The Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia: gains and losses

Chinatown, Bangkok

(votes: 2, rating: 4.5) |

(2 votes) |

PhD in History, Leading Researcher at RAS Institute for Far Eastern Studies

Thanks to its unique internal organizational qualities and business-related skills, the Chinese diaspora is making key contributions to the development of Southeast Asia, assisting countries in the region in improving their economic fundamentals and their integration into global markets. At the same time, the dominance of Chinese minorities in very profitable sectors and in the export of capital to the PRC is causing suspicion among indigenous populations. China's rapprochement with the ASEAN is not only strengthening diaspora peoples and boosting their business prospects, but also generating alarmism amongst the locals.

Thanks to its unique internal organizational qualities and business-related skills, the Chinese diaspora is making key contributions to the development of Southeast Asia, assisting countries in the region in improving their economic fundamentals and their integration into global markets. The latest migration wave from China has increased the ranks of Chinese communities abroad, giving impetus to further economic activities. At the same time, the dominance of Chinese minorities in very profitable sectors and in the export of capital to the PRC is causing suspicion among indigenous populations. China's rapprochement with the ASEAN is not only strengthening diaspora peoples and boosting their business prospects, but also generating alarmism amongst the locals.

Without a doubt, these divergent trends are bound to continue.

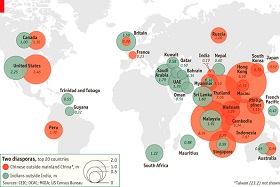

The Third Global Economy

As the world’s largest diaspora population, the Chinese diaspora is estimated at 50 million people, residing in practically every country around the world. In 2003, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, one of the leading Asian politicians, called it the third global economy after the U.S.A. and Japan, having assessed its total capital at USD 1,500 billion [1]. With every year, this sum increases, as the number of top companies belonging to ethnic Chinese in other countries grew by 111 percent from 2001 to 2008 [2].

China is proud of its diaspora. In his address to the 12th World Chinese Enterpreneurs Convention in September 2013, President Xi Jinping wrote: “Thanks to their hard work and magnificent traditions, Chinese businessmen abroad live in harmony with all peoples of the world and contribute greatly to the international economy and social progress.”

China is proud of its diaspora. In his address to the 12th World Chinese Enterpreneurs Convention in September 2013, President Xi Jinping wrote: “Thanks to their hard work and magnificent traditions, Chinese businessmen abroad live in harmony with all peoples of the world and contribute greatly to the international economy and social progress.” [3]

The diverse nature of Chinese emigration has been prolifically described, but its economic activities, the foundation of its existence, are grossly under-researched, both due to the secretive nature of many of the internal organizational processes and the delicate nature of the subject, which prevents various surveys and statistical collections. This article will cover only a comparatively narrow theme, i.e. the pros and cons of the Chinese diaspora's economic activities for the ASEAN countries, which host over 70 percent of emigrating Chinese and whose economies are most influenced by Chinese minorities, as seen from the table below.

| Country | Share of population, percent | Share of GDP, percent |

|---|---|---|

| Thailand | 3 | 60 |

| Indonesia | 4 | 70 |

| Philippines | 3 | 70 |

| Malaysia | 30 | 50 |

| Singapore | 75 | 90 |

Source: www.amk.fi

Certain sectors of ASEAN economies are almost under the complete control of Chinese diasporas. For example, the Chinese stake in Thailand’s trading and industry sectors has reached 90 percent [4].

Chinese minorities focus on services, trading from retail to real estate operations, hotels, finances and banking, metallurgy, chemicals, light industry, foods, construction, high added value agriculture, and manual labor in mining. Along with small and medium firms, they also employ large financial-and-industrial groups, sometimes JVs with locals, as in Indonesia.

Being Chinese is a Passport to Success

Historically, Chinese minorities have faced numerous difficulties, the worst being conflicts with the indigenous population, which in many cases have become very tense. The core of the disputes has invariably been economic, i.e. business and hired-labor competition between the Chinese and locals, as well as the natives' discontent over immigrants' savings being repatriated in their homeland. Local authorities frequently discriminate against the Chinese who, in turn, have made up their losses by cooperating with local bureaucracies. This has given rise to the clientelistic relationships, cronyism and all-inclusive corruption, such as what has happened in Indonesia.

