Tea and Cognac: A macroeconomic outlook on Chinese investments in the Black Sea

In May 2017, Beijing and Tbilisi signed a Free Trade Agreement, almost one year after the entry into force of the Association Agreement between the European Union and Georgia. Besides the political success (it took only a couple of years for Beijing to reach the same outcome as the European Union in more than a decade of negotiations), the Chinese decision to launch such an agreement with Tbilisi is therefore probably not a coincidence. Located at the crossroads between Asia, Europe, and the Middle-East, Georgia is China’s gateway to the European and Russian markets, while its Belt and Road Initiative (formerly known as OBOR) aims to connect the continents to increase trade. In this context, and although not constituting official axes of the new silk roads, several projects have been launched, such as the Baku — Tbilisi — Kars railway line, inaugurated on October 30th 2017, and going through Turkmenistan, Iran, Armenia and Georgia.

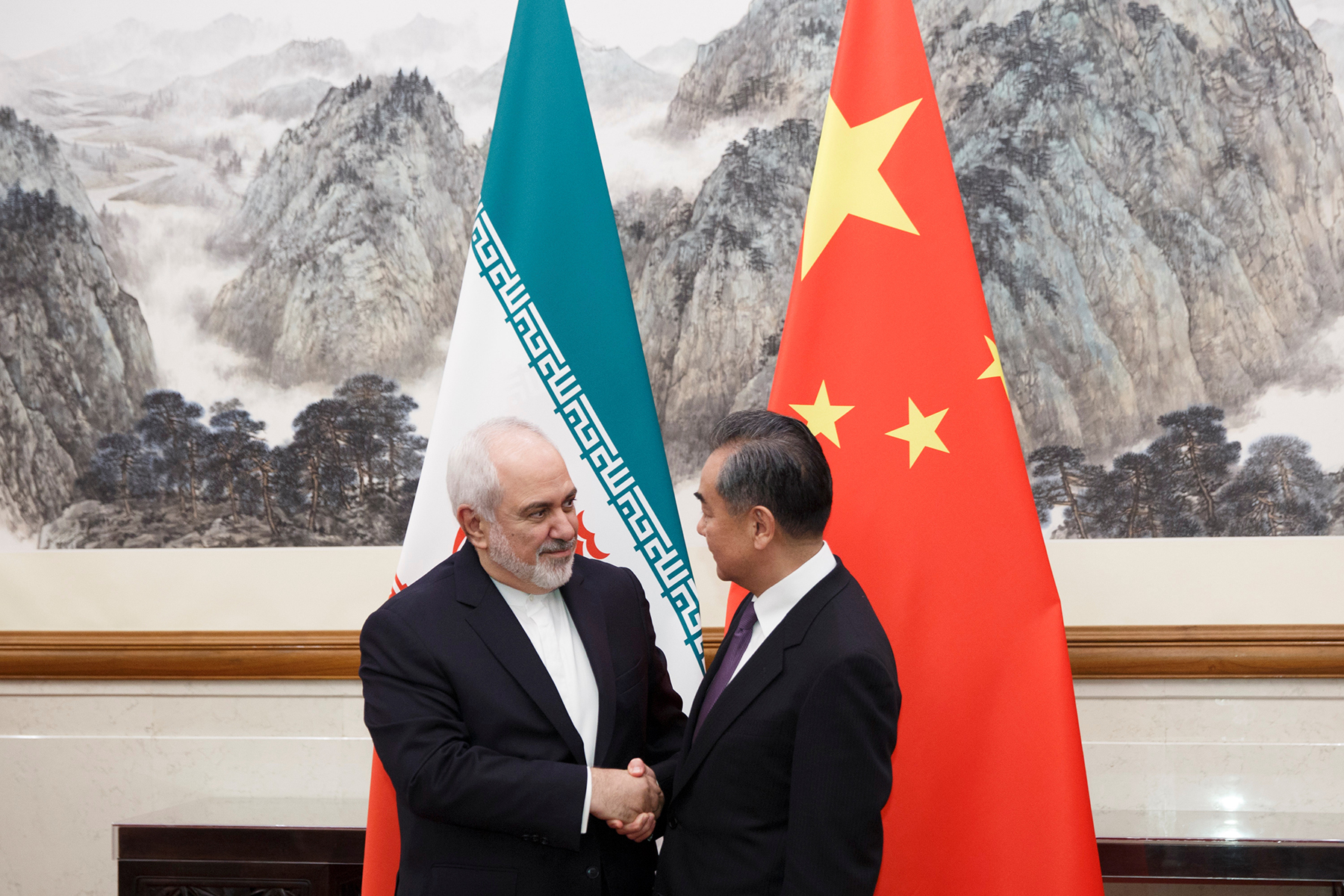

As underlined during the South Caucasus Security Forum 2019 in Tbilisi, Georgia remains committed to NATO and European Union integration while pretty much all neighbor countries have decided to focus on other partners. As a matter of fact, Armenia has become a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, the Islamic Republic of Iran is seeking more investments from China, and Abkhazia and Russia are skeptical regarding NATO and EU interests in the Black Sea region. Despite political speeches from the Georgian leaders, it seems difficult to deny the growing interest for China and the Southern Caucasus.

