Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine's economic development has been neither consistent, nor steady. During the decade 1989-1999, Ukraine's GDP fell by almost 61%, but in the 2000s and up to the global financial and economic crisis, GDP growth in Ukraine averaged about 7.5% per year [1]. The country began to face serious economic problems in September 2008, resulting in a fall in GDP by 14.8% in 2009 [2]. The government resorted to emergency measures, drawing on 16.4 billion dollars from the IMF in 2008 and 15.1 billion dollars in 2010, but failed to launch structural reforms. The economic growth resumed in 2010 at about 5% a year, but in 2012 froze at 0.3% [3]. The situation in the country has become critical, and the beginning of military operations in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions coupled with Crimea’s reunification with Russia only exacerbated it.

Crimea and Donbass: The price paid

In purely economic terms, the impact of Crimea’s secession from Ukraine has been relatively insignificant, and is estimated at about 3.8% of total GDP [4]. The region was not known for having a high standard of living, as GDP per capita there was less than €5,000 in 2012 against the national average per capita GDP of €6,800, with the maximum reaching €20,700 in certain regions [5]. The share of total exports of goods from Ukraine to Crimea was 1.6% and about the same figure describes Crimea’s share in the country’s total imports in 2013 [6].

The Luhansk and Donetsk regions, also known as Donbass, are much more important for Ukraine’s economy. In 2012 the Donetsk region had the highest per capita GDP, €20,700, while the corresponding figure for Luhansk varied from €6,500 to €9,500 [7]. Donbass’ share in Ukraine's GDP was 16% in 2013; the Donetsk region, with its 103 large enterprises outranking other regions in contribution to GDP terms, while the Luhansk region had 28 large enterprises. Donbass accounted for 25.2% of Ukraine’s total exports and 7.7% of Ukraine’s total imports [8].

The signing and ratifying of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement on September 16, 2014 indicates that, in time, the trade flow’s geographical distribution is likely to change, and the EU’s role as Ukraine’s economic partner will increase. Under the provisions of this Agreement, in the next ten years it is planned to create a free trade area between the EU and Ukraine. However, on September 12, 2014 the trilateral ministerial meeting between Russia, Ukraine and the EU opted to postpone the implementation of the Agreement’s economic and trade package until December 31, 2015.

Russia has also confirmed that it will maintain a free trade regime between CIS countries and Ukraine, until all necessary consultations and negotiations are completed. The EU and Russia have approximately the same share in the Ukrainian exports, which in 2013 amounted to about 30% [9]. The share of goods exported to Russia in 2013 accounted for 8.3% of Ukraine’s GDP, whereas that to the EU – only 0.8% of GDP. While Russia is one of Ukraine’s major trading partners, in 2012 Ukraine’s share in Russia’s total imports amounted to 5.7%, compared to 8.1% in 2004 [10].

The Donetsk region ranked first in the regional structure of Ukrainian exports to Russia: in 2012 it accounted for 18% of it [11]. The Luhansk and Zaporozhye regions ranked third in this respect: at 10% of the country’s total merchandise exports. The share of Crimean goods in Ukraine’s total exports to Russia was minimal, amounting to about 1% [12]. Aside from Russia’s share in the country’s total exports, Russia’s share in the regions’ exports is also worth noting. In 2012, 43% of the Luhansk region’s exports went to Russia, 22% and 29% – of those of the the Donetsk region and Crimea, respectively [13]. Nearly 10% of all production in the Luhansk region was directed to Russia [14], well ahead of other regions . The respective figures for the Donetsk region and Crimea were 6% and 2% [15].

Probability of default

The simplest definition of default is a delayed payment of principal and interest. Regarding the state, one key macroeconomic indicator that suggests a default is the amount of public debt as a percentage of GDP. In 2013, Ukraine's state debt amounted to 41% of GDP.

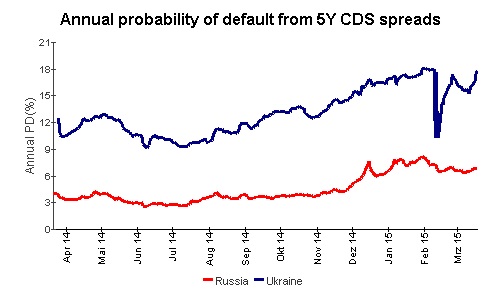

According to various estimates, in 2014 Ukraine’s national debt could exceed 60% of GDP. On the face of it, this data does not look disastrous, since the public debt of some European countries exceeds 100% of GDP. In 2015, Ukraine will have to pay 11 billion dollars to discharge its debts, including 3 billion dollars to Russia. The complexity of the situation in Ukraine is due not to the amount of debt, but to the almost complete lack of resources to service it. In December 2014, foreign exchange reserves decreased by 57% and amounted to just 7.5 billion dollars, compared with 17.8 billion dollars in January 2014. To protect part of the reserves, in November 2014 Ukraine’s Central Bank ceased currency interventions to maintain the exchange rate of the Hryvnia. As a result, the Hryvnia rate against the dollar had a triple fall from 7.9 Hryvnias for one dollar in 2013 to 24.5 Hryvnias in February 2015. As of mid-March 2015, experts at Deutsche Bank’s research division assessed the default probability in Ukraine at 17.8%, which is second only to Venezuela, whose risk of default is estimated at 19.6%. Given the worsened economic outlook for Russia and its sovereign rating downgrade by the leading rating agencies, the probability of a default in Russia is estimated at 6.8%.

For Russia, the threat of default emanates largely from the drop in oil prices and high refinancing rate, which hinders business. Ukraine, by contrast, requires an immediate infusion of funds to make payments to the private sector.

Reforms and/or money?

In an interview with Die Welt in early February 2015, Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko revealed that the military operation in Donbass is costing the country €7.5 million daily.

It should be added that in addition to the above, 25% of industrial enterprises have ceased production, infrastructure and housing in the conflict zone have been damaged, economic growth is non-existent and migration from Donbass amounted to nearly two million people, including about one million people registered as “internally displaced persons” in other parts of Ukraine and over 800 thousand people who have fled to Russia.

These circumstances cast doubt upon the possibility of stabilizing the economic situation in the country in the short and even medium term. The IMF loan of 17.5 billion dollars, approved on March 11, 2015 indicates the need for rapid economic reforms and austerity policy. IMF experts give rather optimistic forecasts, and believe that these funds will help Ukraine achieve economic growth of 2% as soon as 2016, despite the fact that real GDP is expected to contract by 5% in 2015.

Ukraine’s Finance Minister Natalia Yaresko hopes to restructure the country’s debt and wants bondholders to provide 15 billion dollars in debt relief over four years, but talks on the issue appear extremely difficult and very slow. The Ukrainian government has not confined itself to obtaining loans from the IMF. Loans have been granted by the World Bank, the EU, the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Taking out loans at such a speed also enhances the risk of the country’s default.

Any reforms that the government puts into practice or pushes through are unlikely to win support among the population. Domestic gas prices have nearly tripled, there are fewer hospitals open, and reforms to the pension system against the backdrop of the national currency’s depreciation and increased military spending, risk sparking social tension and a new wave of protests. Ukraine’s government says it is prioritizing the fight against corruption, reforming the energy sector (reforming Naftogaz Uraine in line with the provisions of the Third Energy Package of the EU) and state-owned enterprises, as well as broadening the tax base and effecting the transition to an electronic system of collecting VAT.

The National Anti-Corruption Bureau, the Anti-Corruption Agency, and the office of Business Ombudsman have already been established. Respected expert on the economy of post-Soviet countries Anders Aslund has suggested that the EU should adopt the Marshall Plan for post-war Europe and channel funds to Ukraine, including on a free-of-charge basis [16]. George Soros also suggested active funding of Ukraine by European countries [17]. Andrius Kubilius, former prime minister of Lithuania, proposed that the EU commits 3% of its budget for 2014-20 in grants to Ukraine. In July 2014, the Ukrainian government formed a working group on the Marshall Plan for Ukraine, chaired by former Deputy Prime Minister Vladimir Groisman.

In late April 2015, Kiev hosted a conference on opportunities and conditions for the provision of additional financial assistance to Ukraine, which was attended by representatives of 56 countries. Conference participants expressed their dissatisfaction with the extremely slow pace of reforms in the country and emphasized the need to reform the gas sector. Nevertheless, EU representatives promised to provide the next tranche of macro-financial assistance to Ukraine, which amounts to €1.8 billion in loans, grants and financial aid, in addition to another €70 million to complete the construction of a new shield over what remains of the Chernobyl reactor. The United States is also planning to provide 18 million dollars in humanitarian aid to Ukraine, as well as 2 billion dollars in long-term warranties.

On the one hand, the hostilities that are underway in some regions of the country and the disastrous economic situation create loopholes for all sorts of financial machinations. On the other hand, the military conflict offers an opportunity not only to push for loans, but to get funds in the form of donor assistance too. President Poroshenko’s negotiations with his Western allies on military-technical assistance show that the rapid resolution of the conflict is unlikely, the agreements reached in Minsk notwithstanding.

The involvement of EU and U.S. leaders in the fate of Ukraine, neighboring states’ concern for their safety and active lobbying for arms deliveries to Ukraine indicate that efforts will be taken to avoid the danger of the country’s default. In addition, it is worth noting that a default would have severe impacts on foreign creditors, as Ukraine's external debt in 2014 amounts to 135 billion dollars, equivalent to 70% of Ukraine’s GDP. The provision of financial assistance by international organizations and foreign states, even on a pro bono basis, may prove to be cheaper in the long run than the consequences of a default. European leaders will find it hard to arrive at consensus on this issue, given the difficult economic situation in a number of its member states (Greece, Spain, etc.) and these states’ repeated efforts to receive funding from the EU for economic recovery, not to mention the taxpayers who are likely to prefer the funds were directed elsewhere.

Internet sources:

Official Website of the IMF - www.imf.org

Official Website of the State Statistics Service of Ukraine - www.ukrstat.gov.ua

Official Website of Die Welt the journal - www.welt.de

Official website of the Deutsche Bank research division - www.dbresearch.com

Official site of the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies - www.wiiw.ac.at

1. Aslund A., Why is Ukraine so Poor? Op-ed in RBC Daily, Moscow, November 5, 2014.

2. World Economic Outlook: Legacies, Clouds, Uncertainties, International Monetary Fund, October 2014. P.188

3. Ibid.

4. How to Stabilise the Economy of Ukraine. Final Report. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2015. P.13

5. Ibid. P. 14

6. Movchan V., Giucci R., Ryzhenkov M., Ukranian Exports To Russia: Sector and Regional Exposure. Technical Note Series [TN/03/2014], Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting and German Advisory Group, Berlin/Kyiv, May 2014.

7. How to Stabilise the Economy of Ukraine. Final Report. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2015. P.14

8. Ibid.

9. Idid. P. 33.

10. Movchan V., Giucci R., Ryzhenkov M., Ukranian Exports To Russia: Sector and Regional Exposure. Technical Note Series [TN/03/2014], Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting and German Advisory Group, Berlin/Kyiv, May 2014.

11. Ibid. P. 7

12. Ibid. P. 7

13. Ibid. P. 7

14. Ibid. P. 7

15. Ibid. P. 7

16. Aslund A., An Economic Strategy to Save Ukraine, Policy Brief November 2014. Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2014. www.piie.com

17. Soros G., A New Policy to Rescue Ukraine, The New York Review of Books, 5 February 2015. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2015/feb/05/new-policy-rescue-ukraine/