The Media System Within and Beyond the West: Australian, Russian and Chinese Media

(votes: 6, rating: 3.5) |

(6 votes) |

PhD student in Media and Communication, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

This article takes Australian, Russian and Chinese media as three examples to differentiate media systems and elucidate their political or economic context to understand media systems globally. Arguably, the concept of media systems " does not possess a normative or even generally accepted definition", mainly because the notion is posited on existing publications and empirical research rather than normative theory. More precisely, "this is so for two reasons: firstly—because of the term's content specificity; secondly—because it is dynamic and variable in time and therefore difficult to precisely define".

Drawing on the current research of advanced capitalist democracies in Western Europe and North America, Hallin and Mancini propose "there are two main elements of the conceptual framework of Comparing Media Systems (setting aside political-social system variables): the set of four "dimensions" of comparison, and the typology of three models that summarizes what we see as the distinctive patterns of media system development among our 18 cases". Furthermore, they clarify the four major dimensions that can be compared in different media systems: "first, the development of media markets, with particular emphasis on the strong or weak development of a mass circulation press; second political parallelism; that is, the degree and nature of the links between the media and political parties or, more broadly, the extent to which the media system reflects the major political divisions in society; third, the development of journalistic professionalism; and fourth, the degree and nature of state intervention in the media system".

Hallin and Mancini illustrate that Australia should be another example of the Liberal Model. It is because firstly, the "Liberal Model is the broadest, attempting to bridge the trans-Atlantic gulf that regularly emerges in the comparative literature". Secondly, Australia has historical connections with the UK and the US regarding "early democratization and highly professionalized information-based journalism". This association has led to strong characteristics of Anglo-American conventions in the Australian media structure, with the quintessence of a dual media system. The binary design has combined the UK-style PSBs (public service broadcasters) such as ABC and SBS (Special Broadcasting Service) with the "US-style commercial networks". Thirdly, Australia is famous for one of the highest commercial media ownership concentration rates globally, particularly in the newspaper area.

After the disintegration of the USSR, Russia took a series of measures to adopt elements of the Western media apparatus, such as "abolition of censorship, freedom of press concepts and related legislation, privatization of media, a shift to more objective reporting, and increasing control by journalists and editorial boards over news production". However, arguing that the Russian media have been westernized only shows "a poor understanding of" the legacy of the Soviet Union and the "complexity and dissimilarities of the post-Soviet society", ignoring the most influential factor in the Russian media system: the state. Arguably, the interplay between the state and media has defined the essence and main features of the Russian media system. Historically and culturally, "in Russian public communications, relations between the state and a citizen have involved a clear subordination of the individual to a social power that has always been associated in the Russian context with the state.

If there is still a likelihood to compare the Russian media system with the Mediterranean Model due to a certain extent of similarities, "bringing the Chinese media system into a worldwide comparative project is to bring one of the most dissimilar systems into the non-Western empirical reality". Furthermore, if the role above of the state in the Russian media system can be portrayed as "strong influence", the Chinese state's position or the sole ruling party CPC in its media apparatus should be regarded as dominant. As mentioned, regarding the political news, Russians still enjoy some freedom in less influential media. In contrast, there is no autonomy in the Chinese press, with the omnipresent regulative measures such as media censorship and the internet Great Firewall in China. Thus, considering the state's special role, the Chinese media system is far beyond the intervention framework in the West.

This article takes Australian, Russian and Chinese media as three examples to differentiate media systems and elucidate their political or economic context to understand media systems globally. Arguably, the concept of media systems "does not possess a normative or even generally accepted definition", mainly because the notion is posited on existing publications and empirical research rather than normative theory. More precisely, "this is so for two reasons: firstly—because of the term's content specificity; secondly—because it is dynamic and variable in time and therefore difficult to precisely define".

Drawing on the current research of advanced capitalist democracies in Western Europe and North America, Hallin and Mancini propose "there are two main elements of the conceptual framework of Comparing Media Systems (setting aside political-social system variables): the set of four "dimensions" of comparison, and the typology of three models that summarizes what we see as the distinctive patterns of media system development among our 18 cases". Furthermore, they clarify the four major dimensions that can be compared in different media systems: "first, the development of media markets, with particular emphasis on the strong or weak development of a mass circulation press; second political parallelism; that is, the degree and nature of the links between the media and political parties or, more broadly, the extent to which the media system reflects the major political divisions in society; third, the development of journalistic professionalism; and fourth, the degree and nature of state intervention in the media system".

Drawing on the four dimensions, Hallin and Mancini summarize three modules from Western Europe and North America: "the Mediterranean or Polarized Pluralist Model, the North/Central European or Democratic Corporatist Model,

and the North Atlantic or Liberal Model", which will be elaborated on by the next tables.

Table 1 Mediterranean or Polarized Pluralist Model

| Country Examples | France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain |

|---|---|

| Newspaper Industry | Low newspaper circulation; elite politically oriented press |

| Political Parallelism | High political parallelism; external pluralism, commentary-oriented journalism; parliamentary or government model of broadcast governance—politics-over-broadcasting systems |

| Professionalization | Weaker professionalization; instrumentalization |

| Role of the State in Media System | Strong state intervention; press subsidies in France and Italy; periods of censorship; "savage deregulation" (except France) |

Table 2 North/Central European or Democratic Corporatist Model

| Country Examples | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland |

|---|---|

| Newspaper Industry | High newspaper circulation; early development of mass-circulation press |

| Political Parallelism | External pluralism, especially in the national press; historically strong party press; a shift toward neutral commercial <p>press; the politics-in-broadcasting system with substantial autonomy |

| Professionalization | Strong professionalization; institutionalized self-regulation |

| Role of the State in Media System | Strong state intervention but with protection for press freedom; press subsidies, robust in Scandinavia; strong public-service broadcasting |

Table 3 North Atlantic or Liberal Model

| Country Examples | Britain, the United States, Canada, Ireland |

|---|---|

| Newspaper Industry | Medium newspaper circulation; early development of mass circulation commercial press |

| Political Parallelism | Neutral commercial press; information-oriented journalism; internal pluralism (but external pluralism in Britain); professional model of broadcast governance—formally autonomous system |

| Professionalization | Strong professionalization; noninstitutionalized self-regulation |

| Role of the State in Media System | A market dominated (except strong public broadcasting in Britain, Ireland) |

Source: created by the author of this thesis and based on Hallin and Mancini.

Furthermore, it is unfeasible to simply apply the conceptual framework to other countries without appropriate modification. In fact, the "four dimensions" and "three models" are just perfect types, only loosely matched by the media systems of different countries. The ultimate purpose is not to classify individual media systems but to identify the "characteristic patterns of relationship between system characteristics". Consequently, these inherent patterns of media systems offer "a theoretical synthesis and a framework for comparative research on the media and political systems".

The Australian media system as an outlier in the Liberal Model

Hallin and Mancini illustrate that Australia should be another example of the Liberal Model. It is because firstly, the "Liberal Model is the broadest, attempting to bridge the trans-Atlantic gulf that regularly emerges in the comparative literature". Secondly, Australia has historical connections with the UK and the US regarding "early democratization and highly professionalized information-based journalism". This association has led to strong characteristics of Anglo-American conventions in the Australian media structure, with the quintessence of a dual media system. The binary design has combined the UK-style PSBs (public service broadcasters) such as ABC and SBS (Special Broadcasting Service) with the "US-style commercial networks". Thirdly, Australia is famous for one of the highest commercial media ownership concentration rates globally, particularly in the newspaper area.

However, the Australian media system does not offer the quintessence of the Liberal Model. Jones and Pusey apply the Liberal Model to the Australian media system and identify four remarkable discrepancies. More precisely, compared to the Liberal Model, Australia has "historically late professionalization of journalism; comparatively low levels of education of journalists; low per capita investment in PSBs; poor regulation for accuracy and impartiality of commercial broadcast journalism; and slow development of relevant bourgeois liberal institutional conventions and rational-legal authority, e.g., formal recognition of freedom of the press".

Furthermore, Jones and Pusey contend that Australia has several similar features with the Polarized Pluralist Model, especially in clientelism. Based on the definition of Hallin and Mancini, "clientelism tends to be associated with instrumentalization of both public and private media. In the case of public media, appointments tend to be made more based on political loyalty than purely professional criteria". More concretely, Jones and Pusey outline the following examples to indicate the similarities of the Australian media system with the Polarized Pluralist Model: "the widely accepted recognition that appointments to the ABC Board have been more often than not party-political; the infamous 'Murdoch amendments' by the Fraser government to broadcasting legislation in the late 1970s to facilitate Murdoch's concentration of television ownership; and the long history of proprietorial intervention in the political world".

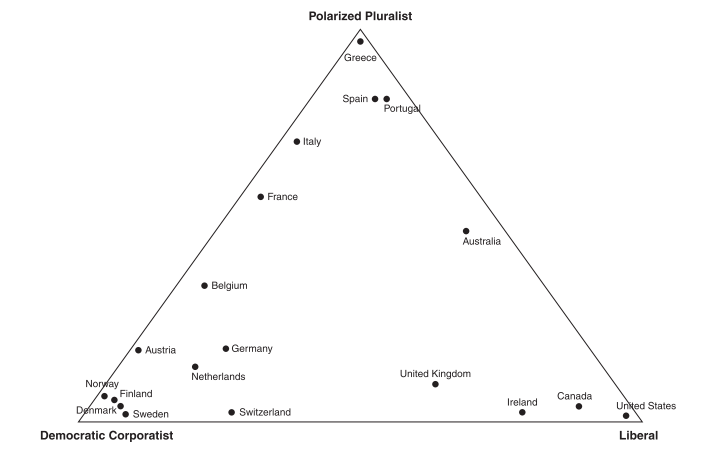

Thus, to this extent, there is a certain degree of political parallelism in the Australian media system. However, the Australian one does not match the Polarized Pluralist Model in some key areas. More precisely", Australia does not have a highly polarized political culture and a strong tradition of mass-circulation party newspapers". Therefore, it is arguable to perceive the Australian media system as an outlier of the Liberal Model, which can be shown in the following figure:

Figure 1 Relation of individual cases to the three models

Source: derived from Jones and Pusey.

Beyond the West: the unique Russian and Chinese media model

Although the Australian media system is an outlier in the Liberal Model, it still belongs to the typology and scope of the three models, posited on the empirical reality of Western Europe and North America. However, bringing the Russian and Chinese media models into this global comparative apparatus involves two distinct and peculiar systems into the Western-centric framework. Thus, the three models' classification cannot apply to Russia and China's two unique systems. Nevertheless, the four dimensions of comparison as a tool for analyzing systemic characteristics still work. However, they are not perfect and need to be modified in the application, as mentioned before.

The Russian media system as a statist commercialized model

After the disintegration of the USSR, Russia took a series of measures to adopt elements of the Western media apparatus, such as "abolition of censorship, freedom of press concepts and related legislation, privatization of media, a shift to more objective reporting, and increasing control by journalists and editorial boards over news production". However, arguing that the Russian media have been westernized only shows "a poor understanding of" the legacy of the Soviet Union and the "complexity and dissimilarities of the post-Soviet society", ignoring the most influential factor in the Russian media system: the state. Arguably, the interplay between the state and media has defined the essence and main features of the Russian media system. Historically and culturally, "in Russian public communications, relations between the state and a citizen have involved a clear subordination of the individual to a social power that has always been associated in the Russian context with the state".

Thus, even though the Polarized Pluralist Model is the most similar of the three models to the Russian one, the Russian media system is still far from the Mediterranean apparatus. The Russian state's role has exceedingly overshadowed that of the Mediterranean states, suggesting that they cannot be classified as the same type. Ivanitsky differs the Russian media system from the Polarized Pluralist Model in that "it is the state which defined the particular journalism modes such as Court journalism, Imperial journalism, Communist Party journalism in Russian history. Currently, while liberating the media's economic activity, the state is not ready to relax the control over the content".

This overwhelming influence of the state also reflects in Russian political parallelism. Although new political parties have appeared after the formation of the Russian Federation, Oates argues that "rather than encouraging the growth and the development of a range of political parties, media outlets in Russia have worked at supporting relatively narrow groups of elites", part of which have been formed due to the privatization. These elites, combining old political and new emerging business elites, "became key players in the media scene". More concretely, they created "a particularly Russian form of political parallelism" by using "political media as traditional instruments of political elite management". Besides, due to the dominant role of the state in Russia, "media, particularly television, have been used to subvert the development of a pluralistic party system".

Furthermore, in terms of the media industry, the influence of the state is also ubiquitous. Ivanitsky believes the state "has produced practically unsolvable tension for the media themselves trying to function both as commercial enterprises and as institutions of the society", even though Russia has achieved rapid development in its advertising and media market. Hypothetically, these tensions between the media and the state are supposed to be the "decentralized market competition as a vital antidote to political despotism". However, Vartanovaargues that "the aims of the state converged with those of the advertising industry, and commercially determined content became both a means of increasing depoliticization and instrumentalization of political communication, and of stimulating consumption". From another angle, de Smaele believes that the Western influence on Russian media has only been limited to market demand, with the lack of Western notions such as "independent Fourth Estate".

As for Russia's professionalization, "journalism as a profession had a rather late start" with a strong censorship history, thus resulting in a self-censorship tradition until now. Another factor contributing to the self-censorship is that "formally declared freedom and autonomy of media professionals came into conflict with the efforts of the new owners", deeply connected to the state and political elites, "to use these new professional values to further their own interests" rather than the public interests and social responsibility. Thus, to notch economic successes and avoid potential political risks, Russian journalists have become increasingly market-driven and apathetic to politics. Due to the different "professional identity", Russian journalists have a dissimilar "literary style and attitude to facts and opinions", which has restrained them from integration into Western journalism.

However, this statist media policy does not mean there is no freedom regarding the Russian media system's political news. Admittedly, the state has strong influences on "television channels with national distribution", which has been regarded as "the main source of information about Russia and the world". By comparison, the pressure of the state has become weak and even non-existent in some less disseminated areas such as the television channel "REN-TV", the radio station "Ekho Moskvy", and the newspapers "Novaya Gazeta", "Nezavisimaya Gazeta" and "Kommersant", as well as almost the whole of the internet.

Therefore, it is possible to say that the duality of authoritarian attitudes to mass media and journalism—a statist media policy deeply rooted in the framework of state influence on media combined with the growing market-driven economy—has become the most crucial characteristic of the Russian media system". To this extent, the Russian media system can be described as a statist commercialized model.

The Chinese media system as a state-dominated model

News is Not about Catchy Headlines

If there is still a likelihood to compare the Russian media system with the Mediterranean Model due to a certain extent of similarities, "bringing the Chinese media system into a worldwide comparative project is to bring one of the most dissimilar systems into the non-Western empirical reality". Furthermore, if the role above of the state in the Russian media system can be portrayed as "strong influence", the Chinese state's position or the sole ruling party CPC in its media apparatus should be regarded as dominant. As mentioned, regarding the political news, Russians still enjoy some freedom in less influential media. In contrast, there is no autonomy in the Chinese press, with the omnipresent regulative measures such as media censorship and the internet Great Firewall in China. Thus, considering the state's special role, the Chinese media system is far beyond the intervention framework in the West.

In fact, despite Deng Xiaoping's reform, the Chinese media system of the post-Mao period has still applied the "different versions of Marxism and socialism" to "build socialism with Chinese characteristics" by "providing moral guidance to the population and engineering economic development and social change". One of the most important reasons that may clarify this "guidance", namely, strong and resilient media control, is the media ownership in China. It is undeniable that the post-Mao economic reforms have expanded the private capital to some areas that had been commanded by the Chinese government or state-owned enterprises for decades. However, Zhao argues that "in the media sector, although the Chinese state has not only drastically curtailed its role in subsidizing media operations but has also targeted the media and cultural sector as new sites of profit-making and capitalistic development, the state continues to restrict private capital, let alone the privatizing of existing media outlets".

In fact, the Chinese state has opened the door to private and even foreign capital participation in "the media's entertainment function" such as the film industry with the intention of profit-making. However, this profit-making entertainment also needs to be filtered by the ideological orientation of the state. More importantly, "the production and distribution of news and informational content" and the "ownership of news media outlets" have remained "monopolized by the state". Furthermore, this monopoly also results in the fact that the state has appointed major media agencies' leadership.

Despite the state's overwhelming control, the Chinese media market has boomed for years since the economic reform of Deng Xiaoping, attributable to the power of marketization. For instance, in 2004, there were 6,580 daily newspapers published worldwide, and the number of daily newspapers published in China ranked first in the world, accounting for 14.5% of the global daily newspapers. However, the commercialization of the Chinese media industry has not surmounted the ideological control of the state. The media market has constituted "two distinct and yet institutionally intertwined press sectors or subsystems". The first press sector is market-based as the film above industry, while the second is "the party organ sector", which combines the duality of the political instrument and profit-making. This is because "most state media outlets no longer receive large government subsidies and have largely to depend on commercial advertising". Nevertheless, rather than causing tensions, the dual roles the party organ sector plays have adopted and contained the marketization within the current political control by the statist implementation of "licensing system and the sponsor unit system". Consequently, these two systems have guaranteed the predominance of the state over the commercialization and marketization.

As for the political parallelism, the state-dominated Chinese media system has top-level political instrumentalization, indicating "all the features of a quintessential party-press parallelism". Almost all the media content should and, in practice, have revolved around the official ideology and slogan of the state. This is pertinent to another aspect of four dimensions, based on the theory and standard of Hallin and Mancini: the utterly low professionalization in Chinese journalism, where journalists have to successfully balance the "market forces and the party-press system" to obtain financial benefits and political security. Furthermore, Pan and Lu argue that Chinese journalists "do not fit their practices into the universal model of professionalism", but "utilize and appropriate diverse and often conflicting ideas of journalism through their improvised and situated practices", leading to the "truncated and fragmented in Chinese journalism". Also, unlike the Western conception of relative objectivity in journalism, Hackett and Zhao create a term "regime of objectivity" to describe how Chinese journalists portray information on the precondition of conforming to the state ideology.

Therefore, due to its restricted commercialization and dominated state, Chan summarizes the Chinese media industry's development as commercialization without independence. Drawing on the above, the Chinese media system can be described as a state-dominated model.

References

Chan, Joseph Man. "Commercialization without Independence: Trends and Tensions of Media Development in China". In China Review 1993, edited by Joseph Cheng Yu-shek and Maurice Brosseau, 25.1 - 25.21. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 1993.

de Smaele, Hedwig. "The Applicability of Western Media Models on the Russian Media System". European Journal of Communication 14, no. 2 (1999): 173-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323199014002002.

Dunn, John A. "Lottizzazione Russian Style: Russia's Two-Tier Media System". Europe-Asia Studies 66, no. 9 (2014): 1425-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.956441.

Hackett, Robert A., and Yuezhi Zhao. Sustaining Democracy? Journalism and the Politics of Objectivity. Edited by Yuezhi Zhao. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Higher Education, 2000.

Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Communic

ation, Society and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.———. "Ten Years after Comparing Media Systems: What Have We Learned?". Political Communication 34, no. 2 (2017): 155-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1233158.

Hu, Zhengrong, Peixi Xu, and Deqiang Ji. "China: Media and Power in Four Historical Stages". In Mapping Brics Media, edited by Kaarle Nordenstreng and Daya Kishan Thussu, 166-80. London ;: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

Ivanitsky, Valerij. "Mass Media Market in Post-Soviet Russia [Рынок Сми В Постсоветской России]". Bulletin of Moscow University, no. 6. (2009): 114–31. Retrieved from http://www.ffl.msu.ru/en/research/bulletin-of-moscow-university/.

Jones, Paul K., and Michael Pusey. "Political Communication and 'Media System': The Australian Canary". Media, Culture & Society 32, no. 3 (2010): 451-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443709361172.

Keane, John. The Media and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Polity in association with Basil Blackwell, 1991.

Oates, Sarah. Television, Democracy, and Elections in Russia. Basees/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies. Abingdon, Oxon, England: Routledge, 2006.

Pan, Zhongdang, and Ye Lu. "Localizing Professionalism: Discursive Practices in China's Media Reforms". In Chinese Media, Global Context, edited by

Chin-Chuan Lee, 210-31: RoutledgeCurzon Taylor & Francis Group, 2003.Sonczyk, Wieslaw "Media System: Scope—Structure—Definition". Media Studies 3, no. 38. (2009). Retrieved from http://mediastudies.eu/.

Sosnovskaya, Anna. Social Portrait and Identity of Today's Journalist: St. Petersburg-a Case Study. (Södertörn Academic Studies: 2000). https://bibl.sh.se/skriftserier/hogskolans_skriftserier/Russian_reports/diva2_16051.aspx.

Tiffen, Rodney. How Australia Compares. Edited by Ross Gittins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Vartanova, Elena. "The Russian Media Model in the Context of Post-Soviet Dynamics". In Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, edited by Daniel C. Hallin and Paolo Mancini, 119-42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Wang, Guoqing. "China Newspaper Annual Development Report [中国报业年度发展报告]". People's Daily, August 5 2005. http://www.people.com.cn/.

Zhao, Yuezhi. "Understanding China's Media System in a World Historical Context". In Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, edited by Daniel C. Hallin and Paolo Mancini, 143-74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Zhou, Shuhua. "China: Media System". In, edited by W. Donsbach2015.

(votes: 6, rating: 3.5) |

(6 votes) |

In the middle between the U.S. and Russia. Interview with Eric Gujer, Editor-in-Chief at Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Make Facts Great Again: Is it Possible to Withstand Fake News?Fake news creates a vicious circle of distrust challenging both Russia and the West

Conspiracy Theories, Fake News and Disinformation. Why There’s So Much of It and What We Can Do About itReview of the report “Weapons of Mass Distraction: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age"