Russia and the World: The Agenda for the Next 100 Years

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

PhD in Political Science, Director General of the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC member

Humanity is still aiming towards a future utopia, an ideal world in which the problems of resource requirements have been solved, conflicts have been eliminated, equality among people has been attained and the environment is clean. In an incredibly technologized society, we continue to dream of “paradise”. Today, we are witnessing a clash of two different concepts of “paradise” — the rationalist and the religious. We have reached a stage of human development where progress has ceased to be a universal value and the ideology of the Enlightenment is in crisis. “Paradise” remains excruciatingly out of reach.

For at least the last few hundred years, progress has been a key value and goal of human development. Advances in science, technology, state administration, industry and management have brought unprecedented results. The death rate has fallen significantly and the population has grown many times over. The level of comfort and the availability of various technological benefits is unprecedented. The social structure has become far more sophisticated. The information and biotechnology revolutions have opened up dizzying prospects. All of these achievements would appear to confirm the victory of the ideals of the Enlightenment — the triumph of the rational individual over the forces of nature and social prejudices. What we are seeing is the gradual emancipation of the individual, who has been freed from material and social constraints and given greater opportunity for self-realization.

Of course, there has been a downside to this progress. The achievements of reason have at times intensified the destructiveness of human nature, limited freedom, and brought about great disasters. Resources are distributed very unevenly. The industrialization of war, the new technologies of power and social control, and technological catastrophes have periodically thrown us off course. But each time they also gave rise to new waves of progress. To this day, progress and development remain a key element in the legitimacy of the vast majority of states and all major international organizations.

Generally speaking, humanity is still aiming towards a future utopia, an ideal world in which the problems of resource requirements have been solved, conflicts have been eliminated, equality among people has been attained and the environment is clean. In an incredibly technologized society, we continue to dream of “paradise”. And in this sense, the behaviour and motivation of the technocrat differs very little from the tenets of the key religions. The only difference is that, for the technocrat, achieving this “paradise” is a material task, while for the religious leader it is the result of spiritual work.

The history of the 20th century, particularly the second half of the 20th century, showed that a technological “paradise” is theoretically attainable. A whole host of developed nations that have achieved significant results in terms of development has appeared. Paradoxically, technological progress has given rise to serious doubts among philosophers and intellectuals about the status of the “spirit” in developed societies. Long before the technological accomplishments of today, philosophers such as Nietzsche, Spengler, Danilevsky, and many others expounded upon decadence in society. The reaction of non-Western states has been especially revealing here — while borrowing western technology and management systems almost wholesale, they have attempted to preserve their own cultural autonomy. This reaction has been most clearly pronounced in the Islamic world, with its most destructive manifestation being found in Islamic extremism, invoking as it does religious roots and “first principles”. Islam as a world religion has absolutely nothing to do with the beliefs of radicals purportedly acting in the name of that religion. But the fact that they use religious ideas is itself very telling.

Today, we are witnessing a clash of two different concepts of “paradise” — the rationalist and the religious. And the proponents of the latter actively use the latest technology to promote their ideas. The limits to the growth of the technocratic “paradise” only make them stronger. We have reached a stage of human development where progress has ceased to be a universal value and the ideology of the Enlightenment is in crisis. “Paradise” remains excruciatingly out of reach, which means there is a greater likelihood of major upheavals taking place. Paradoxically, it could also mean “salvation” for a great many societies.

“Salvation” and “paradise” are metaphysical terms. However, using them to understand the situation in the modern world makes perfect sense if we bring to mind the names of at least two scholars, both of whom practiced the natural sciences. And we would do well to invoke their legacy today.

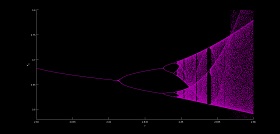

The first is Pierre François Verhulst (1804–1849), a Belgian mathematician who created a number of models in population dynamics. One of his achievements is the concept of resource niche. Every population (including the human population) requires resources in order to grow. As a rule, resources are limited. But these limitations are “soft” — they can be overcome by creating new technologies or by transitioning into different niches. What is more, this is a nonlinear process. The pressure of restrictions is disproportionate to efforts to find new possibilities. As a rule, this search usually comes late. That is, the population continues to live the old way until it becomes impossible to do so. Stepped-up efforts to find new resources yield ever decreasing results, due to the simple fact that they are running out. And this leads to disasters — severe crashes and crises. These crises are intrinsically chaotic. Population dynamics change suddenly and dramatically, and they are impossible to predict. Moving into a new resource niche is a bifurcation point, offering a choice of many alternatives. Survival by expanding the existing niche is just one of the options. Another is the degradation and destruction of the population.

In Verhulst’s vocabulary, “paradise” is a state in which resources are unlimited. This means that there is no need for competition for resources. Population growth and quality of life are also unlimited. When resources are limited, the illusion of “paradise” can lead to a post-crisis transition to a new resource niche, during the initial stages of which there are enough resources to go around and competition for them is low. When resources run out, “paradise” turns into “hell” — fierce competition for dwindling resources. “Salvation” in this case means transitioning into a new resource niche.

Generally speaking, the idea of progress implies that the “end of history” has been achieved — a point at which resources are either unlimited or society is organized so efficiently that the search for new resource possibilities is carried out in good time. This means that crises and disasters will be a thing of the past. It is worth bringing to mind a second scholar here, one who achieved victory for rationality in the post-war years.

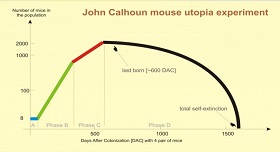

John B. Calhoun (1917–1995) was an American ethologist who became famous for his long-running Universe 25 project. In the experiment, four pairs of healthy rodents were placed in a container that had a continuous supply of food and water, was always heated to a comfortable temperature, and was free of predators, disease and all other kinds of threat. The size of the container and the amount of food, water, living space and other resources were so vast that it could easily accommodate 4000 rodents. A bona fide “mouse paradise” had been created under laboratory conditions. The mice were free to mate without having to worry about the resource niche, which was essentially limitless. This meant that the population should have reached capacity at the very least.

Initially, the mouse population in the container increased exponentially. After a while, however, growth began to slow down. At a certain point paradise collapsed. Outcasts appeared within the colony — young mice that did not fit into the existing hierarchy. The males began to lose interest in mating and competing for the females, who, in turn, became more aggressive, isolating themselves from society and destroying their offspring. Despite the surplus of food, cannibalism began to flourish. A group of “beautiful ones” appeared — males that took great efforts to look after themselves, lived separately from the rest and refused to mate. Having reached a population of 2200, the colony began to shrink, despite the fact that the container could easily have accommodated twice as many mice.

In other words, living in the “paradise” of unlimited resources, the colony initially grew rapidly before experiencing a kind of death of natural instincts, complete social breakdown and eventually physical death. Calhoun’s experiment was widely discussed at the time in relation to the future of humankind and individual civilizations. Specifically, it once again highlighted the problem of the breakdown and demise of civilization that had been described by Arnold J. Toynbee and Pitirim Sorokin.

Verhulst’s models and Calhoun’s experiments (as well as a number of other studies) illustrate the ambiguity of progress — and thus the difficulty of predicting progress — very well. We are talking about both methodological and ethical difficulties here. Methodologically, the obvious difficulty is in the nonlinear nature in which social systems develop. What is more, nonlinearity appears even in cases where all the conditions for linear and unlimited development have been created. This is precisely what happened with the “mouse paradise”. The ethical difficulty lies in the fact that achieving “paradise” does not solve problems. On the contrary, it creates new and far more dangerous problems.

We kept both of these difficulties in mind when launching the “World in 100 Years’ Time” project. This is why we decided to abandon all attempts to imagine a utopia, to build a coherent and non-contradictory picture of the future, the end of history and “paradise”. However, refusing to speculate about the future in many regards robs us of the future. We therefore decided to take a different path and conduct a kind of brainstorming session with representatives of various industries. What we have as a result is a number of different pictures of what the world will look like 100 years from now, imagined by people with different professional experiences. A mosaic of this kind seems to offer greater advantages. It leaves room for intellectual manoeuvre while at the same time giving the reader an idea of how experts in their respective fields envision the future of these fields.

