these problems, the “Lezgian issue”, which could potentially help bring the two countries closer, may instead become an additional separating factor.

In addition, Russia would do well to resume the trilateral talks on Nagorno-Karabakh which, apart from allowing Russia to participate in the OSCE Minsk Group, promote its exclusive role in the peace process, without mixing up its national interests with international engagement. It is important to remember, however, that no matter how active Moscow is in this role, without willingness to compromise on the part of Baku and Yerevan this lingering ethno-political conflict appears impossible to resolve.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |