Moscow is clearly not interested in claiming any of the disputed waters, islands or reefs of the South China Sea. Still, it pursues its own stake, which is mainly linked to its economic and strategic interests.

Despite not being directly involved in the territorial dispute, Moscow still plays a double role. On the one hand, it has been pursuing a strategy of hedging within that specific regional complex. The People’s Republic of China is not the only country which collaborates with Russia in that area. Vietnam, for instance, appears to be the Russian gate to South-East Asia, both in economic and security terms. The Philippines is another country with which Russia has been cooperating in the energy field. In 2019, President Duterte asked Russia to carry out offshore oil and gas exploration in what he defines the “West Philippine Sea”, namely the South China Sea, once again placing Moscow at the center of the dispute.

Imagining Russia’s actions in the South China Sea as mere hedging measures in order to preserve geopolitical stability in a crucial region would be a huge mistake. As the West continues to perceive Moscow and Beijing as systemic rivals, the reverse is also true.

Moscow is, of course, not the only one balancing here. China fears a U.S. intervention too. In fact, despite Moscow’s military cooperation with Hanoi, Beijing appears to coexist with it, as it prevents Vietnam from aligning with Washington.

Troubled waters in South China Sea

The waters of the South China Sea are troubled. The latest weeks have not been that quiet in that geopolitical area. On the one side, the Spratly Islands continue to be under the spotlight, as Chinese vessels have been detected by the Philippines within its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). On the other side, Manila’s coast guard has lately been engaged in a naval drill in the disputed waters. President Duterte clearly stated that he will not undermine his country’s sovereignty by withdrawing its vessels from patrolling national waters.

As tensions mount, Vietnam is not twiddling its thumbs. Lately, Hanoi has in fact been building up its own maritime militia, which patrols the area around Hainan, the Spratly and the Paracel Islands. China believes this to be a covert operation in order to spy on the Chinese military infrastructure and ships.

Russia’s stake in the wrangle

Located thousands of kilometers away, Russia may look like a full-fledged outsider of this dispute. Still waters run deep. Back in 2016, Vladimir Putin spoke of a “greater Eurasian partnership”. As the Russian Federation has been engaged in its pivot to Asia for almost ten years, links with a number of major Asian countries—both bilaterally and multilaterally through organizations (like the Eurasian Economic Union, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or ASEAN)—are strong and definite.

Moscow is clearly not interested in claiming any of the disputed waters, islands or reefs of the South China Sea. Still, it pursues its own stake, which is mainly linked to its economic and strategic interests.

Only by going beyond official rhetoric, one can possibly understand Russia’s goals within this geopolitical context. During the 2016 G20 Summit in China, Vladimir Putin clearly stated that any third-party interference within this quarrel would becondemned by Russia.

According to the official statements, Moscow advocates for a peaceful resolution of the dispute among the parties involved. The Russian Federation stands firm on the adherence to international law and UNCLOS, while supporting the 2002 ASEAN-China Joint Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.

The latest years have been fruitful for Russia’s economic links with several Asian and South-East Asian countries. Let’s just think about its relations with the main claimants within this dispute. Moscow is the leading trade partner with Vietnam, has secured itself a close and comprehensive partnership with China and is clearly interested in deepening its ties with ASEAN countries.

As Russia is not a newborn in the energy and defense sectors, it tries to take advantage of its skills in order to get the most of it within this region, too. However, this has to do not with economic concerns only. Security matters just as well.

Between Hanoi, Manila, New Delhi and Beijing

Despite not being directly involved in the territorial dispute, Moscow still plays a double role. On the one hand, it has been pursuing a strategy of hedging within that specific regional complex. On the other hand, the disputed South China Sea must be understood within a larger systemic framework of international relations.

By using the term “hedging”, we refer to as a set of intertwining policies between engagement, integration and containment with the aim of bumping up one’s security. As different regional actors are involved, this is the strategy that Russia has so far used in order to preserve a sort of geopolitical stability.

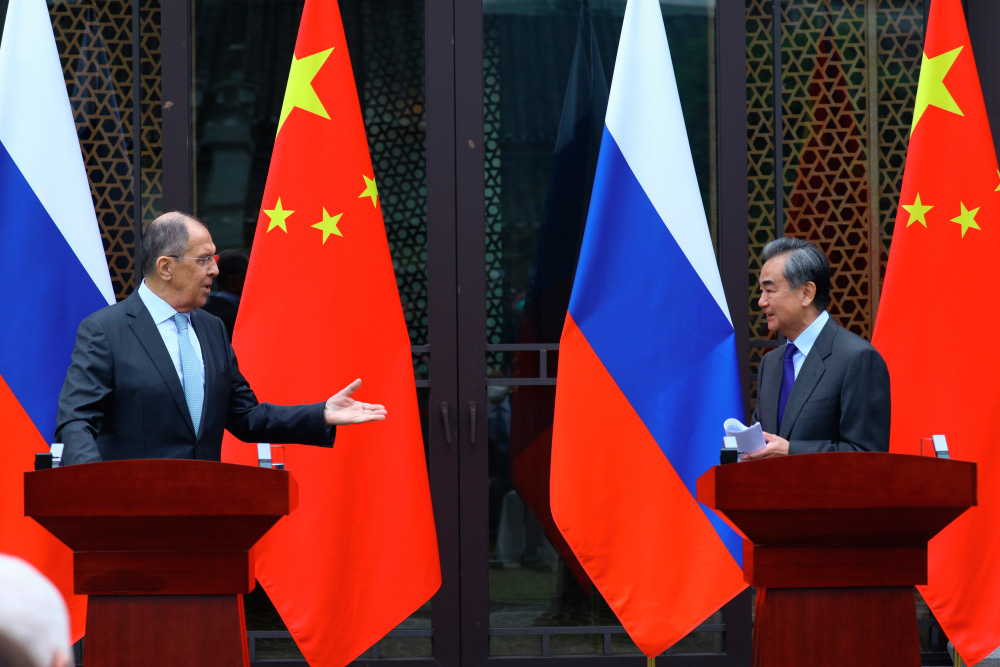

The People’s Republic of China undoubtedly represents the most crucial player in the dispute. The latest months have confirmed how deep the comprehensive and strategic partnership between Beijing and Moscow is. Just some time ago, the two countries announced a joint project for a moon research station and increased cooperation within the joint venture Arctic LNG-2. Cooperation in the defense field has been sped up too. Not so long ago, Beijing has purchased some of Moscow’s top military technologies, such as Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets and S-400 anti-missile systems.

In 2016, the two parties have carried out a joint naval drill in the waters of the contested South China Sea. This was interpreted by the international community as the expression of Russia taking the Chinese side. The same year, the Hague International Court spoke out in favor of the Philippines, ruling that the Chinese territorial claims were unfounded. This happened at a time when Russia could possibly face the same situation with Crimea, so the Russian rhetoric of external non-interference within conflicts was reiterated, as had already been the case with the Western engagement in Libya or Iraq.

Even if in Hangzhou Vladimir Putin chose to publicly express his support on China about the international ruling, Russia continues to flaunt its neutral stance. For instance, Moscow has never publicly supported China’s concept of the nine-dash line, since the Chinese concept of establishing sovereignty on account of historical rights clearly contradicts international law. Still, this may be a source of disagreement, as China does not fully recognize the same idea for what concerns Russian claims in the Arctic.

The People’s Republic of China is not the only country which collaborates with Russia in that area. Vietnam, for instance, appears to be the Russian gate to South-East Asia, both in economic and security terms. Crucial energy and economic deals have been signed between the two parties—not only within the Eurasian Economic Union.

Lukoil, Gazprom and Rosneft have been deeply involved in the development of oil and gas fields also within the disputed waters of the South China Sea, much at China’s discontent. In 2018, the Russian state oil company, Rosneft, initiated drilling in the Lan Do “Red Orchid” offshore gas field. The Chinese Foreign Ministry harshly replied by condemning this act.

The reminiscence of the Cold War has become the foundation for integration between the two countries in the defense field as well. In 2012, the entente was elevated up to the grade of a comprehensive strategic partnership. With the situation in the South China Sea worsening, Hanoi has lately been expanding its arms purchases from Russia, as it has happened with the Project 1241 corvettes. Beyond arms sales, Russia plays a major role in fostering the Vietnamese military capabilities, which are also aimed at countering any threat within the South China Sea.

The Philippines is another country with which Russia has been cooperating in the energy field. In 2019, President Duterte asked Russia to carry out offshore oil and gas exploration in what he defines the “West Philippine Sea”, namely the South China Sea, once again placing Moscow at the center of the dispute.

Countering the systemic threat

Imagining Russia’s actions in the South China Sea as mere hedging measures in order to preserve geopolitical stability in a crucial region would be a huge mistake. As the West continues to perceive Moscow and Beijing as systemic rivals, the reverse is also true.

The United States’ reorientation towards Asia under President Obama has been considered as a sort of systemic pressure on Russia. Through Moscow’s lenses, Washington is seeking to maximize its influence in the dispute and in the area by strengthening ties with its Asian partners as well as through the QUAD format. This is also shown by the U.S. willing to modernize its military bases in Okinawa and Guam. This is why Moscow would like to resist the so-called “internationalization” of the conflict, as claimed by Korolev.

Moscow has in fact been helping Hanoi in modernizing a former Cold War base at Cam Ranh Bay by supplying Kilo submarines and providing training programs. In November 2014, an agreement was signed permitting to use this naval facility by Russian military forces. This led to a quarrel with the United States, as Russian bombers were patrolling over an area too close to Guam. Russia’s interest in reestablishing a permanent presence in the South China Sea is thus also directed against the United States’ aspirations in the area and represent a real balancing strategy.

Moscow is, of course, not the only one balancing here. China fears a U.S. intervention too. Aleksander Korolev has an interesting intuition on the issue. In fact, despite Moscow’s military cooperation with Hanoi, Beijing appears to coexist with it, as it prevents Vietnam from aligning with Washington.

At the end of the day, Russia—despite its geographic location and seemingly neutral stance—does care about the South China Sea dispute and has a role in it indeed. Keeping a low profile does not necessarily mean indifference. At least, this is not the case.

References

1. Adnan, M., & Shahid, F. (2020). South China Sea Dispute: China's Role and Proposed Solutions. Journal of Political Studies, 27(1), 205-220.

2. Blank, S. (2018). Paradoxes Abounding: Russia and the South China Sea Issue. In Corr, Anders (ed), 2018, Great Powers, Grand Strategies: The New Game in the South China Sea Naval Institute Press, 1-14.

3. Dikarev, A., & Lukin, A. (2020). Russia’s approach to South China Sea territorial dispute: it’s only business, nothing personal. The Pacific Review, 1-30.

4. Korolev, A. (2019). Russia in the South China Sea: balancing and hedging. Foreign Policy Analysis, 15(2), 263-282.

5. Lee, W. C. (2017). Introduction: the South China Sea Dispute and the 2016 arbitration decision. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 22(2), 179-184.