As a result, we received over 50 essays on various issues, including: the future of political borders; demographic dynamics; language development; the future of the mass media; armed conflicts and technology terrorism; the future of the state; global finances; cyberspace; the energy industry; epidemics; the resource deficit; and much more. Each essay provides professional insight of Russian scholars on the future of these fields.

One of the key issues in our work was deciding the period of time that will be subject to prognoses. One hundred years is a long time, perhaps too long to make concrete predictions. Just look at how the world has changed over the past 100 years and how naïve the predictions made back then were about what life would be like now. This is nevertheless the period of time that we chose. There are at least three reasons for this.

First, the speed at which change happens is not uniform. Change can happen rapidly (as we saw in the last century) or at a slower pace. The explosive development of certain technologies may co-exist with conservatism in others. For example, variations on electronic technology appear every few months. In a very short space of time, we went from using bulky PCs to laptops, and then more compact and multifunctional tablets and mobile telephones. At the same time, the Kalashnikov rifle continues to be the weapon of choice in the Russian army after 70 years, and is actively used in over 50 countries. What is more, new and “conservative” technologies often converge. One example of this is the Internet of Things, where the functionality of seemingly ordinary objects — from household appliances to cars — is expanded significantly by being connected to the World Wide Web. Another example is the use of advanced technology to guide relatively old weapons systems. These new navigation systems have significantly increased the effectiveness of bombs that were designed 70 years ago.

Second, many technologies, institutions, and social processes are built to last. For example, the lifecycle of a nuclear aircraft carrier from design to decommissioning is over 50 years. State borders can change overnight and then remain stable for years. Despite today’s dynamism, many social institutions change over the course of decades. And this happens, once again, in a nonlinear fashion. The revolutionary pace of changes in a number of spheres does not mean that that particular revolution will continue for a long time. Revolutions are often followed by periods of stability, the gradual assimilation of new resource niches.

Third, when predicting the near-future, experts tend to rely on extrapolations (everything will be more or less like it is now) rather than making true predictions. Looking 100 years into the future can have similar problems. But it is big enough to go beyond the current situation.

The essays presented here allow us to make a number of suppositions about what the world will look like 100 years from now. Roughly speaking, they can be reduced to the following basic points.

1) In the next 100 years, we can expect to see a crisis in global demographic trends. The past 100 years saw unprecedented growth of the population. This probably will not repeat itself, however. It is more likely that growth will slow down significantly in the next century, or perhaps even begin to shrink. The changing patterns of reproductive behaviour in urban society will contribute to this (although this does not address the issues of development and quality of life).

2) The global population will become more mobile. This will be helped by the possible removal of physical barriers between states, as well as by the level of communications already achieved in today’s world. The universalization of the English language as a means of global communication will give impetus to this internationalization. The population may be forced to become mobile by political upheavals and conflicts.

3) A mobile population and more stable population growth will not solve the issue of there being a shortage of land and resources as a result of the population being distributed unevenly. The fact that the population is concentrated in cities creates a need to develop new ways of organizing urban space.

4) The explosive growth of production and the dissemination of information have apparently not yet reached their limits. The problem now is not that there is a shortage of information. On the contrary, we are overloaded with information and will remain so into the future. As a result, we are seeing information channels becoming congested. And the need for the targeted delivery of information and for adequate means of storing the information that has arisen. The Internet of Things will lead to even greater amounts of information. The possibility of creating a direct link between informational systems and the human brain (by implanting a network into the brain) will lead to the next revolution in the informational sphere. In addition to providing new possibilities, this will raise questions regarding the autonomy of the individual and his or her freedom and protection from the all-encompassing control of the state and corporations.

5) The balance of powers in the world will change. The instability of the world order is fraught with conflicts between the leading players and the reshaping of boundaries. State boundaries will alter in a number of regions. These processes are already under way in the Middle East and Central Europe, and could very well spread to Africa and Central Asia. The boundaries will change as a result of integration processes in individual regions — for a number of successfully integrated groups, they will disappear entirely because they will no longer be necessary. But these borders can be restored just as quickly with the influx of people from crisis regions.

6) At the same time, the revolution in the military sphere will gain pace. Old military technologies will be complimented by a new informational component. A qualitative breakthrough in the management and use of the armed forces is also possible, as is achieving new levels of fluid, remote, and automated modern warfare. Aviation and a number of components of the naval and land forces could change dramatically. This will in turn lead to the advancement of robotics in the army, which will abolish conscription. At the same time, the fact that information technology penetrates all levels of society will mean that the chances of building a “massive” army will remain, but on new technological and managerial principles. IT experts will be able to adapt their skills for use in a military environment. This is precisely what happened with industrial workers 100 years ago, who quickly adapted to the new technologies and techniques of warfare.

7) Competition between states will unfold against the background of growing global problems. One of these problems will be the appearance of new infectious diseases and epidemics, which can only be tackled by developing institutions of global governance. And this, along with other factors, will put issues of state sovereignty, the limits to interference in the internal affairs of a state and the instruments that can be used legitimately in such circumstances on the agenda once again. The contradiction between the need for global governance on the one hand and sovereignty on the other — between building a world order and maintaining global anarchy in international relations — will grow.

8) Competition between state and non-state actors could grow. The state’s key competitors are transnational companies with financial might and access to market information. Companies, however, do not possess instruments of legitimate violence. They will thus have to rely on the state apparatus to protect and promote their global interests. Terrorists of all colours represent another kind of competition for the state. Technological development will make the state infrastructure more vulnerable to both traditional and new forms of terrorist attack. The number of crisis and “fragile” states — a fertile breeding ground for terrorism — will grow. Cyber-terrorism is an untapped niche for radicals. The next 100 years will see individuals and states become increasingly vulnerable in cyberspace.

9) At the same time, the erosion of sovereignty will most likely be uneven in nature. The number of weak states will grow, while a small number of states will grow stronger — stronger both in terms of control over their own populations and in terms of projecting their power to the world. Weak states will remain the arena for competition among the leading powers in the event that their attempts to build effective institutions of global governance are unsuccessful.

10) Radical changes will take place in the energy sector. And these changes will be dictated not so much by a lack of resources as by environmental changes — climatic and environmental shifts. The global energy balance could alter drastically. Solar and wind energy, which is more expensive, may be in demand due to the high costs of dealing with the consequences of climate change.

11) Revolutionary changes are likely to occur in education. Distance education, a dramatic change in the types of profession and a fundamentally new level of accessibility and spread of information will change the nature of university and indeed other educational institutions. Education may become much more individualized, geared to the needs, idiosyncrasies and interests of every single individual. However, paradoxically, specialized education may go hand-in-hand with the degradation of general and fundamental education. At the same time, investment in science will probably outstrip economic growth.

12) Another significant trend is the transformation of political ideologies. The concepts of freedom, authority, equality, legitimacy and other fundamental political categories will be invested with new meanings. This will be happening against the background of a new wave of “panopticism”, i.e. growing control over the individual and a reduction of real freedom, as well as new conditions of the information environment in which it will be extremely difficult to ignore the opinion of the masses. We will probably see growing competition between secular and religious state-building projects.

These are just some of the generalizations that can be derived from the body of expert opinions on various aspects of international relations, technologies and institutions. Clearly, humankind will have a host of diverse problems to deal with. We will probably be spared Calhoun’s “mouse paradise”. This, of course, does not quite secure us against a very human “inferno” should nuclear weapons be deployed unintentionally, or if epidemics or climatic catastrophes hit the planet.

But what will become of Russia? In 2008, we developed a number of predictions (scenarios) with Andrey Melvil of what Russia’s future will look like. The horizon of our scenarios was much shorter, with our projections extending until 2020. However, the scenarios themselves do not matter as much as the driving factors (independent variables) that determine the country’s future. These independent variables go well beyond 2020. The following variables (factors) need to be mentioned above all:

Factor 1. Russia’s ability to build a diversified knowledge economy, attain a high level of technology and added value in a broad spectrum of sectors ranging from agriculture and mineral extraction to processing and engineering. Achieving that result calls for more than just political will. The direction of change in Russian society is very important. New ideas, technologies and added value are generated in an uninhibited social environment with a high mobility potential. An isolated, atomized society consisting of quasi-estates is unlikely to generate innovations on its own. Innovations ordered “from the top” would merely consign Russia to a perpetual role of “catching up”. Favourable prices for raw materials would temporarily mitigate the problem, but would hardly create a solid basis for the future. At the same time, the role of the strong state in supporting a liberated society is fundamental. Without guaranteed law and order, such a society would plunge into anarchy and free-for-all.

Factor 2. The country’s political structure. The state has traditionally played a great role in Russia’s development. All the main social upheavals of the 20th century began with a crisis of the state, the inability of the political system to meet new social demands, the changing economic paradigm and external challenges. Subsequently, it was the state that acted as a driver of the resurgence and mobilization of the nation. Obviously, copying foreign political systems is unacceptable for Russia. Each system arises as an answer to specific national tasks, problems, and contradictions. There is little reason to simplify the alternative of Russia’s political development to the opposition between democracy and autocracy. Even so, the stability of Russia’s political system would depend on the state’s ability to ensure feedback with society through a truly representative system. To ensure the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary. To encourage competition, especially at the local and regional levels. Such conditions are of course fraught with serious political risks. Any reasonable leader will be afraid to lose control of the situation and the country. However, conservation of the system, “manual control”, and total dependence on the leadership institution also involve serious risks, especially in such a vast and complicated country as Russia. The upheavals of 1905, 1917 and 1991 occurred because of the refusal to introduce political reforms in a timely and gradual manner. Apparently, Russian political leaders will long be faced with a choice between concentration of power for the sake of stability, and political reform to avoid still worse consequences. Each time it will be a difficult choice. Each time the country will be confronted with risks of autocracy on the one hand and anarchy on the other. The dilemma is made more complicated still by the rapid changes of modern society, its informatization and growing mobility. The solution calls for wisdom, common sense, trust, and painstaking joint work of the authorities and society.

Factor 3. Territorial structure. Throughout its history, Russia has been a complex society with various cultural, religious and economic orders. The country has lived through painful processes of disintegration twice during the past century. Each tended to increase ethnic nationalism on the periphery. The threat of a break-up of the country is one of the key and legitimate fears both of society and its political elite. One answer to the challenge was federalization of the country in search of a balance between the self-government of the regions and strong federal power. Modern Russia has managed to build a fairly stable system of centralized federalism. However, there is no guarantee that it will remain stable. It is challenged by the shrinking “resource pie” due to price fluctuations. Faced with a resource deficit, one possible strategy is to make the regions more responsible for their own development. But that would mean giving them greater political independence within the Federation, which inevitably increases the risk of the centre losing control. Like in the case of changes to the political system, any transformation of the federal system would present the leadership of the country and the regions with a daunting dilemma. Meanwhile, many regions feel quite comfortable as part of a centralized federation. Whether the choice is made in favour of increasing or decreasing centralization, that parameter is a major long-term factor in the country’s development.

Factor 4. The impact of the external environment. All the aforementioned upheavals of the 20th century were triggered by external factors. The troubled times of 1917 and 1991 unfolded against the background of fierce political competition in the world arena. The very existence of the Russian state and society was threatened from without. While during World War II the direct threat was posed by Nazism, during the Cold War it was the underlying threat of nuclear annihilation. The only reliable way to neutralize that threat for both opposing blocs was to build up their own nuclear deterrent potentials.

The current danger is that after the end of the Cold War a new world order has not been formed. Instead of harmonious transformation, we are likely to face a period of chaotic change. The safeguards that could hold the world power centres back from a military showdown are being thrown out the window. The trouble is that local conflicts may well erupt into large-scale clashes. Given the arsenals of nuclear and other new types of armaments, that is an extremely dangerous scenario.

Much will depend on Russia’s own approach to international relations and its perception of the external world. The country will inevitably be faced with two extremes. The first is the objective need to become integrated into the globalizing world and borrow the best international practices and competences. Russia itself has a lot to give the world. The second is the need for security, for pre-empting possible military and non-military challenges. And there are challenges galore. All the key players find themselves in a similar situation. Their ability to act in concert and avoid confrontation would be critical both for Russia and for the whole world.

At the end of the day, the majority of our contributors agree that the world will become increasingly interconnected, not only in terms of trade, economics, and information, but also in terms of threats. That would force Russia to solve its dilemmas in close connection with global problems.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |