Civil Society in Ukraine

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Sociology of Political Processes, Faculty of Sociology, MSU

Coordinator at the Reanimation Package of Reforms initiative, Ukraine

The development of civil society in Ukraine has faced many obstacles and is once again at the epicenter of contemporary discussions on freedom, equality, liberalization and respect for law. The ongoing conflict in the Eastern territories is another crucial challenge for civil society, which has yet to find its role in the peacemaking process and offer new approaches.

Building Peace, Democracy and Regional Stability

A thorny road to democracy

Ukraine has entered a new stage in its long and so far uncompleted democratization process, searching once again for a balanced model of governance and a strong basis on which to carry out the many, much-needed political, economic and civil reforms. Ukraine’s road to its model of democracy, as seen in many former Soviet states, is proving to be a non-linear process involving different development vectors. Although the successful promotion of democracy depends on the type of political system and political culture, its driving force has always been civil society, which is a cornerstone of democracy-building itself. The development of civil society in Ukraine has faced many obstacles and is once again at the epicenter of contemporary discussions on freedom, equality, liberalization and respect for law. The ongoing conflict in the Eastern territories is another crucial challenge for civil society, which has yet to find its role in the peacemaking process and offer new approaches.

Even though it may seem difficult to avoid the clichés used in the relentless information wars, understanding the current processes requires concentration not on the clash between Russia, Ukraine and the West, but on Ukrainian civil society and democratization. In the end, it is in the international community’s common interests to see a democratic and stable Ukraine, which needs to choose the right direction and avoid an unwanted return to centralization. In the context of this revival and development of Ukrainian civil society, it is particularly important to consider it not just as a crucial social actor that is predisposed to spread democratic culture, but also as an element within the global democratic network. It is impossible to imagine civil society groups acting independently, therefore discussion on democratic transition, on its complexity and hidden dangers, must not be limited to the government level.

Throughout 2014, Ukraine underwent significant social, political, and symbolic changes, which may create the premises for successful reforms and lay the foundations for the country’s further development. There is evidence that these changes are leading to many positive outcomes. The events on Maidan, mass movement of volunteers wishing to struggle for the country’s stability and sovereignty show that we are witnessing the emergence of a new civil society. Political institutions also underwent profound renewal, producing a dominant pro-European majority represented by the ruling parliamentary parties, the president and the government. They created legal prerequisites for the process the staff renewal within political structures, including within the judicial branch. The country has received powerful political and financial support from international organizations, associations and leading countries of the world, which has led to a gradual change of Ukraine’s image in the world.

