The South Caucasus and Southeast Ukraine are the two significant hotspots in Europe. There are still some tensions in the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict while the Georgian-Abkhaz and the Georgian-Ossetian ones are quite stable. Changes in the South Caucasus military balance have greatly affected the future of these confrontations. For Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, it is difficult to find stability because of a lack of official open-source data precludes effective conflict resolution.

Without this assessment, it is not possible to judge the prospects for freezing, settling, or the escalation of conflicts in South Caucasus. At the same time, we must not forget that Russia is actively involved in the processes in this region, both at the diplomatic and economic level and due to the military presence. We should not forget about the energy and transport infrastructure, which can suffer and be blocked during the hot phase of conflicts. Our task is to assess and compare the military potentials of the countries of the South Caucasus, as well as the level of Russia's military presence in this region to determine the likelihood and scenarios of escalation.

Comparing the two, at first glance, similar situations — the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the conflicts of Georgia with Abkhazia and South Ossetia we can see a huge difference in both political and military dispositions. In the first case, we are talking about the opposition of the parties located in approximately the same "weight class", moreover, under the scenario of hostilities limited to the territories of Nagorno-Karabakh (without involving Armenia), direct participation of Russia in the war is practically excluded. The economic and demographic advantage of Azerbaijan, besides a significant gap in the equipment and strength of the armed forces of the parties, creates certain risks of conflict escalation.

As for the Georgian-Abkhaz and Georgian-Ossetian conflicts, the security of the Russian-recognized new republics — Abkhazia and South Ossetia, is almost completely ensured by the Russian troops. Even the forces of the 7th and 4th military bases, without the involvement of additional troops, are sufficient to reliably freeze the conflict, and the current Georgian leadership does not harbor unnecessary illusions and is not investing too many resources in modernizing the armed forces. Nevertheless, even the most frozen conflict in certain conditions can go along the path of escalation. In the case of Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, this can happen only with very large regional shocks: such hypothetical and unlikely scenarios as destabilization in the Russian North Caucasus, the war of Russia and Turkey, etc. Another defrosting mechanism can be a regional war, which arose initially due to the escalation in Nagorno-Karabakh — Turkey, Russia and, less likely, Iran may be involved into a full-scale war of Armenia and Azerbaijan. This may also involve Georgia in these catastrophic processes. In this sense, the key to peace in the South Caucasus lies in Nagorno-Karabakh. The settlement or at least a deep freeze of this conflict can mitigate most of the regional military risks.

The South Caucasus and Southeast Ukraine are the two significant hotspots in Europe. There are still some tensions in the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict while the Georgian-Abkhaz and the Georgian-Ossetian ones are quite stable. Changes in the South Caucasus military balance have greatly affected the future of these confrontations. For Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, it is difficult to find stability because of a lack of official open-source data precludes effective conflict resolution.

Without this assessment, it is not possible to judge the prospects for freezing, settling, or the escalation of conflicts in South Caucasus. At the same time, we must not forget that Russia is actively involved in the processes in this region, both at the diplomatic and economic level and due to the military presence. We should not forget about the energy and transport infrastructure, which can suffer and be blocked during the hot phase of conflicts. Our task is to assess and compare the military potentials of the countries of the South Caucasus, as well as the level of Russia's military presence in this region to determine the likelihood and scenarios of escalation.

Georgia and Russia: Eternal Frost?

The August war in 2008 led to the expected military defeat of Georgia in an attempt to establish control over South Ossetia. As a result, Russia recognized the independence of Abkhazia and Ossetia. Despite the fact that the world community did not support this decision, two large Russian military bases appeared in these new republics, and their own armed forces (especially in South Ossetia) gradually integrated with them. The 7th military base in Abkhazia was established on the basis of the 131st separate motorized rifle brigade of the 58th combined army, which was the main force in August 2008. The base is armed with about 40 modernized T-72B3 tanks, at least 135 BTR-82АМ, 18 Grad MLRS, two battalions of S-300 anti-aircraft missiles (SAMs), etc. The 4th military base in South Ossetia is equally equipped to that in Abkhazia and is armed with T-72B tanks and at least 40 T-90A tanks, more than 120 BMP-2 and BMP-3 infantry fighting vehicles (IFV), BTR-82A armored personnel carriers (APC), 18 Grad and 2 Smerch MLRS, Buk-M1 medium range SAM, etc. Moreover, the border with Georgia is well fortified now. At least 7,000 people serve at the two bases, about 3000-3500 more belong to the Abkhazian and Ossetian units.

