When Friends Can’t Agree

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in History, Associate Professor, Department of Post-Soviet Countries, Russian State University for the Humanities, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Post-Soviet and Interregional Studies

The foreign ministers of Russia, the Federal Republic of Germany, France and Ukraine met in Berlin on 21 January, 2014. The “Normandy format” meeting of the foreign ministers took place in the context of escalating armed conflict in the Donbass region. The talks in Berlin were effectively the last chance of a peaceful settlement, and if this failed the likelihood of a further escalation of the conflict would be guaranteed.

The foreign ministers of Russia, the Federal Republic of Germany, France and Ukraine met in Berlin on 21 January, 2014. Their talks were held in the so-called Normandy format, named after the place where the first meeting of the heads of the four countries’ governments after the start of the Ukraine crisis took place on 6 June 2014. At the end of the talks Sergei Lavrov, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Laurent Fabius and Pavlo Klimkin managed to agree a statement on the withdrawal of heavy weapons from the demarcation line established by the Minsk agreement of 19 September, and also on stepping up the work of the contact group. “The most important decision taken today is powerful support for the objective of rapidly withdrawing heavy weapons from the demarcation line specified in the Minsk agreement,” Sergei Lavrov told Russian journalists at the end of the meeting [1].

The Minsk agreements – new implications of unfulfilled points

Both sides regarded the Minsk agreement as a breathing space and used it as an argument in their information campaigns.

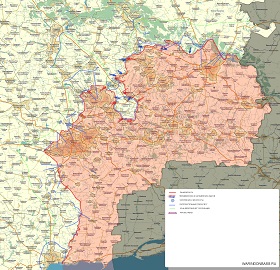

The “Normandy format” meeting of the foreign ministers took place in the context of escalating armed conflict in the Donbass region. During the constant fighting of the previous days the DPR and LPR militias had managed to seize the initiative and by using a significant amount of armoured vehicles and artillery to capture a large part of Donetsk airport and a small amount of ground in the region of Stanitsa Luganskaya, and also to signal their serious intention to attack Mariupol and Debaltsevo [2].

The January surge in military action demonstrated a few important points. First, the West’s expectation that Russia, cut off from European and US credit and experiencing a serious economic crisis, had already lost the conflict not only strategically but also tactically and was ready to “surrender” the DPR and the LPR without laying down any serious conditions proved to be illusory.

Second, the Minsk agreements, which all sides have been saying were needed since the moment they were signed, have finally ceased to be implemented. The Minsk agreements have definitely played something of a positive role in the attempts to resolve the conflict, and in the context of large-scale military action they facilitated a marked reduction in the intensity of the fighting, and consequently thanks to them many lives were saved. They were especially beneficial to the Ukrainian side, since they were signed after Kiev’s military defeat in August 2014.

In addition, the first dialogue between Kiev on the one hand and the DPR and LPR on the other took place in the Minsk format, albeit not at the very highest level. However, that’s probably about as far as the importance of the Minsk agreements goes.

In this situation the talks in Berlin were effectively the last chance of a peaceful settlement, and if this failed the likelihood of a further escalation of the conflict would be guaranteed.

For Russia, which had lost the initiative on Ukraine in the autumn as a result of the economic crisis and the sanctions which were having an increasing impact on the economy, they were definitely a political retreat. This is especially true of the points about holding elections in the DPR and LPR according to Ukrainian legislation and the need to hand control of the border to Ukraine. Implementing these points in the literal meaning of the word would lead to effectively handing Kiev control of the self-proclaimed republics. That’s why Moscow, having signed the Minsk agreement, allowed the elections in the DPR and LPR to be held without Ukrainian agreement, and Ukraine in turn, under the strong influence of the USA, set about rearming and reorganising the army and did nothing about withdrawing heavy weapons. Thus both sides regarded the Minsk agreement as a breathing space and used it as an argument in their information campaigns. Kiev declared that it was peace-making, while actually strengthening its military infrastructure, and did not regard the agreements as a binding document at all.

Third, it is obvious that on the one hand the DPR and LPR’s military forces have been seriously strengthened, and on the other, some positive changes have also happened in the Ukrainian armed forces (ZSU). While the latter are experiencing serious problems in terms of equipment, in operations they are no longer the disorganised mass that they were to a large extent during the August fighting. The ZSU can now contain the militia forces, although they are not capable of a serious offensive. The DPR and LPR militias in turn are also incapable of organising a large-scale offensive without serious help from Russia.

The first dialogue between Kiev on the one hand

and the DPR and LPR on the other took place in

the Minsk format, albeit not at the very highest

level. However, that’s probably about as far as

the importance of the Minsk agreements goes.

Fourth, the Russian authorities’ perception of the economic situation is such that there is not yet any question of a significant easing of its stance in the face of the West’s consolidated pressure. The Russian leadership is well aware that when the US president spoke in Congress and described the Russian economy as being in a state of severe crisis, he was clearly exaggerating the importance of the sanctions, which are having a negative but only secondary impact in comparison with the fall in the oil price. Moreover, the economic crisis in Russia began back in 2012, and even then it began to show in a reduction in growth rates, energy use, rail transport levels, etc. The crisis phenomena later led to a reduction in the rouble’s exchange rate, the collapse of which really happened in December 2014, but whose gradual fall relates to the beginning of last year. Thus the crisis in the economy is caused primarily by the actual structure of the economy and by issues concerning the quality of management and the level of monetary policy, and it started when oil prices were high, while the present exacerbation is simply a natural development of crisis trends in the context of sanctions and low oil prices.

Thus with Russia still facing the consolidated stance of the West, in January 2015 the country raised the stakes still higher when it saw its Western opponents’ reluctance to make serious concessions over Ukraine and was concerned that Ukraine might attempt to stage a Serbian Krajina scenario. As a result the situation effectively reverted to the one that we saw in summer 2014 – to large-scale military action along virtually the whole front line. The key issue was thus the front line, the demarcation line between the two sides.

From this point of view the attempt to seize Donetsk airport in January 2015 in response to the systematic firing on Donetsk can be seen in two ways. On one hand, it is an attempt to deprive Ukraine of its advantage in morale and of the opportunity of making heroes of its soldiers by debunking the myth of heroic cyborgs and a “Ukrainian Thermopylae”. On the other hand, it is a clear attempt to push the front line away from Donetsk. Donetsk airport, however, especially given the current state it’s in, is far from being the chief strategic point on the front line. Mariupol, Debaltsevo and Stanitsa Luganskaya are much more important points. It’s no accident that they have also featured in military reports in recent days. Without control of these places the DPR and LPR are markedly more limited in their opportunities in terms of infrastructure. The reason why the militias have been so active in the January fighting is because they want to move the front line farther to the west and north.

In this situation the talks in Berlin were effectively the last chance of a peaceful settlement, and if this failed the likelihood of a further escalation of the conflict would be guaranteed. The ministers’ meeting was undoubtedly of a technical nature. It should have preceded a “Normandy format” meeting of the heads of state in Astana, but this meeting is in doubt. This is entirely understandable, since the heads of state must conduct their talks from previously known and to some extent agreed positions. Otherwise the image impact will be negative, and it will not be possible to resolve any practical issues. In this context the meeting of the ministers in Berlin was in a preparatory format and agreed only one point, which is essentially political in nature – the point about withdrawing the two sides’ heavy weapons.

Prospects of a settlement

If the point about withdrawing heavy weapons is implemented it will probably enable the heads of state to have a “Normandy format” meeting, and in the longer term it could become the starting point for a peace settlement process through freezing the conflict.

If the point about withdrawing heavy weapons is implemented it will probably enable the heads of state to have a “Normandy format” meeting, and in the longer term it could become the starting point for a peace settlement process through freezing the conflict. There are many obstacles on this road, however, which mean we cannot talk with any confidence about the stability of a settlement. A “freezing” of the conflict in Donbass, even if such a scenario is implemented, will be seriously different to the “freeze” that we can observe in Transnistria or Nagorno-Karabakh. The difference is that in this conflict the stakes for Russia are too high, and it is taking place not simply in the context of rivalry between the West and Russia in the post-Soviet area, but also in the situation of a serious mental break between Europe and the USA on the one hand and Russia on the other. An example of this, which while limited, is also very characteristic, can be found in the statements by the Polish foreign minister about the liberation of the Auschwitz camp. Moreover, for Russia the question of south-east Ukraine is tied to the problems of sanctions and Crimea. Yes, Russia has given up the idea of Greater Novorossiya, at least for the time being, but nevertheless it is not receiving any serious signals from the West about the possibility of concessions on Crimea. The signals about the likelihood of the sanctions being divided into a “Crimea” package and a “South-East” package are apparently not regarded as sufficient for serious reciprocal concessions, especially as they are not coming from Washington, which showed last year the continuing strength of Euro-Atlanticism. The distinguishing feature also lies in the limited nature of opportunities for potential influence on Ukraine by Moscow, which is increasingly boiling down to military and political pressure for both objective and subjective reasons. In the last year alone the two countries have taken a colossal journey of disintegration, which is strategically unfavourable to Russia, which declares its special role in Ukraine.

Moscow continues to insist on a dialogue within Ukraine between the authorities in Kiev and the current leaders of the DPR and the LPR, i.e. it is trying to legitimise the leadership of the self-proclaimed republics, which was elected, incidentally, in contravention of the relevant point in the Minsk agreement. Kiev can thus start to insist on new elections in the region, which even if the two sides agreed would immediately raise the question of votes for refugees, technical support for the procedure, accuracy of vote-counting, etc.