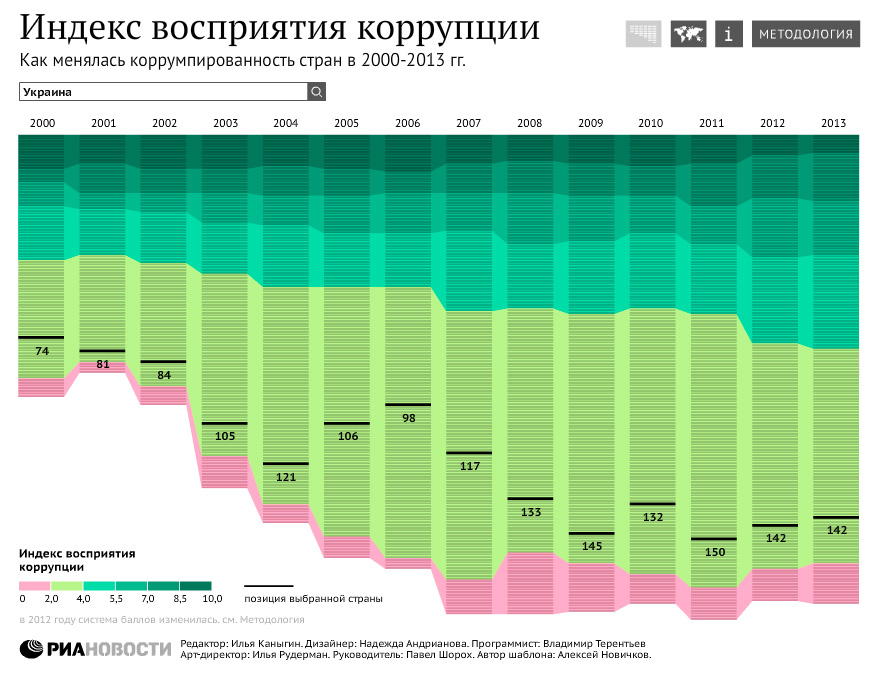

Corruption Perceptions Index - Ukraine

However, the extent of the problems faced by the state has reduced the efficiency of government actions and has sometimes given rise to erroneous political decisions. Among them are the ongoing military conflict in the East, deep-rooted corrupt schemes and practices in the government, lack of qualified personnel in the new government who are able to operate in line with new business and ethical standards, and a desire for rapid change and reforms that are supported by a thorough analysis of the various different possibilities and resources. All this has raised multiple questions – how to avoid the extremes and unwanted deviations in political development and how can civil society contribute.

The roots

The key to understanding the nature of civil society in Ukraine lies in its historical, institutional and cultural aspects. Fifteen years ago an U.S. diplomat Earl Anthony Wayne said that, considering Ukraine’s natural resources, rich agricultural traditions, well educated population and strategic position in Europe, it was predisposed to become one of the most successful former Soviet republics. However, many obvious obstacles were underestimated: the high level of corruption and cronyism, the dominant shadow economy and weak foreign investment, the chaotic political process and bureaucratic inefficiency, all of which have put down strong roots in the new polity. It is impossible to identify just one reason for these problems: most were inherited from the late Soviet era when many of the existing personal ties and rival groups were formed.

On the one hand, the collapse of the regime under the presidency of Viktor Yanukovich came about under heavy pressure from active civil groups, on the other – it was also a total failure of state governance due to their absolute inability to find balance and make an unhesitating, if belated, step towards reforms.

That said, Ukraine and Russia have many common features in their democratization and liberalization experiences: despite the experimentation with different democratic ideas and methods in the early 1990s’, both nevertheless quickly reverted to centralization (under the late Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma in Ukraine and Boris Yeltsin after 1996 in Russia). Weak civil institutions, limited opportunities for successful entrepreneurship and unregulated business relations, which favored privileged minority groups, were stratifying population and delegitimizing the very idea of democratic rule.

However, the hardest issue that accompanied all the post-Soviet transitions has been the emerging split between two different political cultures: one comprising the old rules, behavioral standards and norms; and the other comprising European or Westernized views, understood in various different ways, but all of which are opposed to the previous era. The rising gap between these cognitive matrixes can be explained by the rapid destruction of the old institutions – a process that sowed the seeds of discontentment and misunderstanding among many social groups, including top policy makers, especially those who were socialized during the Soviet period. Hence, a complicated regulating mechanism conducted by the ruling elite was developed, which meant to integrate and reconcile these cultures. Adopted in Ukraine, this versatile system was consistently corroded by imperfect legislation, malfunctioning socio-political representation, unresponsive political feedback and wild capitalism. Moreover, de facto dualistic political culture only just managed to turn into multilateral political competition, and when it did, it ended with cabinet crises. Logically, social actors representing the second political culture lacked sufficient support from the government but were politically active and became more persistent in achieving their goals and defending their rights.

Since the first wave of mass protests under Leonid Kuchma in the early 2000s, which gradually led to the Orange revolution, experts started to talk about the birth of a real civil society that could possibly put an end to the domination of passive political behavior, and help to spread civic culture among the people. However, the inherited political traditions and clientelism proved stronger than innovative democratic initiatives, while civil society still lacked dynamism – the overwhelming majority of the population was either not aware of the new ideas and possibilities or remained inactive due to the rising absenteeism among the young and middle aged people. In 2006, two years after the Orange revolution, three-quarters of Ukrainians said that only those with money and power were equal before the law. At the same time, almost everyone agreed that NGOs should have more freedom in monitoring the electoral process, which was a clear sign of peoples’ distrust in fair elections, despite the new government’s initial willingness to reform the electoral system.