The Chinese-Georgian Agreement officially entered into force on January 1st, 2018, should facilitate exports in both countries, especially when it comes to wine, mineral water, and agricultural products. Georgian goods are now gradually leaving the Russian and EU market, where they were relatively well known and appreciated, to end up in China. For example, between 2016 and 2017, Georgian wine exports to the Chinese market increased by 43 percent, making China the largest importer of Georgian wine after Russia and Ukraine.

China has become a major player, and the Chinese language is now the third foreign language taught after English and Russian in Georgian universities. The Chinese stalls are multiplying, and the buildings in the Tbilisi Sea Plaza with the international trade center are growing rapidly, making emerge an imposing Chinatown within the capital and gradually erasing the old Soviet buildings from the landscape.

A similar situation is happening in the other states of the Black Sea region, particularly in Ukraine where trade with Beijing increased by 18 percent between 2016 and 2017, and in Moldova which now exports cognac, wine and tomatoes to Chinese territory. Chisinau also negotiated a free trade agreement with Moldova in 2017. In Armenia, China’s presence is also visible on the territory. Surprisingly, public transport buses in Yerevan display a Chinese flag on their facade, which 250 of them have been donated by Beijing to Armenia in 2012.

Overall, Georgia and Ukraine are the two most skeptical countries when it comes to Beijing, probably due to the relationship between Russia and the People’s Republic, and this is leading to a new fragmentation between states who are choosing or at least understanding the interest to focus on China (Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia) and the others who are interested in NATO and the EU since the break-up of the Soviet Union.

Para-states also have an opinion and should not be excluded from the (geo)political debate, with a growing interest from Abkhazia in having more Chinese tourists and investors in honey and wine industry while Transnistria would like to export more cognac in Asian markets.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the West and Russia should keep in mind the whole population in the South Caucasus is no more than an average city in continental China. While the European Union and Russia are struggling with the political and economic crisis, China is having an impressive budget and a strong appetite for all kind of goods.

China and the post-Soviet para-states

While EU member states and the United States of America still dare to invest little in the unrecognized Russian-controlled para-states in the post-Soviet, at the risk of offending relations with countries to whose sovereignty they belong, China, meanwhile, is not limited to the borders recognized by the United Nations. Thus, the Kvint group in Transnistria, a de facto state that declared its independence from Moldova in 1991, could not hide its astonishment when the Chinese delegation visited the territory to increase imports of Transdnistrian cognac.

In Abkhazia, a territory only recognized by Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru and recently Syria, the authorities decided to refuse China’s offer to send 3,000 Chineses workers to invest in the renovation of ports and roads, fearing losing control of the territory and their identity. Despite this, Chinese investments in this territory of only 240,000 inhabitants are real, albeit limited to a few agricultural businesses.

The para-states are for China an opportunity to develop its investments. Indeed, social standards are lower, products easier to tax and wages are more affordable compared to other recognized countries in the region, while the working conditions are not looked at. Beijing seems to be taking a certain advantage from the frozen conflicts and rivalries in the Black Sea region and is counting on an intervention by the Russian army in the event of an attack on its infrastructure. As such, it does not hesitate to play on pre-existing tensions such as those between Armenia and Azerbaijan for the construction of its infrastructure supposed to connect Russia to Turkey and Armenia to Iran.

The Chinese policy regarding para-states is not so surprising when we look at Chinese history. As a matter of fact, the People’s Republic has been a para-state for more than a decade until French diplomatic recognition while only recognized by the Soviet Union for a long time. Moreover, the Chinese territory has been divided between Germany, Great Britain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Japan, just to name a few of the colonial empires.

Beijing has developed specific diplomacy based on soft power and economic influence in Hong-Kong and Macao, improved after the Kosovo war and the partial recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Russia. Beijing is focusing on a new strategy to take back Taiwan without violence. The crisis in Kosovo and the bombing of NATO led to an anti-Western feeling, and China is not ready to help the West in the Black Sea region, while the relationship with Russia is complicated because of the Soviet past (the USSR has been against an autonomous Chinese nuclear deterrence policy).

Looking at the difficult experience of the West in Kosovo, the struggling of Russia to bring more country to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Beijing came rapidly to the conclusion the best way to ensure prosperity is to avoid using both military pressure and diplomatic recognition, staying open to working with all countries — even when they are not or partially recognized — and invest in tourism and farming because, whether some like it or not, para states have resources and products to export abroad.

China is especially interested in land, farming — tomatoes, and honey to be a priority — but also tourism in Abkhazia and possibly peacekeeping operations in relation with the Russian Federation. The Chinese pharmaceutical industry is increasing its presence in all para-states and all combined the targeted population of Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh represents more than 1 million inhabitants with a lack of providers but Russia, Turkey (Abkhazia) and Armenia.

From a military perspective, Georgia seems to be the most interesting, but its focus on NATO and the European Union, is pushing China to be more interested in finding other partners such as Armenia and Azerbaijan, or potentially Abkhazia due to the strategic access to the Black Sea and possibility to secure goods coming from the Middle East to Georgian harbors. However, Chinese involvement in Abkhazia would be done with peacekeepers, and Russia may not agree. Settling in Georgia would be much appreciated with China having access to the sea, Georgia increasing its protection against Russia, and Russia assuming the People’s Army will bring Georgia closer to the East and away from Western institutions.

Besides the military projection, we can’t deny the strong interest of Beijing for Georgia will have an impact on Georgia’ geopolitics because it would be difficult to stand on Western state’s side while relying on Chinese investors. Moreover, Chinese investments in para-states is a way to measure the reaction of the West to see, in fine, the motivations of Great powers to stand on the way for the reunification with Taiwan. The Chinese Government is expecting to get closer to Taiwan around 2025-2030, which is leading to the possibility of Chinese military involvement in the Black Sea and especially para-states in the upcoming decade.

The (lack of) reactions from Moscow and the West

How is Russia reacting to Beijing’s growing power in its near abroad? The relationship between the two countries appears more and more unbalanced, both economically and militarily. China is already the largest importer of Russian goods, which limits Moscow’s ability to disapprove any choices coming from its Chinese neighbor, while the countries in post-Soviet space see the Chinese presence as a way to disengage, step by step, from the Russian influence. Given its economic difficulties, increased by Western sanctions, Russia sees in China an opportunity to strengths its economic power too. The Kremlin hopes to take advantage of the OBOR to develop its infrastructure, particularly in the Siberian region (Beijing has issued the possibility to use the Trans-Siberian for freight transport to Western Europe).

Russia is not in a position to negotiate due to the demographic (144 million vs. 1.4 billion), economic, and military dominance of China. In many aspects, we could even consider the Eurasian Economic Union to be an attempt to avoid a new alliance between China and Central Asian states. The infrastructures are being taken by a Chinese investor in the whole post-Soviet space with the project to renew the harbors in Georgia and Ukraine, new train and roads projects for merchandises in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Increasing on wine export from Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, not to mention the increasing interest to settle Chinese peacekeepers in the Black Sea region to renew with the Chinese success in Djibouti, Africa.

Moscow is optimistic regarding the Chinese investments in the post-Soviet space but also aware it will be leading to issues regarding separatism in the Russian Far-East and more illegal immigration in Russia from illegal settlers interested in starting a business in Russia. The recent visit of the Russian President to China in June 2019 is also showing an increasing friendship between the two powers for more economic cooperation as a consequence of the trade war between the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America.

For their part, the Western countries seem to follow the same path towards China’s growing presence. Washington, trying to contain Beijing in the South China Sea, cannot afford to curb its economic presence in the eastern and western parts simultaneously. The EU countries, for their part, are not in a position to offend their relations with China and appreciate its economic assistance in the Black Sea region since the investments of the Eastern Partnership do not seem to give the results expected. Most EU states are struggling with harsh economic context and immigration of young people — Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece — and are welcoming some help from outside Europe. For the Brexit generation, the “European Union Dream” is far behind, and young people from Southern Europe are not expecting to enlarge the EU in the East while they do not want to see a powerful Russia neither. In that context, Chinese investors are welcome and especially the tourists and businessmen and women.

Thus, the arrival of China in the Black Sea is an opportunity for both Western powers and countries in the region to rethink their approach and ask themselves fundamental questions about the consequences of their divisions and rivalries. Beijing confronts the United States and the EU with their lack of pragmatism and their reluctance to adopt a new approach towards frozen conflicts in the region. A similar situation with Russia, unable to generate a constructive dialogue in the post-Soviet space, finds itself in a pattern of Chinese dependence while ensuring the security of the infrastructure that does not belong to it. What is the future of Sino-Russian and Sino-EU relations in the Black Sea? Nobody can tell for sure at the moment, even if it seems obvious farming, wine, and post-Soviet industrial sector have all reasons to focus on China instead of the EU and Russian markets.

Bibliography

Klimenko Ekaterina, Protracted Armed Conflicts in the Post-Soviet Space and their Impact on Black Sea Security, SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security, n° 2018/8, 2018.

LAMBERT Michael Éric, China Grand Strategy in the Black Sea Region», Vox Collegii, vol. XVI, 2017, Collège de Défense de l’Otan.

MAKOCKI Michal et Popescu Nico, China and Russia: an Eastern partnership in the making?, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Chaillot Paper n° 140, 2016.

MÜNSTER Katharina, Chinas 16+1-Kooperation mit Osteuropa: Trojanisches Pferd ohne volle Besatzung, Arbeitspapier Sicherheitspolitik, n° 6/2019.

PRZYCHODNIAK Marcin, China’s Perspective on Its Strategic Partnership with Russia, Bulletin n° 60, Polish Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

Revue Défense Nationale n° 811, L’Empire du Milieu au cœur du monde : Stratégie d’influence et affirmation de la puissance chinoise, 2018.