Nord Stream 2 is the most dynamically developing gas transportation project in Europe. Even though the stakeholders only signed the Agreement in September 2015, 10 months later the outlines of Nord Stream 2 are already clear and precise. Still, Nord Stream 2 has to deal with several issues, which will pose a serious challenge for the international consortium.

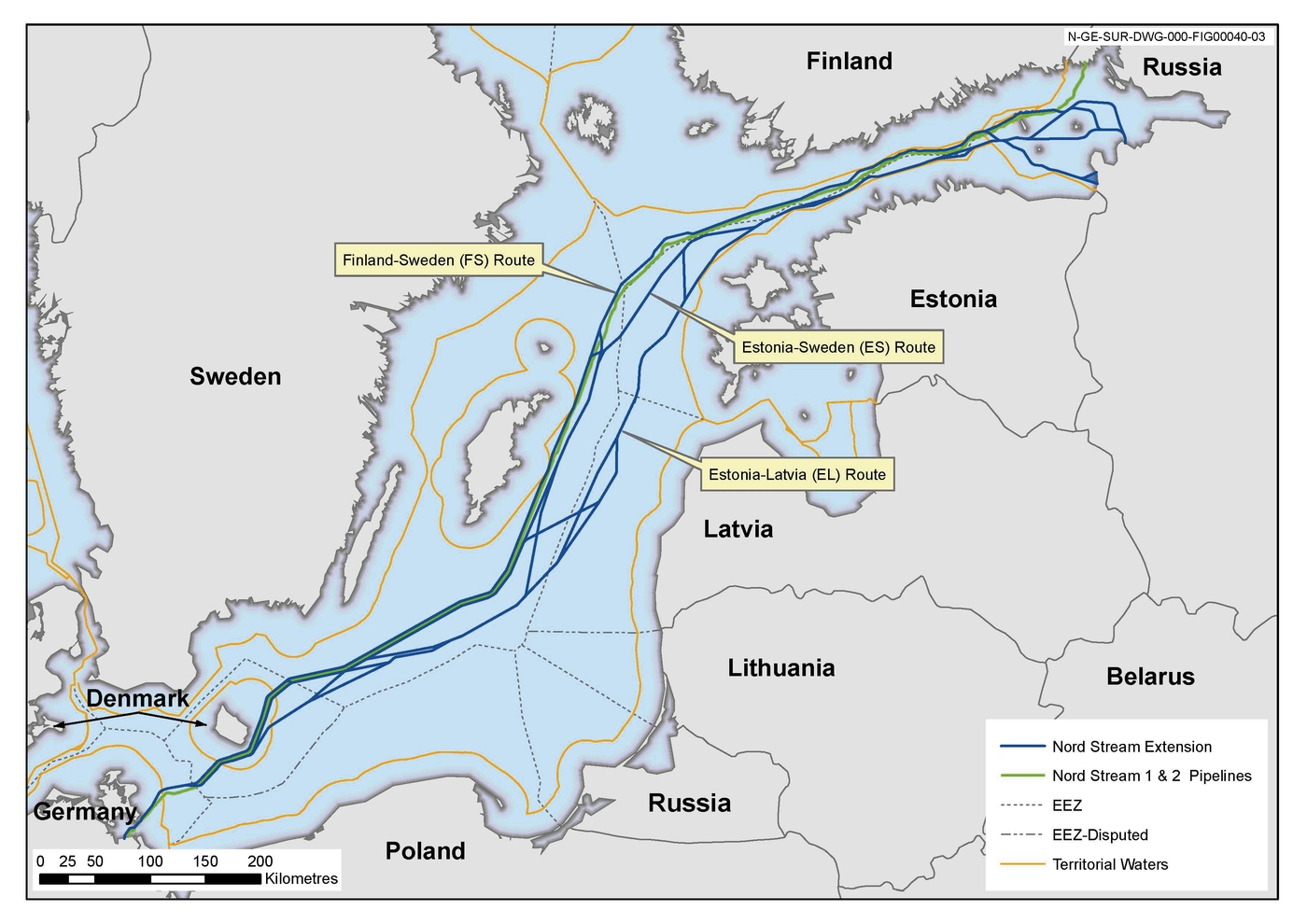

Nord Stream 2 is the most dynamically developing gas transportation project in Europe. Even though the stakeholders only signed the Agreement in September 2015, 10 months later the outlines of Nord Stream 2 are already clear and precise. The stakeholders intend to build and put into operation two new lines with a capacity of 55 billion cubic metres under the Baltic Sea by 2019: this is when the contract between Gazprom and Naftogaz for the transit of natural gas through Ukraine expires. With the support of several leading European energy firms including Royal Dutch Shell, E.On and Engie, Gazprom is steadily moving forward through the project’s first stages. A tender was held recently for the production of pipes for the pipeline, which was was won by the Dutch company Wasco Coatings Europe BV.

Still, Nord Stream 2 has to deal with several issues, which will pose a serious challenge for the international consortium. In late July 2016, Poland’s national energy regulator (UOKiK) put forward objections to the construction of Nord Stream 2. Poland does not want reduced competition in its gas market. This reaction was to be expected, since the Polish authorities had previously stated they would only greenlight the project if it were to pass through Poland. Apparently, laying a pipeline along the bottom of the Baltic Sea, even in Poland’s territorial waters, will not bring in the amount of transit payments that Central European states are used to receive. Obstruction on the part of Poland will, apparently, lead to the country rejecting the project outright. It will then be considered by the European Commission.

Germany, the European Union’s economic leader, may largely decide the future of Nord Stream 2. Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel has already said that Nord Stream 2 will be implemented regardless of the sanctions against Russia and that it is on the Germany’s economic projects list. Germany could also influence those states whose energy regulators have not yet made up their minds with regard to laying Nord Stream 2 in their territorial waters, such as Finland, Sweden and Denmark. Gazprom’s partners in the project, Royal Dutch Shell, E.On, OMV, Wintershall and Engie, also have significant lobbying powers. The European Commission insists that Nord Stream 2 cannot exist “in a legal void, or according to Russian law only.”

Speaking at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, Jean-Claude Juncker notably said that Europe has a “strong preference for pipelines that unite rather than for pipelines that divide.” Two weeks later, Gazprom succeeded in reaching an agreement with Slovakia’s Eustream on using Slovakia’s gas transport system as part of Nord Stream 2. Gazprom’s negotiating position was also favourably affected by the failed military coup in Turkey, which led to a rapprochement between Moscow and Ankara and a renewal of Turkish Stream negotiations. Relations between Turkey and the European Union have cooled noticeably after the attempted military coup, partially because of Recep Ergodan’s threats to introduce death penalty, which could complicate their cooperation on the Southern Gas Corridor.

Gazprom’s rhetoric concerning a move away from Ukrainian transit and toward the Baltic route has become more sophisticated. As Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller said, due to gas production gradually shifting away from the basins of the Nadym, Pur and Taz rivers to the north – toward the Yamal Peninsula – it is not expedient from an economic point of view for Gazprom to adhere to the longer transit route via Ukraine. It should be noted that after the main source of the gas that is to be transported via Nord Stream 2 (the Bovanenkovo gas field in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Region) reaches its top production capacity in 2023 (115 billion cubic metres), it could fill both new lines of the pipeline. As Gazprom officials have claimed, Nord Stream 2 transit payments for transporting 1,000 cubic meters 100 kilometres are twice as profitable as the tariff set by Ukraine’s National Commission for State Regulation of Energy and Public Utilities ($2.10 vs. $4.50).

A strong argument in support of Gazprom’s position is the condition of the Ukrainian gas transport system (GTS), which is in need of a major overhaul. It is not profitable for Gazprom to undertake financial obligations to modernize an old GTS, since no one can guarantee political stability in Ukraine, and since the Ukrainian authorities are traditionally hostile toward Gazprom. In 2011, Ukraine’s Naftogaz estimated the cost of modernizing the GTS at $3.5 billion, and since then the cost has only grown, because energy has been put on the backburner of Ukrainian politics over the last three years, and no modernization programmes have been initiated. Thus, Gazprom intends to gradually minimize the use of the Central gas transportation corridor (i.e. the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhgorod pipeline) and stop using 4,300 kilometres of gas pipeline and 62 compressor stations by 2020. After 2020, Gazprom plans to have transit capacities on that route of about 10–15 billion cubic metres.

The interest of western European states and, in particular, leading industrial groups, is due, among other things, to the general measures of environmental protection. In accordance with agreements achieved at the UN Climate Change Conference in December 2015, gas could become “transitional fuel” for European countries which, apparently, will face significant difficulties in carrying out the obligations they undertook to create sustainable energy sources. For instance, France has set the target of increasing the share of renewable energy in final energy consumption to 32 per cent. However, the country’s hydropower capacities have been stagnating for years (11 per cent), while the second most important renewable energy source, wind energy, takes up only 3.8 per cent in the country’s energy balance. Despite the impressive growth of wind energy use in Germany, coal still dominates the country’s energy sources. In Holland, coal consumption grew by 19 per cent in 2010–2015, and gas imported from Russia could be a way to cover the Dutch fields dropping production without the risk of paying taxes on CO2 emissions.

Out of Gazprom’s three latest gas transportation initiatives (the South Stream, the Turkish Stream and Nord Stream 2), Nord Stream 2 has the greatest chance of being implemented. By the end of 2016, it will be clear whether Nord Stream 2 will have to deal with regulatory pressure from the European Commission, or whether Brussels will greenlight the construction of the new lines, making the Baltic supply route the dominant route in the European Union.