Despite a complicated historical environment, the Chinese diaspora became an essential part of the ASEAN economies back in the pre-colonial times; since then, including into the present day, the diaspora’s capital, labor and business skills have become a major part of these countries’ economies.

Western, Chinese and Southeast Asian scholars have thoroughly analyzed the reasons for the Chinese’s impressive economic results [5], which in a nutshell boil down to the following:

- Personal traits of the Chinese, i.e. diligence, intelligence, thriftiness, quick learning, and entrepreneurship.

- The family-business approach.

- Informal intra-diaspora links, which has facilitated the timely exchange of business information, deal-making processes and the completion of transactions built on mutual trust, helping bypass cumbersome and mostly unreliable formal procedures, i.e. the so-called bamboo network. Family, intra-clan and community-wide ties intermingle with business and open access to domestic and international markets.

- The sense of belonging to the great Confucian culture unites the Chinese, making them proud of their nation and confident in professing ideological support for the family business pattern and hierarchical relations within the community.

Chinese minorities focus on services, trading from retail to real estate operations, hotels, finances and banking, metallurgy, chemicals, light industry, foods, construction, high added value agriculture, and manual labor in mining.

Many scholars tend to amalgamate the above points into the aggregate Chinese spirit, the secret of success of its bearers. The Chinese spirit is definitely a key reason behind the accomplishments of the Heavenly Empire messengers in the Russian market, the main factors being personal qualities and informal links within the Chinese community.

The New Wave of Emigration

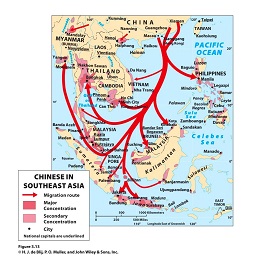

The mass migration of the Chinese to Southeast Asia has a long history, with the first wave of merchants and craftsmen dating back to the 17th century. China's defeat in the mid-19th-century Opium Wars generated the second wave of mostly coolies. Diverse in composition, the third wave occurring during the 1920s-1930s was caused by the economic rise of Southeast Asia. The establishment of the Peoples' Republic of China brought an end to emigration, as Beijing closed its borders because of the confrontation of the two social systems, while the Southeast Asian states strictly banned immigration from China; this step actually complicated the life of Chinese communities abroad [6].

In the early 1980s, the PRC undertook reforms and a move towards openness that produced impressive growth and strengthened Chinese diasporas living in foreign countries, giving them solid support and actually changing their entire image abroad. In addition, this new wave of emigration considerable increased the total population of the Chinese diaspora. According to Chinese experts, beginning from the late 1970s, over 10 million Chinese left their homeland, most of them moving to industrialized countries (seven million in total) and about three million to emerging economies, mainly to Southeast Asia.

The new migrants significantly differ from the previous waves. They are knowledgeable; many of them boast high-school or university educations received at home. They maintain close links with their homeland, whereas the previous generation, primarily young people born abroad, are to a great extent separated from their native country and frequently have no command of the Chinese language.

New migrants in Southeast Asia are economically concentrated in the trade and services sectors. There are also small groups of engineers and technicians, hired hands, farm workers, teachers and creative professionals. A special contingent comprises employees and workers of Chinese contractors carrying out construction projects abroad and using the workforce brought from the PRC.

Despite a complicated historical environment, the Chinese diaspora became an essential part of the ASEAN economies back in the pre-colonial times; since then, including into the present day, the diaspora’s capital, labor and business skills have become a major part of these countries’ economies.

Intensive inegration with China has flooded ASEAN countries with Chinese goods and created more jobs, with investments also growing, although not to a very large degree – USD 2.78 billion in 2010 and USD 6.03 billion in 2011 [7]. In other words, a new economic environment has emerged with clear opportunities for local ethnic Chinese. ASEAN governments have radically modified their policies toward Chinese minorities, who have acquired more opportunities for expanding their activities, among them the cancellation or softening of discriminatory laws, the improved treatment of the capital of the Chinese diaspora as a major element of nation building, the resumption of education in Chinese which had previously been banned and which has become essential in the new economic environment, etc.

