US-EU Economic and Political Conflict in the Second Trump Era

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Deputy Director for Research at the Institute of Europe, Russian Academy of Sciences (IE RAS), Head of the Country Studies Department, Head of the Center for German Studies at the Institute of European Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

Late in 2024 – early 2025, new external and internal conditions for the economic-political postures of the United States and the European Union, as well as their constituent entities (50 states and 27 countries) were burgeoning. Last year, the main events took place in November (election of the new old president, collapse of the “traffic light” coalition in the Federal Republic of Germany) and December (the European Commission now made up of 27 Commissioners setting to work, early parliamentary elections ruled in Germany). However, it was January 2025 that proved most crucial, with Donald Trump returning to the White House and Brussels presenting the “Strategic Compass,” prepared based off Mario Draghi’s report. The designated period marked the beginning of a new cycle of strategic confrontation between the two key actors in the transatlantic space.

As the world enters the era of Donald Trump’s second presidency, it finds itself in a state of geoeconomic and institutional instability. The EU, which until recently tried to hold on to its role as global “regulator” and guardian of multilateralism, is increasingly operating not as a strategic actor, but as an arena where the interests of external players are clashing and exerting considerable pressure on the Union. This pressure comes above all from the U.S. and China, and is further exacerbated by the internal problems of the European “Standort”. In the current context, there are three possible scenarios for European Union and its development trajectories in the short and medium term.

Scenario 1: Transatlantic Mobilization

Assuming the continuation of external pressure, the EU, Germany and France—firstly—will finally decide to go forward with institutional consolidation. A possible trigger could be a new round of reciprocal protectionist measures (as a consequence of introducing retaliatory tariffs), threatening key EU exporters.

Scenario 2: Fragmented Europe

Partial fragmentation of the European space may be most realistic in 2025-2027. Major EU member states will prefer their own tactics in responding to external challenges. Germany and the Netherlands will maintain their export dependence on the U.S. and China but will somewhat minimize their participation in the EU’s collective actions. France will focus on strengthening elements of its strategic autonomy, while Italy and Eastern European nations will prefer to balance between Brussels and Washington. As a result, the EU will have chances to preserve its external instruments but will lose efficiency in institutional coordination.

Scenario 3: Strategic Triangular Structure

Brussels is staking on the further autonomization within the EU-U.S.-China triangle. In doing so, it will try to cast itself as an arbiter capable of playing up the divisions between the U.S. and China. It will be able to do this if it carries out reforms in the EU budgetary mechanism, mobilizes its industrial and defense potential, and strengthens digital sovereignty.

In any case, future transatlantic relations do not promise comfortable conditions for U.S. and EU economic and political actors. However, it does open up opportunities for Europe to rethink its role within the collective West in the global economy and politics. The current standoff within Euro-Atlantic relations is less about nation states and more about emerging economic macro-spaces and their competing economic models—for main production factors and for the global definition of norms, standards and development models.

Late in 2024 – early 2025, new external and internal conditions for the economic-political postures of the United States and the European Union, as well as their constituent entities (50 states and 27 countries) were burgeoning. Last year, the main events took place in November (election of the new old president, collapse of the “traffic light” coalition in the Federal Republic of Germany) and December (the European Commission now made up of 27 Commissioners setting to work, early parliamentary elections ruled in Germany). However, it was January 2025 that proved most crucial, with Donald Trump returning to the White House and Brussels presenting the “Strategic Compass,” prepared based off Mario Draghi’s report. The designated period marked the beginning of a new cycle of strategic confrontation between the two key actors in the transatlantic space.

New Euro-Atlantic Economic and Political Realities

Trump’s Tariff Hammer and the Strategic Calculus Behind the Mar-a-Lago Accord

November, December and January became new milestones and starting points for the era of transformation in US-EU economic and political relations. Washington’s key cabinet appointments confirmed Trump’s strategic focus on rethinking US economic priorities. The strengthening of the protectionist faction in Washington is quite indicative. One of the most influential architects of this new policy is current presidential adviser Peter Navarro, who openly criticizes globalism and advocates strict redistribution of global supply chains in favor of the U.S. manufacturing industry. Also notable is the legacy of Trump’s first term—the ideas of Larry Kudlow and other representatives of the “MAGA-intellectual elite,” who actively promoted “regaining of control” over trade flows and U.S. reindustrialization rooted in economic nationalism.

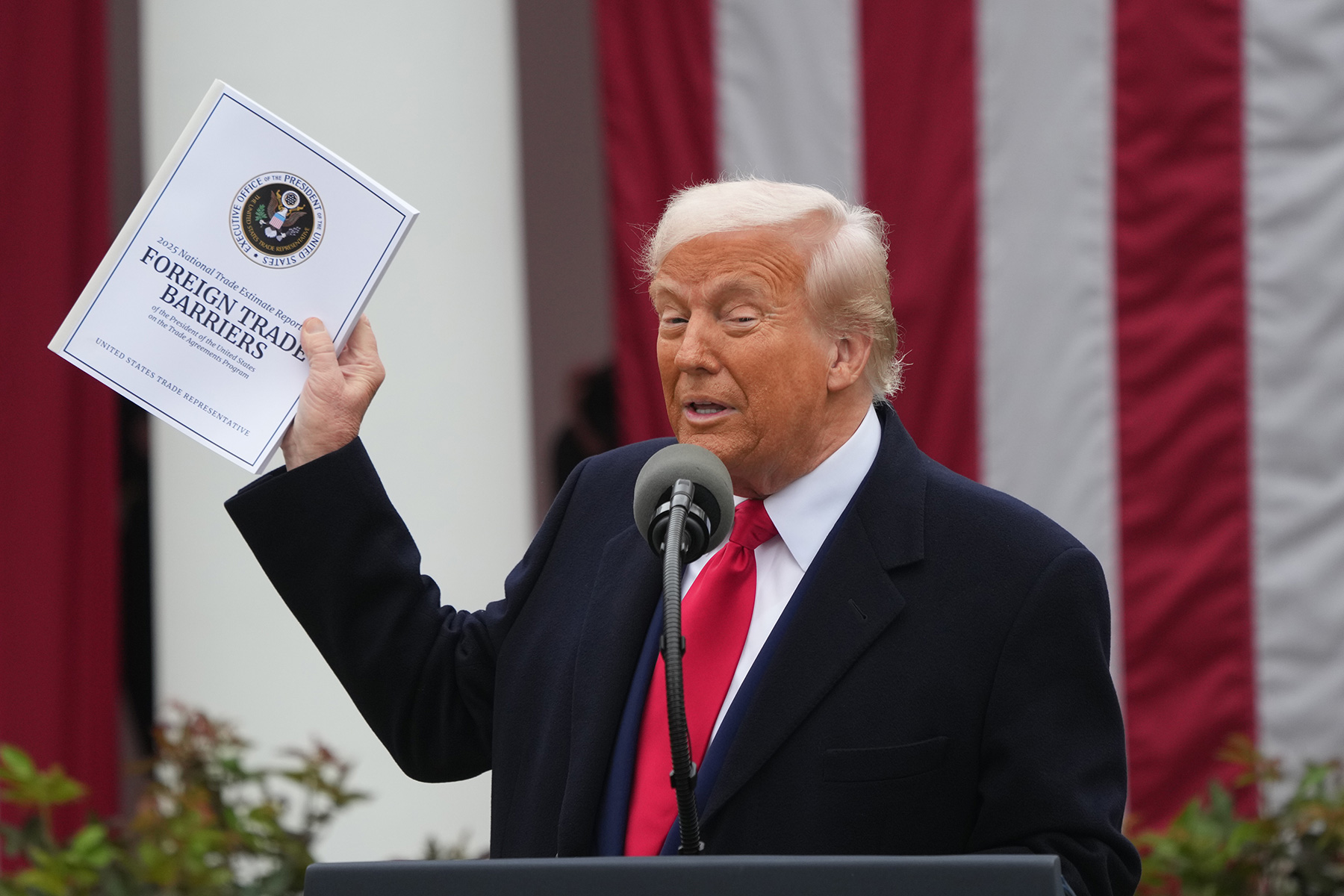

By the end of March, the White House prepared a “Reciprocal Tariffs” strategy—a tariff regime aimed at “restoring the balance in international trade” and protecting domestic producers. In parallel, Trump supported the “Make America Wealthy Again” (MAWA) initiative—an economic version of his “America First” foreign policy program, but with an emphasis on the flow of capital and manufacturing capacity from the EU and China back to the United States. These measures marked the beginning of a new phase in tariff confrontation, potentially undermining WTO principles. As expected, this approach caused justifiable alarm in Brussels and other European capitals. In the late evening of April 2, such anxiety proved well-funded, as Trump put out an official statement, launching the above-mentioned strategy. New tables presented mirror tariffs and for the EU, they were set at 20%.

