The Fight for Nord Stream 2: The Interests of all the Players Involved

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 4, rating: 5) |

(4 votes) |

Professor at Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, and leading expert at the National Energy Security Fund

News about the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline can be heard almost every day. In reality, the project is one of the primary areas in Russia’s fight against the United States. Washington has been critical of major Russian infrastructure projects in the past, but the situation was different from the one we are witnessing today.

It is not financially viable for exporters of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) to deliver to Europe, as the prices are higher on alternative markets. In order to support American gas producers, the U.S. authorities are trying to clear the market of competition for them, specifically targeting Gazprom’s positions in Europe.

It can thus be said that the attacks on Nord Stream 2 are based on the desire of the United States to reduce the share of Russian gas on the European market, which will lead to a shortage and, consequently, higher prices.

The United States is using Poland, as well as Sweden and Denmark, to exert pressure on Russia and Nord Stream 2.

Ostensibly, the United States is using a two-level model of counteracting Nord Stream 2. The first part involves putting pressure on the project via third parties. This is followed by direct pressure.

News about the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline can be heard almost every day, like reports from the front lines. In reality, the project is one of the primary areas in Russia’s fight against the United States. Washington has been critical of major Russian infrastructure projects in the past. The original Nord Stream came under strong criticism, and a 2014 visit of U.S. senators to Bulgaria was soon followed by the refusal of the authorities in that country to go ahead with the Gazprom project to build South Stream on its territory. Even earlier, the U.S. Department of State created the post of United States Special Envoy for Eurasian Energy (in the Caspian region), originally occupied by Clayland Boyden Gray (2008–2009), and then by Richard L. Morningstar (2009–2012).

In order to support American gas producers, the U.S. authorities are trying to clear the market of competition for them, specifically targeting Gazprom’s positions in Europe

However, the situation back then was different from the one we are witnessing today. To begin with, there was not the background of fierce opposition between the United States and Russia that there is today. This has been caused by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and Moscow’s fiercely independent stance with regard to the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria. Second, significant changes have taken place on the global gas markets on recent years, with the United States turning from an importer of gas into an exporter of gas. This fact is extremely important for understanding the American position on Nord Stream 2. It would appear that, in the history of the West’s countermeasures against Russia, there has always been a “surface” element and an element that is “under the water,” as it were, like an iceberg. And it is this unseen element that is crucial to understand the processes taking place.

Why the United States Opposes Nord Stream 2

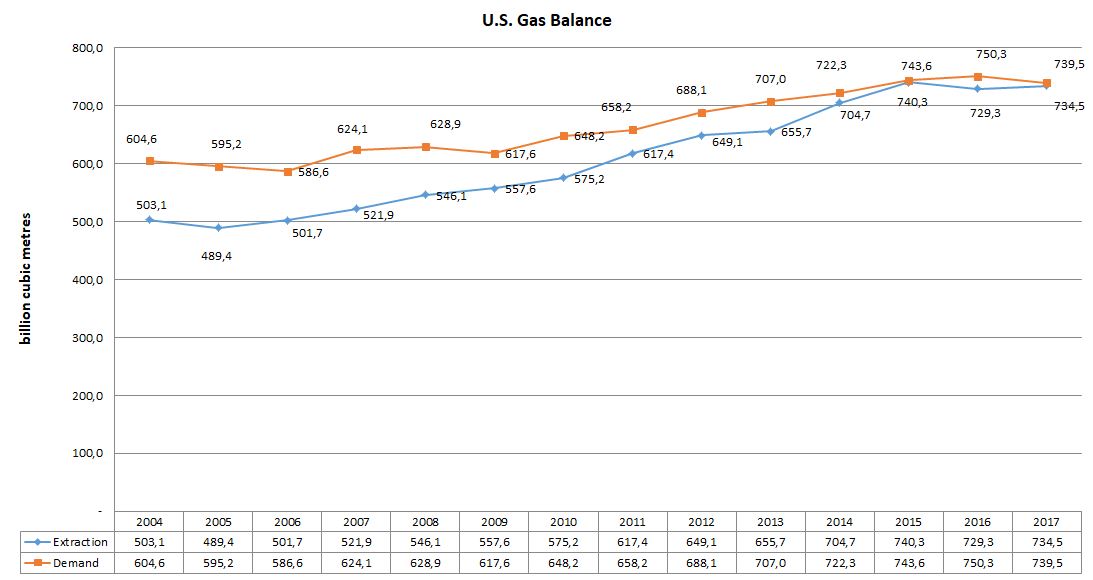

The so-called “shale revolution” in the United States in the early 2000s helped the country increase its gas production. According to BP, gas production in the United States grew from 489.4 billion cubic metres in 2005 to 734.5 billion cubic metres in 2017.

Source: Statistical Review of World Energy

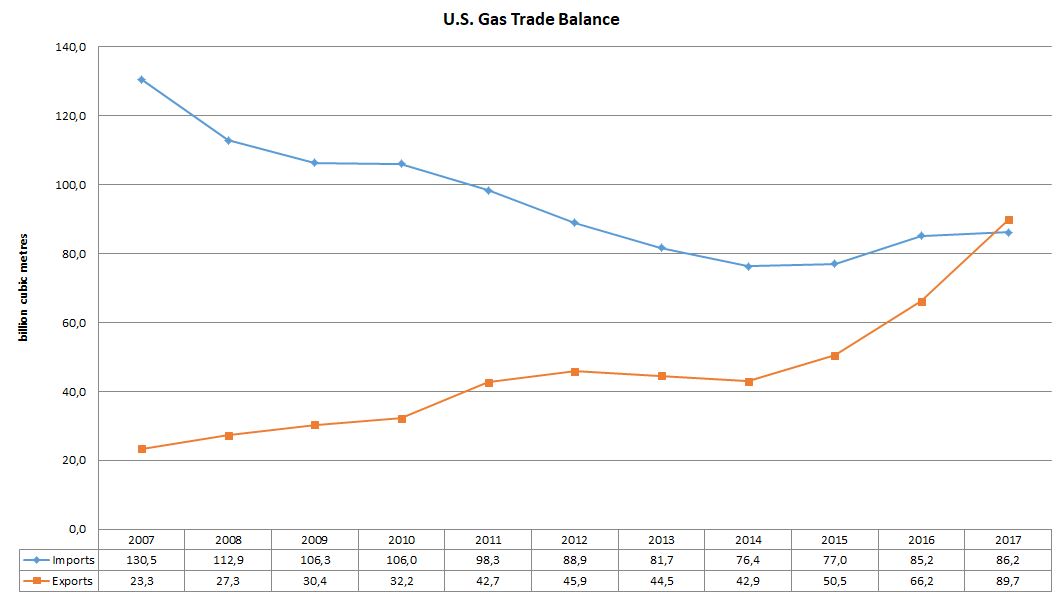

A similar trend has been recorded by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), which notes that gas production in the country increased from 18 billion cubic feet (511 cubic metres) in 2005 to 26.9 billion cubic feet (760.6 billion cubic metres) in 2017. The surplus of gas on the domestic market allowed the United States to launch LNG exports in 2016. The country did not become a net exporter of gas until 2017, however, with large-scale import and export operations being carried out with Mexico and Canada.

Source: EIA

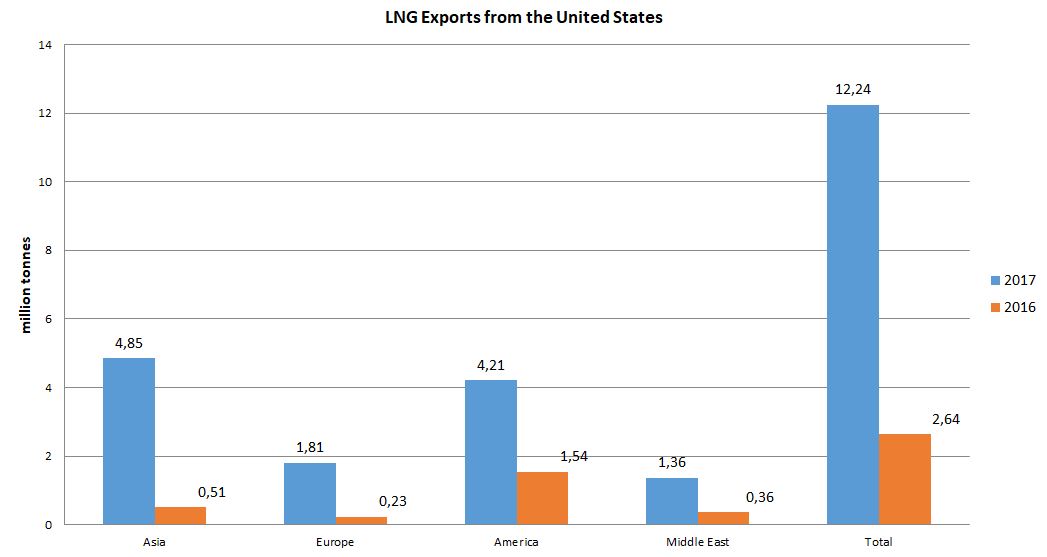

Latin American countries were the main importers of LNG in 2016, but were replaced in 2017 by Asian buyers.

Source: International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers (GIIGNL)

It is not financially viable for exporters of U.S. LNG to deliver to Europe, as the prices are higher on alternative markets. It is important to remember that there are no state companies in the United States, so the government cannot issue a directive to deliver LNG to Europe. Furthermore, the structure of exports is such that U.S. companies are in fact selling international traders the opportunity to liquify gas, and they are deciding for themselves whether or not to produce the LNG and which market to send it to. Naturally, they are sending LNG where they can get the biggest possible margin in a specified period of time. Gas markets are still regional in nature, with significant differences in prices between Europe and Asia, for example.

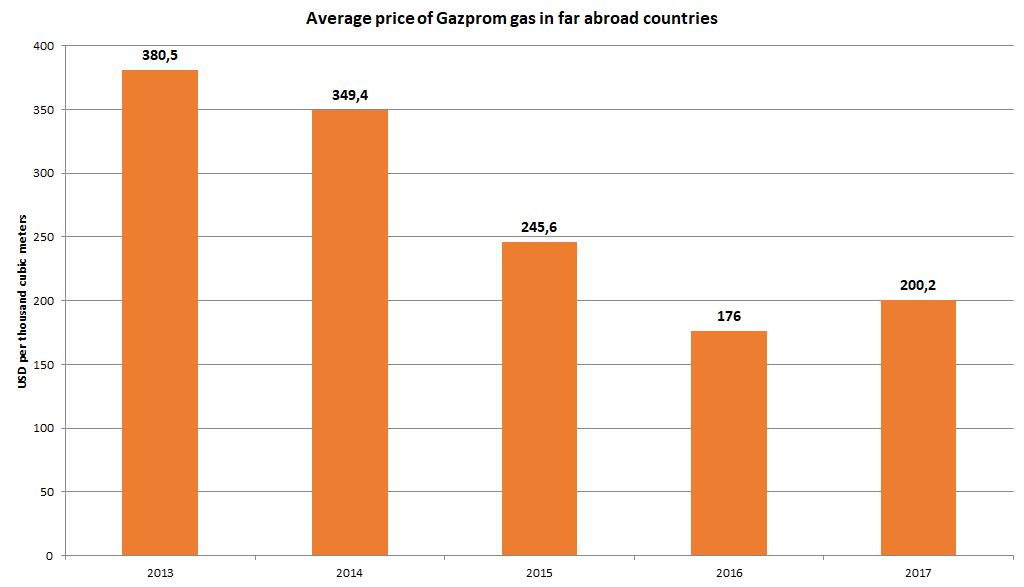

Gazprom is strengthening its positions on the European markets, selling the majority of its gas on long-term contracts that are linked to oil prices. The fall in oil prices from $98.90 in 2014 to $43.70 in 2016 meant that gas prices for European consumers also dropped during that period.

Source: Factbook Gazprom in Figures, 2013–2017

Low prices have constituted a competitive advantage for Gazprom, helping the company achieve record numbers in terms of the volume of gas supplied to Europe (including Turkey) in 2017 – 194.4 billion cubic metres. Meanwhile, the United States delivered just 2.75 billion cubic metres to Europe during the same period.

This difference poses a risk both for Nord Stream 2 and for Russian gas exports to Europe as a whole. The United States hopes to increase LNG exports and become the main supplier of liquefied natural gas to the global market. There is information that U.S. companies have submitted applications to the Department of Energy (DOE) for licenses to export LNG produced at their plants, the total capacity of which amounts to approx. 383 million tonnes per year. However, given the current state of affairs on the markets, the gas will go largely unclaimed. On the one hand, there is nowhere for the gas to be used. On the other, a number of these projects will simply not be profitable.

The construction of Nord Stream 2 would actually benefit Poland. The more Russian gas going to Germany, the greater the surplus of the raw material that can subsequently be traded on the spot market.

In order to support American gas producers, the U.S. authorities are trying to clear the market of competition for them, specifically targeting Gazprom’s positions in Europe. This is openly stated in Document S.1221, Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017: 115th Congress (2017–2018). The report indicates that the United States will continue to oppose Nord Stream 2; however, one of the points also says that Washington will do everything to develop the export of United States energy resources, which, in turn, will help create jobs in the country.

It can thus be said that the attacks on Nord Stream 2 are based on the desire of the United States to reduce the share of Russian gas on the European market, which will lead to a shortage and, consequently, higher prices. This will also help Washington create favourable conditions for increasing its LNG supplies to Europe. It is the creation of these conditions that will serve as the most effective tool for promoting U.S. LNG on the European market, as Gazprom has been winning the price war in recent years. It is worth mentioning here that, as oil prices rise, so too do gas prices, which thus makes the European market even more appealing for U.S. LNG suppliers. However, Gazprom is far better equipped to provide discounts in the event of an all-out war breaking out among suppliers. And sellers of liquefied gas are more likely to move on to more attractive markets than they are to become involved in the struggle for the European market by cutting their margins.

A Proxy War

Plans to create bypass pipelines around Ukraine appeared before 2014 and are thus not motivated by the desire to undermine the Ukrainian authorities.

Ostensibly, the United States is using a two-level model of counteracting Nord Stream 2. The first part involves putting pressure on the project via third parties – the main conduit of the U.S. energy policy in Europe is Poland. Warsaw has been a staunch critic of both Nord Stream 2 and Gazprom, and its arguments are politically motivated. Poland threw the first spoke in the wheel of the Russian project in 2016, when Gazprom was counting on selling 10 per cent of its shares in the Nord Stream 2 operator, Nord Stream 2 AG, to five companies – ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper and Wintershall. In order for the deal to go through, permission had to be obtained from the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection in Poland (UOKiK), as these five European companies all conduct business in that country. However, the UOKiK rejected the application submitted by Gazprom and its partners to set up a joint venture, stating that the “deal could lead to a restriction of competition.”

Poland has also tried to influence the European Commission (EC). For instance, Warsaw took the issue of expanding the provisions of the Third Energy Package to include maritime parts of gas pipelines running into the European Union. The new rules would mean that Gazprom would only be able to transport up to 50 per cent of the capacity of Nord Stream 2. It is a move designed to create unfavourable conditions for the project’s investors. Only 27.5 billion cubic metres of the originally planned 55 billion cubic metres would be transported under the project, which will cost a total of 9.5 billion euros. Evidently, Gazprom’s opponents were expecting European companies to abandon the project in light of these circumstances. However, the Council of the European Union Legal Service pointed out that expanding the provisions of the Third Energy Package to include Nord Stream 2 was impossible, as it would go against international law.

If you can prove that Nord Stream 2 is a political, rather than an economic project, then the Europeans will automatically reject it.

The Polish leadership and experts in the country often cite two mutually exclusive reasons why building Nord Stream 2 in impossible. The first reason is that the gas pipeline would lead to Gazprom having a majority stake in the European market – Russia would inflate prices and/or demand that the countries in Europe bend to its political will under the threat of cutting off the supply of gas. The second reason is that the launch of the gas pipeline will entail complete circumvention of Ukraine in terms of gas transit through the country. This would ensure that the Ukrainian budget receives no money, and the ensuing economic crisis would force the country’s leadership to again pivot towards pro-Russian policies. Another version is that Russia wants to stem the flow of money into Ukraine, so the country does not have the resources to continue the war in Donbass.

On occasion, both of these versions can be heard from politicians during a single speech. It is important to understand here that Gazprom intends to supply gas via Nord Stream 2 that it is already selling to European consumers and which does not travel through Ukraine. So, the construction of the pipeline cannot negatively impact competition on the European gas market, nor can it affect Poland in an adverse manner. This proves that the UOKiK’s rejection of Gazprom’s application to set up a joint venture was unfounded.

The construction of Nord Stream 2 would actually benefit Poland. The more Russian gas going to Germany, the greater the surplus of the raw material that can subsequently be traded on the spot market. Poland will be able to purchase the excess at favourable prices and then transfer it to German consumers, for whom gas is to be transported by the Yamal–Europe natural gas pipeline. Polish companies will be able to hold onto the same amount of gas without having to spend money pumping it to Germany. In other words, they can turn a profit by buying cheap gas on the spot market and then refusing to physically pump part of the gas to Germany.

The second theory is all not entirely correct. It is true that Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream are being built so that an alternative gas pumping route can be chosen. At present, Gazprom cannot cut the volume of gas it sends through Ukraine, as all the bypass pipelines are at maximum load. A total of 93.5 billion cubic metres of gas was transported through Ukraine in 2017. Up to 4 billion cubic metres may be transferred to Nord Stream, which has not been operating at maximum load due to the dispute over the possibility of using 100 per cent of the OPAL gas pipeline (the continuation of the line in Germany). However, the problem has been all but resolved, and Nord Stream can be expected to be running at full capacity in 2018. Another 55 billion cubic metres will leave Ukraine to be transported via Nord Stream 2, with a further 31.5 billion cubic metres to be sent through the two TurkStream lines. It turns out that, even if Russia supplies the same amount of gas that it did in 2017, then 3 billion cubic metres will not fit into the bypass pipelines, which means that Gazprom and Ukraine’s Naftogaz will have to negotiate terms for gas transit after 2019. The fact that European countries are reducing their own gas production could also create additional demand. All new gas purchases will go exclusively through the natural gas transmission system of Ukraine. If Kiev wants to hold on to its transit business, it may be worth selecting one or two of the transit pipelines and modernizing them, along with one or two underground gas storage facilities. This would mean the country would not be scattering funds, thus giving it the technical capability to provide high-quality transit services.

Instead, Naftogaz is busy reducing the profitability of the natural gas transmission system by demanding that Gazprom pay higher tariffs to transit gas through the country. Although it is more profitable for Gazprom to pump gas via Nord Stream – the tariffs are smaller, the distance to consumers is shorter, and the company owns 51 per cent of the shares in the operator of Nord Stream 1, Nord Stream AG.

However, Russia will continue to transit gas via Ukraine. Exactly how much will depend on the demand for Russian gas in Europe. In the long term, Gazprom could build new streams, for example, “Bulgarian Stream,” although there are no concrete plans for this as of yet. The second theory against Nord Stream 2 is, therefore, also false. It is worth emphasizing here that plans to create bypass pipelines around Ukraine appeared before 2014 and are thus not motivated by the desire to undermine the Ukrainian authorities.

If the application is denied, Gazprom will simply remap the route, which will not change the timeframe or costs to any significant degree.

The United States uses other countries in addition to Poland to exert pressure on the Nord Stream 2 project. Sweden and Denmark in particular have become pawns in the United States political manoeuvring, as the gas pipeline will go through their offshore areas and Gazprom has applied to these countries for construction permits. On August 25, 2016, then Vice President Joe Biden paid an official visit to Sweden, declaring that Nord Stream was a bad thing for Europe. A month later, in September 2016, the Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences published a list of scenarios of a Russian attack of Sweden. One of the scenarios suggested that Russian forces could seize the Swedish island of Gotland, with the first group of Spetsnaz forces posing as repair technicians for Nord Stream. These actions are intended to politicize the issue of building the pipeline – it is no coincidence that the idea that Russia will immediately seize Ukraine if it lays a new pipeline at the bottom of the Baltic Sea is being bandied around with increasing frequency by Polish and Ukrainian politicians. We will not dwell here on the obvious question: Why would Russia want Ukraine if its gas pipelines are empty? The point here is if you can prove that Nord Stream 2 is a political, rather than an economic project, then the Europeans will automatically reject it.

This cannot be proven in practice, however; Gazprom insists that the Europeans comply with their own laws and demonstrates the benefits of pumping gas through Nord Stream 2. And it is Ukraine that is, in fact, blackmailing the Europeans when it says that the financial burden will rest on their shoulders in the event that Gazprom fails to pay the billions of dollars per year that it is demanding to transit gas. Caught between a rock and a hard place – the United States and Germany (for which Nord Stream 2 is extremely beneficial) – Sweden has chosen to blindly execute the necessary procedures. It has reviewed the documents submitted for the presence of fire hazards and has issued a construction permit.

That the United States it attempting to block the flow of Russian gas in Ukraine, and then reduce it, which will harm European economies.

Denmark finds itself in a decidedly more complicated situation. After Gazprom submitted an application for the construction of the gas pipeline, the Danish authorities, under pressure from the United States, introduced amendments to the country’s legislation. In the past, countries reviewed applications to carry out construction in their territorial waters on the basis of the potential environmental damage of the given project, which makes it difficult to reject Gazprom’s application, as it was these same countries which provided Gazprom with recommendations on where exactly Nord Stream 2 should be put down. What is more, the existing gas pipeline has been operating for several years now and has caused absolutely no harm to the environment whatsoever. However, the new law allows the Danish authorities to review applications on the basis of the potential threat to national security. The pressure on Denmark – the only country to have yet to respond to Gazprom’s application for construction in its territorial waters – has grown. If the application is denied, Gazprom will simply remap the route, which will not change the timeframe or costs to any significant degree.

As the attempts of the United States to block construction of Nord Stream 2 by proxy have proven unsuccessful (construction work has already started in Germany), we can expect Washington to start to take shots at the Russian project directly. Congress has already granted the President the right to prohibit the financing of new gas pipeline projects between the Russian Federation and Europe, as well as the provision of construction services. However, the European partners have already allocated loans to Gazprom, and construction has already begun. So, we can argue about the status of the “new project.” The most vulnerable area is the actual laying of the pipeline. To this end, Gazprom is leasing pipelaying ships from the Swiss company Allseas, with the procedure itself to be carried out by three ships in 2018–2019.

It is still unclear whether or not Allseas will pull out of the contract in light of the U.S. ban. In any case, the American sanctions against Nord Stream 2 will be a blow not only to Russia, but (and perhaps more importantly) to Europe itself. After all, it is becoming increasingly obvious that the United States it attempting to block the flow of Russian gas in Ukraine, and then reduce it, which will harm European economies. The history of the first gas contracts between Europe and the USSR demonstrates that it is possible to overcome pressure from the United States. Let us hope that this happens more often than every 50 years.

(votes: 4, rating: 5) |

(4 votes) |

RIAC and DGAP Report