Back in 1980, the government of Indonesia, whose history is permeated with drama in relation to the Chinese community, legalized the right of ethnic Chinese to become naturalized citizens, an act that extended to 700,000 people. Jakarta has taken up the policy of cultural pluralism, and has introduced religious liberties and the Chinese language into the secondary school curriculum, with teachers being invited from the PRC.

Gains and Challenges in the Same Package

However, the contribution of Chinese minorities to Southeast Asian economies is somewhat ambiguous. These economies are definitely experiencing gains from Chinese labor, capital and business skills. Chinese minorities are contributing to increases in GDP, exports and average incomes. (In 2003-2007, the average GDP growth rate was 6.1 percent, with the OECD forecast for 2011-2015 at 6.0 percent [8]. Exports in 2012 reached USD 195.8 billion [9], i.e. 17 percent higher than in 2010 [10]. Per capita income in 2012 amounted to USD 3,747 in current prices and USD 5,790 with the PPP [11], whereas in 2008 it was at USD 2,577 and USD 4,726 respectively) [12]. Chinese international business ties have assisted Southeast Asian countries in integrating into the global market. Generating no high-tech of their own, the Chinese have brought proven technologies from the industrialized world. Notably, several corporations led by Chinese migrants are already listed among the 500 largest transnational corporations [13]. Chinese emigrants have also considerably contributed to the development of economic and cultural ties between Southeast Asia and the PRC.

At the same time, the populations of the host countries regard some of activities undertaken by the Chinese diaspora as infringing upon their own interests.

Partly through successful competition and partly through capturing open niches in the labor market, the Chinese have managed to grab the most lucrative sectors, leaving locals with less profitable and less efficient areas, primarily farming and mining. According to some experts, during the colonial period, the Chinese diaspora become rich by participating in the exploitation of natural resources and local labor, serving as a mediator between the colonial powers and host markets. Today, the ethnic-oriented division of labor remains due to the competitive advantages of the Chinese. At the same time, analysts believe that discrimination towards Chinese minorities on economic grounds has been a key reason for the delayed transition of Southeast Asia into high-efficiency industrial economies.

Also bad for local economies is the transfer of Chinese savings to their homeland, which has been in existence as long as the Chinese diaspora itself. In recent years, exported sums have soared as the diaspora’s investments in the PRC are more than double those in the ASEAN. (As of June 2013, FDI from ASEAN countries into the PRC were mainly from ethnic Chinese and exceeded USD 80 billion, with FDI from China into the ASEAN was USD 30 billion) [14]. Whereas Beijing is happy to encourage such injections of capital into its national economy, the involuntary donor countries suffer from the unwanted flight of capital generated in their territories, not only by the Chinese but also by the indigenous population.

The new migrants significantly differ from the previous waves. They are knowledgeable; many of them boast high-school or university educations received at home. They maintain close links with their homeland, whereas the previous generation, primarily young people born abroad, are to a great extent separated from their native country and frequently have no command of the Chinese language.

Notably, some pundits also believe that the ASEAN may grow into China's raw-materials appendage (parallels with Russia are obvious), while the past and the present may develop into an uneven distribution of the future growth-based gains between Chinese minorities and local populations. Meanwhile the diaspora will perform their comprador functions not so much for the Western but for Chinese companies [15]. At that, Beijing might use its stronger ties with its diaspora as leverage on economic and political processes in these host countries, which actually coincides with Russian worries about Chinese demographic expansion.

The potential for an economic dependence of ASEAN states on the PRC definitely exists, given the structure of their trade and economic relationships, as well as in their inevitably closer economic cooperation. However, irrespective of prospects for rapprochement, the share of the diaspora's capital in the overall national businesses will definitely grow, discrimination towards the Chinese is sure to abate, and the Chinese will inevitably expand their participation in host country politics. Consequently, a stronger diaspora will step up competition with the locals, as well as their export of capital to the PRC.

However, the resultant gains for the Southeast Asians from Chinese diaspora activities will significantly exceed the damage done.

While this forecast appears to be sufficient for drawing a line, there is one more aspect of direct relevance for Russia.

An Example for Russia?

