The installation of a new government in New Delhi in May 2014 inevitably set off speculations about how this event would impact India-China relations. The meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the BRICS summit at Fortaleza in July 2014 was marked by a positive atmosphere and raised expectations of a breakthrough in bilateral ties.

However, there are many obstacles to overcome before New Delhi and Beijing can enjoy a trouble-free relationship. The most important of course is the border dispute between the two countries.

The turmoil in Tibet, which began when Tibet forcefully became part of China in 1951 and then later included the subsequent escape in 1959 of the Dalai Lama to India, led to a considerable deterioration in bilateral relations. Tensions culminated in the Chinese attack in 1962 when India lost vast territories to China.

The two countries share an almost 4000 km long border. There are disputes between them over three areas along their borders: in the Eastern Sector along the Himalayas (along the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh), in the Middle Sector from the tri-junction between the Southwestern of Ngari Prefecture, Tibet, La dwags and Punjab to the tri-junction between China, India and Nepal, and in the Western Sector pass of Karakoram in the North to the tri-junction between Tibet’s Ngari Prefecture, La dwags and Himachal Pradesh [1].

Since the end of the 1962 war, despite intermittent tensions, the Sino-Indian border has remained very secure, with no exchange of fire for over four decades. Instead, what has contributed to the tensions has been the “depth perception” problem: India and China view the border differently. On occasion, China sinks to lower depths than it is acceptable, leading to stand-offs like the one in Depsang in 2013.

Efforts to resolve the border dispute have not brought any positive results so far. However, the two countries almost reached an agreement twice. The first time was in 1979 when Deng Xiaoping talked of a swap, with India making concessions in the West and China in the East [2]. But India refused to accept this and insisted on the withdrawal of Chinese troops from the border as a precondition for border talks. Subsequently, New Delhi and Beijing almost reached an agreement with a warning that it would not involve the shift of major population centres across borders. India interpreted this statement as the following: areas like Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh would remain in India. However, since then, the Chinese have moved away from this position and now lay claims on Arunachal Pradesh, which they refer to as Southern Tibet.

Though they have failed at resolving the border dispute, Beijing and New Delhi have shown the maturity to put the problem to the side and move ahead on cooperation on other issues. The two sides have a joint working group on border issues, which has held several rounds of talks and is currently negotiating a framework for the resolution of the boundary questions. They have also signed a border defence cooperation agreement and are negotiating a code of conduct for troops along the Line of Actual Control.

India has made several concessions to China in order to establish amicable relations. For instance, India recognises the One China policy. Taiwan only has a cultural centre in India and not a diplomatic mission. Second, India now recognises the Tibetan Autonomous Region as a part of China. Third, though India has given asylum to the Dalai Lama and his followers, it does not allow them to conduct any political activities against China. However, the Chinese have, so far, not responded with similar gestures. For example, China continues to view Kashmir as disputed territory.

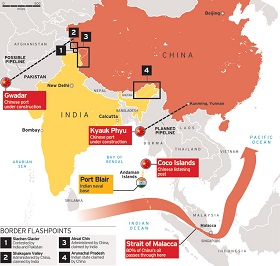

Another point of friction which has somewhat cooled in recent times, is China’s alliance with its all-weather friend, Pakistan. In the past, China has not been averse to using Pakistan as a second front in its rivalry with India. China's involvement in Pakistan's nuclear programme has also been of particular concern in India. According to several accounts, it aided Pakistan's military nuclear programme and currently is offering to upgrade Pakistan's civil nuclear sector. However, recent terrorist activities in Northwest China, seem to have highlighted the perils of embracing Pakistan too closely to the Chinese establishment.

The questions of China issuing stapled visas to Indian citizens from Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh and Chinese maps showing parts of India’s territory as being part of China in recent years have not helped the relationship.

On the other hand, since economic liberalisation, trade has taken off between the two countries. China is India’s biggest trading partner and India is China’s largest trading partner in South Asia. In 2013, trade between India and China was about $66 billion. The two countries are targeting a level of bilateral trade worth $100 billion by 2015. Chinese investments in India stood at around $576 million in 2011.

India has a huge trade deficit with China ($31.4 billion in 2013). This is an issue of concern for New Delhi and a challenge that must be dealt with. China has not been enthusiastic about granting market access to Indian goods as well as investments, particularly in the pharmaceuticals and IT industries. India, on the other hand, has also not been particularly welcoming to Chinese investments in some infrastructure projects.

Furthermore, India is concerned about cheap Chinese goods flooding its markets, which has prompted it to file several anti-dumping cases against China and increase tariffs on some products. Moreover, while much of India’s exports to China consist of raw materials like iron ore, cotton and copper, China’s exports to India are made of sophisticated equipment and electronics. For Beijing, the issue at hand are the delays in getting project approvals, granting business visas and removing investment restrictions on some sectors. Despite this, trade with China, particularly border trade, seems poised to grow in the coming years.

It must be noted that both countries have similar views on the current system of global governance and want emerging powers to have a greater say. Therefore, the two countries are also engaging in several multilateral frameworks where they are trying to reach a common understanding over regional and global problems. The BRICS is an example of Sino-Indian cooperation. They are also engaged in Russia-India-China trilateral negotiations and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The security situation in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of US troops is something which worries both countries, who have begun consultations on the issue. They have similar concerns in Central Asia as well.

Among other causes for concern, however, are China's policies in South Asia, which India views as detrimental to its pre-eminence in the region. Similarly, China has reacted with hostility to India's involvement in the South China Sea. Finding a better understanding at a time when both powers are rising is vital if the two are to contribute positively to the development of Asia and the world.

India and China have a vital interest in securing Asia’s security and development. This is linked to the primary goal of the Chinese and Indian leaderships to ensure prosperity for their peoples, which means they need to provide adequate infrastructure, health, education, skills, and jobs.

Thus, India and China face similar challenges domestically and externally. The fact that at least for the next five years, India will have a stable government and that Xi Jinping appears entrenched as China’s leader for the next decade should also help move the relationship forward.

However, the depth of the relationship and how far it will go would depend on the ability of the two countries to reach an amicable solution to the border dispute.

1. Hongzhou Zhang and Mingjiang Li, ‘Sino‐Indian Border Disputes’, Analysis No. 181, June 2013, http://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/analysis_181_2013.pdf, p.2.

2. Hongzhou Zhang and Mingjiang Li, ‘Sino‐Indian Border Disputes’, Analysis No. 181, June 2013, http://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/analysis_181_2013.pdf,p.6.