Counteracting the attempts of the Islamic State group to seize Iraq has become a test case for possible U.S.-Iranian cooperation. And this test case has, by and large, failed.

The idea of a ”major deal” struck between the United States and Iran has recently been losing support. This is partly due to the fact that U.S.-Iranian talks on the nuclear issue are very difficult to push forward. The Iranians want their own uranium enrichment capacity, as the Russia-Iran contract to supply fuel for the Bushehr nuclear power reactor expires in 2021. The U.S. is urging Tehran to sharply reduce the number of centrifuges capable of enriching fuel for research reactors, arguing instead that the treaty with Russia could be extended.

Furthermore, some American politicians and political analysts believe that the United States erred when it recognized Iran's right to a nuclear program – arguing that Iran simply does not need nuclear energy. According to the Carnegie Center, the Bushehr power plant is one of the world’s most expensive reactors. Although it provides just 2 percent of the country’s electricity needs, it cost Iran about $11 billion.

Having failed to chart progress on the nuclear issue by the end of July 2014, the parties agreed to extend talks for another four months until November 24. As an incentive, Iran has received another 2.8 billion dollars in sanctions relief, but American officials warn that the Islamic Republic will not get any more until negotiations have concluded.

Against this background, a number of U.S. experts and politicians suggest giving up the idea of stabilizing U.S.-Iranian relations – bringing them to collaboration rather than letting the hostility seen today continue. They argue that it does not serve the best interests of the United States and is unlikely to be a stabilizing influence on the broader situation in the Middle East. In fact, it would be more likely to result in the creation of anti-Iranian Sunni bloc, which American political scientist Walter Russel Mead argues could unite rich radical Saudi Arabia and nuclear Pakistan. Optimists counter that Iran is the most stable country in the region, and that Washington and Tehran share many common interests in the Middle East.

Meanwhile, now, while the negotiations are ongoing, the United States and Iran have the opportunity to assess the real prospects for cooperation on a particular issue in which both parties’ interests coincide (at least in part), namely – stabilizing the situation in Iraq.

The Caliphate Threat

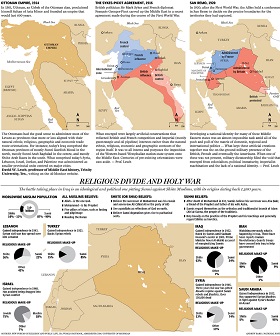

The invasion of Iraq by the Islamic State (previously known as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant or ISIS – and here referred to as the Islamic State or IS) and the seizure of large portions of Iraqi territory place in jeopardy not only the Iraqi state, but also the stability of the entire Middle East from the Tigris and Euphrates to the Mediterranean Sea. The Islamists want to create a vast Sunni extremist state, with the prospect of further expansion into Jordan, as well as resource-rich Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries. The ideological basis of this expansion appears to be the idea of a Caliphate, which, Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi says, unites Muslim lands within a religious state. According to Vali R. Nasr, dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, after the seizure of the Middle East these ambitions could encourage the state to “project influence across the Sunni world, from Africa to Southeast Asia”.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that ISIS not only has an ideology, but the money to implement such plans too. Thus, Islamists trade oil from the territories they have occupied, selling it on the black market at $30 per barrel. According to Iraq’s Oil Ministry, the exploitation of Iraq's oil fields alone brings ISIS up to a million dollars a day. Combined with oil recovery from the oil fields the group controls in Syria (most notably the Al-Omar oil field in Deir al-Zor in eastern Syria, seized from rival group the Nusra Front), the group’s total income could be nearing $100 million a month.

Gen. Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, noted that the Iraqi forces were not, on their own, capable of reversing the gains made by ISIS, despite the fact that United States spent an estimated $25 billion on training and equipping the Iraqi army prior to the U.S. forces’ withdrawal in 2011. Moreover, according to American intelligence sources, numerous Iraqi army units have either been infiltrated by Sunni insurgent informants or by members of Iran-backed Shiite militias. There was some hope that the Kurdish militia known as the Peshmerga, which took control of several cities, could hold back the militants in the north, but in early August 2014 the Islamists inflicted a series of defeats on the Kurds, forcing them to abandon their positions. The militants took control of a number of new infrastructure projects, including the country's largest dam near Mosul. Should the dam be destroyed, all Iraq’s major cities downstream would be flooded. Not surprisingly, the Shiite government headed by outgoing Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has repeatedly asked both Washington and Tehran for help.

Need to Save the Kurds

Although Washington is well aware of the threat posed by the Islamic State, the United States has long been reluctant to deploy troops to save Iraq. It wanted to take advantage of the situation and remove the unwanted regime of Nouri al-Maliki. The U.S. only changed its position in early August 2014, when its allies – the Kurds – found themselves under threat.

The United States maintains that Maliki’s removal would weaken support for the Islamists in the Sunni provinces. Sunni tribal militias and the Islamic State “stay together only to fight the enemy, and that is the Prime Minister”, argues Iraqi political analyst Najim al Kasab, who has contacts among the Sunni insurgent groups. “If Maliki is replaced, the Sunni armed groups will turn on ISIS”. Sunni leaders acknowledge that they are not so much acting in support of the militants, but more in opposition to the Prime Minister, who they feel has deprived Sunni politicians of government control. “"I believe that Maliki is responsible for ISIS coming to Iraq”, said Sunni Sheikh Hatem al-Suleiman, who heads the Dulaimi tribe. “When we get rid of the government, we will be in charge of the security in the regions, and then our objective will be to expel terrorism – the terrorism of the government and that of ISIS”.

In reality, the “sunnification” of the Iraqi government was conceived by the Americans to weaken Iran's influence in the country. The United States hoped that the devolution of certain powers to anti-Iranian Sunnis and/or Nouri al-Maliki’s resignation from power would entail problems for Tehran and distract Iran from other regions of the Middle East. From that angle, even if Baghdad were to fall to Sunni Islamists it would not pose any particular problem for Washington, since the ultimate goal of diverting Iran’s attention from Palestine and the Gulf countries would have been achieved.

However, while pushing southward, the Islamists turned around and launched an offensive on the Kurdish territories, and this meant the situation for the United States changed dramatically. As a result, Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, and key U.S. interests were threatened. It is no secret that the United States supports the idea of an independent Kurdistan. It wants to control Kurdish oil, and to enjoy the possibility of using the “Kurdish factor” to put pressure on Iran, Syria and even Turkey (there are large Kurdish communities in all of these countries, and the establishment of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan is sure to intensify their separatist sentiments). It is for this reason that President Barack Obama on August 7, 2014 decided to deliver missile and bomb strikes on Islamist positions, due to the threat to the lives of American citizens in Iraq (apart from diplomats there are about 800 American service members in the country) and massive human rights violations in IS-controlled areas (the Islamists have imposed strict sharia laws, and violations are punished by corporal punishment, amputation, and executions). Pentagon spokesman Rear Admiral John Kirby revealed that the first attack took place on August 8 against IS militants’ artillery positions used for shelling the Kurdish units defending Erbil.

The United States could even create a coalition (France has already expressed readiness to join the American air campaign, although ground operations are not currently an option). Notably, the U.S. House of Representatives on July 25, 2014 passed a resolution barring President Barack Obama from sending forces to Iraq in a “sustained combat role” without further congressional approval. Theoretically speaking, Barack Obama as President is free to send troops to participate in operations abroad for a short time. However, given the upcoming mid-term elections to Congress at the end of the year, Barack Obama does not want to antagonize the House of Representatives and does not need Republican accusations that he is set to send troops back to Iraq.

For Iraq against Kurdistan

Iran's interests in Iraq are somewhat different from those of America. Tehran is interested in maintaining a secular Iraq and considers the U.S. policy in Kurdistan almost as an existential threat, no less dangerous than the one that comes emanating the Islamic State.

On certain issues, the Iranians are ready to show understanding and make allowances for U.S. interests. In particular, this applies to Nouri al-Maliki’s resignation. Tehran realizes that Maliki is an antagonising factor for the Sunnis and Maliki’s resignation would not weaken the Iranian influence in Iraq. The years of work the Islamic Republic has put into the Shiite areas of Iraq, the Shiite militia’s loyalty to Tehran, comprehensive economic ties (the volume of bilateral trade between Iran and Iraq reached $12 billion in 2013 ) and the political tradition of appointing a Shiite Prime Minister (the President’s position in Iraq is reserved for the Kurds, while the one of the Speaker of Parliament – for the Sunnis) combine to guarantee that the Iraqi elite will refrain from appointing an anti-Iranian prime minister.

However, Iranians cannot support the U.S. policy aimed at maintaining Kurdistan’s independence (the President of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region Massoud Barzani has declared that he will hold a referendum on secession from Iraq within a few months). First, Iraqi Kurdistan is likely to become a point of attraction for the Iranian Kurds and thereby strengthen separatist sentiments among them. Second, Tehran does not want to see a new state emerge near its borders that strengthens the positions of its current regional adversary Israel, its future regional rival Turkey, and current global opponent the United States. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has rendered the Kurds moral support, stating that they deserve their own state. Ankara helps Kurdistan financially – the Kurdish authorities are allowed to export hydrocarbons via Turkey. It is no secret that the United States had close ties with the Kurds even before its invasion of Iraq. Therefore, it will spare no effort to prevent a referendum. According to some reports, Washington renders support to other influential Iraqi Kurd leaders, namely the head of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan Jalal Talabani, who favors a single, united Iraq.

As to eliminating a major threat to Iraq posed by IS, the Iranian army – unlike Washington – has provided substantial support to its eastern neighbor Special operations units of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as well as its head and living legend of the Iranian Armed Forces Brigadier General Qasem Soleimani have all arrived in Iraq. However, Iran's ability to help the Iraqis is restricted by U.S. obstacles to Iranian support. The United States believes that Iran's active participation in the fight against IS would allow Tehran to increase its influence in Baghdad, while also depriving the Iraqi authorities of the incentive to implement internal reforms and hand over some powers to the Sunnis. Not everybody shares this point of view, but it seems that it dominates in the White House.

Consequently, if the United States were to deny military assistance to the government of outgoing Nouri al-Maliki, Iran would face a difficult choice. The Islamic Republic can take the salvation of Iraq upon itself, but given the assistance it already offers to Syria, the Iranians risk facing a dramatic overstrain of their resources and also a possible conflict with the Americans. This could also provoke a conflict with two other regional powers that view Iraq as among their interests, namely Turkey and Saudi Arabia. However, should the ayatollahs adopt a passive position, and should the Islamic State give up the idea of taking Erbil and instead resume its march on Baghdad, the Iranians face the risk of not only seeing an unstable territory form on its western border, but also of ceding part of its influence on Syria and the broader Levant.

***

Therefore, as of today, U.S.-Iranian cooperation on Iraq seems to be a non-starter. The main reason for this failure is the continuing lack of trust between Tehran and Washington. Both countries blame each other (and not without reason) for trying to exploit the situation in Iraq to the detriment of the other side. And this is despite the fact that, strategically, (putting the U.S.-Iranian conflict aside) an Islamic State victory in Iraq poses a threat not only to Iran but to the United States too. If the Islamic State is victorious, radicalism is likely to spread across the U.S.-allied monarchies of the Gulf and Jordan. That is why, if Washington does not want to deploy troops to Iraq, it makes sense for it to take a “leap of faith” and let Iran handle the Iraq problem. In turn, the Iranians would probably appreciate Washington’s goodwill, and the negotiating process on the nuclear issue would become more effective. If it ends in success, the United States and Iran would be able to proceed to solving other common problems in the Middle East.