Could the above model of “a large diaspora as a boost for economic development” offer an instructive example for Russia? Does not it seem rational to attract hordes of diligent and unpretentious subjects of the Heavenly Empire and thus help Russia's ailing economy, especially since Beijing is interested in exporting labor and since 2002 has been suggesting that the SCO countries establish the free exchange of goods and services? The potential drawbacks of the Chinese presence could be settled by the development of a climate of mutual understanding between these two strategic partners…

The answer is definitely NO. For historical reasons, Russian society is not ready to receive any large groups of migrants since it severely suffers from a migrant-phobia to which can only be overcome by much time and resources. Suffice to say that the dislike of migrants to a great extent reflects the loss of international positions previously held by the Soviet Union. Besides, Russia's economy cannot effectively employ the skills and capitals of both medium and large businesses due to the adverse investment climate. Russia cannot attract skilled Chinese migrants because it is unable to offer them an adequate quality of life. Unfortunately, Russia's natural immigration contingent is bound to be limited to unskilled labor, which is the dominant situation today.

1. See: Li Qi-rong. Cooperation, Mutuial Benefit and Development on Capital of Southeast Asian Overseas Chinese in Change of Sino-Southeast Asia Relationship.

2. Long Dawei, Zhang Hongyuan, Deng Gao. Cong yuanbian zou xiang zhu liu [From Marginals to the Mainstream] Huaqiao huaren lishi yanjiu (Beijing). 2011. Issue 2. P. 7

3. Hai wai huaren yu guoji yimin yanjiu // hai wai huaren yanjiu lun ji / He shiyuan zhubian [The Study of Chinese Abroad and International Migration // A Collection of Papers on the Study of Chinese Abroad / Editor-in-Chief He Shiyuan]. Beijing, 2002. P. 7.

4. The China Infortmation Technology Handbook / Ed. P. O.de Pablos, M. D. Lytras. N.Y: Springer Science, Business Media. 2009. P. 206

5. See the often republished fundamental work: Haley, George T. ; Tan, Chin Tiong, and Haley, Usha C. V. New Asian Emperors. The Overseas Chinese, Their Strategies and Competitive Advantages

Butterworth Heinemann, 1998; Also see: Chuan Ren. Hai Wai huaren de liliang. Yimin de lishi he xiankuang [The Power of Chinese Abroad. History and Current Status of Emigrants]. Bejing.: Shijie zjhishi chubanshe. 2007

6. This version of periodization is not the only one and has been suggested by: Zhuang Guotu, Wang Wangbo. Migration and Trade: The Role of Overseas Chinese in Economic Relations between China and Southeast Asia / International Journal of China Studies. V. 1, # 1, January 2010, P. 175–176

7. ASEAN Foreign Direct Investment Statistics www.asean.org/news/item/foreign-direct-investment-statisticss

8. OECD data for key basic countries: www.oecd.org/dev/aseancountriesreturningtopre-crisisgrowth.htm

9. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-07/23/c_132566755.htm

10. ASEAN External Trade Statistics. Trade 2011–2012. www.asean.org/images/2013/resources/statistics/external_trade/2013/table17.pdf

11. ASEAN Statistics. Selected key basic ASEAN indicators. www.asean.org/images/2013/resources/statistics/SKI/table1.pdf

12. ASEAN Community in Figures. 2009. www.aseansec.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ACIF2009.pdf

13. Qiu Yuanping. Shijie huashang dahui lianjie Zhongguo yu shijie jingji fazhan. (The World Chinese Enterpreneurs Convention Connects China with Development of Global Economy) URL: http//www.chinanews.com/zgqi/2013/09-26/5327408.shtml

14. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-07/23/c_132566755.htm. According to official Chinese statisics, in 2010 FDI from foreign-based Chinese (mostly to Southeast Asia) into China's economy was USD 77 billion. See: Zhongguo tongji nianjian (China's Statistics Yearbook). 2010. Tables 6–14. URL: www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2010/indexce.htm

15. Linda Y.C. Lim. Southeast Asian Chinese business and regional economic development // Routlrdge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora / Tan Chee-Beng ed. L., N.Y. 2013. P. 256 – 260

(votes: 2, rating: 4.5) |

(2 votes) |