What does the post-Brzezinski era hold for the future of the U.S. role and its geostrategic imperatives in an ever more polarized world?

In

Log in if you are already registered

There is no doubt that on May 26,

Zbigniew Brzezinski was a man who in the course of his long and rich academic, policy and public life earned a different meaning to different people.

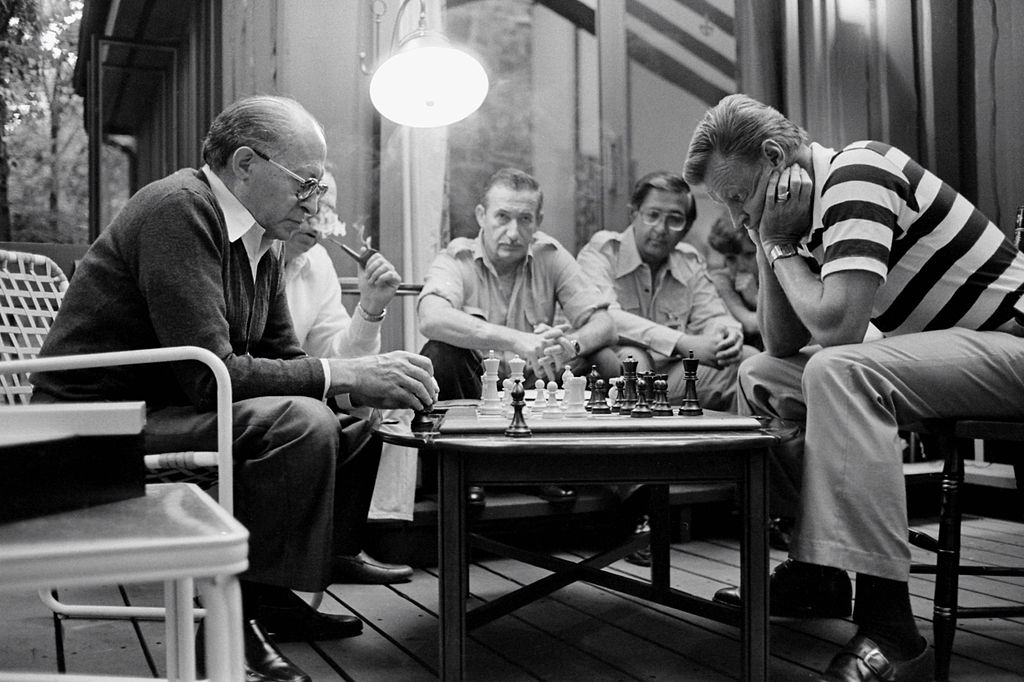

Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin engages U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski in a game of chess at Camp David

“Zbigniew Brzezinski, the hawkish strategic theorist who was national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter

To the

In Mika Brzezinski’s own words, to whom I want to extend my deepest condolences, her father “was known to his friends as Zbig, to his grandchildren as Chief and to his wife as the enduring love of her life.” As we can also find out from her Instagram post, for herself, he was “the most inspiring, loving and devoted father any girl could ever have.”

“

“Poland lost a great ally and guide. No successors can be seen on the horizon,” wrote a prominent journalist Bartosz Weglarczyk in his article for Onet.pl web portal.

However, how Professor Zbigniew Brzezinski is perceived and will be remembered by my generation of young people who were born in

Like most of my contemporaries, I am perfectly aware that Zbigniew Brzezinski was born in Warsaw on March 28, 1928. His father, Tadeusz Brzezinski, was a diplomat who served as a Polish consul in Canada since 1938, which fact contributed to the younger Brzezinski’s first academic choices, as he subsequently graduated from McGill University and University of Montreal. He later obtained his doctorate from Harvard University, where he defended his dissertation on the history of Soviet totalitarianism. In 1958, he became a US citizen.

Brzezinski started his academic career in

He was later a director of the Trilateral Commission (founded by a famous American banker David Rockefeller, to whom Zbigniew Brzezinski served at some point in the capacity of an international adviser), which is a “non-governmental, non-partisan discussion group” gathering politicians and businessmen wishing to deepen the alliance between the USA, Western Europe and Japan.

Nevertheless, as I came to know in the course of broadening my knowledge in the American political thought, both

Prominent American conservative thinker, and Senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater described the Trilateral Commission in his book titled With No Apologies as “a skillful, coordinated effort to seize control and consolidate the four centers of power: political, monetary, intellectual, and ecclesiastical... [in] the creation of a worldwide economic power superior to the political governments of the nation-states involved.”

On the other hand, Noam Chomsky in an interview for New Left Project, where he referred to

“[The Trilateral Commission] were essentially liberal internationalists from Europe, Japan and the United States, the liberal wing of the intellectual elite. That’s where Jimmy Carter’s whole government came from. [...] [The Commission] was concerned with trying to induce what they called “more moderation in democracy”-turn people back to passivity and obedience so they don’t put so many constraints on state power and so on. In

As I know, Jimmy Carter was invited by Brzezinski to join the Commission and after winning the presidential run appointed him as his National Security Advisor. In this role, Brzezinski was a strong opponent of Secretary of State Cyrus

Brzezinski’s aversion towards Vance, however, can somehow be justified by the fact that the latter was favourably disposed towards the idea of giving concessions to Moscow, as well as

As befits true Cold War warrior, Zbigniew Brzezinski rejected such “acrobatics”, strongly advocating for “strategic deterioration” in relations with the Soviet Union.

He was so zealous in his anti-Soviet attitude that when the Soviets intervened in Afghanistan, Brzezinski decided to support Mujahedins (in fact Radek Sikorski, a former Foreign Affairs Minister in Poland and husband of famous American political writer Anne Applebaum, later followed his footsteps) and provided them with Stinger missiles to shutting down Soviet helicopters. What more, he also assured them that their “cause is right and God is on their side!”

It is therefore even more saddening for me to discover that to Professor Brzezinski the whole ideological language of Western democracy versus Communist enslavement was nothing more than rhetoric, as as we read in his article published in 1992 in Foreign Affairs magazine titled The Cold War And Its Aftermath, “the policy of liberation was a strategic sham, designed to a significant degree for domestic political reasons... the policy was basically rhetorical, at most tactical.”

As a solid support of his statement can serve leaked in the same year by The New York Times document, which “asserts that America’s political and military mission in the post-cold-war era will be to ensure that no rival superpower is allowed to emerge in Western Europe, Asia or the territories of the former Soviet Union.” It also “makes the case for a world dominated by one superpower whose position can be perpetuated by constructive

It then took six years for Brzezinski to expand further the given idea and to draw a plan for sustaining America’s status wished by him for his new country, as in 1998 Zbigniew Brzezinski published his famous magnum opus titled The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy And Its Geostrategic Imperatives, which he dedicated to his students in order “to help them shape tomorrow’s world.”

“The defeat and collapse of the Soviet Union

The author in very detail describes

On that note, it is striking to me to read that the man who was such a fervent opponent of the Soviet imperialism clearly strived to install imperialistic system in his newly adopted homeland, and on many occasions in the book makes references to America’s “global hegemony,” which in his opinion “is admittedly great, but its depth is shallow, limited by both domestic and external restraints.”

According to the famous political scientist, the main obstacle to achieve the imperial glory by America is

“It is also a fact that America is too democratic at home to be autocratic abroad. This limits the use of America’s power, especially its capacity for military intimidation. Never before has a populist democracy attained international supremacy. But the pursuit of power is not a goal that commands popular passion, except in conditions of a sudden threat or challenge to the public’s sense of domestic well-being. The economic self-denial (that is,

Being fully aware of this social fact related to the essence of “democratic instincts,” Zbigniew Brzezinski still advises his students that in order to achieve seemingly unachievable goal they need to gain ultimate control over Eurasia, as it is “the chessboard on which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played” and “power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world’s three most advanced and economically productive regions.”

Having said that, for those who studied more than briefly this work of Brzezinski, The Grand Cheeseboard appears to be very timely book if we consider the subject matter of current tensions (or even animosities) between America and Russia, and pay closer attention to geopolitical pivots which, according to a definition provided by the author, “are the states whose importance is derived not from their power and motivation but rather from their sensitive location and from the consequences of their potentially vulnerable condition for the behavior of geostrategic players.” In Brzezinski’s view “the identification of the post-Cold War key Eurasian geopolitical pivots, and protecting them, is thus also a crucial aspect of America’s global geostrategy.”

An interesting part of the book is dedicated to classification of “critically important geopolitical pivots,” where among South Korea, Iran, Azerbaijan and Turkey, Ukraine (described as “new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard”) seems to be playing the most significant role - bearing in mind its current relevance to the ongoing international security dispute started after the tragic events of 2014 in Kiev.

“Most important, however, is Ukraine. As the EU and NATO expand, Ukraine will eventually be in the position to choose whether it wishes to be part of either organization. It is likely that, in order to reinforce its separate status, Ukraine will wish to join both,” the famous Professor speculates in the book, equally reminding his readers that “if Ukraine is to survive as an independent state, it will have to become part of Central Europe rather than Eurasia, and if it is to be part of Central Europe, then it will have to partake fully of Central Europe’s links to NATO and the European Union.”

Unfortunately, I am not pretty much sure if this strategic plan could meet with any acceptance from any sovereign leader of Russia, as being a realist I do agree with Henry Kissinger’s views that “the relationship between Ukraine and Russia will always have a special character in the Russian mind,” as well as am perfectly aware of the fact that “it can never be limited to a relationship

Whether it be for the historical reasons related to baptism of Rus’ or strategic one related to Moscow’s access to the Black Sea, it is very hard for me to believe that Russia will allow Ukraine to join NATO, and am sincerely convinced that any attempt to go against this logic can meet with very unexpected outcomes not only for America but also, and most probably only, to Central and East European countries and its citizens.

I base my strong conviction with this regard not only on a scientific analysis of this possibility by the prime academic institutions in Poland, but also knowledge of the fact that Vladimir Putin was hugely influenced by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book titled Russia Under Avalanche (Rossija w

Sadly, the influence of the Professors’ views expressed in 1998 had a profound impact not only on many fine foreign policy craftsmen in the

It is a fact that in America his views predominantly gained popularity among neoconservative movement, but in Poland, as it is noted by Professor Andrzej Walicki from

“Poland, on the other hand, has engaged herself in a kind of a moral struggle with Russia, followed by hostile and aggressive symbolic gestures aiming to morally humiliate the Russians, even at the cost of abandoning material benefits that could come in exchange for a more pragmatic policy towards the former hegemon of the region. It has been considered to be naive to recognize in the general assessment of the reasons behind the collapse of the USSR that the main reason was the crisis of

Professor Anna Razny, who is a former chair of the Department of Russian Modern Culture and Director of the Institute of Russia and Eastern Europe at Jagiellonian University in Cracow, shares quite similar views and

In her timely essay titled Who Is In Charge Of The Polish Party of War?, Professor Razny explains that “for the people associated with the Party of War neoconservative theorists are the masters, while the chief strategist and guru is Zbigniew Brzezinski.”

But as the old Polish saying goes: ‘Tylko

In his famous speech given at the Carnegie Council in 2004, Zbigniew Brzezinski warned the audience on “global awakening,” which has been “spurred by America’s impact on the world,” due to the fact of its ability “to project itself outward" and “transform the world,” as well as creating an “unsettling impact.”

According to the scholar, this awakening “is also fueled by globalization, which the United States propounds, favours and projects by virtue of being a globally outward-thrusting society.”

Zbigniew Brzezinski noted that the very process of globalization contributes to

“I see the beginnings, in writings and stirrings, of the making of a doctrine which combines anti-Americanism with anti-globalization, and the two could become a powerful force in a world that is

Three years later, Brzezinski followed up on the previous idea and wrote in The New York Times that, “global activism is generating a surge in the quest for cultural respect and economic opportunity in a world scarred by memories of colonial or imperial domination.”

To the surprise of many, Zbigniew

One year later, on the pages of The American Interest, Professor Brzezinski quite shockingly admitted in his article titled Toward A Global Realignment that the US is “no longer the globally imperial power” and “can only be effective in dealing with the current Middle Eastern violence if it forges a coalition that involves, in varying degrees, also Russia and China.”

On that note, it is worthwhile reminding ourselves that not long before his death Brzezinski crowned his impressive foreign policy legacy with the following statement made at the first Nobel Peace Prize Forum in Oslo, which took place on December 11, 2016:

“The ideal geopolitical response is a trilateral connection between the United States, China and then Russia… As regional uncertainties intensify, with potentially destructive consequences for all three of the major nuclear powers, it is time to think of what might have been and still could be… Regional cooperation will thus require shared wisdom and political will to work together despite historic conflicts and the continued presence of nuclear weaponry, always potentially devastating but even after seventy years still unlikely to result in a one-sided political victory.”

As it has been recently proved, indeed the observation made by Zbigniew Brzezinski in The Grand Chessboard regarding the “attitude of the American public toward the external projection of American power” seems to be on point.

American peoples spirit, as Professor Brzezinski finally accepted in the twilight of his rich life, is strongly leaning towards John Quincy Adams’ philosophy of America, which in his view is “the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all,” as she is fully aware of the fact that “once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom.”

Therefore, in this sad moment of reflection over the grave of Zbigniew Brzezinski, all who were students of this great thinker now have to make a decision which part of his legacy they ought to remember in their attempts to “shape tomorrow’s world.”

“[America’s] glory is not dominion, but liberty,” argued President Quincy Adams, but Professor Brzezinski has left us the choice.

London-based political risk consultant and lawyer. Former chairman of the International Affairs Committee at Bow Group, postgraduate of London School of Economics and Political Science

Blog: Adriel Kasonta's blog

Rating: 1