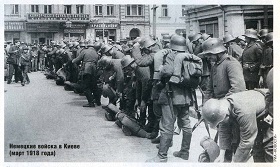

When Did the First World War End for Russia? Marking the Centenary of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Brest-Litovsk, March, 1918

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Member of the Russian Association of First World War Historians, Master of Political Science (MGIMO)

For many Russian citizens, March 3, 1918 did not mark the end of the First World War. Moreover, the concept of the “lost victory”, according to which Russia’s generally successful course of action during the First World War was artificially cut short by the revolutionary upheavals of 1917 and the country was deprived of victory by various revolutionaries, had already begun to take hold among military émigrés.

According to the official Soviet historical narrative, the First World War was a war that never ended. It did not have its own “identity”, becoming a catalyst for objective socio-economic conflicts and the “zero point” of the 1917 revolution. All the events after February 1917 were regarded not as part of the First World War itself, but as part of the Revolution and the Civil War. As if by a wave of the hand, the First World War (which itself was portrayed as a series of defeats and failures) was left behind in the old autocratic world; it was squeezed out of the history of the new world, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was nothing more than one of the stages which the Bolsheviks had to pass through on the road to the socialist future.

When did Russia get out of the First World War? The official answer is simple: on March 3, 1918, when it signed a separate peace treaty in Brest-Litovsk, which was occupied by the Germans. It was signed on one side by the Bolshevik government and on the other by the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire). The key points were the loss of about 780,000 sq km, including part of Transcaucasia, the Baltic region, and Ukraine, and also the effective recognition that all the military efforts of the past three and a half years had been in vain. In the supplementary protocol of August 27, 1918, Soviet Russia agreed to pay a war indemnity of 6 billion marks (officially for the upkeep of prisoners of war). The Germans ended up in possession of major Ukrainian reserves of iron ore and manganese, which were very important to Germany in the context of the continuing war of attrition.

But what was the peace of Brest-Litovsk, and did it mark the conclusion of Russia’s involvement in this war? This is where we encounter two key historical narratives based primarily on differing attitudes to the events of the First World War, the 1917 Revolution, and the subsequent Civil War. It is not so much a matter of academic discourse as of historical memory, constructed on the values and emotions sparked by different attitudes toward historical events.

One tradition is linked to the question of how these events were interpreted within the official Soviet historical narrative, in which the key role was played by the Great October Socialist Revolution (the founding myth of the Soviet state), and all the other events were set out in relation to it in a single teleological perspective. Everything “before” was the road to revolution, and everything “after” was accomplishment and successful progress. In this context, the Brest Peace was both the conclusion of a world war that the people did not need and a necessary tactical move in the face of German military pressure.

Some historical context

Here we need to clarify a number of historical events. In 1917 the Bolsheviks came to power largely thanks to anti-war rhetoric, and their first decree was the Decree on Peace. After several years of war, all the warring countries had seen a rise in anti-war feelings, but it was Russia where their growth was strongest. The main causes were that spare parts were in short supply, people were tired of trench warfare, the front was far away from the soldiers’ homes, the war aims were irrelevant to the majority of the lower ranks (weak national self-consciousness), the economic situation in the rear was worsening, and people were disappointed with the results of the 1916 campaign.

What we need to consider first is the widening sense of injustice that was eroding the fabric of society. The soldiers in the trenches considered it unjust that they were spending weeks under fire while others were sitting it out in the rear. The troops who had been mobilised complained about those who had contrived, through bribes or connections, to secure a warm billet at headquarters well behind the lines. Others believed it was unjust that the generals were gambling with their lives for nothing, since they were incapable of bringing their troops to a swift victory. “Why should I sacrifice myself if the fruits of victory go to others?” In Russian society, the feeling of injustice was directed against various businessmen and the nouveau riche making money out of contracts, as well as against what they saw as talentless state officials and military commanders, whom they blamed for rising prices and failures at the front. And finally, all this dissatisfaction was focused on the man who held supreme power, the Emperor Nicholas II. It is quite striking that after two years of war, public opinion among virtually all of educated society was against him, and even the monarchists were saying that if the monarchy was to be saved, the monarch would have to be removed from power.