Based on the above and considering the complex nature of Ukrainian society, its ethnic, social, linguistic, religious and value diversity, the relationships between the government and different social actors (business, NGOs, ethno-linguistic groups etc.) can be described as a perpetual search for compromise. From one electoral cycle to another, politicians have been desperately looking for the right balance between the many (openly or latently) conflicting groups, but at the same time they often obviously sided with one party. This biased strategy encouraged the formation of ‘iron triangles’ between big business and (often corrupt) politicians in the executive and legislative branches and did little to support wider social stratums. On the one hand, the collapse of the regime under the presidency of Viktor Yanukovich came about under heavy pressure from active civil groups, on the other – it was also a total failure of state governance due to their absolute inability to find balance and make an unhesitating, if belated, step towards reforms.

A new stage of cooperation between government and civil society

After the regime change in 2014 Ukraine witnessed a new wave of political activity and the rise of self-organized groups and movements that are attempting to articulate different values and create associations that seek to advance different social interests. The younger generations, who were socialized in the post-Soviet era and represent the core of contemporary civil society, are considered as carriers of different cultural and behavioral archetypes and have the potential to generate the long awaited democratic u-turn. Today, after the second wave of democratic mobilization, familiar questions again arise: is civil society finally capable of influencing the policy-making process in Ukraine, break corruption and exert control over ineffective regional and municipal authorities? Are the government and big business willing to support this kind of civil society, both politically and materially? How actively does the new government consult Ukrainian civil society on reforms, especially on constitutional ones?

Ukraine has now over 30,000 registered NGOs and CSOs with the most influential ones in the major regional cities and centers. After Maidan, volunteer movements were generally oriented towards the reform processes, humanitarian issues, providing assistance to IDPs (internally displaced persons) and support for the Ukrainian army. These civil activists see their main goal as initiating the development and reform processes that were not launched by the government. Civil society intends to share and complement the government’s functions in its areas of responsibility.

After the spread of civil actions, presidential and parliamentary elections and the renewal of representative bodies, cooperation between civil society and the government is entering a new phase in Ukraine. A brief overview of the main political structures demonstrates the will to integrate civil society into the policy-making process.

1. Parliament (Verkhovna Rada) and Civil Society

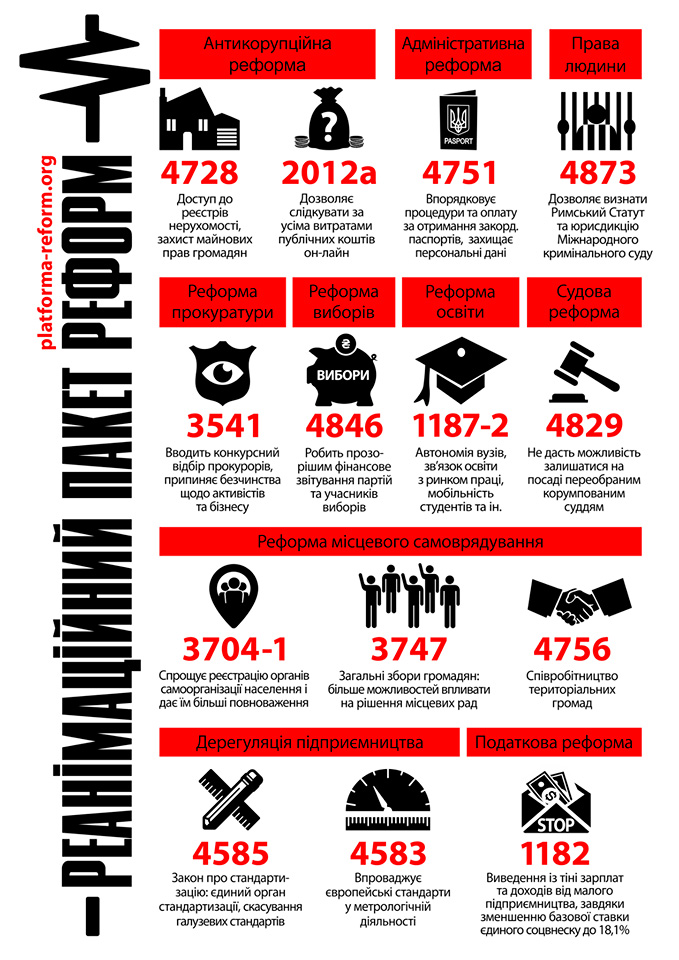

Civil organizations in Ukraine created the Reanimation Package of Reforms (RPR) - a civil society platform uniting influential NGOs and experts across Ukraine that coordinates the development and realization of the country’s key reforms. RPR participants see their mission as uniting the efforts for reforms to build an independent, strong, democratic state where there is respect for the law, a high level of prosperity and equal opportunities for all citizens to develop and self-actualize. RPR brought together more than 300 experts, activists, journalists, scientists and human rights advocates from more than 70 of the most well-known Ukrainian analytical centers and civil society organizations. The participants jointly develop draft laws, lobby for their adoption and monitor the reforms’ implementation.

Civil society’s influence is in its human capital and analytical capabilities. The purpose is to identify positive thinking for the peacemaking process and regional stability and integrate it into the policymaking process.

RPR initiative participants have developed the “Roadmap of Reforms for the Parliament of VIII Convocation” – a document containing systematic and gradual implementation plans in 18 of the most important fields, with each step supported by a separate draft law. On the eve of the elections, eight political forces have signed the Memorandum to support

the Roadmap of Reforms in the new Parliament: All-Ukrainian Union “Batkivshchyna”, “Petro Poroshenko Bloc”, “People’s Front”, “Samopomich”, “Oleh Lyashko’s Radical Party”, as well as the All-Ukrainian Association “Svoboda”, “Civil Position” and “Power of the People”. Five of these have created a Coalition in the New Parliament, and RPR experts participated in drafting the Coalition agreement (most of RPR suggestions were accepted). Later this Road Map became part of the Government action plan.

During one year of RPR’s activity, parliament approved thirty laws, which were further developed, improved, and advocated by activists involved in the initiative. RPR activists cooperate with around sixty reform-oriented MPs and three inter-faction parliamentary groups (Euro-optimists, Deputy Control, Maidan Self-Defense). MPs take an active part in implementing civil society initiatives and involve experts in the preparation of draft laws. Cooperation between parliament and civil society has taken on a higher level of openness and involvement.

2. Presidential Administration

A National Council of Reforms was created to facilitate the implementation of reforms in Ukraine. The Presidential Administration initiated the process and ensured that the National Council of Reforms unites the President, the Cabinet of Ministers, the Parliament and NGO representatives. The Council’s task is to monitor the fulfillment of priority reforms and adopt collegiate decisions on the most important socio-economic issues facing the country.

The Chairman of the National Council of Reforms in Ukraine is the President of Ukraine. The Council consists of the Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (upon consent), the Prime Minister of Ukraine and other Ministers (in agreement with the Prime Minister), the Head of the National Bank of Ukraine, heads of the committees of the Verkhovna Rada, four representatives of civic associations and the representative of the Advisory Council of Reforms (upon consent). Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration of Ukraine Dmytro Shymkiv (ex- CEO of Microsoft Ukraine) has been appointed Director of the Executive Committee of Reforms. An RPR representative is a member of the National Council of Reforms, and systematic cooperation with the Presidential Administration has been established.

A number of laws have been developed by civil society representatives, who helped lobby for them with the Presidential Administration - such the historic package of Anticorruption laws that were put before the Parliament by the President and supported by a vast majority of the Rada.

3. Cabinet of Ministers in Ukraine and civil society

Together with government officials, RPR activists created the Reform Support Center.

The following positive traits should be noted:

- A much higher level of engagement of independent experts in the policy-making process (particularly in the execution of government programs and coalition agreements);

- Active collaboration with civil society organizations fighting corruption and monitoring government actions;

- Engagement of civil society activists in the consulting process for high officials and for executive work in government bodies;

- Much higher, compared to the previous government, level of openness to the general public and mass media;

- Readiness to adopt and implement other countries’ experience in the implementation of reforms and the invitation of top foreign specialists to work in Ukraine’s government structures.

Inter-societal dialogue

Just as democratic rule within a country must encourage citizens to participate openly in the domestic political process, internationally it must encourage them to participate in the global political system. There are multiple mechanisms of non-governmental cooperation for economic, cultural and academic development, the maintenance of international peace and security – from Charter of the United Nation to various regional interactions. Although the Association Agreement implies EU-Ukraine dialogue between civil societies (art. 444), bilateral and multilateral dialogues with other regions and countries must not be underestimated. Therefore, an open and transparent system of national and international non-governmental dialogues with as many interested parties as possible is crucial for Ukraine as the conflict in the East has detracted attention and resources away from fostering cooperation and supporting democratization.

To avoid alienating its own people, Ukraine needs to reinvent the inner regional balance and propose new approaches to integrating the country’s Eastern regions back into the state.

What this dialogue should facilitate is the spread of democratic initiatives at the grassroots level. There are reasons to think that Ukraine’s nascent civil society is a long way from representing the general population whose consciousness is full of destructive labels and whose potential for participation is limited by their disorientation in a rapidly changing environment. It is a promising and dangerous time for the young shoots of civil society, because it depends on its multiplicity. What we call a national dialogue actually consists of numerous grassroots actions concerning corruption, legal loopholes, unemployment, inflation etc. Examples of these horizontal ties that have started to work despite the many political and ideological differences, can be found in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv. This social energy is of a great importance but it has to be structured wisely; it must rely on an effective institutional basis and legal framework in order to become a fully constructive force. To avoid alienating its own people, Ukraine needs to reinvent the inner regional balance and propose new approaches to integrating the country’s Eastern regions back into the state. Realizing these goals, especially in the conflict areas of Donetsk and Luhansk, requires a joint analysis of the situation and consultation involving Ukrainian, Western and Russian representatives from the expert community, the academic community, and business.

The global community has already shown its support for Ukraine in its search for a new model of balanced society, integrity, sovereignty, political and economic stability. European countries, the U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, other countries and international organizations (UN, EU, OSCE, PACE, NATO) are working with Ukraine on a number of issues:

- Supporting reform;

- Building sustainable democracy and promoting respect for democratic principles, the rule of law and effective governance, human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the rights of national and linguistic minorities;

- Strengthening the stability, independence and effectiveness of institutions guaranteeing democracy and the rule of law;

- Ensuring the independence of the judiciary, and the effectiveness of the courts, the prosecution and the law enforcement agencies;

- Conflict prevention and crisis management; cooperative efforts to make multilateral institutions and conventions more effective, to reinforce global governance, strengthen coordination in responding to security threats, and addressing development related issues;

- Assistance in resolving IDP problems resulting from the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. The UN refugee agency reported that fighting in eastern Ukraine's Donetsk region is creating newly displaced people and pushing the number of registered IDPs up to one million. Ukraine's Ministry of Social Policy puts the number of registered IDPs countrywide at 980,000 – a figure that is expected to rise as more IDPs are registered. In addition, some 600,000 Ukrainians have sought asylum or other forms of legal stay since February 2014 in neighboring countries, particularly in Russia, but also in Belarus, Moldova, Poland, Hungary and Romania;

- Building the organizational capacities of Ukrainian NGOs and CSOs;

- Strengthening international ties.

What can be described as progress in Ukrainian-Western inter-societal dialogue is seen as a regress in Ukrainian-Russian and Russian-Western cooperation. But despite the woeful state of Russian-Ukrainian relations and the disruption of many political, economic and social bilateral ties, there are no reasons to believe that these actions benefit either side. Any further worsening would likely trigger more instability, a new wave of trade and gas wars, and the tightening of sanctions towards Russia, but this is hardly going to help find a way out of the crisis. Propaganda machines on all sides have defined the enemies for public opinion. This has affected not only mass consciousness, but also politicians, think thank experts, journalists and civil activists, making it more difficult to distinguish cliché from real analysis and objective perspective. Even if there are potentially influential groups on each side that can at least partly reconsider the existing logical and behavioral dead-ends, they are veiled in total mistrust. This calls into question every analytical data produced by the “rival” side, creating more burnt bridges.

What can be described as progress in Ukrainian-Western inter-societal dialogue is seen as a regress in Ukrainian-Russian and Russian-Western cooperation.

To promote a culture of inter-societal dialogue multiple communication channels have to be put in place. This dialogue should not be narrowed to conflict issues (despite their immense importance). It is vital to create a broad agenda that deals with the root causes of the gap and proposes solutions for long-term stability.

Accordingly, we should talk about different levels of inter-societal cooperation that could and should deal with different sets of issues – in both short-term and long-term perspectives. Long-term issues concern Euro-Atlantic security, stable trade relations and democracy-building in the region. Short-term issues concern conflict-management in the Eastern Ukraine, Ukrainian territorial integrity and economic stabilization. The Ukrainian crisis and atmosphere of distrust between Russia and the West showed that Europe’s security architecture is dysfunctional and has to be partially revised. Government efforts and official diplomatic channels seem unable to overcome the existing gaps, and therefore the involvement of think tanks and NGOs experts from all sides is crucial. There are already different tracks of dialogue powered by such organizations as the Euro-Atlantic Security Initiative, Carnegie Endowment, Nuclear Threat Initiative, Russian International Affairs Council, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Munich Security Conference, European Leadership Network, EU-Russia Civil Society Forum, the recently created EU-Ukraine Civil Society Platform, German-Russian Forum, German-Ukrainian Forum etc. But these ties should not be limited to inter-organizational dialogue, they ought to involve more participants. This discussion implies the involvement of experts, representatives of business associations and academic structures from EU member-states, Russia, Ukraine, United States, Georgia, Moldova, Kazakhstan and other countries interested in long-term regional stability.

Managing Differences on European Security in 2015

The intellectual potential of universities and scientific centers must not be overlooked. There are already numerous conferences and roundtables in almost all major European, Russian and Ukrainian universities and academic centers almost every week, but their coherence and collective impact on policy makers remains low. Other important actors are business associations which represent not only big business and leading companies but also small and medium businesses, thus covering large social groups. A social analysis of the politically active citizens shows that many work in SMEs, and integrating them into this burgeoning inter-societal dialogue would be highly desirable. Regional economic concerns must be taken into wider consideration – how can the EU, Russia and former Soviet republics coexist under the new economic conditions and plan their trade relations? The economic raison d'être could also stimulate the recovery and establishment of the half-forgotten common European home initiatives.

Finally, we should not forget about the core issue – democracy-building itself. Without a broad understanding of the key issues, such as the rule of law, civic culture and participation, multinational and multiethnic coexistence, and institutional balance, no long-term peace can be guaranteed. Such values-oriented dialogue must counterbalance the realpolitik aspirations of experts and decision-makers who propose a new kind of Vienna Congress or Yalta Conference with their “divide and rule” spirit.

The final and essential goal is to transform all these dialogues into a series of coordinated collective actions that could supplement and improve the narrow inter-elite dialogue. Current attempts have fallen short because they lack the involvement of a critical mass of experts, analysts, businesspersons, and mass-media. The results of inter-societal communication should be institutionalized in significant forums alternately held in different cities, primarily in the post-Soviet space. The Munich Security Conference does have a role to play in this dialogue, but does not integrate the needed critical mass. For these events’ objectives to attain their goals, full ideological, political and informational support by local governments and the EU bodies must be provided; they will have to delegate part of their right for negotiations, thus making the whole process more public, legitimate and transparent. Furthermore, without governments’ initial support it would be almost impossible to attain the stated goals. In this context, only politically coordinated, open and transparent dialogue carried out at different levels of society, that includes representatives from all sides who are free to shape an unbiased agenda, can deliver results.

It is time for decision-makers and to understand that future attempts to achieve a sustainable peace will be incomplete without representatives of non-governmental organizations and expert communities.

If transparency and openness become reality, inter-societal dialogue can serve another crucial function – the recruitment of new leaders, more flexible, ready to understand the position of other countries, with new modes of thinking who share common values and who could gradually integrate the cultural environment, which now seems more important than political or economic integration driven by realpolitik interests. Such a coalition of experts, who agree on an agenda, goals and research tools, could deliver universally legitimate and trusted analytical results. It would lead to credible scenario-building regarding economic, integration, conflict, and institutional factors.

However, it does not mean that long-term issues can only be dealt with when short-term ones are solved, otherwise this would be a never-ending process. A stable system of relations can only be constructed through building an atmosphere of mutual trust. If governments generally fail to do so, then it is the turn for inter-societal dialogue to take center stage. If the Ukrainian government is to convince their citizens of its commitment to democratic values and stable development, it must offer a credible model must. But the same can be said about the whole European region, which currently lacks a credible model of stable development and mutually beneficial cooperation.

The impact of Ukrainian civil society institutions strengthened, and there is hope that their quality will continue to improve. This concerns not only participation of independent experts in state policy formation at different levels, but also the pressure civil society institutions exert on the decision-making centers. Competition between civil society institutions representing different ideas and projects on key issues will grow, which can be seen as a positive tendency as long as this competition remains within the democratic framework, and boasts mutual respect and deep understanding of the social, cultural and regional balance. Ukraine today is at the epicenter of complex discussions regarding economic integration, democracy and security in Europe. It is time for decision-makers from all sides to reconsider the democratization processes in the region, to review some flawed strategies and to understand that future attempts to achieve a sustainable peace will be incomplete without representatives of non-governmental organizations and expert communities.

Steps to be taken by civil societies to move forward:

1. Integrate fragmented dialogues between the different sides into coordinated mass events, uniting representatives of the expert community, analytical centers, universities and business. Even one such big conference or forum under the patronage of respected organizations and institutions with well-organized mass media coverage is likely to improve the situation, at least making it more transparent.

2. Think tanks and analytical intuitions from the EU states, Ukraine, Russia, U.S. and other countries must thoroughly coordinate their efforts in monitoring the dialogues within their countries. If there are positive and innovative outcomes, their representatives should be invited to participate in broader discussions. A united think tank or analytical center with good infrastructure could be created to more closely integrate the different sides.

3. Universities and scientific institutions from all sides must be taken seriously because of their ability to create professional discourse on vital issues.

4. Business associations should also become part of the dialogue, especially those representing small and medium business – this will add greater rationality to discussions.

5. Younger generations, who were socialized and professionalized after the Cold War, must be the cornerstone of the dialogues due to their ability to overcome the shadows of the past.

6. It is hugely important to discuss not only realpolitik issues and particular interests, but cultural and value factors. Without this deeper understanding of democracy-building and its interconnection with the still insufficiently studied political and economic cultures of the post-Soviet space, and its social complexity, it will difficult to propose fresh ideas.

7. Possible success in analytical and expert efforts, the involvement of more participants into the dialogue, proposals for innovative solutions could stimulate governments to organize a more extensive inter-governmental dialogue involving civil societies.

8. The goal is to change the perception of the crisis in decision-making centers and to rethink the nature of the dangerous situation in the region. Civil society’s influence is in its human capital and analytical capabilities. The purpose is to identify positive thinking for the peacemaking process and regional stability and integrate it into the policymaking process.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |