Russia and China have a truly unique role in the international arena, which makes their relations a huge and very complex topic. Neither country accepts subordination to anyone or to each other. China is unable to be a junior partner, and the same goes for Russia. Fyodor Lukyanov sat down with RIAC to describe the future of Russia–China engagement in the emerging world order.

Good afternoon, Fyodor Alexandrovich. Thank you very much for agreeing to an interview as we approach the 9th RIAC and CASS International Conference Russia and China: Cooperation in a New Era. As the Editor-in-Chief of Russia in Global Affairs, one of Russia’s leading journals on international relations and the media partner of the event, and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Foreign and Defense Policy Council (SVOP) and Academic Director at the Valdai Discussion Club, you have a keen eye for trends in Russian and global politics, in expertise and in the academic community. Do you feel the presence of that very “pivot to the East” that is talked so much about? When, in your opinion, has this process started?

Yes, it’s quite there. It started around the same time as the idea of a “pivot to the East” was officially announced, i.e. in the early 2010s, and intensified after the start of the special military operation. Another question is more complicated: what does this “pivot to the East” exactly imply? We cannot say that we lack or have ever lacked an orientalist school. On the contrary, it was strong in the Russian Empire, in the Soviet Union, and in the Russian Federation. True, after the USSR collapsed and the main thrust in international activity had changed, the Oriental direction seemed to have been sidelined.

Now, this impression has vanished into thin air, fortunately, and, I think, irrevocably. However, amid the declining interest in the West, certain distortions of orientalist knowledge have come to light. We have brilliant Sinologists, but in the international environment that has emerged, and first of all in the economic sphere, we need a significant number of professionals who understand the specifics of the Chinese economy and the proper approach to doing business with Chinese partners rather than China’s ancient philosophy or subtle nuances of the Chinese language. This is probably a scarce commodity today, and the shortage will become even more apparent as Russia and China deepen their ties.

In general, the ability to communicate with partners from non-Western cultures in a proper way seems the key competence to me that needs to be developed. The paradox is that even though we do not communicate with unfriendly countries today, we understand them well. We are not happy about it, but we are used to dealing with them even in a state of conflict—I’d even argue that especially in times of a conflict. There is no conflict with the East today; moreover, there is mutual interest and often mutual sympathy. Yet this sympathy is not always based on knowledge. Even if there is some knowledge, it has not yet translated into an array of skills necessary for comprehensive development and maintenance of our relations, no way.

Accordingly, the “pivot to the East” has taken place, but after that it’s difficult for us to move forward. Yet demand begets supply, so I think we’ll cope with this challenge. We have no other options but to move in this direction during the next few years or even decades.

You have forestalled my next question. Given the growing urgency of establishing Russian-Chinese partnership at all levels, it seems that everyone should become at least a bit of a Sinologist today, whereas many of us have learnt European languages. What, in your opinion, is the particular difficulty for such specialists in building communications with China? How should we answer to this challenge?

It’s a good hypothesis that everyone should become a bit of a Sinologist. But no, they shouldn’t. Of course, it would be great if many people started learning Chinese, but you have to look at things realistically—it’s a long and complicated process.

In my opinion, the problem is broader than that. We know very little about the history and culture of the vast region to which we belong. I mean Eurasia, of which Russia has always been an integral part. Within this huge continent Russia evolved and developed alongside its neighbors. East and Central Asia, South Asia are no less important for us historically than West Asia (Middle East) and Europe. But at least we all know the history of the latter, simply by virtue of the school background and traditions, while only people keen on Eurasia in its entirety know the history of its other nations.

This does not mean that we should not study Western Europe or the United States, but in terms of cultural and historical roots, the Eurasian heritage is more important to us. It is necessary to realize that we are part of that world, we do not yet have this awareness. Because regardless of how many times we repeat that we are “Eurasia,” we will not become Eurasians until our angle of view shifts. Again, we are not talking about closing the “window to Europe” and opening something else instead; we are talking about correcting the imbalance, and therefore, about a more adequate view of ourselves.

For this to happen, we don’t have to become “a bit of a Sinologist”. It will be enough to realize that we are a part of this huge continent, which includes cultures that are not ours, but are related to us, as we are interacting with them today. It has nothing to do with conflict. Even if there were no conflict with the West, the world is changing in such a way that our belonging to this part of the world would have to be restored. For now, we have to restore it in a specific environment, and it will take time.

If we talk about China, the problem is not in learning Chinese. We will probably come to the point where its spread, including in schools, will be growing rather quickly. But do we see many exhibitions of Chinese art or many screenings of Chinese movies? No. It is impossible to impose this cultural paradigm since we are used to something else. But it is possible to expand our horizon. This will also take some effort, but if we exert ourselves, everything else related to business and security in Russian-Chinese relations will be perceived differently. And now it seems that we have turned to the East, but our collective subconscious is still dominated by the idea that “we do not actually belong there,” so we just have to look eastwards a bit more.

Then let’s talk a bit more about mass culture and political culture in our dialogue with China. The PRC is now actively shaping its new foreign policy doctrine. In the 10 years since the concept of the community of mankind’s common destiny was put forward, three global initiatives have emerged. But from the outside it may seem that, compared to Western doctrinal documents, they are empty in content. There are a lot of beautiful words and phrases, but it is not quite clear how to put them into practice. In your opinion, why is this so? Is it because we still do not understand how Chinese culture works? Or is it because China is only at an early stage of shaping its own vision of the future world order?

It’s both. China is surely at an early stage of—if not quite forming its own view of the world order—formalizing it in a way that would be understandable not only to specialists. They have the same problems as we do, only in reverse. We need to learn to understand them, and they need to learn how to formulate their vision in a way that would be easier to understand globally.

So far, the feeling that we are waiting for specifics and China is offering something vague leads to the suspicion that they are messing with our minds. In this sense, a comparative analysis of Western and non-Western views of international relations will be crucial in the decade to come.

The Western view of development assumes that it occurs through conflict. It is not always possible to resolve contradictions amicably, and so it comes down to crisis. Accordingly, crisis, even if it causes significant damage, is necessary and indispensable, because the parties break out of the erstwhile contradictions through it and start moving towards something new. Hence, for example, Joseph Schumpeter’s famous concept of “creative destruction”—the destruction of the old to create the new. The Chinese paradigm, if I understand it correctly, is the opposite. Conflict is unnecessary. It does happen, but it does not bring any good things. So, it should be avoided in general. Hence the narrative about harmony, common destiny, and suchlike.

For several centuries, the West had the upper hand, so the Chinese principle simply lost out due to China’s lesser military and economic potential. But the balance of power has now shifted, and it is no longer possible to ignore China and its approach, whether we consider it sincere or not.

The Western approach to development is exhausted not only because the West is no longer the strongest. Just as importantly, the world has become so complex that conflicts can no longer address the entire range of problems. Previously, clashes led to the establishment of a new hierarchy and new rules, but now there is no such linearity. Hierarchy is not established, and although some contradictions are removed, others are added.

And here, I guess, is the fundamental reason why Russia should strive to deepen its understanding of China. If we realize that Chinese formulas are not just fantasy or demagoguery, but offer a different methodology for solving development problems, not only will rapprochement with China intensify, but our own understanding of the world we need and should strive for will take shape.

The phenomenon of our country is that peace (rather than war) suits us perfectly. Russia, by and large, needs nothing. It has everything and cannot be bypassed, as the events of the past two and a half years have once again confirmed. Therefore, understanding the Chinese view of the world is important not just to find common language and ground with the Chinese. This task is understandable, but it is not the main one. Understanding the Chinese view is the key to being able to look differently at one’s place in the world and what kind of the world is preferable to us.

Of the ideas that Russia is articulating today in relation to the rest of the world, which ones seem to you the most creative and viable?

None. And it’s not that our ideas are bad or good. We have different ideas. However, there is no demand for other people’s ideas today. We ourselves, and quite rightly, have been saying for a long time that the world is becoming multipolar and more diverse. Everyone is trying to rely on their own cultural tradition. The same is true for the West as well, as a matter of fact, but their tradition is transforming into a more and more specific one. What is perceived by us as sheer madness—the liberal ideology taken to extremes—is in a sense how they see their tradition and identity, and it is their right. As long as they don’t impose it on others.

Therefore, the era when someone would come up with some new ideas and everyone would follow them is a thing of the past or has already sunk into oblivion. The Collective West is no longer a flagship, but a community that, by its own logic, is trying to keep itself in a consolidated state. So far quite successfully, by the way. But it is no longer a universal example or dogma for others. China is not an example for everybody either, because it is impossible to use it as a role model, due to its unique cultural specificity. Can Russia serve as an example? Does anyone want examples at all? The modern world does not need to be taught or shown how to live, but, as many put it, it is looking for best practices. What are your capabilities? What have you achieved in solving specific problems? This is what attracts attention.

There is a lot of debate about ideology in Russia right now. There is an opinion that nothing will work without ideology, especially under an acute political crisis. I am sure that if ideology is needed, it is for Russia’s internal development: for the consolidation of our society, for understanding the hierarchy of tasks. It should not have anything to do with the outside world. It cannot be extrapolated anyway, simply because everyone currently has their own ideology and value-related narrative.

Accordingly, the task of exporting ideology simply should not exist. On the contrary, the successful solution of internal problems—social, economic, political, cultural, climatic—is a powerful tool of influence in and of itself. If you are able to solve your own problems, then you have something to learn from, and if you are not able to, but go to others and say: let us put our own problems aside now and instead go fight someone else... No, thank you, they will say, we’ll do it on our own.

You mean being a notch above the rest?

You don’t have to be a notch above the rest. Again, the phrase “a notch above the rest” immediately lays down some sort of hierarchy. Being just okay. Being able to solve your own problems. Any problems.

This is very interesting and, I think, should be a topic for a separate discussion. But you’ve just said that we should simply be okay. But Russia and China set themselves the task of being in the world order. What is then needed for this to transpire? Where is this space for interaction between Moscow and Beijing in international politics?

Being okay for ourselves, being in shape—this is really necessary, regardless of everything else. Being part of the world order is quite a different matter. A very big question arises here: is this order even possible now? Again, according to the tradition in which we grew up, with the historical context in which we lived, we’ve been used to the idea that there must be some order. Those orders were normally used to be established in an extremely bloody way, starting with the monstrous Thirty Years’ War, which simply destroyed the continent, and ending with the Second World War, after which the last kind of orderliness familiar to us was introduced.

Now let’s look at the present-day situation: it seems as if the order is ending or has ended. And it is not the order that we saw emerging after the Cold War, but the order that was established after the Second World War. Because after the collapse of the Soviet Union, even though the balance of power changed, the system of international institutions headed by the UN was preserved. Today, it is crumbling as well, and we see it at every turn. Internal contradictions in the existing institutions and international regimes are insurmountable.

Accordingly, the old system is not revivable in its former shape. Traditionally, we think that there will be or should be something different. But for something different to emerge, a new hierarchy, new institutions or a system of relations must be established.

And how will it be introduced? Through war, as before? In the current environment, though, this will be a nuclear war. If not through war, how else? There are now far more indicators of influence than ever before, and the number of players or actors who have an impact on the world situation is incomparable to what we had earlier. There are dozens of them, and each one affects the environment in its own way. Sometimes it turns out that a medium-sized power is more effective and more influential than a great power because it is more flexible and compact. How can a world order be established in this situation?

The most popular idea is multipolarity. But multipolarity is not an order. Multipolarity is a certain reality. Moreover, the theoretical literature is increasingly questioning the relevance of poles as an analytical category. A pole is something that others are drawn to. And recognize. And what if others refuse to be ‘attracted’ to a particular pole? The idea of a pole was invented in America in the 1970s, but today the situation has changed.

Under these circumstances, the advantage of Russia and China is that our two nations are indispensable and necessary links in international relations, as the history of the previous 200 years has proved. Both China and Russia experienced monstrous cataclysms during this period, but it was impossible to ignore them, regardless of what the order looked like. And this, it seems to me, is what unites us: nothing will ever happen without us.

Therefore, relations between China and Russia, including in the international arena, are a separate, huge, crucial and very complex topic, because neither country, as historical practice has again shown, accepts subordination to anyone or to each other. The experience of the “great friendship” between the Soviet Union and China has shown that China will not concede to being or willing to be a junior partner. The same applies to Russia. I guess it is the realization of the absolutely unique role of both countries on the world stage that prompts the kind of joint work we are witnessing, the attempts to formulate what kind of relationship Russia and China really have.

The formula that Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping reiterated, notably that the relationship between the two nations is deeper and closer than an alliance, may be artificially contrived, but it is very adequate and successful. It shows that there will be no alliance, as it implies self-restraint for the sake of the other side. But our understanding of the importance of bilateral ties is not going anywhere. Relations may change and transform, no one is doomed to a radiant future, but, in my opinion, we can expect—with a high degree of confidence—that there will be no major conflict between Russia and China. The current contradictions related to the incomplete coincidence of interests are a given, but this is the way it should be.