The first instances of certain units refusing to go on the offensive occurred as early as autumn of 1916. It is not surprising that after the February events, there was a sharp decline in the troops’ discipline, fighting spirit and willingness to sacrifice their lives. Attempts to rescue the situation by introducing capital punishment, creating “assault units” (thereby creating an institutional division between battleworthy and non-battleworthy soldiers) and “carving out” legitimacy through the system of military committees and active propaganda failed to bring the desired results. Large-scale transfers of senior officers resulted in new authorities appearing in all the senior command roles, who might well have distinguished themselves earlier, but who nevertheless needed time to establish themselves with their new responsibilities. The problem of injustice had also not been resolved among the troops. Some small but eloquent examples can be found in the documentation of the 11th Army. At the end of April, soldiers of the 7th Finnish Rifle Regiment, who were being withdrawn to the rear, refused to take part in exercises, demanding that they be allowed to keep this time for rest and recovery and declaring, “if they think we’re not ready for combat, let them withdraw us right into the rear”.[1] In mid-May some units of the 6th Turkestan Regiment resisted attempts to transfer them to a new area on grounds that they had insufficient machine guns, depleted ranks, and no light clothing. The 6th and 7th Turkestan Regiments soon refused to relieve units of the Guards Division (the Pavlovsky Regiment and the 2nd Guards Rifle Regiment) at the front until the latter got its trenches prepared. In other cases, the reason for disobedience was the meagre food supply. In May, for example, General Alexei Gutor sent a very characteristic telegram to the headquarters of the South-Western front: “presenting herewith the report of the 17th Army staff for May 5, No. 1002, and fully in agreement with its content, I request that all steps be taken to meet the most essential material needs of the army, i.e. food, footwear, clothes and underwear, as quickly as possible, and thereby to eliminate the most severe need before it becomes strikingly obvious.” [2]

The Kornilov Mutiny damaged the proposed alliance between the Provisional Government represented by Kerensky and the top military commanders. The minister-chairman won a Pyrrhic victory: the generals whose names were, not without reason, linked to the revival of the army’s combat readiness were arrested. The army continued to decay, and Kerensky’s loss of this powerful backing led to the success of the Bolsheviks’ October uprising. It would be a mistake to consider that the whole army was on their side at this moment, but on the Northern and Western fronts they had far greater support than on the South-Western front and in the Caucasus. In the context of the battle for the capital this was of decisive significance.

The Bolsheviks associated the Decree on Peace not with ending the war so much as with turning it into a global revolution. The Germans agreed to hold talks on terms of “peace without annexation and reparations”, although they noted that they were prepared to consider this option only if all the warring parties took part. Both sides were undoubtedly adopting hypocritical stances: the Germans were trying to impose the most onerous conditions, while the Bolsheviks were using the talks as a platform for revolutionary propaganda, and they themselves were dragging the process out, hoping for a revolutionary crisis to grow in Germany and in the Entente countries. Given that the peoples were tired of war, the Germans had a food crisis and the workers’ movement was gathering strength, these hopes were not unfounded. The problem was that the Bolsheviks did not have an army capable of waging a revolutionary war at their disposal. Moreover, as early as the end of 1917, the army in the field had begun to rapidly demobilise, and this was supported by the November 10 (23 in the old style) decree on a gradual reduction of the size of the army. In parallel with this, a delegation from the Ukrainian Rada [parliament] joined the negotiations, which gave German diplomacy more room for manoeuvre. As soon as they had concluded a peace treaty with this delegation, the Germans hardened their position and gave an ultimatum which was rejected by Trotsky. Or rather, that was when he proposed the formula of having “neither war nor peace” and disbanding the army. He managed to send an order to Ensign Krylenko, the Bolshevik commander-in-chief, to carry out complete demobilisation, but then Lenin cancelled it. The Germans interpreted Trotsky’s position as a rejection and launched a large-scale offensive (Operation Faustschlag) on February 18, 1918. The show of strength had the desired effect: Lenin made concessions and signed a treaty on even more difficult terms than those that had been discussed previously. As a result the Brest Peace Treaty could only be called “shameful”. [3]