After the July (2024) elections in the European Parliament (EP) and the formation of the executive branch, the EU also entered a new phase of the institutional cycle in the second half of 2024. The renewed composition of the European Commission (EC), chaired by Ursula von der Leyen and influenced by the centrist bloc of the EP, had to immediately respond to the challenges from Trump. Although the chairwoman and her colleagues had been preparing for them in advance, the search for adequate responses was significantly delayed. Among the main reasons is the political fragmentation in the EP, the presence of strong Eurosceptic factions and poor coordination between the key EU capitals. All of this has significantly hampered the shaping of the Euro-Atlantic consensus.

Thus, in the first quarter of 2025, the contours of a new reality in the Euro-Atlantic region took shape. They can be characterized as follows: a confrontational but not broken transatlantic economic landscape. Within its framework, EU institutions are trying to build a defensive position, while Washington demonstrates readiness for economic revisionism built on protectionism. The next stage of Euro-Atlantic relations will unfold in the realm of clashing economic interests and inevitable conflicts, where Germany plays the role of the European Union’s central hub.

Germany: The Epicenter of Clashing Market Economy Models

Amid the global reshaping of geoeconomic priorities, Germany finds itself at the center of a mounting collision between two economic and political approaches: U.S. neo-protectionism and the European model of “green” transformational development.

In 2023-2024, the German industrial sector continued to show a steady decline, especially in key industries (automotive and mechanical engineering, chemicals, etc.) The reasons include rising energy and electricity costs, falling external demand, and an uncertain investment environment. The “green” transition strategy, formally supported by the previous German governments, in practice turned out to be uncompetitive amid the global redistribution of production chains [1].

In this context, Washington’s actions—including the introduction of “Reciprocal Tariffs” and the continued implementation of the “Inflation Reduction Act”—keep Germany at risk of further loss of its economic stronghold’s competitiveness. German companies, especially in the automotive and engineering sectors, have already been faced with the choice of adapting their economic locations to the attractive jurisdiction of the U.S. or abandoning it, hence losing access to key incentives and subsidies. Starting in 2022, the leading German concerns (BMW, BASF, Siemens, etc.) are revising investment priorities, consistently strengthening U.S. (as a top-priority) and Asian (primarily Chinese) directions.

Around the same time, the German authorities have been trying to develop a unified strategic response regarding their main foreign economic partner. During the 20th Legislature, Chancellor Olaf Scholz used cautious rhetoric towards the U.S., preferring “quiet diplomacy” and “balanced relations” with the former president. However, Robert Habeck—Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection—actively criticized Washington’s actions, pointing to the risk of German deindustrialization. Former Finance Minister Christian Lindner opposed large-scale subsidies as part of Germany’s business support measures, citing the need for budget discipline.

Leading German industry trade associations (BDI, DIHK, BDA, etc.) during 2023–2024 were consistently dialed up pressure on the “traffic light” coalition to expand support for the real sector [2]. In their expert materials, they mentioned the “double pressure” on their members—both from the U.S. subsidies and state support for Chinese business “expansionism.” However, a constructive dialogue between businesses and government failed, which was one of the reasons for the coalition’s collapse in early November 2024.

Thus, the economic leader (albeit a “sick” one) of the European Union in the Euro-Atlantic context found itself in a very vulnerable position. In fact, the German “Standort” was actually turning into a battleground for conflicting transatlantic economic models—U.S. and European—where every measure taken by the U.S. or the EU is fraught with instant consequences for the activities of its economic entities. There is a clear paradox: German statesmen, who for many years have stood up for trade liberalization and global cooperation, are now forced to balance between preserving the principles of “ordoliberalism” and the need to adapt to current geopolitical challenges.

Such adaptation is not so much a problem of the future as of the present. It is being discussed as part of the ongoing coalition negotiations between the CDU/CSU and the SPD. The question, however, for the members of the future Cabinet is no longer whether to react or not, but which way to go and with whom. In this regard, the decision of the former Bundestag to adopt amendments to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany, related to the reform of the “debt brake” and the creation of two special funds—for infrastructure (500 billion euros) and defense (400 billion euros)—for 10 years, has become a crucial issue for the future government. This means a significant expansion of opportunities for various government programs, where each of the above-mentioned parties is trying to “grab the biggest piece of the pie.” Naturally, this sparks conflict and heightens tensions. However, the nature of the current coalition negotiations seems to point more towards a likely compromise. The new policy will most likely combine an emphasis on the modernization of the “Standort” and on a response to external challenges, including the transformation of global value chains caused by Trump’s April initiatives.

The European Union: Adaptation Strategies and Internal Chasms

Can U.S. New Tariffs Trigger Structural Changes in Global Economy?

The European Union’s search for answers to the U.S. industrial revitalization and protectionism strategy has been complex and contradictory. The EU entered the year 2025 by introducing the Competitiveness Compass program, which included the main proposals of the September (2024) report by Draghi [3]. The strategic document contains general provisions on the consolidation of the industrial base, accelerating digital transformation, expanding the use of renewable energy sources, and reducing EU dependence on third countries in key sectors. These are mostly good intentions, the effect of which is still limited.

Industrial modernization, including the support for “green” and digital industries, is actively advocated by France, Italy, Spain and Portugal, all whom cite the vulnerability of their industrial structures. Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and the Nordic nations show more restraint, insisting on compliance with the Maastricht criteria and limiting new debt.

Emmanuel Macron views France as a guarantor of the EU’s economic sovereignty, vigorously supporting the idea of the Buy European Act and insisting on creating mechanisms similar to the U.S. IRA (e.g. giving priority to European companies in tenders and the distribution of subsidies). Nevertheless, there is a potential for conflict within the German-French tandem. For example, Berlin fears for the duplication of EU activities and shifting the center of gravity in support plans towards southern countries.

Poland, whose executive branch has been undergoing a transitional phase in recent months, demonstrates its readiness to support European solidarity, demanding at the same time the development of some compensation mechanisms for Eastern European members of the EU to promote their industrial sectors. The Baltic states and the Czech Republic emphasize security and increased defense spending over economic support.

The EU is building tariff and anti-subsidy policies to protect its own sensitive economic sectors (e.g., electric vehicles and solar panels). In 2024, the European Commission conducted several investigations and strengthened export controls on dual-use technologies. However, given the internal fragmentation of the European political space, these steps have not always enjoyed the unanimous support of EU member countries.

Here, arises a paradoxical situation: while striving to compete with the U.S. and China within the “geo-economic triangle,” the EU continues to show signs of institutional overload and political inertia. Decisions taken at the level of the European Commission face slow implementation and opposition within the EU Council. The divergence of national interests (e.g. between France and Germany) hinders the implementation of already agreed-upon measures.

As for the reaction of Brussels and key EU capitals to the U.S. decision to impose mirror tariffs, it was reserved and cautious, but principled. Ursula von der Leyen, while attending the international forum in Samarkand, stated “the need to preserve the rules of global trade,” emphasizing that the EU “will not give in to economic blackmail,” but is open to dialogue. Scholz said that “unilateral steps taken by the United States undermine trust and pose a threat to the global economy.” Macron called for “an immediate discussion in the G7 format,” while Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni noted, “the response should be united, but not emotional.” The leaders emphasized that the U.S. measures cast doubt on the future of the transatlantic economic partnership.

Thus, the EU has entered 2025 under forced economic and political mobilization, wherein the struggle for global competitiveness is coupled with internal budgetary, as well as institutional and political discrepancies. Whether the EU will be able to leverage its programs for boosting real growth is an open question, especially amid growing pressure from the U.S. and China.

The United States: The Return of a Protectionist National Doctrine

With Donald Trump’s accession to power in January 2025, the economic policy of the United States finally took shape as a rigidly protectionist paradigm, its cornerstone being the aforementioned “Reciprocal Tariffs” initiative, officially presented by the new administration as a key tool for “restoring fairness” in international trade. All in all, nations imposing higher duties on U.S. products than the U.S. does on their goods automatically receive “mirror tariff barriers.” This subjective logic of Trump and his advisers (it would be a mistake to look for sound economic reasoning) replaces the principles and rules of the WTO with bilateral and multilateral pressure being placed on partners, primarily EU member states and China.

The return of Peter Navarro and Kevin Hassett to the inner circle of the President’s economic advisers was accompanied by harder rhetoric against the EU, hinting at hidden protectionism, administrative barriers and discrimination against U.S. companies. In the meantime, threats were made to impose 25 percent tariffs on imports of automobiles, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.

Parallelly promoted is the “Make America Wealthy Again” (MAWA) doctrine—the economic basis of Trump’s second presidential term. This doctrine is focused on U.S. reindustrialization, the return of manufacturing capacity from abroad, strengthening domestic demand and autonomy in key sectors. The total amount of incentivizing measures is estimated at USD 1.5 trillion by 2030. Key areas include the battery industry, microelectronics, aircraft, shipbuilding and green technology.

The “Made in USA” label is once again proclaimed as one of the priorities for the current Trump economic strategy. Foreign direct investments, including those from the EU, are formally welcomed, but are subject to strict conditions. First of all, this relates to the localization of the entire production cycle inside the U.S. and compliance with technology transfer requirements. In this regard, Congress has expanded measures to support domestic production, including tax incentives, priority access to federal infrastructure tenders, as well as preferential lending for companies working in strategic sectors—energy, microelectronics, shipbuilding, aviation and “green technologies.”

In February 2025, as part of reinforcing investment sovereignty, the Interagency Committee for the Review of Investment Agreements was formed to update the conditions for the access of foreign investors to the U.S. market. In particular, the issue of excluding provisions from the agreements that allow arbitration claims against the U.S. by foreign companies within the framework of the ISDS (Investor-State Dispute Settlement) mechanism came to the fore.

Since the beginning of 2025, the White House has consistently increased pressure on US allies, including the European Union. Trump has clearly designated his position—“we no longer need partners who make money on us by creating a surplus in their home jurisdictions and deindustrialization in our country.”

The economic and political agenda of the U.S. administration is accompanied by attempts to completely revise the structure of international trade. The U.S. has de facto abandoned its participation in WTO dispute settlement mechanisms and is developing parallel trade and investment alliances, mainly with individual countries of the Global South such as India, Brazil, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia and Mexico. Washington is trying to become an architect of a global economic structure favorable only to the U.S., rather than simply being a guarantor. In this model, the European part of the “collective” West turns out to be a competitor rather than a partner, which is required either to adapt to “U.S. rules” or withdraw from the economic zones under U.S influence. It is obvious that the U.S. has put at stake not only its global trade superiority, but also the right to set the rules of future globalization.

Europe’s Response: Between Strategic Instinct and Institutional Hesitance

The European Union’s response to the return of U.S. protectionism has so far been fragmented. Although EU leaders have repeatedly stated the need for a common economic and industrial policy, national interests continue to dominate in practice, causing disagreements over major issues. This fully applies to the discussion of possible responses to the US initiatives (tariffs, MAWA).

At the institutional level, the current European Commission continues to create strategic autonomy mechanisms, including the introduction of analogues to the U.S. priority procurement system, the formation of a sovereign investment fund, the expansion of trade protection instruments, in addition to the intensification of anti-subsidy policies towards China and the U.S. However, moving forward remains difficult, also due to the lack of consensus among the “European comrades.”

Emmanuel Macron has taken the most proactive stance in this regard, calling for the formation of full-fledged economic sovereignty and fiscal reforms to finance a new industrial policy. France sees the current transatlantic challenge as a “window of opportunity” for reformatting the EU model itself “in the French way.”

Germany holds to a more cautious approach. While German industry representatives (especially in the automotive sector) are expressing alarm over U.S. tariffs, the technocratic government of Olaf Scholz continues to diplomatically cite the need to avoid a trade war. Robert Habeck emphasizes the importance of preserving the multilateral trading system and the role of the WTO (although Brussels itself is increasingly trying to circumvent this structure).

Italy and Spain support the French initiative but demand a fair distribution of resources and flexibility in the application of fiscal rules. Eastern European nations, especially Poland and the Czech Republic, are concerned that industrial programs may lead to the centralization of resources in the hands of the old EU member states, with the national protectionism of Paris and Berlin curbing the competitive chances and advantages of Poland and Czech Republic.

There is no unified position in the European Parliament, where some deputies demand an immediate and tough response to the United States, including the introduction of mirror tariffs and sanctions against U.S. subsidies. However, EP resolutions are non-binding and more often serve as a signal to organize public pressure rather than the desire to develop any specific strategy.

As of early April, the “European comprehensive response” to the “second Trump” is still only being formulated. So far, only partial outlines of the strategy can be discerned as tools are being developed. However, the political will of Brussels to implement them bumps against institutional barriers and differences in the economic models of EU member states. In this regard, the pressure from business associations and industry unions is growing, as they demand from Brussels not just empty declarations, but concrete protective measures and investments.

Clearly, the EU is once again at a crossroads between the desire for strategic autonomy and the fear of splitting the unity among its member states. The outcome will largely depend on the ability of key capitals, primarily Paris and Berlin, to find middle-ground solutions, as well as on the position of the new European Commission. In this respect, maintaining a skeptical viewpoint would be quite appropriate.

China as a Third Power: Strategic Balance and Asymmetric Response

Amid the economic confrontation between the U.S. and the EU, China is increasingly emerging as a “third power,” seeking not participation in conflict escalation, but rather to use the situation to promote its own interests. With Washington returning to open protectionism policies and Brussels oscillating between autonomy and transatlantic loyalty, Beijing is increasing its strategic flexibility and pursuing an asymmetric policy of simultaneous pressure and “temptation/seduction.”

China’s foreign policy rhetoric in 2024–2025 emphasizes the need for multilateralism, WTO reform, and the inadmissibility of “new bloc logic.” However, behind the declarations are pragmatic steps: the intensification of bilateral ties with European nations, especially Germany and France, the development of logistics infrastructure on the Eurasian continent within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as new investment formats with Southern European and Eastern European countries.

It is indicative that in March 2024, Beijing hosted Bavarian Prime Minister and Chairman of the CSU Markus Söder, in April—Chancellor Olaf Scholz, in June—Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck and Minister of Digitalization and Transport Volker Wissing, and in October—a Bavarian business delegation led by Deputy Prime Minister Hubert Aiwanger. The visits were accompanied by the signing of documents on cooperation in the fields of green energy, automobile manufacturing and university exchanges. This is an example of how China offers Europe an alternative cooperative model; one without ideological requirements, but with overall high economic efficiency [4].

Beijing is also actively responding to U.S. attempts to restrict Chinese trade and investment. The response includes increasing its own subsidy pressure, developing export control mechanisms, restrictions on rare earth materials, and strengthening domestic programs on technological autonomy. China is thus demonstrating that it is capable not only of adapting to the new configuration, but also of influencing the formation of its parameters.

Chinese diplomacy pays special attention to strengthening ties with the Global South, promoting Beijing’s image as the antipode of Western dominance. This allows China to position itself not just as a participant in the EU-U.S. conflict, but also as a “global arbiter” and leader of an alternative development path.

Despite Brussels’ attempts to tighten anti-subsidy controls, the “Middle Kingdom” continued making direct investments into Europe throughout 2024. By investing their capital in the European economy, China demonstrated its willingness to partner with local businesses. However, European company interests on cooperation with China do not always align with the policies of the European Commission.

China does not seek to “add fuel to the fire” of the transatlantic conflict. Its strategy comes down to constructively building its interests into the “fissures in relations” between the U.S. and the EU. It seems that Beijing, like Washington, is betting on a “divided Europe” and its individual pragmatic partners, especially in the “old” industrialized countries of the EU, while seeking a positive image of a global moderator.

In this context, Beijing’s approach can be described as “another Chinese warning”: one step back—three steps forward, one concession—four new conditions; verbally—for cooperation, practically—for the reassembly of the global economic order. The “Celestial Empire” has had enough room for maneuver, especially in the midst of Brussels’ current indecisiveness and Washington’s aggressive unilateralism.

Possible Scenarios and Strategic Implications: EU Between Hammer and Anvil

As the world enters the era of Donald Trump’s second presidency, it finds itself in a state of geoeconomic and institutional instability. The EU, which until recently tried to hold on to its role as global “regulator” and guardian of multilateralism, is increasingly operating not as a strategic actor, but as an arena where the interests of external players are clashing and exerting considerable pressure on the Union. This pressure comes above all from the U.S. and China, and is further exacerbated by the internal problems of the European “Standort”. In the current context, there are three possible scenarios for European Union and its development trajectories in the short and medium term.

Scenario 1: Transatlantic Mobilization

Assuming the continuation of external pressure, the EU, Germany and France—firstly—will finally decide to go forward with institutional consolidation. A possible trigger could be a new round of reciprocal protectionist measures (as a consequence of introducing retaliatory tariffs), threatening key EU exporters. In this case, the idea of creating a European Sovereignty Fund to support industrial projects and to enlarge the powers of the European Commission in the field of industrial and trade policy is likely to be brought back to life. However, this requires constructive initiatives on the part of the European Commission and the support of the political establishment from at least six to seven major EU economies, including Italy, Poland and Spain. The main risk will be the possible intensification of centrifugal processes within the EU and deterioration of its relations with the U.S.

Scenario 2: Fragmented Europe

Partial fragmentation of the European space may be most realistic in 2025-2027. Major EU member states will prefer their own tactics in responding to external challenges. Germany and the Netherlands will maintain their export dependence on the U.S. and China but will somewhat minimize their participation in the EU’s collective actions. France will focus on strengthening elements of its strategic autonomy, while Italy and Eastern European nations will prefer to balance between Brussels and Washington. As a result, the EU will have chances to preserve its external instruments but will lose efficiency in institutional coordination. Company investment strategies may become more nationally-oriented, creating in Europe a “mosaic” of its economic policies.

Scenario 3: Strategic Triangular Structure

Brussels is staking on the further autonomization within the EU-U.S.-China triangle. In doing so, it will try to cast itself as an arbiter capable of playing up the divisions between the U.S. and China. It will be able to do this if it carries out reforms in the EU budgetary mechanism, mobilizes its industrial and defense potential, and strengthens digital sovereignty. Such a scenario is not excluded if the political cycle changes in key EU countries, primarily in Germany and France, with a new generation of pro-European pragmatists emerging. Such a scenario may be the most acceptable in the long term and a strategically verified path for the EU leadership and its member states. The main challenge is to achieve a high level of political will and consensus to fill it with specific content.

With an eye on the strategic geopolitical consequences defined by Trump’s second term, the following points can be emphasized:

- No longer is there an unwavering loyalty between the EU and the U.S. Transatlantic relations are entering a phase of pragmatization and division of technological competencies of its participants

- China will be strengthening its role as a global stabilizer/moderator, exploiting EU indecision and U.S. political radicalism

- The EU faces the need to reassess its industrial model, trade policy and digital sovereignty principles or risk becoming an economic appendage of competing global stalwarts

- Germany, as a backbone of the EU, is in a unique position. Either it can lead in restarting the European economic structure or become drawn into the U.S.-China competition with limited choice on the terms.

In any case, future transatlantic relations do not promise comfortable conditions for U.S. and EU economic and political actors. However, it does open up opportunities for Europe to rethink its role within the collective West in the global economy and politics. The current standoff within Euro-Atlantic relations is less about nation states and more about emerging economic macro-spaces and their competing economic models—for main production factors and for the global definition of norms, standards and development models.

1. Belov V.B., Kotov A.V. The Green Transition of Germany under the German “Standort” Transformation // The Problems of National Strategy. 2025. № 1 (88). p. 180–199. DOI: 10.52311/2079-3359_2025_1_180

2. Belov V.B. “Standort” Dialogue between Government and Business under Multiple Crises in Germany // Scientific and Analytical Bulletin of IE RAS. 2024. № 5. p. 37–50. DOI: 10.15211/vestnikieran520243750

3. Belov V.B. Challenges for Competitiveness of the German Economic and Political Space. Modern Europe, 2024, № 6, p. 79-88. DOI: 10.31857/S020170832406007X

4. Belov V.B. Germany's Relations with China: the Uneasy Trinity of Partnership, Competition and Rivalry // Relevant Problems of Europe, 2024. № 4. p. 199-222. DOI: 10.31249/ape/2024.04.11

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

There is a combination of factors that may contribute to easing the most confrontational aspects in Russian–German relations

China’s De-dollarization Mechanisms within the Yuan Internationalization StrategyRIAC Report #98

Can U.S. New Tariffs Trigger Structural Changes in Global Economy?What kind of order is it, if it is so easy to disrupt?

Trump’s Tariff Hammer and the Strategic Calculus Behind the Mar-a-Lago AccordTrump’s tariff hammer and the Mar-a-Lago Accord form a strategic triad—protectionism, fiscal relief, and geopolitical leverage—to reboot U.S. hegemony