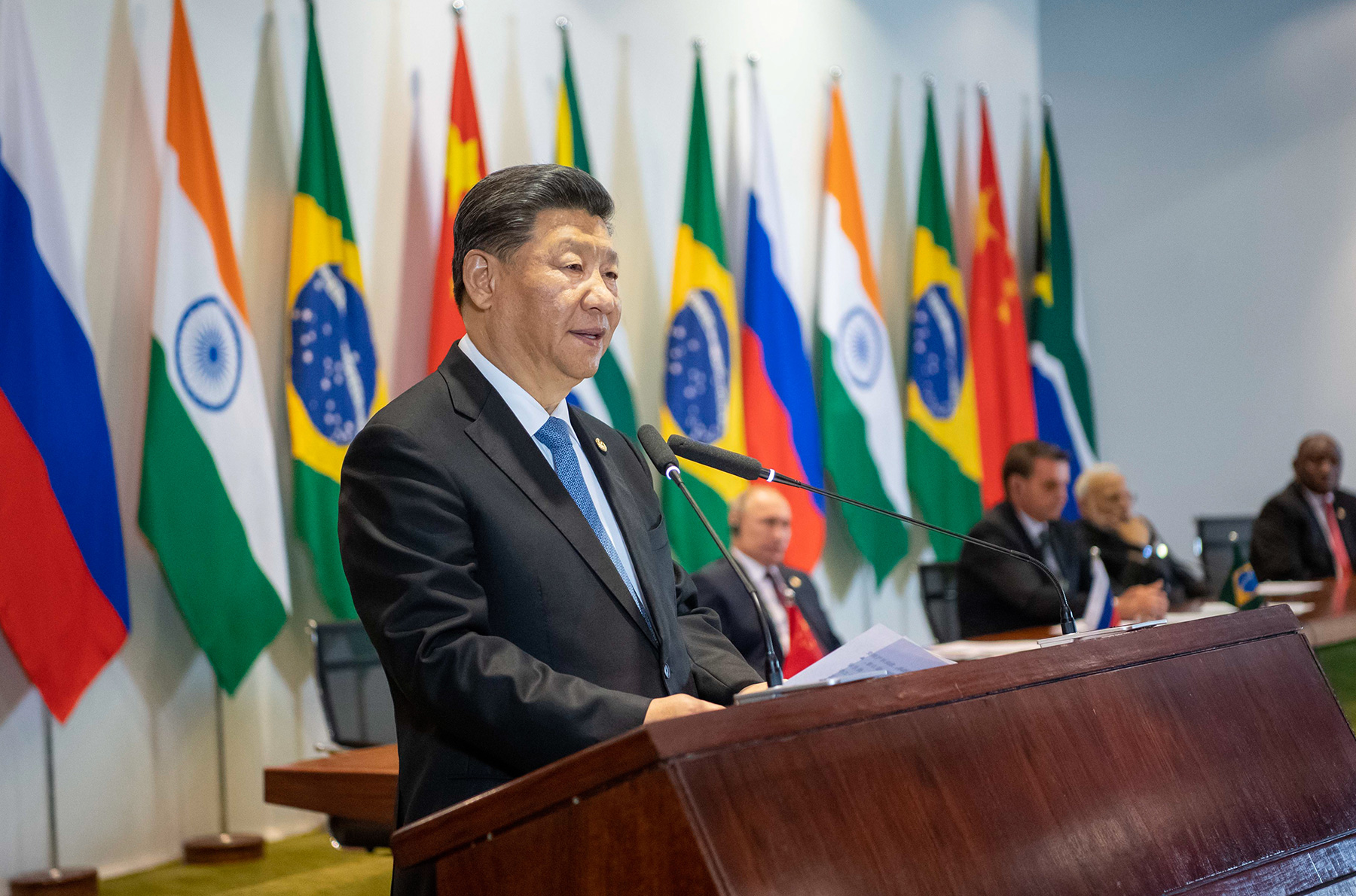

The BRICS summit in South Africa has attracted a lot of international attention — more than such regular events usually receive. Many intriguing questions fed this attention for a couple of months. The interest in the BRICS gathering is understandable — this is the group's first face—to—face meeting at the highest level since the 2019 summit in Brasilia, Brazil. The host — South African President Cyril Ramaphosa — clearly committed himself to giving the event maximum scale and luster by inviting national leaders from 67 countries, including 53 other African states, as well as Bangladesh, Bolivia, Indonesia and Iran, not to mention heads of influential international organizations.

All these situational uncertainties and preparation ambiguities notwithstanding, the most important issue of the 15th BRICS summit is, of course, the likely decisions on new members. Historically, BRICS has been rather reluctant to grow its ranks: Since its inception in 2009, the initial group of the four founders added only one additional member, which is now hosting the 2023 summit. In this sense, BRICS is very different from the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) that has almost doubled its membership since the early days of the original "Shanghai Five" group. However, recently membership inquiries and direct applications have been arriving in large numbers from various corners of the world. With two dozen nations standing in line to join the group, the summit in South Africa might well become a turning point in the history of BRICS.

Nonetheless, deepening with no prospects for broadening creates problems as well. An exclusive club always breeds envy and even resentment from those who are not admitted to the club. Sometimes, those who are not let in, try to start an alternative club of their own. It is no accident that soon after the launch of BRICS an informal alliance of middle powers—Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey and Australia (MIKTA) was created. One of the implicit goals of the new grouping was to serve as a counterbalance to BRICS in generating ideas and proposals for the G20 agendas.

Of course, BRICS does not need to make a clear—cut choice between broadening and deepening — neither at the summit in Johannesburg nor later. A reasonable approach would be to balance the two priorities by opening doors for a gradual rise of membership and concentrating on building the institutional capacity of the group that would help to erase the red line between BRICS members and its partners. In any case, the future of international multilateralism is likely to be defined more by project—based, flexible coalitions of the willing rather than by rigid and heavily bureaucratized blocs and alliances from the 20th century.

The BRICS summit in South Africa has attracted a lot of international attention — more than such regular events usually receive. Many intriguing questions fed this attention for a couple of months. The interest in the BRICS gathering is understandable — this is the group's first face—to—face meeting at the highest level since the 2019 summit in Brasilia, Brazil. The host — South African President Cyril Ramaphosa — clearly committed himself to giving the event maximum scale and luster by inviting national leaders from 67 countries, including 53 other African states, as well as Bangladesh, Bolivia, Indonesia and Iran, not to mention heads of influential international organizations.

All these situational uncertainties and preparation ambiguities notwithstanding, the most important issue of the 15th BRICS summit is, of course, the likely decisions on new members. Historically, BRICS has been rather reluctant to grow its ranks: Since its inception in 2009, the initial group of the four founders added only one additional member, which is now hosting the 2023 summit. In this sense, BRICS is very different from the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) that has almost doubled its membership since the early days of the original "Shanghai Five" group. However, recently membership inquiries and direct applications have been arriving in large numbers from various corners of the world. With two dozen nations standing in line to join the group, the summit in South Africa might well become a turning point in the history of BRICS.

For any multilateral group, broadening presents both opportunities and challenges. By going broader, a group gets additional representativeness and legitimacy. Even today many BRICS leaders take pride in saying that their community accounts for more than a quarter of the planet's territory and the gross world product as well as for more than two—fifths of the world's population. Adding a couple of other large nations of the Global South would make BRICS look even more impressive. The geopolitical opponents of BRICS fully understand the implications of its possible enlargement: It's not surprising that the US leadership cautions its partners in Latin America, Middle East and Africa about applying for BRICS membership.

However, broadening does not come without a price tag attached. More diversity within a group inevitably generates more disagreements among its members, it becomes increasingly difficult to come to a common denominator on some sensitive and divisive matters, which often happen to be the most important ones. At the same time, deepening instead of broadening has its own undeniable advantages and its strong supporters within the BRICS family. Deepening refers to strengthening the existing relationships and cooperation among the BRICS countries, rather than expanding the group by inviting new members. After expelling Russia in 2014, the group of seven leading Western economies has not announced any plans to invite new members, but it has energetically worked on its cooperation infrastructure and its institutional capacities to engage other international actors on the ad hoc basis.

Since it was launched in 2006, BRICS can hardly qualify as a full—fledged multilateral international organization with its own charter, detailed procedures, a permanent physical headquarter or an operational budget. However, some of its institutional initiatives, particularly the New Development Bank, as well as the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, the BRICS Business Council, and the BRICS Academic Forum, have proven to be quite successful. Proponents of deepening call for further enhancing the group's institutional capacity as the very top priority. They also advance the concept of "BRICS+" as an alternative to the membership growth — using the five members scattered across four continents as a wheel hub and their numerous partners as wheel spokes, BRICS could emerge as an open and flexible platform that any country, block or region in the world economy will be able to use in accordance with its specific needs and development strategies.

Nonetheless, deepening with no prospects for broadening creates problems as well. An exclusive club always breeds envy and even resentment from those who are not admitted to the club. Sometimes, those who are not let in, try to start an alternative club of their own. It is no accident that soon after the launch of BRICS an informal alliance of middle powers—Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey and Australia (MIKTA) was created. One of the implicit goals of the new grouping was to serve as a counterbalance to BRICS in generating ideas and proposals for the G20 agendas.

Of course, BRICS does not need to make a clear—cut choice between broadening and deepening — neither at the summit in Johannesburg nor later. A reasonable approach would be to balance the two priorities by opening doors for a gradual rise of membership and concentrating on building the institutional capacity of the group that would help to erase the red line between BRICS members and its partners. In any case, the future of international multilateralism is likely to be defined more by project—based, flexible coalitions of the willing rather than by rigid and heavily bureaucratized blocs and alliances from the 20th century.

First published in the Global Times.