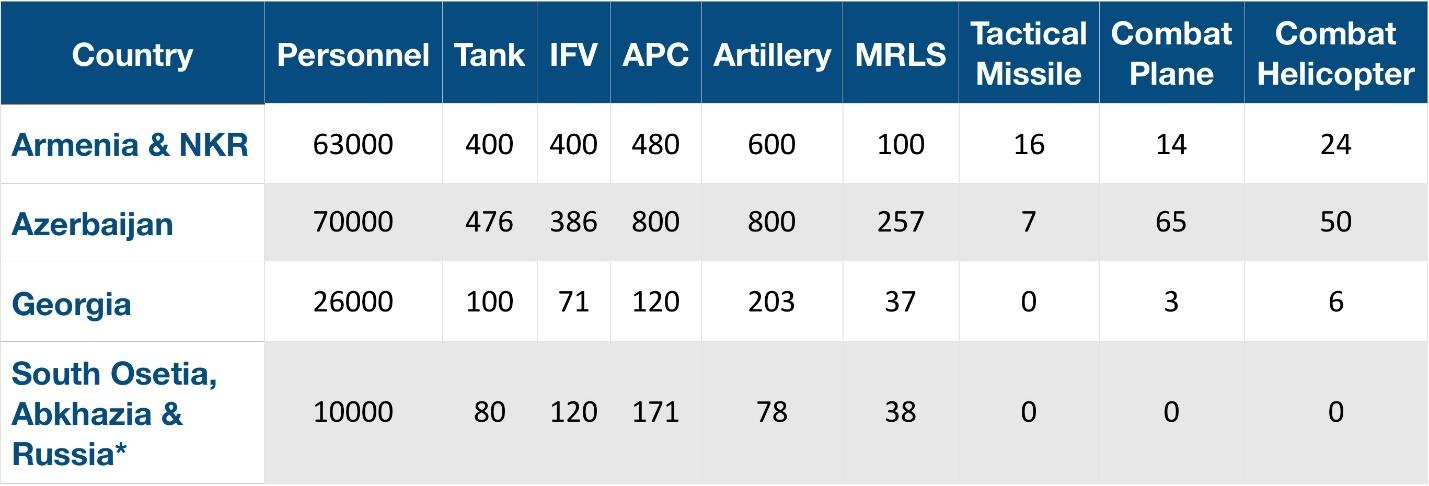

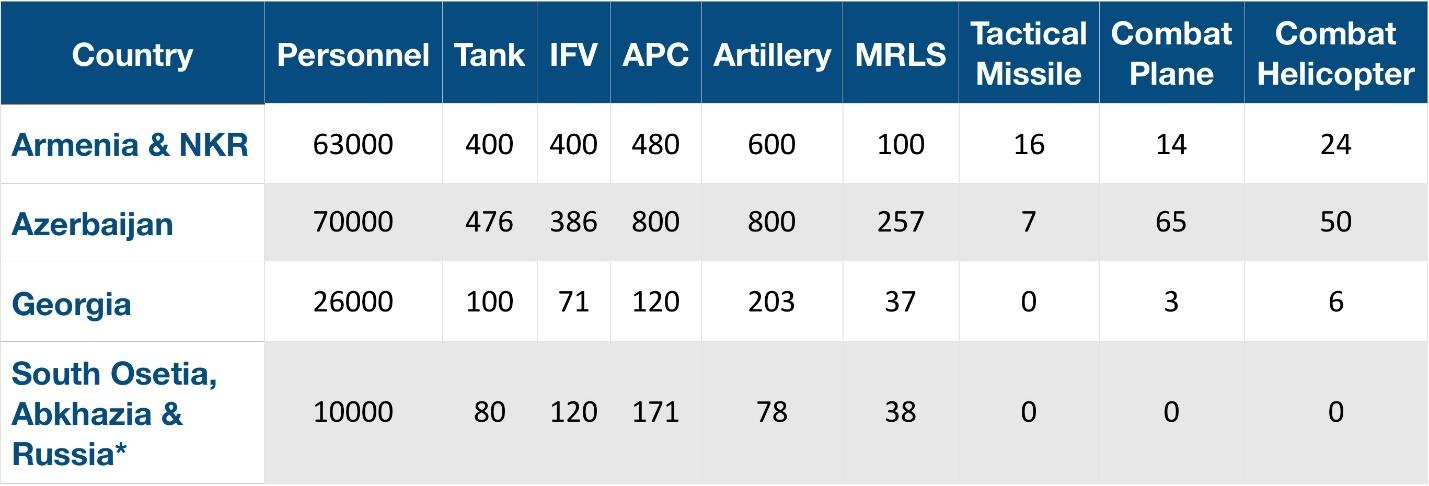

Due to the large-scale capabilities of combat aircraft, these Russian forces are enough to cease both hostilities, the resumption of which in Abkhazia and South Ossetia is only possible because of considerable destabilization, as a large-scale regional war which involves many participants. Nowadays, Russian-Georgian relations are economically stable despite quite deep Georgia-NATO relations making further escalations even less possible. There are no signs of war preparation if we take a look at how Georgia strengthened its potential and built an army after its defeat in 2008. The military budget decreased to 2% of GDP in 2017 from 8.8% and 9.1% in 2007 and 2008, respectively. There has been an almost complete degradation of attack and helicopter aircraft while heavy equipment losses during the war were only partially restored due to strictly limited foreign supplies. Georgian Armed forces are approximately 206,000 strong [1]. The army has 100 T-72 tanks, 71 BMP-1 and BMP-2 IFVs, about 120 APCs, and up to 240 of a barrel and rocket artillery [2]. AD suffered some losses in 2008 and its most serious component remains 1-2 BUK-M1 AD system battalions. Of the latest deliveries, the American Javelin anti-tank missile systems and French Mistral ATLAS short-range air defense systems are of particular interest. These are insufficient not only for the war against a limited Russian group but also for the confrontation with Armenia or Azerbaijan.

Nagorno-Karabakh: Armenia and Azerbaijan Ready for War?

The Azerbaijani-Karabakh conflict is rather unpredictable. The April war of 2016 proved that as well as constantly confirms the ongoing arms race between Armenia, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR) and Azerbaijan. One should note that in 2007-2014, Azerbaijan has significantly increased its military potential by investing huge funds in purchasing military equipment in Russia, Israel, Belarus, Ukraine, Turkey, etc. The peak of Baku's military spending was in 2013 when about $3.7 billion was allocated for defense. It was seven times more than the Armenian defense budget. However, the oil price decrease and the 2015 economic crisis devalued the Azerbaijani currency more than twice, significantly reducing the military budget. In 2015-2018, Baku's defense spending amounted to no more than $1.7 billion (including the border service, internal troops, national security funding, etc.). In 2019, the Armenian military budget will be equal to $647 million (the entire amount going to the armed forces) opposed to about $1.8 billion from Azerbaijan. Also, we should not forget about NKR defense budget which is approximately $100 million.

Table. Comparison of the armed forces of the South Caucasus countries

*It is necessary to consider the close deployment of many units of the 58th Army, which can very quickly strengthen the Russian forces in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. This can include the Iskander-M tactical missiles and the massive sorties of combat aircraft.

The real balance is not so obvious. According to our estimates, these days Azerbaijan has at least 800 units of barrel artillery and 120-mm mortars, 196 107mm and 122mm MLRS units, 61 units of heavy 300-mm MLRS, about 476 tanks (including 100 modern T-90 tanks, the rest are T-72), 386 IFVs (including 118 BMP-3), and more than 800 APCs (including 230 BTR-82A). Moreover, Azerbaijan has acquired high-precision Israeli LORA tactical missile systems with at least 250 km range and SOM-1B Turkish cruise missiles. As for combat aircraft, there are up to 49 Su-25 attack aircraft, 16 MiG-29 fighters, 24 Mi-35M, and 26 Mi-24 attack helicopters. The most serious AD systems are the Russian S-300PMU-2 (two battalions), Israeli Barak-8 (one battalion) and Belarusian Buk-MB (four battalions). One should note the Azerbaijani acquisition of almost the entire line of Israeli UAVs, from small intelligence ones to the largest MALE-class. The Azerbaijani army is about 70,000 personnel [3].

Due to the lack of reliable official data and a large number of unofficial Russian equipment supplies from storage in the past, it is much more difficult to accurately estimate the number of weapons in the Armenian armed forces and the NKR defense army. The number of the first is estimated at 45,000 personnel, and about 18000-20,000 more serve in Nagorno-Karabakh [4]. The division of these two armed forces is very hypothetical as it is a de facto single system. According to available estimates, the two Armenian armies are equipped with about 400 T-72 tanks, up to 400 BMP-1 and BMP-2 IFVs, up to 480 APCs, about 600 pieces of barrel artillery and 120-mm mortars, up to 84 122-mm Grad MLRS, up to 12 300-mm Smerch MLRS and four Chinese 273-mm WM-80 MLRS. The most impressive part of the Armenian armed forces is tactical missile units, armed with at least one Iskander-E battery, eight R-17 SCUD-B launchers, and at least four Tochka-U launchers. Combat aviation is still poorly developed and is represented by 14 Su-25 attack aircraft and up to 24 Mi-24 attack helicopters. At the end of 2019 or beginning of 2020, supplying of the first four modern multi-purpose Su-30SM fighters is expected. In the future, their number will be equal to a squadron of 12 aircraft. One should note that Armenia does not buy unmanned aircraft abroad and fully relies on its battlefield-proven development. Of the available AD systems, the presence of five S-300PS and S-300PT-1 battalions, as well as the most modern Russian Verba MANPADS, is worth mentioning.

Therefore, the parties` purchase trend of long-range and high-precision weapons is clear. The above mentioned Iskander-E system, SCUD-B, LORA, SOM-1B, etc. allow hitting targets in both countries. We can also note the superiority of the Azerbaijani side in heavy MLRSs. These factors give a serious advantage to the side that will be able to cause an unexpected massive missile and artillery attack, while the enemy’s equipment is in static locations. This trend destabilizes the situation, making war more likely to happen. On the other hand, Azerbaijan's real numerical superiority is not so great, and given the Armenian powerful layered defense system, it is almost impossible to carry out a successful and rapid offensive. This was proven by the April war of 2016, in which Azerbaijan did not achieve real success, having lost up to 300-400 personnel in four days [5].

Also, we should consider the 102nd Russian military base located in the Armenian city of Gyumri, as well as the 3624th aviation base located at the airfield of Erebuni near Yerevan. According to various data, the number of personnel varies from 3,300 to 4,000 people, the arsenal includes mostly non-modernized Soviet military equipment - about 74 T-72 tanks, 80 BMP-1 and 80 BMP-2, at least 12 self-propelled artillery units 2S1 Gvozdika, at least 12 Grad MLRS, at least 2 Smerch MRLS, 2 batteries of S-300V SAM, one battalion of Buk-M1-2 SAM, 18 MiG-29 fighters, 8 Mi-24 helicopters etc. [31-32]. First of all, these forces guarantee non-interference of third countries (primarily Turkey) in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict escalation. That gives Armenia the opportunity to fully concentrate all its forces in the Azerbaijani direction. Participation of the 102nd base in the conflict is possible in the conditions of a direct invasion in Armenia.

Despite recent external pressure on Armenia and Azerbaijan, the negotiation process has hardly broken the deadlock. The new Armenian leader, Nikol Pashinyan, was received quite optimistically. However, even open pressure by US President's National Security Adviser John Bolton lead nowhere when he tried to quickly resolve the conflict with subsequent participation in the blockade of Iran. On the contrary, the parties` position soured, which only deteriorated the situation. A full-scale war between Armenia, NKR, and Azerbaijan can be destructive, and the involvement of other players: Russia, as the 102nd Russian military base is located on the territory of Armenia, Turkey (Azerbaijan's closest ally and a NATO member) and Iran, can provide a large regional conflict with unknown results. Small flashpoints, like it was in 2016, are unable to solve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Being the major destabilizing factor in the South Caucasus, the conflict will be a long-lasting one as is proven by the above-mentioned facts. Until the time Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is resolved peacefully, there will always be a threat (albeit a very small one) of a large-scale regional war.

***

Comparing the two, at first glance, similar situations — the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the conflicts of Georgia with Abkhazia and South Ossetia we can see a huge difference in both political and military dispositions. In the first case, we are talking about the opposition of the parties located in approximately the same "weight class", moreover, under the scenario of hostilities limited to the territories of Nagorno-Karabakh (without involving Armenia), direct participation of Russia in the war is practically excluded. The economic and demographic advantage of Azerbaijan, besides a significant gap in the equipment and strength of the armed forces of the parties, creates certain risks of conflict escalation. This is confirmed by the April war in 2016. Separately, it should be noted that the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic is not recognized by Armenia, and since 1994 there have been unsuccessful negotiations between Yerevan and Baku, which have intensified after the Armenian “velvet revolution”. However, the temporary lull on the border, which was established for a few months, unfortunately, is coming to an end — the sniper war again went into action, 60-mm mortars were also used.

As for the Georgian-Abkhaz and Georgian-Ossetian conflicts, the security of the Russian-recognized new republics — Abkhazia and South Ossetia, is almost completely ensured by the Russian troops. Even the forces of the 7th and 4th military bases, without the involvement of additional troops, are sufficient to reliably freeze the conflict, and the current Georgian leadership does not harbor unnecessary illusions and is not investing too many resources in modernizing the armed forces. Nevertheless, even the most frozen conflict in certain conditions can go along the path of escalation. In the case of Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, this can happen only with very large regional shocks: such hypothetical and unlikely scenarios as destabilization in the Russian North Caucasus, the war of Russia and Turkey, etc. Another defrosting mechanism can be a regional war, which arose initially due to the escalation in Nagorno-Karabakh — Turkey, Russia and, less likely, Iran may be involved into a full-scale war of Armenia and Azerbaijan. This may also involve Georgia in these catastrophic processes. In this sense, the key to peace in the South Caucasus lies in Nagorno-Karabakh. The settlement or at least a deep freeze of this conflict can mitigate most of the regional military risks.

1. Military Balance 2018. IISS. 2018. p. 187

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. В ожидании бури: Южный Кавказ / М.С. Барабанов, М. Йешильташ, А.В. Лавров, Л.А. Нерсисян и др.; под ред. К.В. Макиенко. — М.: Центр анализа стратегий и технологий, 2018. — стр. 161