More often than not, China is billed as the driver of post-pandemic global growth and recovery. This claim is not entirely groundless. In addition to combating the pandemic quite successfully, China demonstrated 18.3% GDP growth by the end of the first quarter of 2021, as compared to the first quarter of 2020. Given the current circumstances, there are now concerns that China will have no serious alternatives when it comes to international economic cooperation. For many countries, this situation is fraught with increased dependence on China.

Given China’s much more successful recovery after the pandemic, new avenues lie before it. For instance, China became the EU’s biggest economic partner last year, overtaking the U.S. The number of freight trains travelling between the EU and China topped 12,400 last year, which is 50% more than in 2019 and seven times more than in 2016.

China achieved marked results in its cooperation with Latin American and African nations. In 2005–2020, China’s investment and construction contracts in Latin America totaled some $183 bn. Over the same period, China invested about $303 bn in Sub-Saharan Africa, with another $197 bn in the MENA nations.

Today, China is still trying out its new global status: it continues to promote the value of international cooperation at various international venues, introduce regional trade agreements, set up new global value chains amid the new circumstances.

China’s “warrior wolf” diplomacy often looks like overreaction, and it hurts economic interests more often than not. China’s strategy as a grand concept has long taken shape and is consistently implemented, although quite emotionally. China thinks in categories that entail mandatory accounting for national interests. Most likely, China will continue this policy adjusted for the consequences of the pandemic and for episodes of irrational behavior by international actors. Experience shows that one can and should negotiate with China, no matter how harsh the talks might seem. What ultimately matters in ping-pong is not just reaction time and unpredictability, but also nerves of steel.

More often than not, China is billed as the driver of post-pandemic global growth and recovery. This claim is not entirely groundless. In addition to combating the pandemic quite successfully, China demonstrated 18.3% GDP growth by the end of the first quarter of 2021, as compared to the first quarter of 2020. Given the current circumstances, there are now concerns that China will have no serious alternatives when it comes to international economic cooperation. For many countries, this situation is fraught with increased dependence on China.

Yet, strong economic indicators do not replace the need for regenerating China’s economy after the shocks it has suffered. This is especially so, as the cases of India and some other nations demonstrate that spontaneous outbreaks of the epidemic are still within the realm of possibility and could result in a shortage of vaccines around the world. At the same time, Beijing is facing growing competition with the U.S. as well as unprecedented external pressure exerted by the West.

All these factors taken together raise more and more questions about the trajectory along which the post-COVID world will develop and about China’s global leadership.

Ping-pong diplomacy: a new interpretation

April marked the 50th anniversary of ping-pong diplomacy. Official representatives of China and the U.S. discussed its pivotal role in establishing and fostering bilateral contacts. The parties have come a long way since then—they do not shy away from calling each other ‘principal threats’, with this wording extending to official documents, while the intensity of mutual sanctions exchanges and accusations is, indeed, quite often reminiscent of a ping-pong game.

So far, this looks like a rigged friendly game: no one is really trying to deliver a blow the other could not parry. Nonetheless, as the game progresses, it becomes increasingly appealing, and the political rhetoric of both parties is taking on new colors. The March meeting in Anchorage where the parties exchanged mutual accusations holds a special place in this game.

The parties escaped the confinements of rhetorical displays long ago, as political realities and concomitant practices are changing, too. Last year, China outstripped Russia to come second on the list of states with the highest number of U.S. sanctions imposed against them, while the U.S. is still the principal initiator of such sanctions.

Even more impressive is that military spending is growing amid the global recession. According to SIPRI, it totaled $2 trillion in 2020. Adjusted for the fact that some states (Chile, South Korea) did re-allocate their military spending to other areas, the trend, even if not ubiquitous, will apparently persist. For instance, this dynamic will be relevant for the Asia Pacific. In 2021, China’s military spending grew by 6.8% over last year, reaching $209 bn. South Korea’s military budget increased by 5.4% as compared to last year, reaching $48 bn. Even Japan joined the trend by setting a record in the last few years and allocating about $52 bn to military spending in 2021.

With that in mind, mutual tensions have spread throughout the international relations system. On 6 May, China suspended its strategic economic dialogue with Australia. Earlier, on 22 April, Australia cancelled two deals (between China and the state of Victoria) concluded as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Plans called for cancelling four such deals as being, according to Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne, “inconsistent with Australia’s foreign policy.” New Zealand tends to draw similar conclusions.

Differences in the European area are no less stark, while China sometimes employs an asymmetrically harsh strategy: in late March, in response to four XUAR officials being declared persona non grata, China imposed sanctions on ten Europeans and four organizations. At times, awkwardness emerges even in China’s bilateral relations with those who readily cooperate with China. For instance, there are reports of Chinese hacker attacks on Russia’s Rubin Central Design Bureau of Marine Engineering, which designs submarines for Russia’s Navy.

These facts make the reports from the Boao Forum for Asia held on April 18–21 all the more surprising. The 20th anniversary economic forum became the biggest in-person conference since the pandemic broke out. Official reports suggest that over 4,000 people from more than 60 states and over 160 organizations from 18 states and regions registered for in-person attendance.

The Forum’s sidelines offer an excellent perspective on a world where Asia is reviving after the pandemic. In global terms, the GDP by PPP share of Asian states amounts to 47.3%, having grown by 0.9 per cent as compared to 2019. In 2020, Asian states demonstrated a 1.3 per cent rise, which is 3 per cent higher than the global average. FDI demonstrated a far more significant difference: while it totaled $476 bn in Asia, with a mere 4% drop, the global average saw a drop of 42%. The Forum emphasized Asia’s role in regional integration (in particular, the RCEP), while the Belt and Road Initiative received its traditional share of attention.

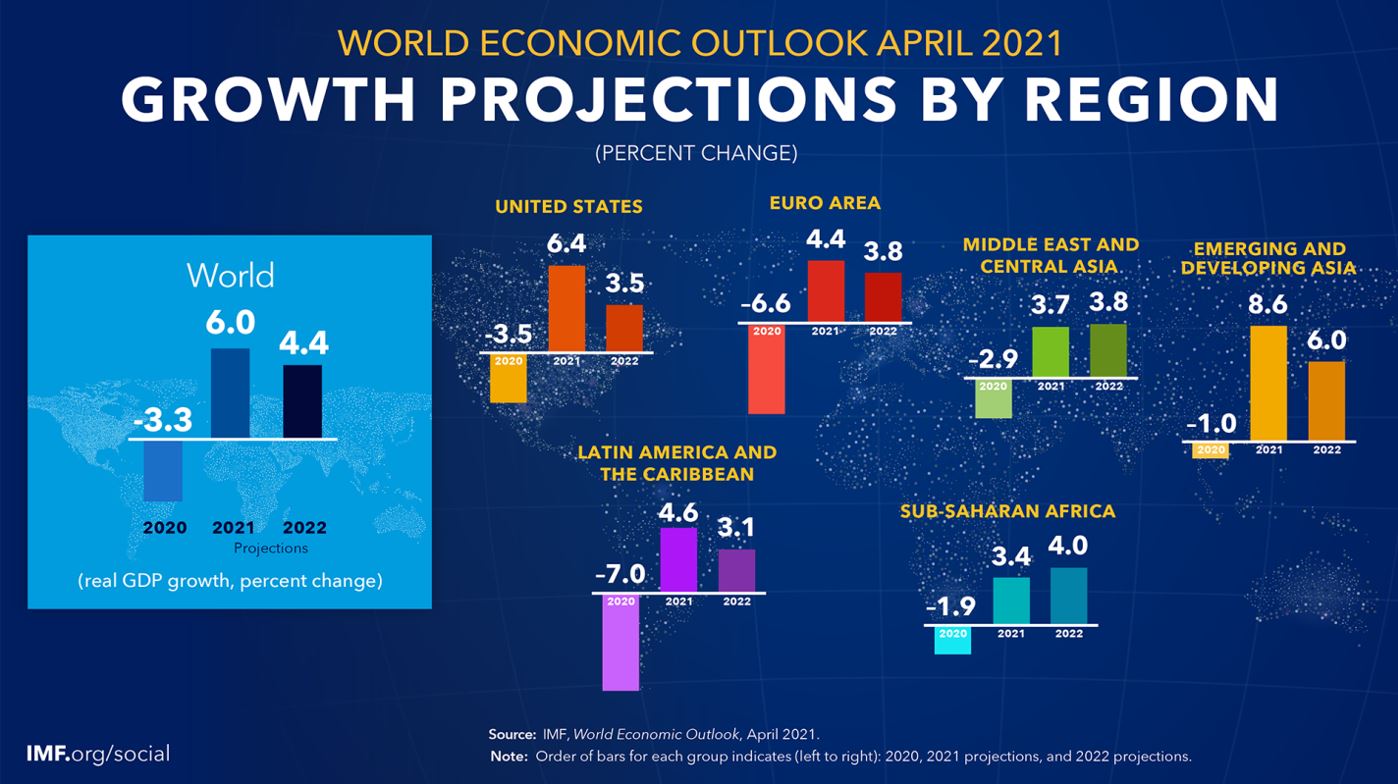

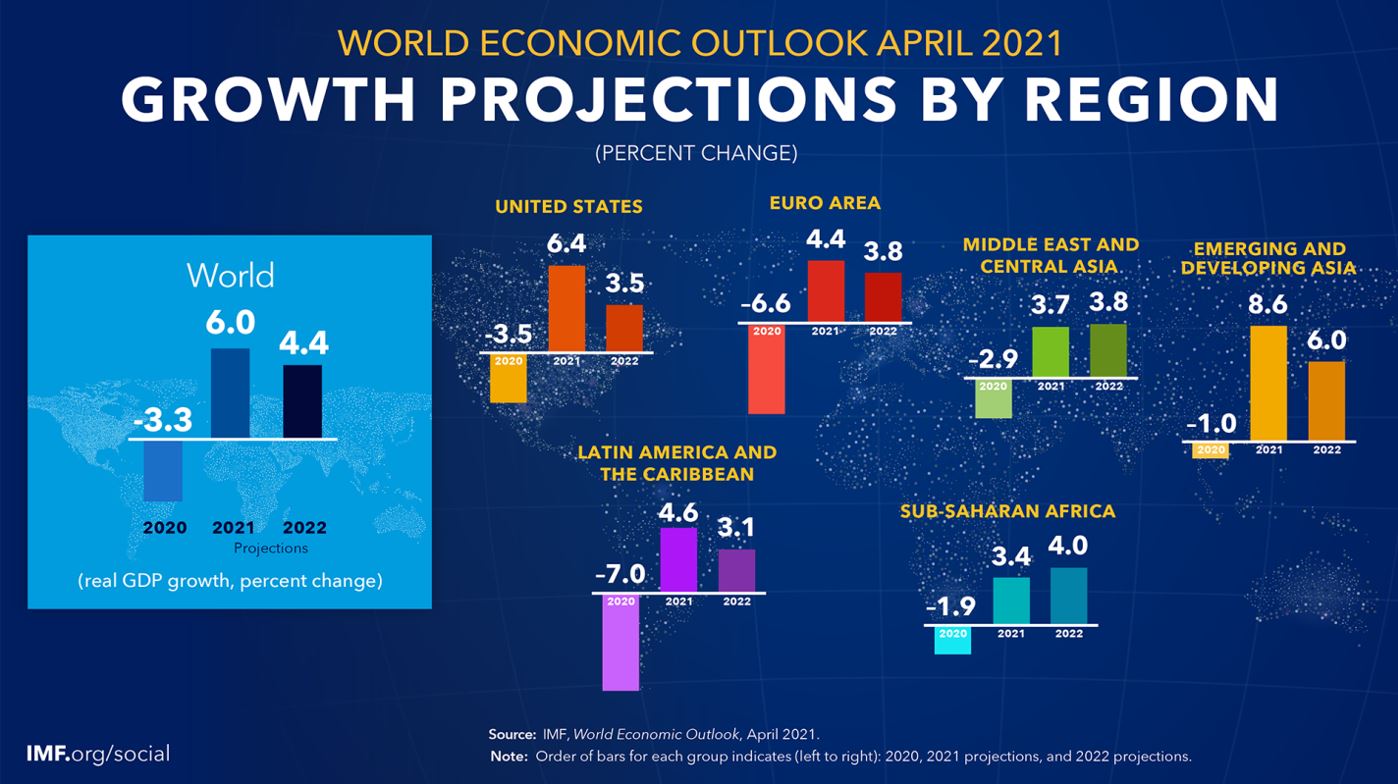

Other sources also report favorable trends. According to VEB reports, ASEAN nations are still China’s main trading partners. In the first quarter of 2021, trade with ASEAN totaled $191.4 bn (a growth of about 35.3%), with Vietnam accounting for the bulk of that amount. The IMF expects Asia to showcase the highest economy recovery rate (adjusted for last year’s low base and the overall level of economic development).

Source: IMF.org/social

Elevated rhetoric is typical of such formats and is certainly not something unprecedented. Yet, the fact that the biggest in-person forum since the pandemic broke out was held in Asia is noteworthy. This once again underscores that Asian states coped best with the coronavirus pandemic, both in terms of countering COVID-19 and relieving its socioeconomic consequences. Nonetheless, such positive rhetoric—coupled with other aggressive phenomena of the international environment—shows that not only has the common misfortune fail to rally the post-COVID world under a single banner but has, on the contrary, served to fragment it further: the world is now highly polarized and extremely heterogeneous.

Features of China’s post-COVID economic diplomacy

Given China’s much more successful recovery after the pandemic, new avenues lie before it. For instance, China became the EU’s biggest economic partner last year, overtaking the U.S. The number of freight trains travelling between the EU and China topped 12,400 last year, which is 50% more than in 2019 and seven times more than in 2016.

China achieved marked results in its cooperation with Latin American and African nations. In 2005–2020, China’s investment and construction contracts in Latin America totaled some $183 bn. Over the same period, China invested about $303 bn in Sub-Saharan Africa, with another $197 bn in the MENA nations.

At the same, we should remember that China’s successes and bright prospects come packaged with a number of long-standing, yet unresolved issues as well as new challenges. For instance, as of June 2020, the debt owed to China by several African states was reported to be over 25% of their total foreign debt (Angola, the Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Cameroon, Ethiopia and Zambia are on such a list). At the same time, China has improved the capabilities of its military base in Djibouti, now capable of receiving aircraft carriers. Such results are directly connected with China’s increased economic presence on the continent.

The same features are largely typical of Asian nations. Huge debates surround the policies pursued by Rodrigo Duterte, who is frequently criticized for his concessions to China (often in exchange for promised investment). Recently, the president of the Philippines was harshly criticized for giving China control over fishing areas in the South China Sea. His policy towards China is contrasted with that of Indonesia’s leader Joko Widodo and his more prudent balancing between the U.S. and China without “kowtowing.” [1] Indonesia was thus able to come to more favorable cooperation terms (for instance, the country received vaccines from China).

Chinese workforce and technologies remain a separate issue when it comes to implementing joint projects. Environmental standards and co-related issues often come up. For instance, protests against China’s growing presence in Central Asian states are not infrequent: over the last two years, there were at least 40 such protests.

Besides, port-related scandals frequently erupt in connection with China, evoking discussion particularly with respect to Pakistan and Myanmar. Certainly, the hottest topic here is Hambantota port that Sri Lanka leases to China. There are regular talks of Sri Lanka being in the “debt trap,” while the country’s officials deny this, claiming that the country will “never be an unsinkable aircraft carrier posing a threat to anyone else.” Additionally, the “debt trap” is often interpreted as part of a more systemic crisis: in Sri Lanka’s case, its causes include the “twin deficits”—trade deficit and budget deficit.

China’s approach to India is a special case in point. Back in the summer, when the border conflict broke out, China responded in a rather restrained manner to the sanctions imposed on it. During the current coronavirus wave rampant in India, Beijing has officially voiced support for New Delhi and offered its vaccines supplies. Nonetheless, the recent incident of a Chinese diplomat comparing China’s outer space successes and India’s funeral pyres has prompted a violent reaction. Although this post has been deleted, the incident produced a powerful impression. This is far from the first instance of China being accused ofusing the pandemic to bolster its global leadership.

The ambivalence of China’s stance is also visible in international institutions. On the one hand, China has greatly benefited from the liberal global order; on the other hand, China regularly stresses the privileges spawned by this order for the West and the injustices when it comes to the Global South.

In spite of this, China remains part of various international regimes, both as the donor and the recipient of benefits. Information surfaced in March of BRICS’s New Development Bank giving China a loan of $1 bn for economic recovery. The RCEP is expected to assist China in implementing the “Made in China 2025” strategy and ensure access for Chinese companies to building supply chains. Additionally, at every multilateral venue, China stresses the need for joint action in combating the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby boosting its international image (in particular, Xi Jinping spoke about this at the G20 Summit in November 2020).

Economic and financial institutions with Chinese participation continue to expand. The review of the AIIB’s five years of operation presented in July last year suggests that the number of founding members has nearly doubled from 2016 to 2020, from 57 to 103; 87 projects were supported in this period and $19.6 bn invested.

From the standpoint of political discourse, we notice a major difference in China’s conduct at international venues and in its bilateral dialogues. Nonetheless, this has had little influence on Beijing’s policies in international bodies, which remain fairly pragmatic. Currently, China is the UN’s second-biggest sponsor following the U.S. and ittakes advantage of UN institutions to promote the Belt and Road Initiative. As of last April, 15 Chinese nationals headed various UN bodies.

At the same time, we have to acknowledge that Chinese initiatives have been put to a major test during the pandemic. In last June, Wang Xiaolong, head of the International Economic Department at China’s Foreign Affairs Ministry, said that the pandemic had seriously affected 20 per cent of the Belt and Road Initiative projects and had a negative impact on another 30 to 40 per cent. Even though the Belt and Road Initiative is still actively promoted, the pandemic will most likely make its own adjustments to China’s investment projects. In particular, forecasts suggest falling investment in extractable resources and some infrastructure projects; greater attention may be focused on projects with a short payback period.

Wolves at our door?

Given the growing external pressure, claims of Chinese expansion and threat persist with varying intensity around the world. Beijing seeks to neutralize them, largely by replacing one idea with another. Yet the practice of combating concepts with other concepts (for instance, replacing “peaceful rise” with “peaceful development,” the “Chinese dream,” the “community of common destiny,” etc.) has apparently not produced the desired result so far.

This is the background that particularly focuses on the new style of the Chinese diplomatic language, which is getting progressively ruder. China’s foreign policy is often termed “wolf warrior diplomacy,” and its practices are expected to become increasingly aggressive. Media have noted that Chinese diplomats went to the trouble of “digging through a dictionary of French swear words” before calling the head of a French foundation a “petty canaille.”

In the heat of playing ping-pong, it is easy to forget it is just a game. It seems like a real battle as it plays out, and the victory appears crucial. When one concentrates on playing, it is hard to reflect and ponder awkward questions. Do we lose important long-term benefits in such a game? Is it really impossible not to play or to choose a different game even if a partner challenges you?

Not to excuse such conduct, but just by way of an observation, it would be fair to say that such a “stylistic simplification” has, in fact, become part and parcel not only of China’s diplomatic language: the same trend can be found in Russian and American official statements (more about this can be found here).

Additionally, it often turns out that inappropriate statements are individual initiatives rather than malicious intents sanctioned by the Communist regime. Excuses for using harsh rhetoric can be found in China’s domestic political demand prompted by China’s growing nationalism and the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to legitimize its authority.

Today, China is still trying out its new global status: it continues to promote the value of international cooperation at various international venues, introduce regional trade agreements, set up new global value chains amid the new circumstances. The devices used to work with countries as part of the Belt and Road initiative and other Chinese formats for cooperation are pragmatically the same, just as before. Moreover, China is not original even in manifestations of its most extreme policy actions: a similar response to sanctions and boycotts was seen in various periods of its modern (and not only modern) history.

Yet, quantity is often known to transform into quality, and this applies to China in particular. We should not underestimate the current transformations. In 2017, for instance, analysts noted that China’s flagship concept of a “community of common destiny” was for the first time officially included in a UN resolution. During the pandemic, the Belt and Road Initiative took on a new dimension as it was augmented with the notion of a “Health Silk Road.” Besides, it is no secret that a cumulative effect often results in common political practices being institutionalized—China’s Ministry of Commerce officially included sanctions into its scope of activities in September, 2020.

The “warrior wolf” diplomacy often looks like overreaction (the events and China’s response are incomparable in significance), and it hurts economic interests more often than not. Summing up, we can say that China’s strategy as a grand concept has long taken shape and is consistently implemented, although quite emotionally. China thinks in categories that entail mandatory accounting for national (domestic) interests. Most likely, China will continue this policy adjusted for the consequences of the pandemic and for episodes of irrational behavior by international actors. Experience shows that one can and should negotiate with China, no matter how harsh the talks might seem. What ultimately matters in ping-pong is not just reaction time and unpredictability, but also nerves of steel.

1. “Kowtowing” is the traditional Chinese ritual of genuflecting before the emperor. Figuratively, it is sometimes used to refer to “vassal” relations between China and its economic partners, similar to the “tribute system” of ancient China.