The actual signature of the treaty led to a political crisis: the Left Socialist Revolutionaries left the government (the Council of People’s Commissars), and the Left Communists (headed by Nikolai Bukharin) came out against the treaty, but a schism in the party was averted thanks to the hard work of Yakov Sverdlov. They regarded the Brest Peace as a concession to German imperialism, a rejection of the ideals of world revolution, and the “surrender” of their comrades in Ukraine. [4] Some local soviets even adopted resolutions calling for the treaty to be abrogated and expressed fears of a return to rule by the tsar and landowners. There was no unity with regard to the Brest Peace Treaty among Russian industrialists either: some actively cooperated with the Soviet authorities on the question of nationalisation, while others were more positively inclined towards peace with Germany (especially those who in the summer and autumn of 1918 had fled Soviet Russia and started entrepreneurial activity in independent Ukraine). Yet others took a negative view. [5] Even the counter-revolutionary Right Centre, which had been set up in Moscow (and which engaged in support for the incipient White movement in the South) was divided over this issue. Some members of the Constitutional Democratic Party considered the possibility of lending temporary support to the Bolsheviks in the context of the inevitable external threat. [6]

It is worth noting that both Lenin and the Germans were well aware that many of the peace terms were somewhat symbolic. For example, neither side halted its propaganda on the other’s territory, and by the spring-summer period German forces had already begun to move gradually eastwards, taking Crimea and Rostov-on-Don. Many undoubtedly saw this as weakness on the part of the Bolsheviks and believed that the gains of the revolution were being lost. But the situation changed in autumn, when the Central Powers were defeated. Revolution broke out in Germany in November 1918, the Compiègne Armistice was signed on November 11, and just two years later Soviet Russia abrogated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in the Soviet historical narrative

During the period after the Civil War, when current political events became history, the Brest Peace Treaty proved to be the point of intersection of two significant theses which legitimised Soviet power: the anti-militarist position of the Bolsheviks (who had fought from the beginning for an end to the imperialist war waged only in the interests of big business) and the idea of enemy encirclement (it was German imperialism that had put the world’s first “workers’ and peasants’ state” in a most difficult position by imposing a dishonest and extortionate peace). Moreover, the blame was shifted onto the Entente and the USA, since it was they who had rejected Lenin’s appeal for peace and therefore ensured that only separate negotiations could be held [7]. It is not surprising that in the context of the political conflict of the 1920s and 1930s and the repressions, recollection of the former Left Communists’previous position turned into a regular political argument and an accusation of opportunism, which very nearly cost the life of the Soviet regime. After the Great Patriotic War, the patriotic line of interpretation of the events in 1917 began to gain strength: the tsarist and Provisional governments were accused of pursuing an anti-popular policy, while the Bolsheviks were portrayed as the ones fighting for the interests of the people. Naturally, mention of their role in the army’s collapse in 1917 was avoided, and the Brest Peace Treaty was represented as a step the country was forced to take.

It would be no exaggeration to say that in the official Soviet historical narrative the First World War was a war that never ended. It did not have its own “identity”, becoming a catalyst for objective socio-economic conflicts and the “zero point” of the 1917 revolution. All the events after February 1917 were regarded not as part of the First World War itself, but as part of the revolution and the Civil War. As if by a wave of the hand, the First World War (which itself was portrayed as a series of defeats and failures) was left behind in the old autocratic world; it was squeezed out of the history of the new world, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk itself was nothing more than one of the stages which the Bolsheviks had to pass through on the road to the socialist future. Thus, the formation of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army (RKKA) by a decree on February 23, 1918 was regarded as part of the history of the Civil War, even though these events were linked with the Germans’ attack on Pskov.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in the White émigré historical narrative

Another alternative narrative regarding the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the end of the First World War is associated with the émigré historiographical tradition. Here there is undoubtedly an end point: November 11, 1918, the day on which the Compiègne Armistice was signed. This date is now a key event in the memorial calendar of many countries, and Russia is no exception. It may be recalled that when some government representatives and social activists in Kaliningrad Region began to hold events in memory of the “forgotten war” in the 2000s, this was the date they chose. Even after this, when August 1 became the official Remembrance Day at the federal level in accordance with a decision by the State Duma in 2013, the date of November 11 was not entirely lost. Thus, for example, the Russian Military Historical Society regularly organises a wreath-laying ceremony at the memorial for the heroes of the First World War at Poklonnaya Hill on this day. At the symbolic level, this is an attempt to restore historical justice, and in effect to say that Russia should not be written out of the history of the First World War, and its contribution should not be written out of the overall victory of the Entente.

In this context the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty is seen not as a step that Russia was forced to take, but as an act of betrayal of the country’s national interests, betrayal of the efforts of the Russian army and of the sacrifices it made. The first people to champion this point of view were the Russian officers who formed the backbone of the White movement. The Bolsheviks’ seizure of power was regarded as illegitimate (especially after the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly), as was their right to sign such international documents. By no means all of the alternative “white” governments recognised the Brest Peace Treaty with Germany: for example, in the South the leadership of the Volunteer Army headed by Anton Denikin did not recognise the peace treaty, and the Provisional Siberian Government formed in the summer of 1918 announced its close links with the Entente. The Ufa Directory, which was set up in September, stated unequivocally that it did not recognise the Brest Peace Treaty. Moreover, individual battles were fought in the spring of 1918 on the Caucasian front and in Persia, and some of the heroes of these engagements were the last in the First World War to be awarded the Cross of St. George [8].

In addition, Russian soldiers from the so-called Russian Expeditionary Force remained in France. About a thousand of them formed the Russian Legion of Honour. In the spring of 1918 the 1st Battalion was attached to the Moroccan Division, with which it initially took part in the defeat of a major German offensive. In the summer it was reformed along the lines of the French Foreign Legion: its numbers were brought up to 900 men, and Major Tramuset became its commander. In this form the battalion fought with distinction during the breaking of the Hindenburg Line in September 1918. In October General Philippe Pétain decorated the Russian Legion of Honour with the Croix de Guerre with palm, and the heroism displayed by this unit allowed it to take part in the November celebrations in honour of the end of the war. Curiously, one participant in these battles was Corporal Rodion Malinovsky, a future Marshal of the Soviet Union. For his involvement in these actions he was awarded the French Croix de Guerre and the Russian Cross of St George, third class [9].

The question of whether these soldiers were the last defenders of their country’s honour or simple mercenaries is a contentious one which depends on one’s view of the Bolshevik government’s legitimacy and of an ordinary person’s connection to the state. At the same time, it is obvious that for many Russians, the First World War certainly did not end on March 3, 1918. Moreover, the concept of the “lost victory”, according to which Russia’s generally successful course of action during the First World War was artificially cut short by the revolutionary upheavals of 1917 and the country was deprived of victory by various revolutionaries, had already begun to take hold among military émigrés. Those who wanted to deny the objective character of the revolutionary upheavals and the collapse of the army had to seek other explanations, which could be found only in the field of conspiracy theory. And the Civil War itself became effectively a continuation of the First World War.

1. Russian State Military Historical Archive, holding 2148, catalogue 1, file 979, p. 38.

2. Russian State Military Historical Archive, holding 2148, catalogue 1, file 981, p. 20.

3. P.V. Makarenko, “The Bolsheviks and the Brest peace treaty”, Voprosy Istorii, 2010, No. 3, pp. 3-21.

4. S.S. Voytikov, “‘Opposition in one’s own home’: Defeat in the First World War and ‘national’ cohesion in the ranks of the Bolshevik party, 1918,” Noveyshaya Istoriya Rossii, 2014, No. 3, pp. 218-233.

5. M.K. Shatsillo, “Russian business circles’ reaction to the Brest peace treaty, 1918”, Vestnik RUDN, Series: History of Russia, 2010, No. 1, pp. 105-117.

6. Cf. F.A. Seleznev, “The question of a separate peace with Germany in the context of the struggle of the Russian elites (1914-1918)”, Vestnik RFFI, 2017, No. 1, pp. 22-31.

7. A.V. Pantsov, “The Brest peace treaty”, Voprosy Istorii, 1990, No. 2, p. 60.

8. A.V. Kuzmin, G.N. Mazyarkin, D.N. Maximov, V.L. Yushko, Chevaliers of the Military Order of St George the Great Conqueror and Victor in the period 1914-1918, Moscow, 2008, p. 8.

9. Cf. A.Yu. Pavlov, The “Russian Odyssey” in the Era of the First World War: Russian Expeditionary Forces in France and the Balkans, Moscow, 2011, pp. 130-140.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |