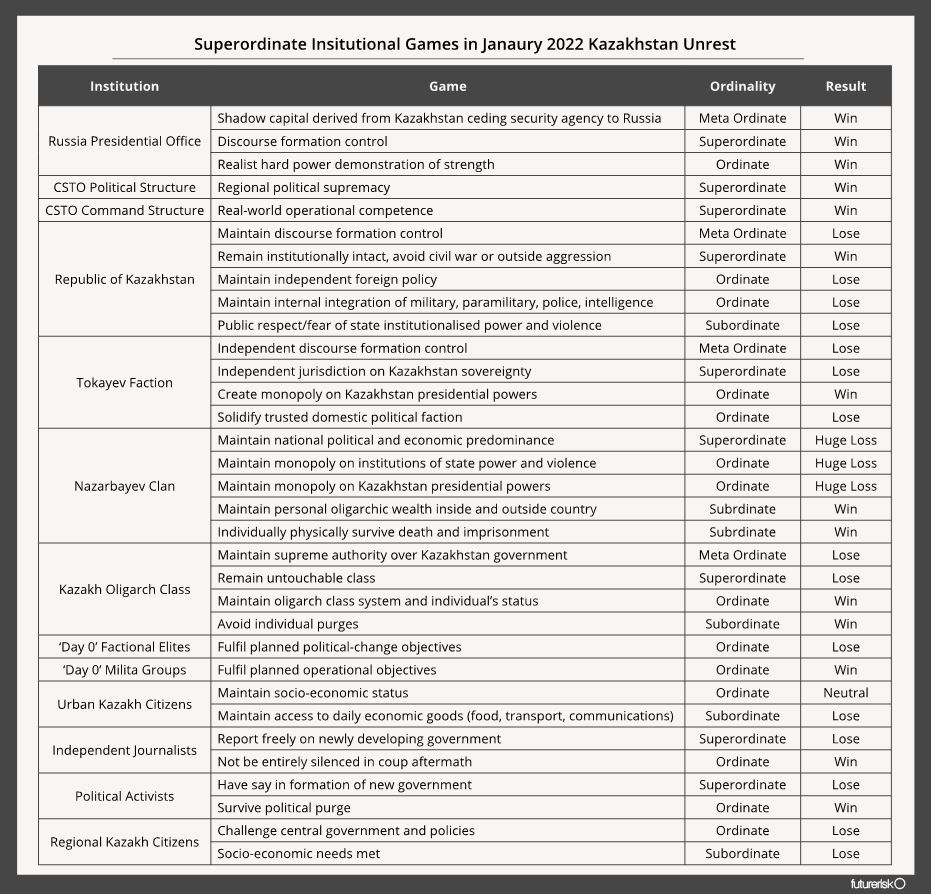

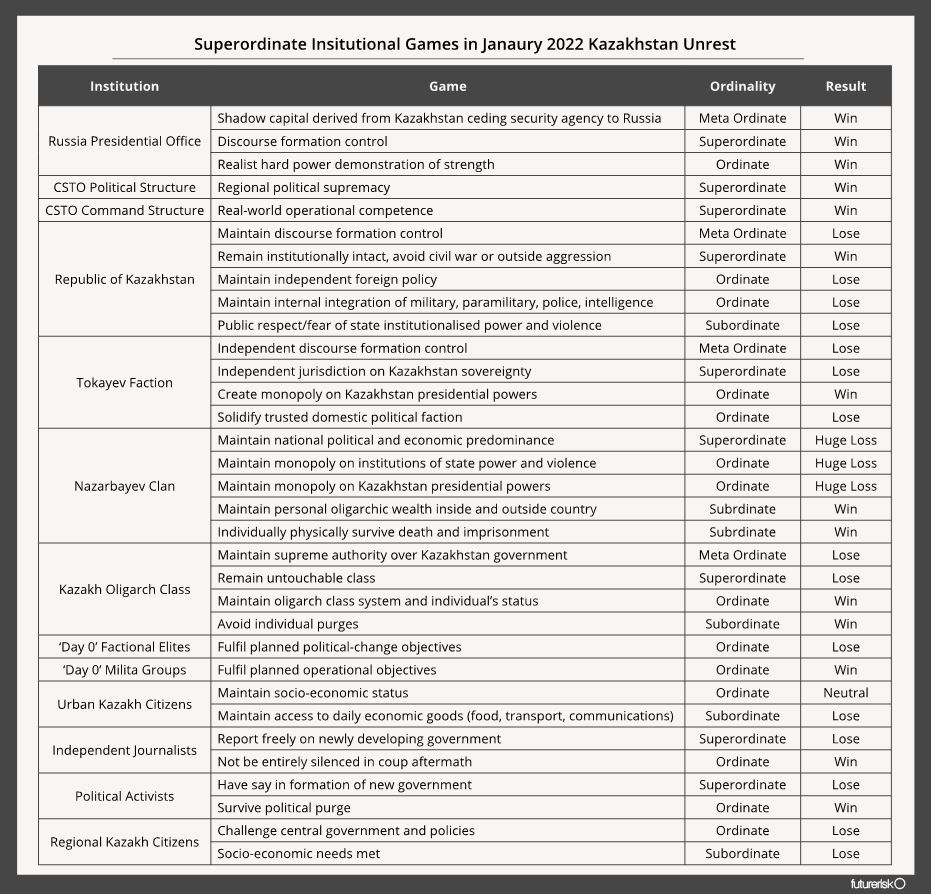

Given what is known, we assessed the institutional outcomes of the various institutional actors involved in the Kazakh unrest. This is built on a series of working analytical positions: that the Kazakh unrest was caused initially by genuine protests, was then opportunistically hijacked by as yet unknown political forces, was not an incident of terrorism, was not orchestrated or enacted by foreign forces or persons, and that whether correctly or not that President Tokayev genuinely believed a coup was imminent, that the political origin of the coup was within his own Nur Otan party, and that this is what determined the decision to call Pashinyan to invoke the CSTO to deploy Russian-led intervention forces to stabilize the governments hold on power. We categorized each of the institutional actors in the Kazakhstan unrest and assigned them one of four levels of meta, super, ordinate or subordinate political games they were deemed to be playing, and then rated them on a binary of win-lose.

The Russian institutions of state power emerged the strongest from these differentiated games, with both the Presidential Office and the CSTO attaining political capital without losing anything. For example, the CSTO proved itself to be the dominant political security paradigm in the region, and the CSTO operations at a military level were wholly successful, professional, competent. Whereas the regional, poor ethnic Kazakhs who initiated the initial protest against rising gas prices lose two ordinate and subordinate changes: no meaningful change in resource governance in Kazakhstan, and they remain orphaned from the economic growth model. Several bifurcations emerge from such an analysis, such as the differing outcomes of institutions responsible for discourse control in Russia and Kazakhstan. Analyzing Republic of Kazakhstan as having lost all games aside from maintaining institutional integrity cedes discourse formation control to the Russian institutions which enacted state power while Kazakhstan could not.

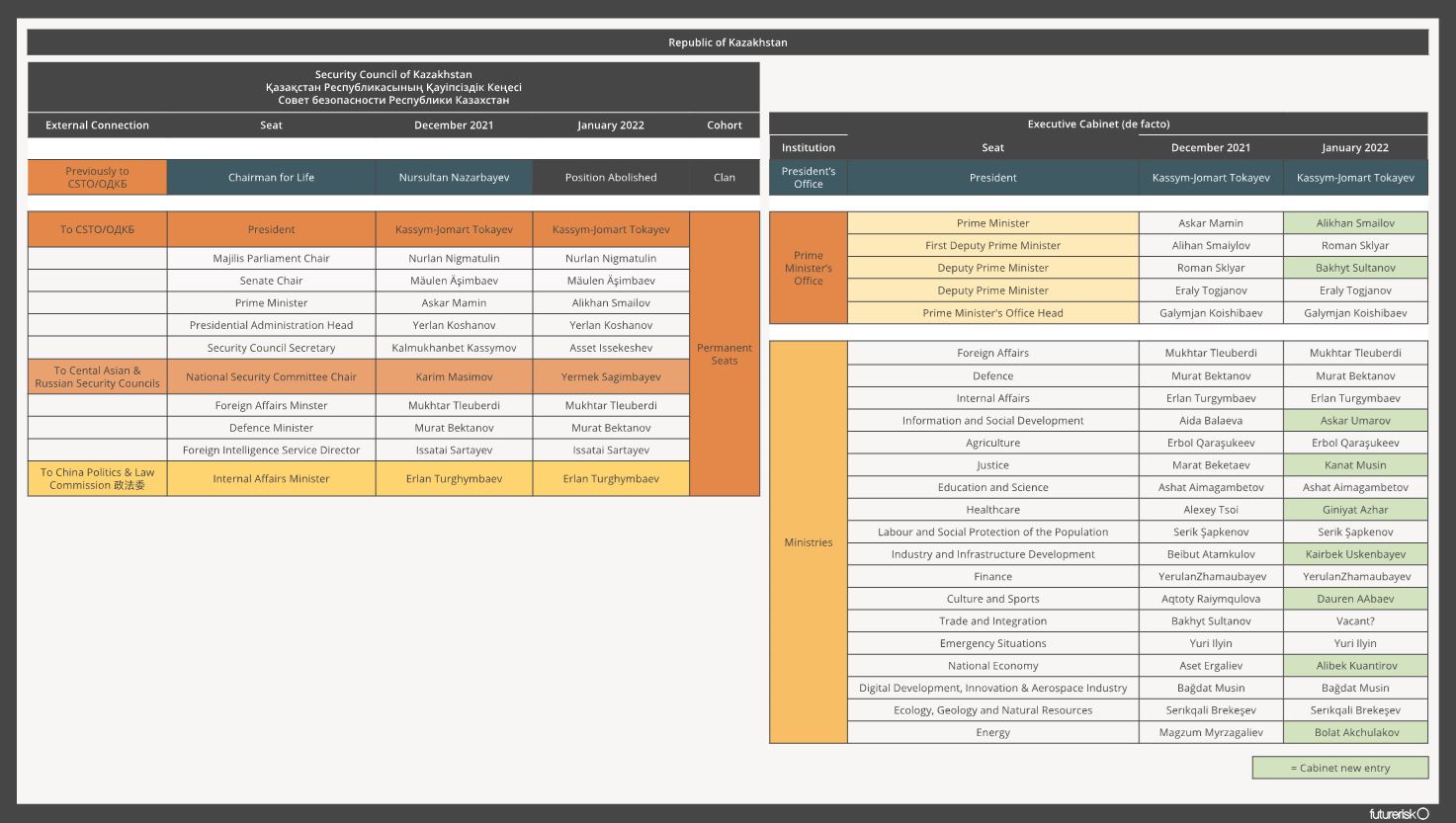

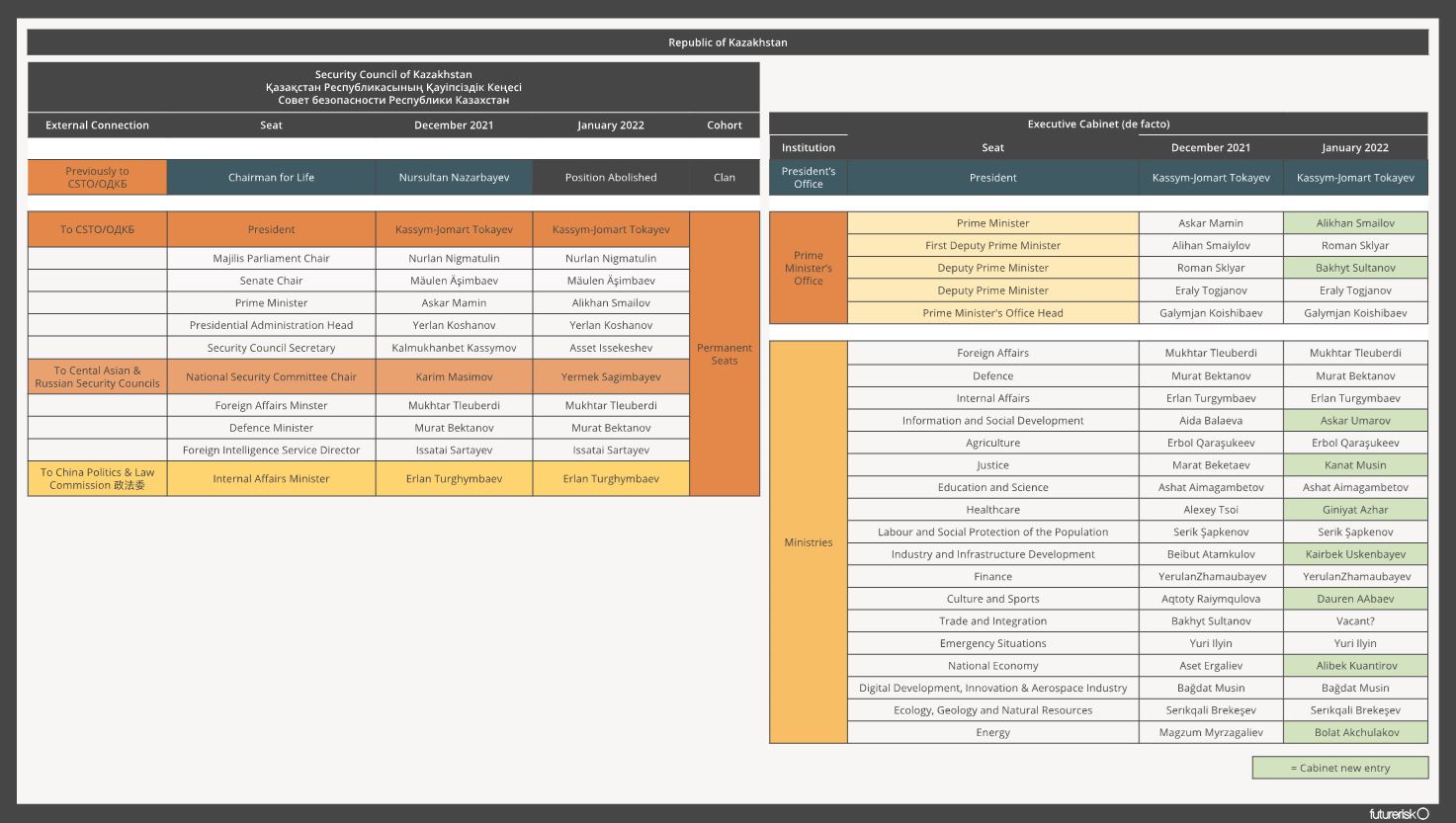

Kazakhstan’s new executive cabinet though remains very similar to the previous one. Tokayev though is still too politically weak to carry his own entourage. To hold power now, he must continue to make political compromises with personnel who benefited under the Nazarbayev clan’s rule. We have already seen with the new Security Council and cabinet picks. He cannot move strongly against the entrenched elements of the Nazarbayev clan whom he still needs to form government, and he now has the added pin of Putin backstopping security policy.

The major practical task ahead will be institutional reform of the KNB and related structures. If Tokayev can restructure the internal security apparatus this will feed into stronger institutionalized control over the National Security Council and a stronger, perhaps more competent grip on the organs of state power in Kazakhstan. From this position, Tokayev might be able to achieve some policy goals designed to assuage popular discontent. Any material benefit to the people of Kazakhstan looks years away though, and despite humiliating himself in front of Russia and China, the new Tokayev may yet prove much the same as the old Nazarbayev.

The internecine violence of intra-Party clan fighting spilled catastrophically into the streets of Almaty, opening a window to a clan power struggle which has likely sounded the death-knell of the Nazarbayevs in domestic Kazakhstan politics.

With the Kazakh government stabilized and the Russian-led CSTO force now withdrawing, the political risk scenarios surrounding Kazakhstan domestic political, social, economic, and geopolitical future are still just as opaque, complex, and institutionally multivariate. Tokayev is confirmed as still President and also now heading the Security Council for the first time after ousting Nazarbayev from a lifetime appointment. Forming a new political faction around Tokayev both through the nominally executive cabinet and through the internal control and external security institution of the Security Council though will require serious trade-offs with the now weakened Nazarbayev clan.

The Occam’s Razor of the week of social unrest and political and security turmoil was that an as yet unidentified political institution had organized a contingency plan to usurp de facto political control in the country in the event of a ‘Day Zero’ scenario. A Day Zero scenario is one in which either one or a combination of institutional factors such as a decline elite trust in executive leadership or violent anti-government popular protest create the conditions for an opportunistic seizure of power. With the aging of Nazarbayev, Day Zero scenarios mostly center on his physical incapacity and the willingness or ability of the previous ruling clan to either negotiate a transition from power, abandon their power structures, or fight to retake the dominant clan position.

That the initial protest was a legitimate public upswelling of anger primed by the removal of the LPG subsidy is well established. That the Tokayev government claim that the protests turned violent due to foreign terrorist activity is laughable. And that concurrent with the violent protests there was a power struggle at the top of the Party is almost certain from logical inference. The three black boxes that remain unanswered are: who was the second group within the protesters who turned the movement militant; who constituted which faction in the power struggle; and how much real control did they have over military and police units before the CSTO intervention was enacted? Neither of these may ever be known. Whatever the details of the militia attacks under the cover of protest, the initial public discontent cause of the protests though is now largely inconsequential.

Given what is known, we assessed the institutional outcomes of the various institutional actors involved in the Kazakh unrest. This is built on a series of working analytical positions: that the Kazakh unrest was caused initially by genuine protests, was then opportunistically hijacked by as yet unknown political forces, was not an incident of terrorism, was not orchestrated or enacted by foreign forces or persons, and that whether correctly or not that President Tokayev genuinely believed a coup was imminent, that the political origin of the coup was within his own Nur-Otan party, and that this is what determined the decision to call Pashinyan to invoke the CSTO to deploy Russian-led intervention forces to stabilize the governments hold on power. We categorized each of the institutional actors in the Kazakhstan unrest and assigned them one of four levels of meta, super, ordinate or subordinate political games they were deemed to be playing, and then rated them on a binary of win-lose.

Ordinated Institutional Games played, won and lost in the Kazakhstan unrest

The Russian institutions of state power emerged the strongest from these differentiated games, with both the Presidential Office and the CSTO attaining political capital without losing anything. For example, the CSTO proved itself to be the dominant political security paradigm in the region, and the CSTO operations at a military level were wholly successful, professional, competent. Whereas the regional, poor ethnic Kazakhs who initiated the initial protest against rising gas prices lose two ordinate and subordinate changes: no meaningful change in resource governance in Kazakhstan, and they remain orphaned from the economic growth model. Several bifurcations emerge from such an analysis, such as the differing outcomes of institutions responsible for discourse control in Russia and Kazakhstan. Analyzing Republic of Kazakhstan as having lost all games aside from maintaining institutional integrity cedes discourse formation control to the Russian institutions which enacted state power while Kazakhstan could not. Micro bifurcations exist too, for example both journalists and activists did not achieve their superordinate goals, however simply surviving and not being targeted in retributive purges is an ordinate survival win. The greatest differentiated ordinated win to loss matrix though is between the Nazarbayev Clan and the Tokayev Faction. While the Tokayev Faction has emerged still in power, both political institutions have suffered heavy losses, while still enjoying some lesser ordinate game wins.

Kazakhstan’s Dual Executive Power Structure and January Seat Reshuffle

Kazakhstan’s new executive cabinet though remains very similar to the previous one. Tokayev though is still too politically weak to carry his own entourage. To hold power now, he must continue to make political compromises with personnel who benefited under the Nazarbayev clan’s rule. We have already seen with the new Security Council and cabinet picks. He cannot move strongly against the entrenched elements of the Nazarbayev clan whom he still needs to form government, and he now has the added pin of Putin backstopping security policy. Where we can expect greater changes though are in the Security Council and in a likely future reform of the KGB-successor agency, the KNB internal security service as well as other institutions of internal security and intelligence which operate in a gray zone between military, state and party. Can Tokayev now balance creating intra-party stability, executive control of the state ministries, maintain control over the military without Russian assistance while simultaneously reforming the domestic security apparatus? Erlan Turghymbeav keeping his position as Internal Affairs minister with its position on the Security Council is perhaps an indication of the trade-offs having to be made. While it appears the noose is tightening on Nazarbayev clan members, there are many Nazarbayev loyalists within the old administration who still hold a place and a future in the Tokayev era.

Without a clear smoking barrel of the failed coup attempt though or any clear details yet of a retributive political purge, assessing the various failures of the unrest at national, party, domestic security and personnel levels remains clouded by the extremely opaque nature of the elite leadership in Kazakhstan. Coming to power in 2019 on aspirations of ruling as an economic authoritarian though, any position Tokayev’s now takes on building the national economy or reforming the oligarch class seems likely to be empty rhetoric. The major practical task ahead will be institutional reform of the KNB and related structures. If Tokayev can restructure the internal security apparatus this will feed into stronger institutionalized control over the National Security Council and a stronger, perhaps more competent grip on the organs of state power in Kazakhstan. From this position, Tokayev might be able to achieve some policy goals designed to assuage popular discontent. Any material benefit to the people of Kazakhstan looks years away though, and despite humiliating himself in front of Russia and China, the new Tokayev may yet prove much the same as the old Nazarbayev.