The Deepening UK-EU Crisis

David Cameron and Angela Merkel,

Berlin, November 2011

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of History, Professor at MGIMO-University

After just one year in power, the British coalition government was forced to deal with a harsh EU-wide crisis focused around the Eurozone, one which called the latter's very survival into question. London’s behavior, and the steps it took to overcome the crisis, show that the British take a different stance to their continental partners. The key seems to lie in understanding the fundamentals of the ruling coalition’s EU policy, given that that the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats drastically differ in their approaches.

After just one year in power, the British coalition government was forced to deal with a harsh EU-wide crisis focused around the Eurozone, one which called the latter's very survival into question. This time, bankruptcy seemed to be in store not only for banks but also for entire countries, in particular Greece, Spain and Italy. London’s behavior, and the steps it took to overcome the crisis, show that the British take a different stance to their continental partners. The key seems to lie in understanding the fundamentals of the ruling coalition’s EU policy, given that that the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats drastically differ in their approaches.

The Tories and Europe

On the eve of the 2010 elections, the Conservatives presented themselves as a moderately Eurosceptic party, interested in EU membership but disinclined to participate in major integration efforts. Specifically, this applied to the Economic and Monetary Union, as well as to the extension of EU authority to judiciary, social, domestic, foreign and security policies. The 2010 Conservative election manifesto accentuated the protection of national interests, emphasizing that the populace must have a say in any further handover of prerogatives to EU bodies - the so-called Referendum Lock. The country was promised a referendum on transition to the euro, though Tory leaders and documents insist that this in any case will not take place under a Conservative government: “We will never take Britain into the Euro”. More than that, the Conservatives desire the return of certain judicial, criminal justice and social legislation powers transferred to Brussels by the previous Labour government, as well as the abrogation of the Human Rights Act (which in 1998 incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into British law) in the name of improving counter-terrorism and anti-crime measures. Overall, the European Union remains a major, but far from only, foreign policy priority of the Tories, whose slogan is “we want to be part of Europe, not governed by Europe.”

The Liberal Democrats and Europe

.jpg)

Liberal Democrats want Britain to

join the Eurozone when "appropriate economic

conditions" arise.

The Liberal Democrats are Britain's most pro-European party, ranking relations with the European Union as their top foreign policy priority. Their 2010 election manifesto insists on closer cooperation with the EU for job creation, tighter international regulation in banking and finance, reform of the common agricultural and budget policies, establishment of an asylum system, and reorientation to a green economy.

Bearing in mind the flaws in the EU mechanism, the party has come out for raising the efficiency of European institutions and their responsibility to the EU peoples, curbing Brussels extravagance, and retaining Britain within the international counter-crime system (Europol, Eurojust and European Criminal Records Information System), etc.

The Liberal Democrats do not oppose a referendum on Britain's membership in the European Union if "fundamental changes in relations between Britain and the EU" need to be discussed. They support developing a common EU foreign policy that should, as they see it, strengthen relations with China, Russia and other countries, and step up participation in Arab-Israeli conflict settlement. In addition, the Liberal Democrats want Britain to join the Eurozone when "appropriate economic conditions" arise (and not right now, because of the Eurozone crisis) and if the people approve the idea via referendum.

Coalition Policy Toward the EU

On the eve of the 2010 elections, the Conservatives presented themselves as a moderately Eurosceptic party, interested in EU membership but disinclined to participate in major integration efforts.

The ruling coalition's EU policy is the product of compromise. The Liberal Democrats had to give up the transfer of more British powers to Brussels. For the sake of the coalition, the Conservative leaders were at first non-confrontational, and inclined to refrain from demands to return powers to Britain. However, they soon fell under Eurosceptic influence and toughened their stance. The coalition's document "The Coalition: Our Programme for Government" contained an agreement to forego participation in the establishment of the European Public Prosecutor. As for other criminal law measures, the approach was to consider them "on a case-by-case basis, with a view to maximising our country’s security, protecting Britain's civil liberties and preserving the integrity of [Britain's] criminal justice system."

Although the Tories secured all key foreign policy posts, the Liberal Democrats were quite happy to see the Minister of Europe position held by pragmatic David Lidington instead of Eurosceptic Mark François. David Cameron positioned himself as a moderate Eurosceptic, "practical and reasonable". Later, just like other Tory leaders, he hardened his stance under societal and party influence.

The Eurozone in Crisis and the Deepening London-Brussels Controversy

The Eurozone troubles have worsened relations between Britain and its European partners, with London definitely interested in a stable euro but unhappy about the ways out offered by Brussels. Britain has declined to support steps taken by Belgium, France, Italy and Spain against speculation. The logic of battling the crisis forced EU unity and common financial operations rules, leading toward a genuine financial union.

Preparation for the Eurozone emergency summit in August 2011 exposed profound differences between countries in their approaches to recovery. On May 11, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne spoke in Parliament to justify the coalition's austerity measures, underlining that they have turned the country into a "safe haven in the global debt storm". During that period, he publicly accepted the establishment of a fiscal union as the only response to the Eurozone crisis, while simultaneously emphasizing the need to defend national interests. Britain did not rule out the possibility of Eurozone breakup, and followed some other EU countries in devising contingency plans.

The country was anxious about restoration of the French-German tandem, which had defined the direction and velocity of the integration process, but visibly weakened during the EU's eastward expansion. The duo's might became obvious at the EU Paris summit in August 2011, when France and Germany managed to work out a common line and offer the other 15 Eurozone countries a stabilization program. In essence, the issue was the so-called "economic government", headed by President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy and intended to produce a common taxation policy for the Eurozone. London fears that such a step will be inevitably followed by a common economy and common finance and economy ministers. There was also a proposal to expand the constitutions of member-states with provisions on the budget revenue-and-expenditure ratio, as well as on regular Eurozone summits to coordinate macroeconomic policies. Britain rejected measures aimed at tightening the Economic and Monetary Union. Reflecting the Eurosceptic perspective, some British media, including the Daily Mail, have begun to speak of the coming of a "Fourth Reich", hinting that Germany, Europe's largest economy, is going to dictate policy to its partners. They observe that, in contrast to Hitler's times, Germany would not have to use military force, as it can conquer Europe with the aid of economic and financial levers.

During the past two years, Berlin's domination in the French-German tandem and its political influence have been progressively mounting, especially after Nicolas Sarcozy left the arena. The Financial Times even called Berlin "the capital of Europe", despite the fact that the EU's main bodies sit in other cities and Chancellor Merkel has to attend summits in Brussels, and does so to seek compromises. At the same time, all the key decisions are taken in Berlin, and the Eurozone crisis has only accelerated the process [1].

The Eurozone troubles have worsened relations between Britain and its European partners, with London definitely interested in a stable euro but unhappy about the ways out offered by Brussels.

The prospect of a common "economic government" for the Eurozone does not suit Britain, as the step would de facto push it to the margin, into the company of Poland, Sweden and other non-Eurozone countries. In the absence of a need to look to London, the strengthened French-German duo will be able to step up intra-Eurozone integration. Facing the menace of the European Union growing into a multi-tiered structure and establishing of a federative Europe governed by Berlin, some prominent British analysts, for example Anatole Kaletsky of The Times, have tumbled to an obviously utopian scheme for the Eurozone's salvation, namely. breaking France's special relationship with Germany and the latter's withdrawal from the zone.

The threat of Britain's marginalization within the EU was confirmed at the Brussels summits on October 23 and 26, 2011, which gave rise to the "two-speed Europe", with the "economic nucleus" of the 17 Eurozone countries on the one hand, and the 10 other members with reduced influence on economic decisions on the other. The British were wary that the rescue plan had been produced without the non-Eurozone states, which had simply been requested to leave the conference. As a result, the two-speed Europe (a possibility admitted by the Conservatives back in mid-1990s) [2] became a reality. The new balance of forces in the EU became clear in the open debate between David Cameron and Nicolas Sarcozy on October 23, when the latter emphatically rejected Britain's demands to participate in Eurozone sessions. The British Prime Minister has so far failed to build a non-Eurozone coalition out of the excluded countries (Hungary, Denmark, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Sweden) because seven of them (the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania and Hungary) have pledged to join the Eurozone, undermining London's efforts to counterbalance the group of 17 with another potent coalition that it would have to reckon with. Moreover, Britain risks remaining all alone, as was seen at the January 2012 EU emergency summit when the Budget Pact was first vetoed by London but then adopted within the Eurozone with participation of the other union members. Voted against only by Britain and the Czech Republic, the Pact has set a new rigid budget discipline (with the deficit limited to 0.5 percent of national GDP).

Some British media have begun to speak of the coming of a "Fourth Reich", hinting that Germany, Europe's largest economy, is going to dictate policy to its partners.

London demanded the protection of British companies and banks from European financial oversight in order secure the City’s role in global finance. At the EU summit in December 2012, Cameron confirmed Britain’s intention to stay out of the Banking Union (alongside Czech Republic and Sweden). London is also anxious about German preparations for EU-wide labor market reform, as well as plans to bolster the European Parliament, in particular the inter-institutional agreement on better coordination between the EU Council, European Commission and European Parliament in anti-crisis efforts.

In summer 2011, the British Parliament adopted its Referendum Lock act, which envisions prior popular approval of power transfer from London to Brussels, including transition to the euro, participation in the establishment of the European Public Prosecutor system, removal of border controls, social policy and issues related to European financial and social security, and foreign policy and security affairs.

The British Veto

In autumn 2012, Britain threatened to use its veto during the discussions of the EU’s seven-year budget [3]. Opposing Berlin, London insisted on freezing expenditures. Back in December 2010, British and German leaders agreed to limit the EU budget growth to the inflation rate. Contrary to the accord, the European Commission insisted on increasing spending by almost five percent, which meant a considerably higher contribution from Britain in 2014-2020 (currently £10 billion). Cameron announced “I have not put in place tough settlements in Britain in order to go to Brussels and sign up to big increases in European spending.” [4] London’s stance virtually deprived East European countries of substantial assistance from Brussels. Van Rompuy responded by threatening to take away Britain's compensation under the so-called "British cheque" scheme [3] (according to which, since 1984 Britain has been given back 66 percent of the difference between its contribution to the EU budget and payments out of the amount). In its turn, Germany threatened to call off the November summit, although later Berlin denied doing so [1].

Cameron announced “I have not put in place tough

settlements in Britain in order to go to Brussels

and sign up to big increases in

European spending.”

Nevertheless, the summit took place on November 23, 2012, but no mutually acceptable decision was found. Britain was pleased by the support of Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and Denmark. The summit also revealed Germany’s alienation from its traditional partner France (due to François Hollande’s ascent to presidency) and its increasing sympathy with Britain regarding the restriction of Brussels's appetite. The European media responded by switching the coalition label from Mercozy to Merkeron.

Complications in relations with EU with partners gave a boost to Euroscepticism in the UK. According to a Daily Mail December 2011 poll, Cameron’s tough attitude towards the EU received 62 percent approval, while about 50 percent insisted on EU withdrawal. The Brits, especially within the Conservative Party ranks, increasingly tend to demand a new format for relations with the European Union, which drives Tory leaders to Thatcherism. During a visit to Germany in October 2012, Foreign Secretary William Hague announced London’s intention to retrieve some of the powers it had delegated to Brussels, and laid out he British approach to the minimization-oriented EU reform: the Union should primarily be a common market with several collective political goals, for example restraint of Iran’s nuclear program. Thus, the British are true to themselves, as they have always, even before joining the EEC, been consistent in the drive to harmonization and coordination in foreign affairs. Meanwhile, numerous differences on international issues during the past decade, including the split of Europe into the new and old segments during the Iraq crisis, do underline the difficulty of this aspiration. Hague also doubted the need for further EU centralization and budget expansion.

London and EU Expansion

Britain’s approach to the expansion of the European Union remains unchanged. It was supported both by the Conservative government of John Major and the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, proceeding from the point that a larger EU would have more global clout. But the key calculation was that EU expansion paid for by the European Free Trade Association, and later by East European countries, would stall deeper integration. London believed that the newcomers would need a lot of time to adapt, and would not soon be able to participate in the most fundamental formats of integration, for example by joining the common currency, and that this would slow the process. For this reason, Britain welcomes the inclusion of Iceland, Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey and other countries. However, London seems to have fallen into its own trap, as its appeals for expansion unwillingly brought the Eurozone crisis closer, ultimately affecting Britain by weakening its influence and pushing the country to Europe’s periphery.

Nevertheless, taking account of growing Euroscepticism, the Conservative approach to the EU has remained intact, i.e. Britain will refrain from fresh integration efforts, is willing to preserve its national currency and is not ready to trade access to Eurozone decision-making for infringement of its parliamentary sovereignty (while members of the budget and tax union will have to give away their control of the national budget process and become subject to European Commission examination). Moreover, the Cameron intends to regain some of the national sovereignty given up by the Labour government, i.e. to withdraw from certain domestic programs (crime control, the universal arrest mandate) and legal norms, for example for the labor market (rejection of the 48-hour week). In 2013, Britain will also secede from the European Financial Stability Facility that it had joined under the Labour in May 2010 [5]. In December 2011, London refused to contribute its 30 billion euro share to the IMF for the purpose of countering the Eurozone crisis.

In summer 2012, Cameron's government launched a sort of audit for Britain’s participation in the EU: prior to the next parliamentary elections, 32 reports are to be prepared, six of them to be made public in summer 2013 [1]. Agreed upon during the creation of the coalition, the research should not offer outright recommendations to the government, but some assessments will be critical in nature, with consequences to be expected for Britain's participation in certain programs. Conservative dissenters in Parliament already demand a free hand in such areas as immigration, human rights, refusal to fulfill the EU’s 130 crime control norms, etc.

The Promise of a Referendum

In order to subdue intra-party criticism and respond to the demand of one hundred Tory MPs to hold a referendum on EU membership, in summer 2012 Cameron seconded the idea. [6] In February 2013, he repeated the proposal, at the same time expressing hope that Britain would not withdraw because the EU can still restore British trust through reforms. However, a promise is not the same as its fulfilment, and Cameron has made Conservative victory at the June 2015 elections a precondition for the referendum. Only after that, and after negotiations with European partners, is the Tory government going to hold a national referendum on withdrawing or staying (the latter on new conditions negotiated by the government). The prime minister has suggested either a new treaty with participation from all EU countries, or a separate agreement which would increase Britain's powers.

Neither the Tories nor Labour, to say nothing of the Liberal Democrats, want to withdraw from the European Union, as it will inevitably undermine British influence in Europe and the wider world. Irrespective of party affiliation the government is likely to avoid a referendum that the British might later regret.

The Liberal Democrats see little appeal in the idea of a referendum, and it can only undermine relations within the ruling coalition. As for Cameron, he was eager to pacify the Tory Eurosceptics who have closed their ranks and threaten their leader with early resignation. In October 2011, they already proposed a resolution in the House of Commons to demand a referendum on EU membership. The move was voted down because the Labour opposition and the Liberal Democrats supported the government (483 votes against 111). However, 81 Conservatives and 16 Liberal Democrats opposed their leaders and voted for the resolution, exposing the deepening party split. [7] Some Conservatives may defect to the anti-EU United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which is gaining strength, demonstrating visible success in the European Parliament and local elections; this May, UKIP received 25 percent of the vote at local elections, overtaking the Tories and rising to second position in some districts –The Times, May 4, 2013. According to some observers, at the 2010 parliamentary elections, UKIP stole 40 Tory seats in the Commons [8], which triggered an intra-party discussion on a possible agreement with UKIP before the next elections on providing its leader Nigel Farage with a cabinet post in the Tory government. The prime minister is forced to operate as if in a minefield, constantly keeping an eye on his coalition partners and on Conservative right-wingers.

Cameron believes that the referendum idea will help the Tories win the next parliamentary elections, and their ratings are indeed rising with popularity of the proposed new relationship with the EU. At the same time, Eurosceptics cannot relax, as there have been many unfulfilled referendum promises, i.e. on the European Constitution and the Treaty of Lisbon.

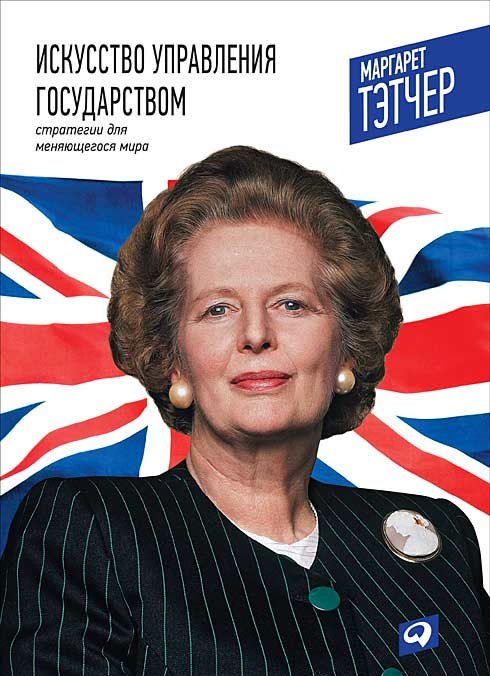

Thatcher’s proposals to withdraw from the EU

in her political will, Statecraft: Strategies for a

Changing World, where she explicitly said

that they should drop out of the EU.

Cameron's referendum proposal appears to be a form of blackmail of the EU – return some of our powers, or we are out. London expects this "boogieman" to work as it did in 1974-1975, when the threat of a referendum helped the Wilson government review the terms of EEC membership in Britain's favor. After the 1975 talks, the referendum was held and demonstrated a 67-percent majority for EEC membership [9]. While the British proposal enjoyed the support of the moderately Eurosceptic Czech Republic and Finland, Washington showed concern as the withdrawal of America's closest ally from the EU would lessen its influence in Europe. Germany is also keen to keep the UK in, as Merkel has already indicated possible concessions to Britain if the demands are moderate and London refrains from vetoing decisions on Eurozone recovery.

Thus, in its speech Britain is quite close to Baroness Thatcher’s proposals to withdraw from the EU in her political will, Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World [10], where she explicitly said that the British should give up their delusional belief that they can halt the European locomotive moving towards the creation of a super-state, and that they should drop out of the EU. In those days, the party found her approaches repugnant and distanced itself from the ex-premier. After one more round under John Major, the Tories are facing an inevitable weakening of British influence in the EU at the new stage of integration, and now return to Thatcherism, i.e. the "foundations of conservatism".

In fact, neither the Tories nor Labour, to say nothing of the Liberal Democrats, want to withdraw from the European Union, as it will inevitably undermine British influence in Europe and the wider world. Irrespective of party affiliation (and a Tory victory at the next elections seems rather improbable), the government is likely to avoid a referendum that the British might later regret.

The mounting differences with EU partners on basic issues related to London's unwillingness to give away more of its sovereignty, and the trend toward its marginalization in the "multi-speed" European environment, push Britain to attempt to once again compensate for its loss of influence through links beyond the European Union, including such BRICS states as China, India and Russia. Such a move might advance Russian-British commercial, economic and possibly political ties. However, it seems hasty to expect major positive changes in the political field in the short-term, not least given the extraordinary sensitivity of the British public regarding the Litvinenko case.

1.The Financial Times, 2012, 23.10.

2. N.K. Kapitonova. Foreign Policy Priorities of Britain (1990–1997). Moscow, 1999. P. 83.

3.The Independent on Sunday, 2012, 28.10.

4.Daily Mail, 2012, 23.10.

5.Keesing’s Record of World Events. 2012. Vol.58.№ 9. P.52235.

6.The Financial Times, 2012, 02.07.

7.Keesing’s Record of World Events. 2011. Vol. 57. № 10. P. 50716.

8.Daily Mail, 2012, 29.12.

9.Politics UK. 7th Ed. 2011.P. 619.

10.Margaret Thatcher. Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World. HarperCollins Publishers, 2002.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |