Vladimir Putin’s unexpected U-turn on the construction of the South Stream pipeline is without a doubt a major game changer. The European Union stands to lose the most from the move. By itself, however, redirecting the pipeline through Turkey rather than Bulgaria does not strengthen Russia’s position on the European gas market from a strategic point of view. Rather, abandoning the South Stream project should be a good reason to start a new chapter in energy cooperation between Europe and Russia.

Vladimir Putin’s unexpected U-turn on the construction of the South Stream pipeline is without a doubt a major game changer. The significance and political severity of this step was cemented by the time and place of the decision – following talks with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Ankara, at the height of the confrontation with the West over the crisis in Ukraine. The European Union stands to lose the most from the move. By itself, however, redirecting the pipeline through Turkey rather than Bulgaria does not strengthen Russia’s position on the European gas market from a strategic point of view. Rather, abandoning the South Stream project should be a good reason to start a new chapter in energy cooperation between Europe and Russia.

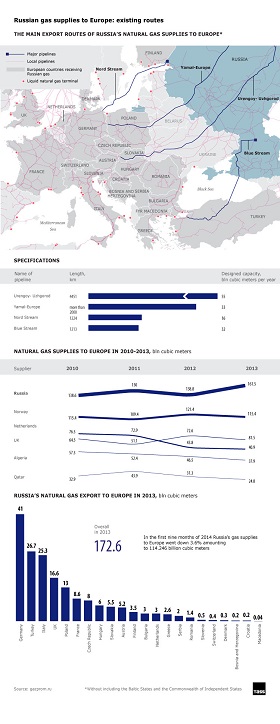

The decision on South Stream can easily be viewed as a reaction to Western sanctions. For years, Brussels has been pursuing an active policy against Russian plans to build a southern link of its gas infrastructure to connect the country directly with the European market, bypassing transit countries, primarily Ukraine. The northern part of this system, Nord Stream, is already up and running, albeit with certain restrictions imposed by the European Commission. Gazprom had envisioned the Nord and South streams as becoming a stable infrastructural system in the strategic partnership between Russia (the main supplier) and Europe (the main consumer), without the need for transit countries. But the idea did not garner much support from the European side, especially for the southern part. The main stumbling block is that the project did not – and does not – conform to the standards of the Third Energy Package ratified by the European Commission’s Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators with regard to European Union and third party states. More specifically, the European side was not satisfied with Russia’s unwillingness to allow other suppliers to use the project’s infrastructure, and the fact that Gazprom would be the main operator. All this despite the fact that Brussels had no qualms about making such demands while offering no financing of its own whatsoever. Russia had teamed up with a number of private European investors to front around $15 billion. Yet, according to the logic of European officials, it still had to allow other gas producers access to its infrastructure. In other words, Europe, having invested not a single cent in the project, would have received a free channel for the delivery of natural gas as well as an instrument to apply pressure on Russia. Now that the situation has changed, the reaction of European officials, particularly those in Bulgaria who had for years played Russia, the European Union and the United States off against each other for their own gain, shows that this outcome was at the very least unexpected.

Another matter entirely is Russia’s relations with its European partners in the project – Serbia, Hungary, Austria and Italy, as well as its relations with partner companies. Judging by the official reactions of government representatives of these countries, they had been given no prior notice about the suspension of work on the South Stream project. Serious negotiations now lie ahead. The fact of the matter is that moving the construction of the main part of the pipeline to Turkey does not automatically mean that gas will be supplied to these countries. This is because, according to the new strategy, Russia will build pipelines up to EU borders only, with the might-have-been partners having to pick up the financial slack and invest heavily in the construction of additional pipelines.

The undisputed winner in the entire affair is Turkey, which had for years dreamt about – and is successfully putting into practice – becoming a strategic hub for supplying energy to Europe from the Middle East. And now, it would seem, from Russia as well.

On the whole, Russia turning its back on the expensive and politically risky project is an undoubted benefit, even if significant investments have already been made in ground infrastructure which, according to Gazprom head Alexey Miller, amount to some €4.6 billion. The gas pipeline is, of course, extremely expensive, with an estimated value of €15 billion; although some analysts put that figure at €25 billion, with huge potential for supplying gas. The distance between Dzhubga in Russia and the Austrian hub of Baumgarten alone is 2,200 kilometres, making the delivery of natural gas along this route far too expensive for the consumer.

The political risks for the project in its original form were too high. Even the economically efficient Baltic Nord Stream mentioned earlier, which focuses on the main consumer of Russian gas (Germany), is still not running at full capacity against the backdrop of the real threat to the continued operation of Ukraine’s gas transmission network

At the same time, as I have already mentioned, Russia placing all its eggs in the Turkish basket has its own risks. To begin with, Ankara has its own idea about its role and place in the development of energy flows in the region. That is, in place of the politically and economically volatile Ukraine as a transit partner, Russia is getting a country that is well aware of its bargaining power. Secondly, the experience of the Blue Stream project has taught us that Turkey could at any time turn against Russia if it is beneficial to the country politically and economically. Thirdly, we should not forget that construction of the ambitious Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) project, which will transport gas from the second phase of the Shah Deniz gas field off the coast of Azerbaijan through Turkey to Europe, is currently under way. Although the volume of gas to be delivered via this pipeline is miniscule compared to the expected gas flow from Russia (the first phase of the project will supply Europe with 10 billion cubic metres of Azerbaijani gas), the completion dates for both projects (2018–2020) are extremely close. This adds a sense of urgency to the fight for consumers in the southern EU countries. Put simply, in the medium term Turkey will control both Russian and Azerbaijani – and soon Iranian and Iraqi – gas flows. In this context, entrusting Turkey to control the redistribution gas supplies would seem inadvisable.

With regards to the agreement to lay the pipeline through Turkey, Russia needs to take measures to protect itself in the event that relations with its new partner take a turn for the worse. In order to do this it is necessary in the nearest future to:

– Launch a new round of negotiations with the European Commission with the aim of receiving permission to run Nord Stream at full capacity and use European infrastructure to supply gas to the European Union.

– Explore the possibility of increasing the capacity of the Belarusian arm of gas supplies to the European Union, to reduce Russia’s reliance on Ukraine as a transit country.

– Consider using LNG as an alternative channel for supplying the European Union with Russian gas. The extensive network regasification terminals in Europe would allow Russia to activate its LNG projects (particularly the Yamal project) without having to make major investments in pipeline infrastructure. The work could be coordinated by the Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation, in order to avoid competition between Russian suppliers.

– Get the Russian–Azerbaijani dialogue on the right track, on the one hand, to strengthen its negotiating position with Turkey on the other. The aim of these efforts should be to coordinate efforts to enter the southern European gas markets, which will avoid competition for consumers.

The full or partial implementation of these measures will allow Russia to create a balanced and diversified system of natural gas supply routes to Europe that is resistant to crises and the political machinations of transit countries. The strained relations between Russia and the European Union make it difficult to talk about the prospects of entering into comprehensive negotiations on the creation of a contractual framework for cooperation in the energy sector. But sooner or later the question will nevertheless be raised, since Russia will remain at least one of the main suppliers of natural resources to the European Union in the long term. Similarly, the European market will remain a priority for Russian companies, even as the path to China has officially opened up.