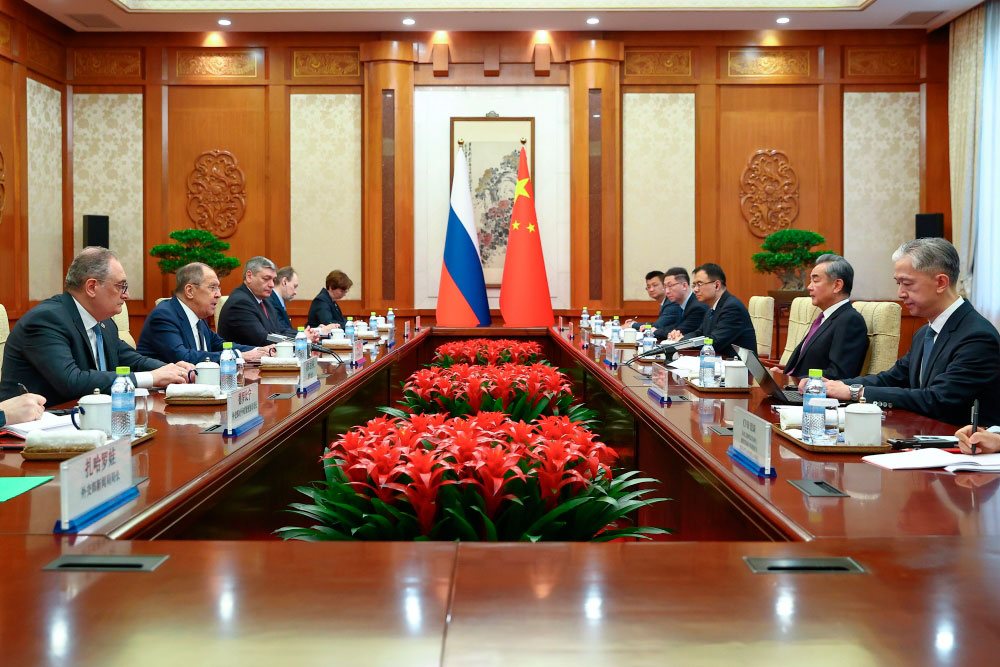

Do you see Vladimir Putin’s visit to China as successful in building a future in which the risk of conflict between the two sides is minimized?

Yes, it seems successful to me, but with the understanding that in the system of Russian-Chinese relations, success is not a result, but a process. We will never have a formalized alliance with China. It will not be the case that everything has been decided and a bargain has been stricken. Instead, it will be a process of cultivating our relations, addressing problems in the best way possible, and coordinating efforts where our tasks overlap.

The situation is now extremely complex and non-linear. First, China proceeds from its own interests and maneuvers in building economic ties with Russia and other players. But it would be strange to reproach China for this maneuvering, because every country surely promotes its own interests, and this is normal. Second, two large and complex countries like ours cannot solve all the problems in one fell swoop. But the process of searching for mutually acceptable measures is ongoing, and the visit reflected this effort. It is symbolic that Xi Jinping paid his first visit as President of China to Moscow in 2023, and Vladimir Putin paid his first visit, as a newly elected President, to Beijing a year later.

Will it always be like this? I don’t know. But this is clear evidence of the structural complementarity of our nations. Not in the primitive understanding of complementarity, that we have oil and they have something else; and it would be good to correct this imbalance, by the way. Here, I’m more referring to the structural complementarity as the basis of global stability. In my opinion, this will remain the case.

Great, thank you. Then, perhaps, we should conclude our conversation where we started. What can we, the expert community, do to contribute to this process? What topics can be prioritized at a future RIAC and CASS conference, what should attract our attention?

As an expert community, we should probably do the same thing we do in addressing other issues. We must avoid exaltation—which, unfortunately, for quite understandable human reasons—is present in the atmosphere we live in. It is very difficult to keep cool, but that’s the top priority. Then, as we mentioned when we started our conversation, not everyone will become a Sinologist. If someone succeeds in learning Chinese, it’s wonderful, but this is not an end in itself. But to understand that the world is huge, that there are two hemispheres—both vertically and horizontally—and that power confrontation is limited in terms of its potential, is the most important thing, to be honest.

Thank you very much, Fyodor Aleksandrovich.