In addition, during these hypothetical further systematic talks the question of who the South-East territory belonged to in reality rather than in words would also arise. Moscow frankly states that the South-East should remain part of Ukraine, and frequently mentions extensive autonomy, but in reality, even if autonomy is granted there are no guarantees that Kiev would in future allow the current leadership of the South-East to have a serious influence on the domestic political situation and on foreign policy, and therefore Russia will immediately defend at least the temporary non-aligned status of Ukraine itself. In this context the question of whether Kiev will be able to bring its army and militia into these regions arises, since without this there can be no talk of a fully-fledged reintegration.

Even if autonomy is granted there are no guarantees that Kiev would in future allow the current leadership of the South-East to have a serious influence on the domestic political situation and on foreign policy

Through its active work to prevent a feud in the DPR and the LPR Russia is keeping these republics under control and maintaining internal discipline by providing support to keep supporters of Plotnitsky in power in the LPR and those of Zakharchenko in the DPR, and the question of what to do with the militia in the self-proclaimed republics arises. Russia will probably insist on the demilitarisation of the region and on the presence there of collective security forces, with local self-defence being maintained for a certain period, even if in a limited form in comparison with today’s militia. Russia will probably, despite the relevant point in the Minsk agreement, try to get a change in the point about the border, since this is a key aspect in terms of support for the South-East. Serious differences in all these areas are entirely capable, especially if external forces do not resist, of leading to a new exacerbation of the conflict and to Russia being accused by the West, which has latched on to the Minsk agreement while being fully aware that a frozen status according to its points does not suit Moscow at all.

We should also note the importance of the information component and style of decision-making. It is symptomatic in the context of the meeting in Berlin that Russia stated through the head of its foreign policy department that secret agreements concerning the demarcation line between the two sides exist [3]. In particular, it was said that according to these agreements it was the militias who were supposed to control Donetsk airport. In itself the possible fact of secret agreements does not raise any questions, but up to now Russia has not precisely formulated, even in outline, its position regarding many aspects of a peace settlement, and has not provided a precise peace plan, even as a supplement to the Minsk agreement, alongside the general demands for autonomy and constitutional reform.

Serious differences in all these areas are entirely capablet of leading to a new exacerbation of the conflict and to Russia being accused by the West, which has latched on to the Minsk agreement while being fully aware that a frozen status according to its points does not suit Moscow at all.

This will probably be done if Normandy-format summit meetings take place, but it is obvious that without this Russia is more likely to lose out, including in terms of image. In the course of a peace process Russia will also probably make certain mitigating corrections in the area of information policy, although Ukrainian subject matter, especially in the context of the economic crisis, will continue to be one of the top areas of interest in the media, playing the role of a kind of lightning conductor.

Overall the question of the economy will be to a large extent definitive if the western sanctions are maintained and if at the same time a long process of talks begins. At the same time both sides are counting on serious economic losses for each other, and consequently the situation is distinguished by the fact that the economic position in both Russia and Ukraine is becoming a serious factor in the political process.

Presidential Press Service

Sergey Utkin:

The Ukrainian Crisis: Russia’s Official Position

and How the Situation Can Be Resolved

Thus it is possible to state that the peace process itself will be optimal if it combines elements of all formats – the Geneva, Minsk and Normandy formats, but in present conditions the Normandy format makes it possible at least to move closer to a possible start of a systematic settlement and become the superstructure for an internal Ukrainian dialogue. A return to the Geneva format in the strict sense of the word will make the situation more difficult for Moscow, since it will not simply bring the USA, which takes a plainly anti-Russian position in the Ukraine conflict, back into the talks, but also take France and Germany out of them. Europe will be represented by Brussels, which is also not very favourable for Moscow.

We should not talk today about a rapid freezing of the conflict, but instead we should assert with a high degree of confidence that both sides are capable of maintaining their positions in a negotiating process. The situation, however, is gradually becoming such that the direct losses, both military and political, from the conflict, as well as the economic problems, are becoming so serious that a constant game of raising the stakes between the two sides could lead to irreversible consequences, and the emotional and psychological element should also not be overlooked. Those involved in the conflict and external players realise this, even despite the fact that many on both sides are not averse to trying to achieve more than is really possible. This is the context in which the statements by Germany’s foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier that “the two sides’ patience is at its limit” should be considered.

However, in any case the success of the peace process depends on what concessions the two sides, primarily the West, are prepared to make, since Moscow will clearly not agree to a unilateral retreat on the South-East without serious halfway steps in the form of a serious reduction of the sanctions and the non-aligned status in various forms. So far, there is no sign that the West seriously intends to take such steps.

1. http://rian.com.ua/russia/20150122/362383595.html

2. http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/news/2015/01/28/n_6869041.shtml

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |